Worlds within Worlds

by Clifford Loh

Worlds within Worlds

by Clifford Loh

Whilst physical teleportation is still an insurmountable task for most around the world, some amongst us have relied on triggering and enlivening the senses so as to create suitable conditions for the mind to travel. The transportive capabilities of the olfactory is one such instance.

Smell, as Brodsky once wrote, is not just an imbalance in oxygen but also a trigger to some deeper atavistic piety. We enjoy what we smell because someone with these genes, older than ours, did so as well. To the patient observer, the world of scents is a titillating sensorium, capable of activating every inch of our imagination, experience, and memory. It condenses time—past, present, and future—altering our perception of space and surrounds, near and far. With a whiff or a spritz, a corridor takes shape in our minds. Like a portal, it grants us the freedom to be taken anywhere.

These in-between spaces can also come in various physical forms. An elevator, a stairwell, the subway. As interstitial spaces that connect us from one point to another, they require of us the least degree of intent in actually being there. They are least likely to be conscious destinations and therefore possess the greatest potential for serendipitous encounters and revelations. In art, architecture, political theory, and science fiction, interstitial spaces are proposed as sites of poetic resistance, challenging fixed notions, frameworks, and definitions. Offering alternative modes of thought, they stretch our imaginations not of what is there but of the potentialities of what we could be.

