Modern Matters

by Lesley Chee

by Lesley Chee

“Simplicity is about subtracting the obvious and adding the meaningful,” John Maeda defines in his book, The Laws of Simplicity, putting into concrete form one of the most significant tenets of our time. What does it truly mean to imbue our lives with meaning? How do we participate in shaping our cultural architecture? There are no longer singular answers to these questions, although we already see the start of a seismic shift in our cultural consciousness—particularly, in our lifestyle and consumption choices within the luxury domain.

Two things point to this shift: firstly, luxury clearly isn’t what it used to be, and perhaps this accounts for the loss of its sheen. More than just its final product, luxury used to be a lifestyle, one that denoted a history of tradition, superior quality, and offered a pampered buying experience, as journalist Dana Thomas writes in Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Lustre. “Gone are the family-owned businesses dedicated to integrity and quality,” she says. “The industry is now run by multi-billion dollar global corporations focused on growth, visibility, brand-awareness, advertising, and above all, profits.” There is perhaps a growing disdain against this; a rage-against-the-machine sentiment, if you will, that goes far beyond the bureaucracy of our governments, glossy Wall Street façades, and the minority 1%. The rebellion of our time is perhaps not so much about making consumption choices that define who we are, but more about turning our backs on a pervasive corporate agenda.

This leads to the second factor of change—how we’ve come to perceive brands, and, by association, ourselves.

At the height of luxury, some brands were hallowed names, equated with certain standards of quality, exclusivity, and elitism—a rarefied club of sorts that only a select few had access to. Fast forward to today’s burgeoning mass-luxury market, where these very standards are being put to the test; brands now realize that it is imperative for them to build equity, and what they stand for, beyond just their names. Luxury brands face some pertinent questions: what do people associate with your brand? How loyal are people to your brand? What story does your brand tell?

That story is at danger of being diluted when brands become ubiquitous, as has Louis Vuitton, which a billionaire woman described as “too ordinary” to China Market Research Group Managing Director Shaun Rein in 2011, in a Business Insider article. “Everyone has it,” she said. “You see it in every restaurant in Beijing.” When Louis Vuitton no longer has control or say over who owns their products—as once was in the distant past—they find themselves with an identity crisis. Asked to rate the reasons for their luxury purchases on a scale of one to five (with higher scores indicating greater agreement), respondents in a China Confidential survey gave a 3.92 rating to “expressing my personal tastes”. The outlook seems to be: I earn enough to own a Louis Vuitton bag, as opposed to: I own a Louis Vuitton bag because I believe in the brand. For high income Chinese, this is an outlook that has become particularly polarising; just 12.9% of those with annual household incomes in excess of RMB350,000 (S$75,000) purchased Louis Vuitton products when they travelled overseas, compared with 24.3% a year earlier. Coupled with China’s aggressive anti-corruption campaign, and the fact that Louis Vuitton’s heavily monogrammed goods are among some of the most extensively replicated luxury goods in the world, these findings are disquieting, and indicative of a shift not just at Louis Vuitton, but in the luxury market as a whole.

It seems that the brands or products that will best survive this shift are those that aren’t full-frontal luxury. In this world oversaturated with logos and ads, the success of some brands will rely on their ability to adapt and stand out. This involves “taking themselves out of the clutter and noise...and whispering in our ears to be heard above the roar of the mediascape,” Faith Popcorn of Faith Popcorn’s Brainreserve says. Classic items will fare the best, she adds, because of the equity that has been built up around the product, and the fact that they don’t have to yell to be heard, seen, or appreciated.

