The day David Bowie died, we wept not for one man but for his many iterations: Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke, Major Tom, the Goblin King. Reminiscences poured in extolling his chameleon-like nature, mutability, and constant reinvention. On social media, friends began posting pictures of themselves dressed as Bowie for Halloween. Analeigh, a girl I had studied abroad with, posted a photo of herself dressed as Ziggy Stardust at a party we attended that semester. This had been a last-ditch costume after three failed attempts, but in that picture she embodies precisely Ziggy’s androgyny and verve—never mind that she had scarcely any familiarity with Bowie’s oeuvre. I remember think- ing that this lipstick lightning bolt afterthought was an insult, for surely mimicry should stem from informed idolatry at the very least.

Already decked out as Maude from Harold and Maude, I was jealous all the same. That should have been me. But she was a white girl with sharp cheekbones; I was an apple faced Chinese girl. It didn’t matter which of us was the Bowie superfan. Bowie’s power, pundits wrote, lay in his ability to be anything. But not everyone can be Bowie.

In the politics of embodiment, optics matter, much as we are loathe to admit it. Superficial valence occludes boundless transmutation. Unlike gender, race and ethnicity are never fully performative because it is rarely a mutually traversable state: Rachel Dolezal enacts blackness and Katy Perry dresses as a ‘geisha’, but I bristle at being Bowie. Beyond histories of oppression and colonization, skin color and bone structure blight the confidence of a non-white person to embody the Thin White Duke. I bet Katy Perry didn’t even pause before donning that kimono. I noted in particular the self-policing of my aspiration: even before others might have puzzled over my costume, I had already summarily rejected any chance that I could ever pull off becoming Bowie. I wasn’t lithe enough, my nose wasn’t sharp, my cheeks were too fat. Having escaped girlhood relatively unscathed from incurring body image issues, this Halloween encounter was bringing out all manner of criticisms I had never lobbed at myself before.

Even as someone who has never aspired to look like the thin, blonde models on the cover of magazines, by being unable to imagine myself as Bowie, I realized there were still ways in which I placed limits on how I looked and who I could be. Yet the transposing of Western beauty standards onto that of Asians' is usually more far-reaching and insidious than such a direct comparison.

Think of the seemingly endless whitening products hawked to us—it’s been years since I’ve watched Singaporean television and I’m almost sure I can recite some of those commercials verbatim. Consider the most common cosmetic surgeries elected in Asia: double-eyelid surgery, rhinoplasties, and jaw-line shaping—all modifications to achieve more Caucasian-looking features. Double-eyelid surgery is so common in South Korea that it is nicknamed ‘lunch cosmetic,’ after patrons who nip in and out of the clinic during breaks from work or school. A dimension which subtends this dynamic is that while Asian men are regularly seen by non-Asian women as less attractive mates, as reflected by research collated from dating applications such as OKCupid, Asian women are often fetishized in the Western imagination, and the ones deemed attractive are those who conform most closely to those valorised Western features. Taking it a step further, these features being passed down in Asian populations can also be markers of a history of colonization. Our feedback loop for beauty standards reverberates many times over and echoes in different directions in our globalized world.

