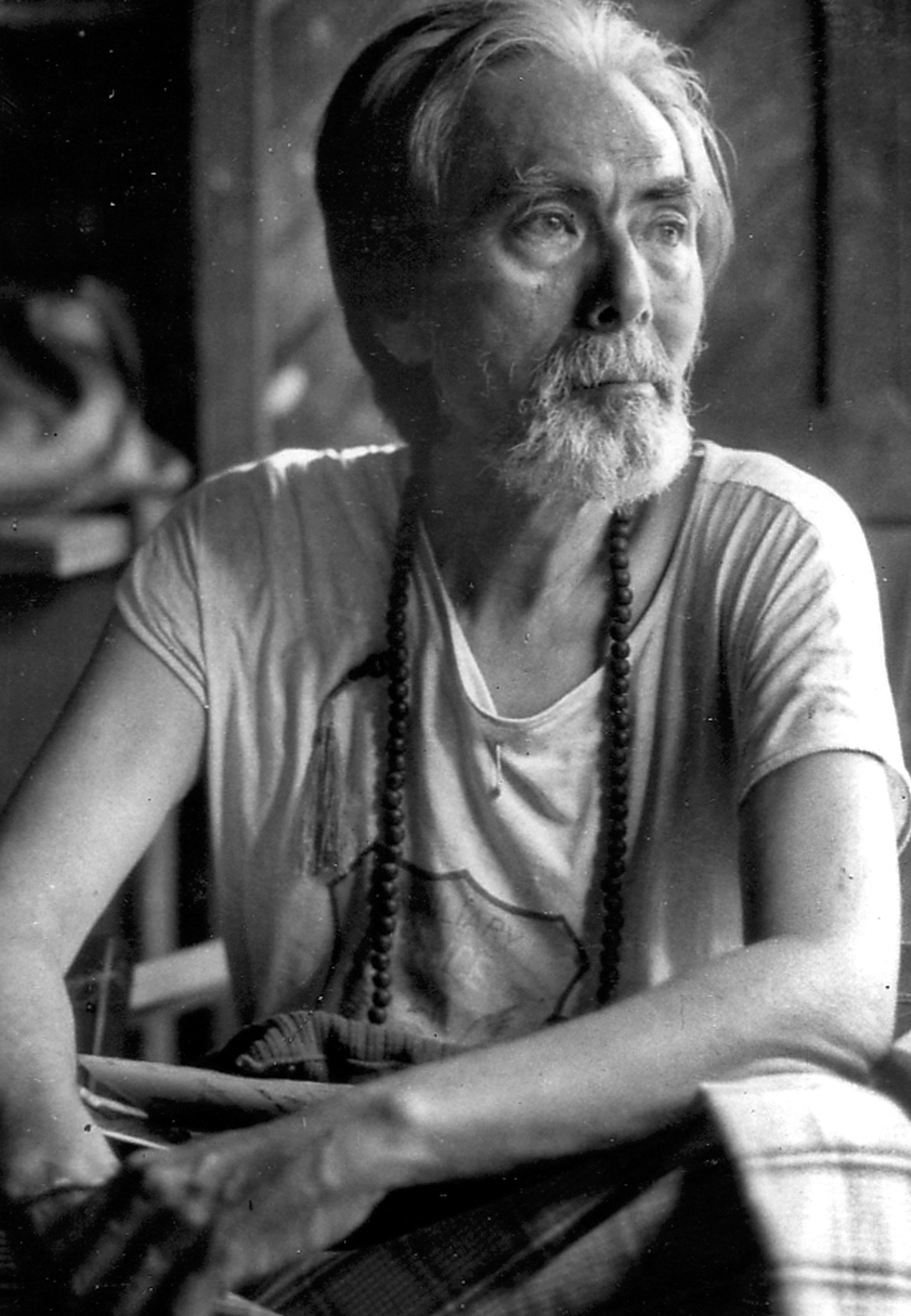

Bagyi Aung Soe:

Art Hereafter

by Grace Hong

Art Hereafter

by Grace Hong

“Art is what flows through the soul of the people, where the old and the new meet. We cannot destroy all that is old, or accept all that is new. Nature will choose the good traditions out of the old, sincerity and truth out of the new. Not everything old is decadent, not everything new is revolutionary. We have to search for the soul in the old, and foster the progress of the new. [...] We must sow the seeds of modem art, to weed, to fertilise; this is the artist’s responsibility towards the people.”