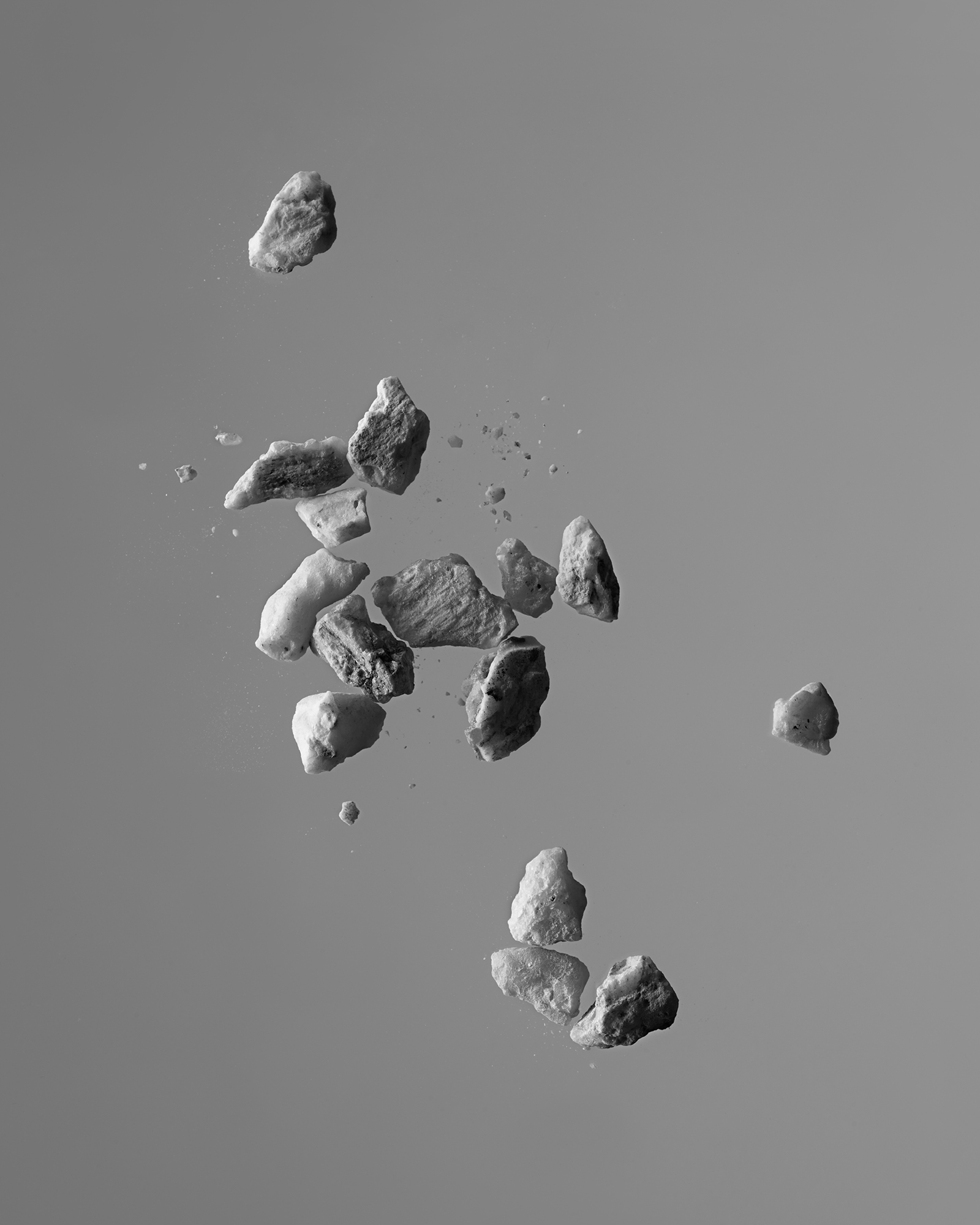

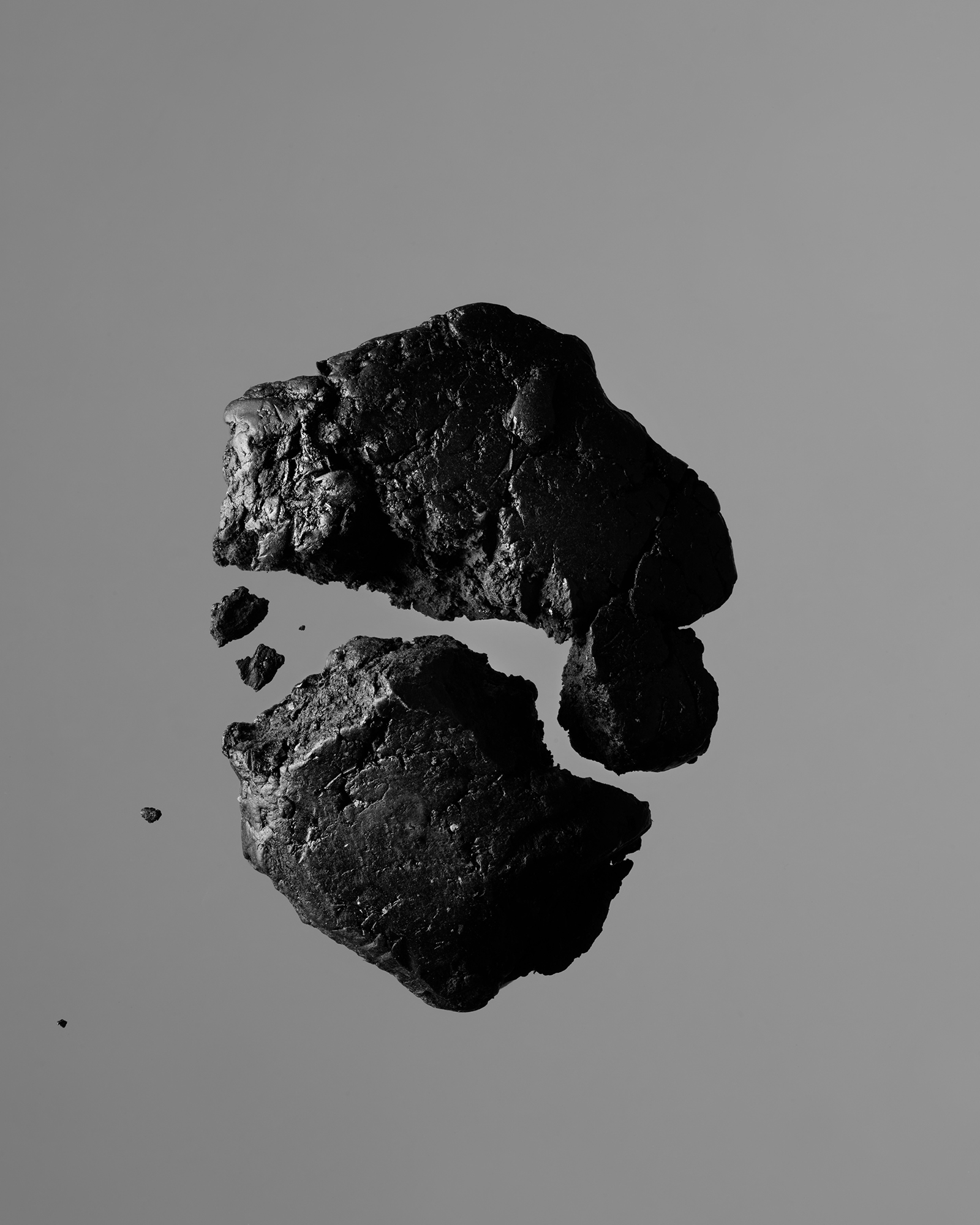

Drawn to the elusive concept of other spaces, long-time collaborator of Aesop, Barnabe Fillion nosed a collection of three new eau de parfums that toys with our perception of the real and imagined. Entitled Othertopias, notes gradually transform with a wearer’s warmth, conjuring an image not of vividly virid foliage or summery spice markets as observed in past iterations like Tacit and Marrakech Intense but of disorienting images of non-existent landscapes between everywhere and nowhere. They brim with quiet revelations and stirring, mysterious imagery: a wasteland of decayed wood, and a boat creeping gently abreast the residual tides of an ocean's waves. There are also cities in the dust. Cities with the rubble of concrete buildings that were once part of a short-lived experiment with urban development, now overgrown with vegetation. Whatever images these words and smells may conjure for you, they are clearly yours to make.

In the following interview, Fillion recalls the unorthodox approach and preeminent thinking that informed his latest contribution to the Australian skincare brand.

Rozū eau de parfum, your last contribution to Aesop debuted in April 2020. How does the latest trio of fragrances fit into Aesop’s repertoire of existing fragrances?

It has been almost eight years since we first collaborated together. The first approach with Marrakech Intense was to simply play and jump into the world of perfume. The concept for Hwyl came from a very dear place of inspiration for me: Yakushima, Japan. We wanted to explore the meaning of a place of shelter, and how we could translate this into an ‘Aesop’ shelter. Rōzu was about extending the palette of ingredients, and the thought of building an aromatic family at Aesop. As we didn’t have a floral perfume, the idea was to go for the rose, especially in connection to the friendship I had with the family of Charlotte Perriand—how we could introduce that rose that was made for her and in homage to life in Japan.

How have these three fragrances complemented or enriched Aesop’s position on perfumery and sensory pleasure?

There is a real desire to create more impact on the level of research that we've been doing with perfumery. It was also actually a collection of six perfumes, and we were wondering how many we will launch at the beginning. Numbers have always been important at Aesop and I think six would have been too much information at once. So three is quite a good number. Spacing it out in this manner allows older ranges of perfume to be solid stand alones with very different profiles. Othertopias (and all Aesop fragrances) sit comfortably within the niche segment of our fragrance world. These aromas are distinctly set apart by their complexity in terms of overarching concept and profile.