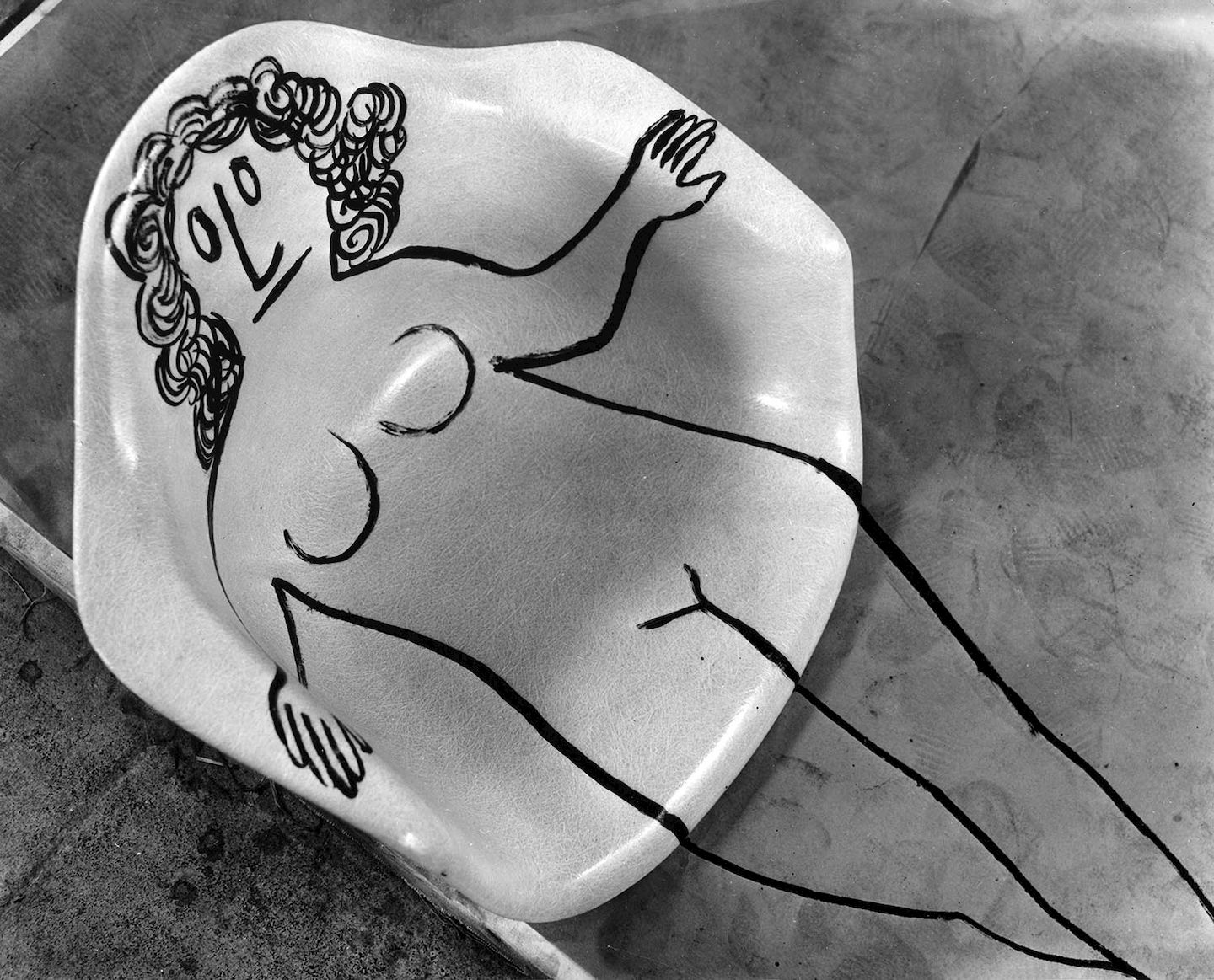

I was recently at a screening of the Chinese artist Wang Xu’s short film, Eve and David. It documents how, commissioned by a commercial mall in China to create a sculpture for their atrium, Wang travelled to the Quyang county where factories produce replicas of Grecian-style statues that are shipped all over the world. Using statues of Eve and David as his raw materials, Wang sculpted them into the likeness of two workers from the factory where they were produced. When he presented his final work to the mall, it was rejected. Though Wang was hesitant to peg his film as a critique on the East’s valorisation of Western beauty when probed, it may certainly be viewed as such. Chinese workers in Quyang spend their days mass-producing statues in the mold of classic Greek gods and goddesses, their hands chiselling deep-set eyes and high cheekbones probably dissimilar to their own visages. Wang has taken the labourers and made them the subjects, he as the sculptor labouring over their image instead. The mall developers’ rejection of Eve and Da- vid, recast as Chinese, as viable public art cements the self-hatred that can pervade Asian culture and how we continually and uncritically turn West-ward for beauty. Had Wang simply submitted the Grecian replicas prior to artistic intervention, might it have gone over better? Here I proffer a last recourse: Eve and David may be salvaged with a little ‘lunchtime cosmetic’ trip.