– Bagyi Aung Soe (1978)

For someone known as the trailblazer of Burmese modern art, the life and practice of Bagyi Aung Soe (b. 1923–d. 1990) escapes easy definition. His pursuit of modernism beyond Western schools of thought was mired within an individualistic expression in conversation with religious, sexual, and political themes. Aung Soe relished illustrating with felt-tip pens on scrap paper over oil paintings on canvas; his works were found in magazines and not gallery walls; he was fiercely independent and likened being compared to Picasso as “the worst insult.”

In 1924, Bagyi Aung Soe was born to a wealthy family in Burma (now Myanmar) under colonial rule. A bildungsroman of the artist could parallel the growth of nationalist sentiment in the country, with his illustrations first appearing in Taya [Star] magazine in 1947—a publication founded by Burma's unofficial poet laureate, Dagon Taya, who advocated for the country’s independence—on the eve of Burma’s emancipation the following year. At the age of 27, Aung Soe received the Indian Government Scholarship to study at the Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan founded by Asia’s first Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore. Aung Soe’s year of education in the school under the tutelage of Nandalal Bose meant an exposure to traditional and modern Asian art forms, including Japanese ukiyo-e, Javanese batik, and modern Indian art, amongst others, as well as a friendship with his peers, like the modern Indonesian master Affandi who attended on the same scholarship. Aung Soe’s time at the school had a deep impact on his life and career henceforth, forming the “blueprint of his quest for a modern Burmese art,” as the art historian Yin Ker writes.

Upon his return to Burma, Aung Soe was actively commissioned to illustrate for literary magazines from the 1950s through the 80s. The lively publication scene reached all ladders of Burmese literati, allowing Aung Soe’s practice to transcend the challenges of a non-existent art market and patrons with deep pockets.

Unlike modern artists of the time whose resumes grew with exhibitions, awards, and significant acquisitions, Aung Soe refused associations with formal institutions. He much preferred his work everywhere but the specific spaces for art, eschewing its commodification and at times trading his illustrations for groceries. This rejection of the proper and its society, along with his penchant for dressing poorly, drinking heavily, and inability to be a successful breadwinner earned him the title of the enfant terrible. This he acknowledged readily, signing hso in many works, meaning “bad” in Burmese.

But his reputation for being untameable was part of being the alluring genius. Aung Soe also taught, wrote, and acted, furthering his image as a polymath.

Aung Soe delved in all that he knew, amalgamating a seamless blend of Western modernism and traditional Asian arts; the spirituality of Hindu-Buddhist beliefs; figuration and abstraction—all was material for “an extended form of communication” as he was taught under Nandalal. So committed was the artist that he began adding bagyi as a prefix to his signature from 1955, the word meaning painting and art in Burmese. With this addition, Aung Soe’s authorship would always be read in tandem with Burma’s art—his role as artist for its people foremost in his identity.

Toward the end of his life and as Burma’s economy dwindled, Aung Soe was in poor health and poverty. In response to the 8888 Uprising (named after 8 August 1988) that resulted in the brutal murders of thousands of students, Aung Soe’s provocative illustration for the University of Medicine I Journal effectively cemented his status as an outcast with the new military government, though his prestige amongst younger artists continued to grow. At the age of 66, Aung Soe passed away in 1990.

"“If someone calls me a Burmese Picasso, it really hurts. I would rather be hit in the face. It is like being called the second Po Sein [a famous circus monkey named after the renowned Burmese dancer Po Sein]. That is my view. Besides, there are many similarities between the West and the East. In the same way that Western culture spread across Asia, so did Asian culture in the West.”"Bagyi Aung Soe, written communication, c. 1987

The legendary story of Aung Soe continues to captivate audiences with his fecundity for the different. This year, the artist was the subject of a retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, his first major solo exhibition with over three hundred works and documents from four decades being shown. The exhibition’s curators include Catherine David, Deputy Director of the museum and Yin Ker, an Assistant Professor of Southeast Asian art at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, who has been furthering scholarship about Aung Soe for the past two decades. With the crucial role of his education at Santiniketan highlighted in the story of Aung Soe’s brilliance, the exhibition also affirms institutional interest in exploring modernisms outside of Western frameworks, signalling an inquiry that might see the definitions of modernism expand to include diverse schools of thought and the spaces of training that brought them forth. For the universalist Aung Soe who cherished artistic innovations of unique and traditional Asian art forms, one can imagine this a welcome development.