How did the concept of Othertopias come about? Can you explain the idea of liminal spaces in relation to these three fragrances?

It started with the conversations that I had while traveling. I was thinking about interstitial spaces that were composed of different chronologies. They are sort of passage places from which you come in and come out. Another starting point of research was Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space—the idea of being connected to abstract, political, and geographical space inspired by those texts by the great figure [through the written word]. And we found it was an interesting way to think about the collection of perfumes. Speaking to Aesop’s founder Dennis Paphitis, it became crucial for us to pick up some of the most important images of space that those different philosophers inspired but also to play with the idea of juxtaposition of those elements in a collection.

Seeing perfumery juxtaposed with literature, geography, and philosophy, we wanted to interrogate what we are doing and thought of that as an invitation for people to wonder about their own relation to interstitial spaces. Each perfume is like a tool to measure these relations. For instance, Erémia is about nature taking over grey concrete cities, and its rhythm and cycles are such that even concrete can’t go against. Miraceti is more like the imminent captain who cannot let go of his furious desires. He knows he is not going to get it but he can’t let go. Karst on the other hand, is a dialogue with nature, it’s about the exchange between inhalation and exhalation but also the small movements triggered by the moon on the sea. This dichotomy is revealing the forces that we never quite imagined were around. It is also an homage to Nietzsche who said that the best perfume is pure air. So it is about the definition of what pure air is and how you make a perfume that smells like air.

"Seeing perfumery juxtaposed with literature, geography, and philosophy, we wanted to interrogate what we are doing and thought of that as an invitation for people to wonder about their own relation to interstitial spaces. Each perfume is like a tool to measure these relations."Barnabe Fillion

It all sounds very cerebral..