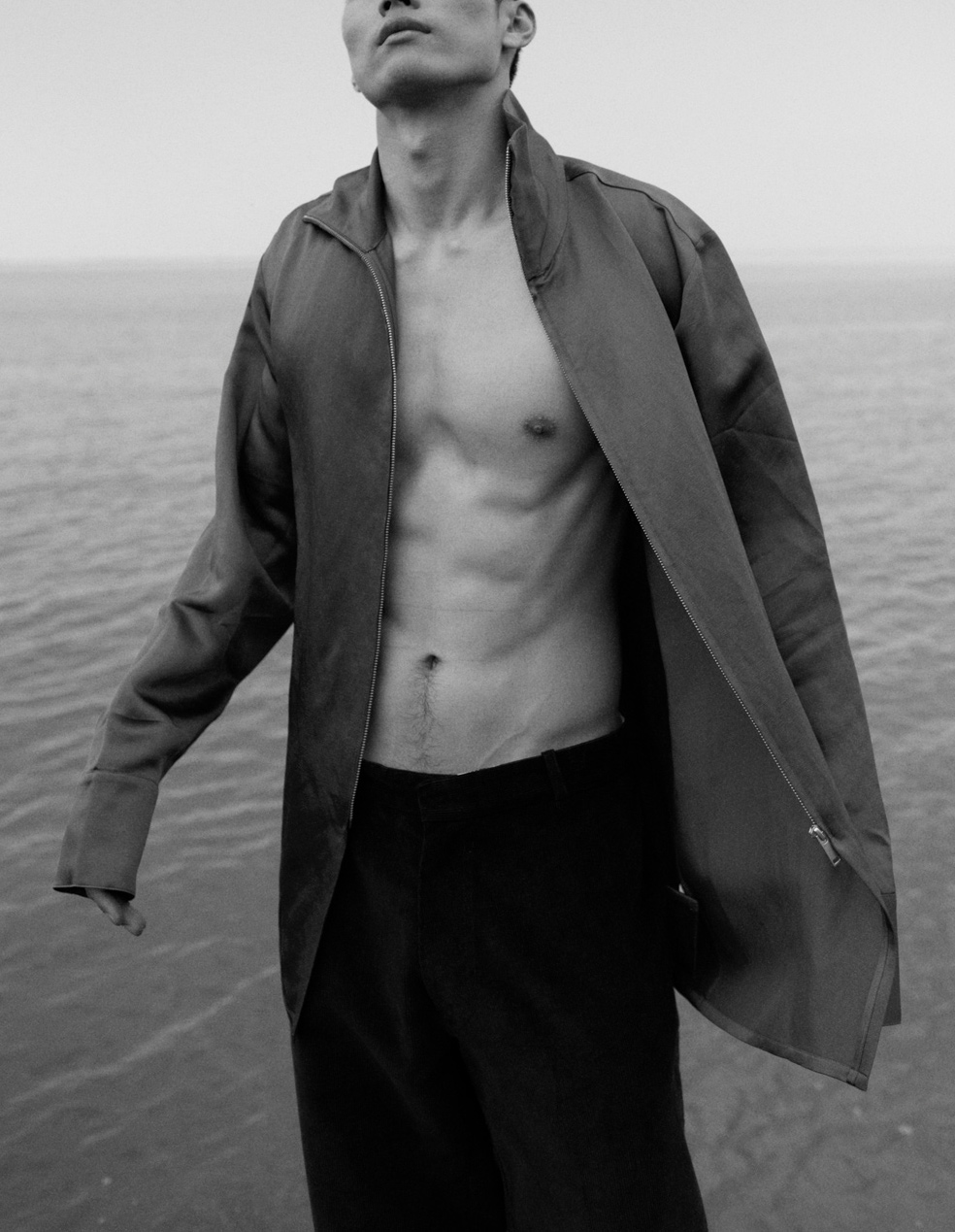

Céline, Bottega Venetta, and The Row are some clear-cut examples of brands that are discreet, low-key, and synonymous with stealth wealth. Eschewing logos and extraneous add-ons on garments and accessories in favour of a decidedly minimalist aesthetic, these brands capture the emerging zeitgeist of our time. The industry is beginning to understand that while many of us love and appreciate beautiful things, we no longer want to parade our wealth and status in a world of such inequality.

In embracing subtlety and applying the simpler values of yesteryear to a technological age, we are slowly but surely stepping off the frantic treadmill of high-turnover consumerism. Simply by doing, desiring, and accumulating less, we are making a powerful enough statement with the statements we are not making.

In this reaction to fast, disposable fashion, consumers are now pursuing products out of a genuine interest in their origins and make, opting to invest in pieces with mileage, and that aren't run-of-the-mill—arguably, what some high fashion brands are in danger of becoming. There is a desire for unique experiences, rather than just the final product: something that is personal and individual, that cannot be easily replicated. Here is where bespoke, custom-made, and handcrafted goods and products have an edge—items that feel like they have some story behind them, a story that the buyer feels they can relate to and also relate to their friends. The value and richness of these products are intrinsically tied to the storytelling; consumers are more likely to pay a higher price for quality and the knowledge that what they’re getting is unique, not mass-produced and commonplace. We take these stories and make the products our own—the pair of brogues handmade by a family-run shoemaker in Italy, for example, or the bespoke suit crafted in a hole-in-the-wall underground store in Tokyo—because it feels like this is the only way we can feel a reconnection to the proliferation of sometimes faceless and anonymous mass of clothes, bags, shoes, jewellery, and accessories that we all own.

At present, the meaning of luxury has changed: it is no longer about owning something for the sake of status and elitism; it is no longer entirely relegated to material, tangible things. Real luxury is in being able to appreciate the finer things in life, of having the ability to buy a story and an experience instead of just a purely functional product, and in having the sophistication to be able to understand the inherent value of these stories.

Today’s customer is seemingly split into two distinct groups: firstly, an increasingly wealthy middle class, made up of mainly working professionals with rising disposable incomes and purchasing power, who are willing to save and then spend their month’s salary on the latest It bag, and who form the core of the luxury consumer base. For them, branded goods still retain some semblance of status and prestige, of having ‘made it’ in life. They treat themselves by splurging on these items, celebrating their first pay check; a major promotion; a year-end bonus.

And then there is the elite, affluent upper class, who have come to realise that luxury has become almost affordable for the masses, and who crave the uniqueness and individuality that wealth used to be privy to. When luxury becomes mass, it is no longer luxury; this elite begins to shun luxury brands, except for the most exclusive and expensive products. Luxury, to them, has a new, subtler face these days, as embodied in custom-made products and tailored experiences—things that only the truly rich can afford.