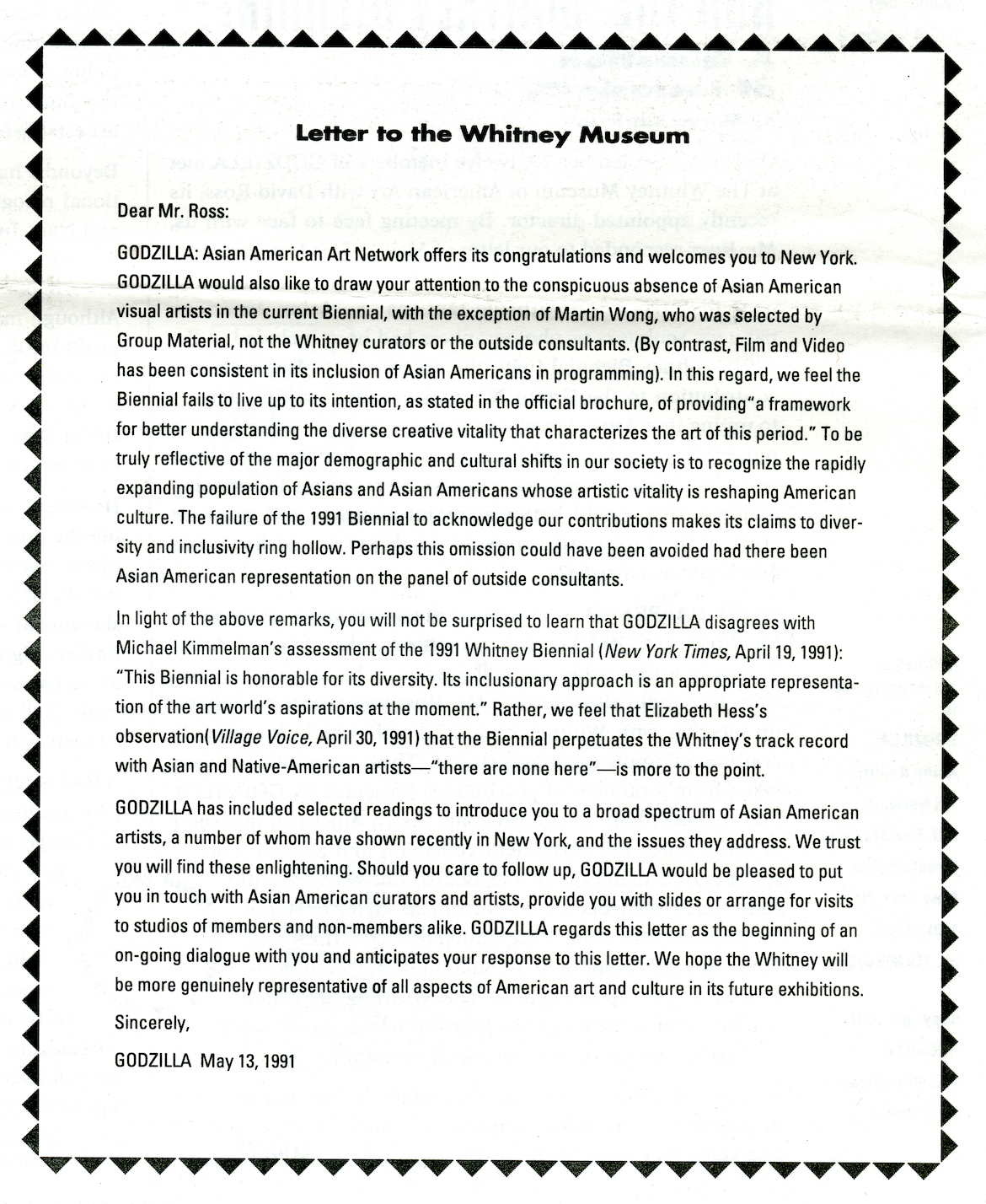

Godzilla was never an agreeable monster, though there has been great effort in recent years to tame this formidable Asia-Pacific threat. The filmic Hollywood adaptation Godzilla (2014) portrays the beast as an unorthodox ally for American militarism—a complete inverse of the 1954 Japanese original. I also often think about the single photograph that circulates as visual representation of the Asian American Art Network, Godzilla: packed shoulder to shoulder, a tight-knit group of Asian faces smiling or mid-laughter.