We use these concepts from philosophy to start our interrogation but we don’t try to answer. We don’t want to figure it out, we just want to invite people to think about them. You’ll see when you experience them in person, there’s a certain sense of off-ness about it. They are not from one olfactory family. There is always that sort of illusion of a certain space, and then it grows into something else, that's what I played with.

Speaking about “off-ness,” the three key prompts: the boat, the wasteland, and the shore evoke images of desolation or decay for me—whether of salinity, ambivalence, or sense of disorientation. While there are still strong connections to nature, it appears less vegetal and perhaps more elemental (ie. air and water.) The campaign imagery by Davide Quayola also reminded me of synesthesia or a psychedelic trip where the lines between clear forms start to blur and where colours bleed into one another. There is a real tension that upsets the equilibrium between seemingly opposing forces.

That’s an accurate observation which I find very interesting. There is a lot of different layers to this new composition but I suppose the elements are something that inform philosophy and alchemy. With Othertopias, we were trying to offer more meaning by looking at the world as you observed—whether through synesthesia or other phenomena—a little differently. This twisted perception that perhaps last for two seconds allows you to see the world differently.

I often ponder about what “natural” means when encountering Aesop scents. On one hand, a wearer might associate “botanicals” and “plant-based” with the incorporation of essential oils in Aesop products but on the other hand, the intensity levels, treatment, and the combination of disparate ingredients are not natural at all, this composite is on some level artificial. In a way, one might argue that the coexistence between the natural and the synthetic is required for the fragrance to exist. It is not entirely natural even though it might appear to be.

For me, coexistence is a sign of intelligence. Aesop is a brand that has been challenging conventions since the beginning. At the same time, it needs to answer to a certain function. This function comes from nature and serves the science [behind product formulations.] To a certain degree, these are not opposites. In my formulations for instance, I'm using natural oils. So, what you call the “non-natural” is what I call the isolates. They are elements coming from nature and natural ingredients that contain 200 molecules and we only want two of them. In this process of distillation, it is about being precise, and going deeper into a certain subject. While using 100% of the raw material is fantastic, it could also be limiting, in the sense of its affective function.

The brand works with perfume as a function. The scents that are in all of its products are there for its effect on the skin, though, mostly on the hair. And to think of that angle of function always puts me in a certain radicalism and minimalism in the way I work. It shouldn't be decorative even if it's related to aesthetics. It cannot be limited to that because that functional approach is what makes the brand magical and created its signature. I think it comes from coherence, and that's not always the case.

"For me, coexistence is a sign of intelligence. Aesop is a brand that has been challenging conventions since the beginning. At the same time, it needs to answer to a certain function."

There is a tendency for other fragrance houses to price their perfumes uniformly but this is not the case at Aesop. At $265/ 50ml, the Othertopias collection is priced significantly higher than Marrakech Intense at $120 and Rozū at $180. I assume different ingredients and labour all contributed to the big hike in retail pricing?

You’re right, it’s all of that. In Miraceti, I used styrax, labdanum, and elements that are extremely expensive and difficult to use in terms of legislation so we had to figure out the best way to dose them very well. We used ambrette, which is the only vegetal musk note that originates from the hibiscus seed. There is almost no oil in the seed so it smells fantastic in an addictive way. So it’s not only got to do with the fact that they are expensive ingredients, these ingredients are also difficult to use nowadays.

Another interesting aspect that was revealed during research was material history. Grey amber (ambergris) is an animal by-product that we’ve avoided. But then, I went into the inventory and discovered the descriptions of the first people that founded grey amber in the 18th century. It’s incredible to find an exhaustive list of ingredients like tobacco, seaweed, hay, and tea. These ingredients guided me to recreate the note without any animal by-products.

When we last spoke in 2017, you mentioned Hwyl is best worn in colder climates, such as in the winter. Are there particular scents in Othertopias that work better in certain climates than others? What are some unconventional ways you might recommend wearing these perfumes?

The essence of the perfumes cannot be captured based on season, region, or gender. Part of the invitation of this collection is really about appealing to individual interests. The wearer has to imagine that there are no rules. It's just about your reverie and reality, and how you imagine these liminal spaces.