To see this photo today inspires the romantic notion that kinship was forged along common radical ideals, and that those transgressive energies have since miraculously gained institutional vitality. Eugenie Tsai before she was Senior Curator at the Brooklyn Museum and Byron Kim before he was art canon. Tom Finkelpearl, behind the camera, would later become Commissioner of the New York Department of Cultural Affairs. In reality, the roving organisation continues to be embroiled in disagreements, both with institutions and with each other.

The arts network reawakened for the occasion of what should have been a long overdue retrospective of their work at the Museum of Chinese in America, curated by Herb Tam and Ryan Wong. During the planning stages, however, Godzilla affiliates Tomie Arai and Arlan Huang decided to withdraw in protest of MOCA’s cooperation with the city’s new jail plan. Spearheaded by New York City mayor Bill de Blasio, the citywide plan would finally retire Rikers Island prison, but replace it with new vertical jail towers in multiple city boroughs. One of the proposed locations is in Chinatown, situated just a few blocks away from MOCA.

Expressing solidarity with local businesses and community leaders, Huang and Arai objected to the museum’s request and acceptance of over $35 million in “giveback” funds made available through the proposal.

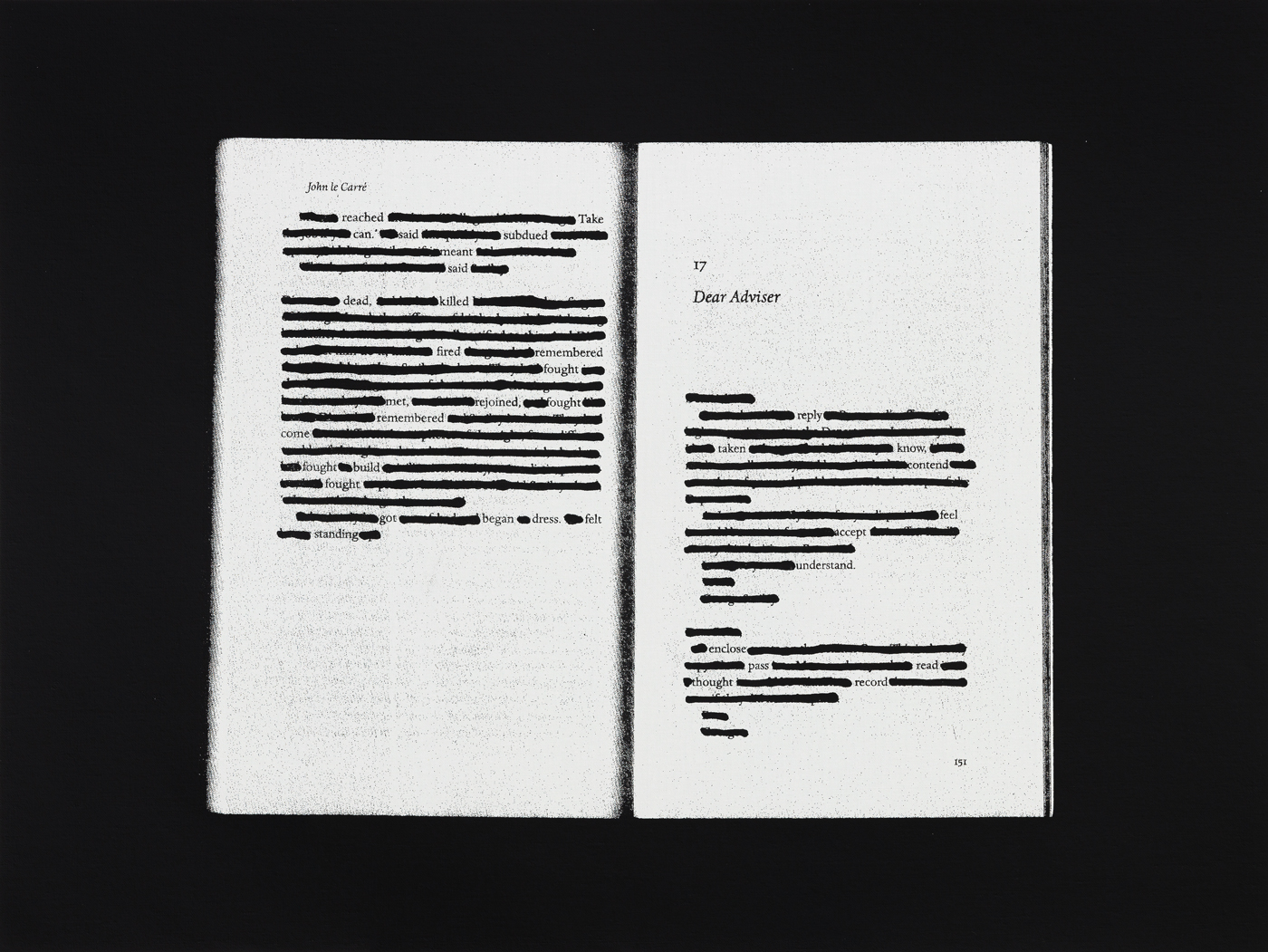

Over the course of this past year, other Godzilla members gradually followed suit in negotiating with MOCA to oppose the jail plan and host an open forum. When the museum refused, 19 Godzilla members (from the total 23 included in the exhibition) ultimately withdrew this past March. Identifying themselves as G19, the group notified the museum of their decision in an open letter published on e-flux that read: “The complicity of MOCA’s leadership with the jail plan amounts to supporting the system of mass incarceration and policing that disproportionately affects Black and Brown lives.” Whether this gesture has done anything to move the city government’s commitment to its prison expansion plan has yet to be determined.

Although many have written in general indignation towards the immorality of the circumstances, there seems to be little regard, even from the museum, for the price that Godzilla has paid for its activism. As an Asian American in the arts, albeit from a younger generation, I can guess how it feels vain to even address the pain of turning down an opportunity for celebratory recognition. For even if one were to survive the art world’s casual racism and exoticism (at times confused for appreciation), the centuries of work done to keep Asians at bay in the United States leaves a representational void that can feel debilitating and lonely.

Art critic Dawn Chan remarked as recent as 2016, “I leave most art shows still looking for my own face in the present.” Godzilla offers not only the solid ground of an identity that was real but also a semblance of familial roots— togetherness embodied.

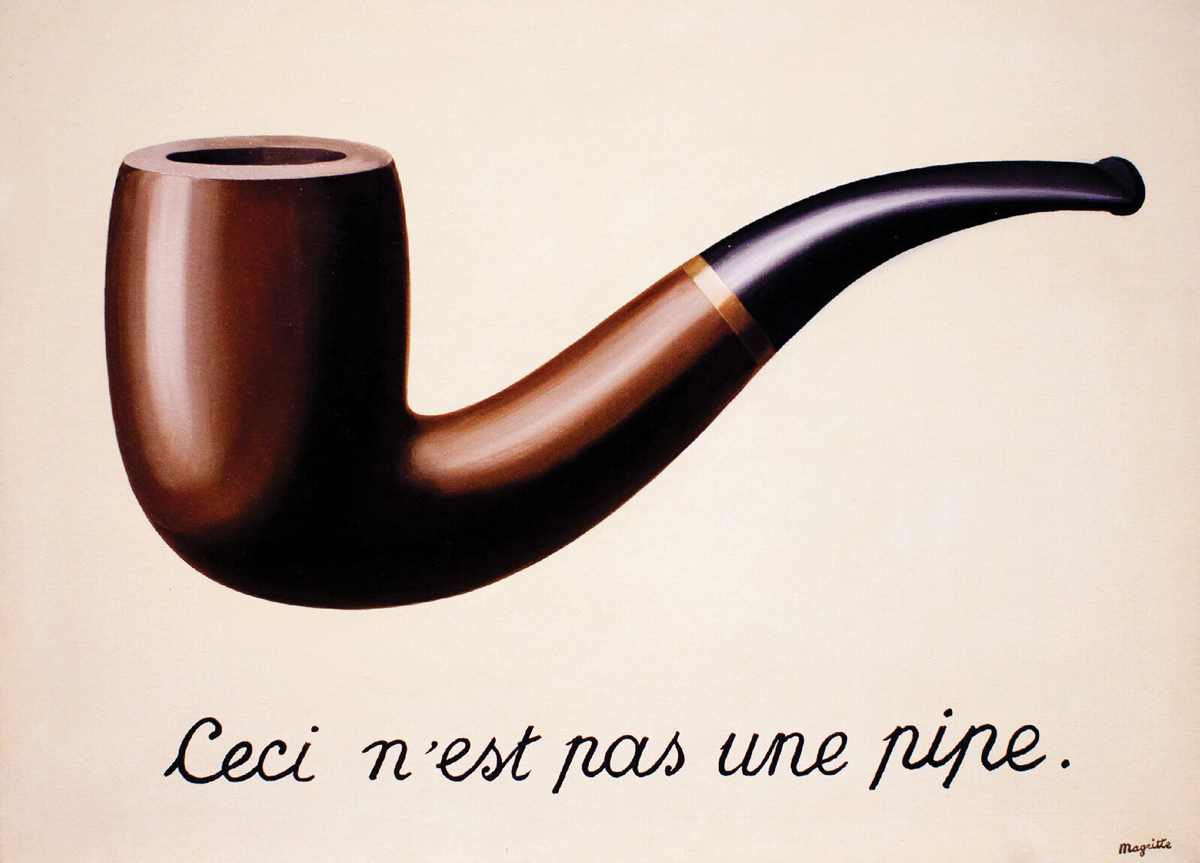

Between the glamorised model minority and gruesome negative stereotypes, there remain very few options for Asians to be legible in this country. Responding to #StopAsianHate, in an interview with CBS News, scholar Anne Anlin Cheng reminded us of the human stakes when we fail to abate even minor offenses: “Mild forms of racist, sexist harassment is on a continuum of what we saw in Atlanta last week, a very lethal expression of that.” Without knowing a history of artists who have tried to correct this course, Asian American visual culture seems relegated to a perpetual orbit where different generations will posit the same questions for the first time.

Godzilla provided a utopian vision of pan-Asian unity that, during its short lifetime from 1990 to around 2001, lived on ascetic principles like eschewing institutionalisation or corporate funding structures, as well as creating spaces away from the institution to feel validated. When Vincent Chin was murdered by white supremacists, Godzilla members participated in public art projects to mourn his death. In 1993, they staged a group exhibition at Artists Space titled A New World Order III: The Curio Shop, which challenged the white cube. Although the group varied vastly in artistic style and personal backgrounds, they shared a common pursuit and inextricable link to activist inclinations.

Responding to a long history of invisibility and racist depiction, Godzilla’s work in part seemed to be issuing a remedy through more authentic representation. Members Ken Chu and Bing Lee even dreamed of one day opening an Asian American museum; a “place of our own.”

When I heard that MOCA would be the first museum to present an exhibition on Godzilla’s work, an Asian American identity that was “for us, by us" seemed to have a light on the horizon. However, the developing impasse between MOCA and Godzilla reveals something about the contradictions that afflict Asian American representation. For the members of Godzilla’s G19, protecting their community and keeping their values intact paradoxically entails refusing an opportunity in line with their aspirations.

Meanwhile, MOCA has felt unable to refuse favours from the carceral state; notably, the institution has only received generous government funding when it agrees to be a line item that dresses up a jail plan, or when it experiences significant damage (a devastating fire in 2020 led to $80 million from the city). The competition between perpetual foreigner versus lawful citizen is a losing game. As scholars from Lisa Lowe to Candice Chuh have posited, Asian American critique remains at odds with being inducted as American at all.

What is the political half-life of images? I think of what an exhibition about Godzilla would have looked like, had the group conceded. The photograph of friends during happier times would surely be included; a relic of a bygone time. The 19 members of Godzilla who declined to be in concert with jail profiteering instead offered a new occasion to gather: #NoNewJails. As prison abolitionist Angela Davis argues, “basing the identity on politics rather than politics on identity” remains most exciting potential for disparate strangers to unite.