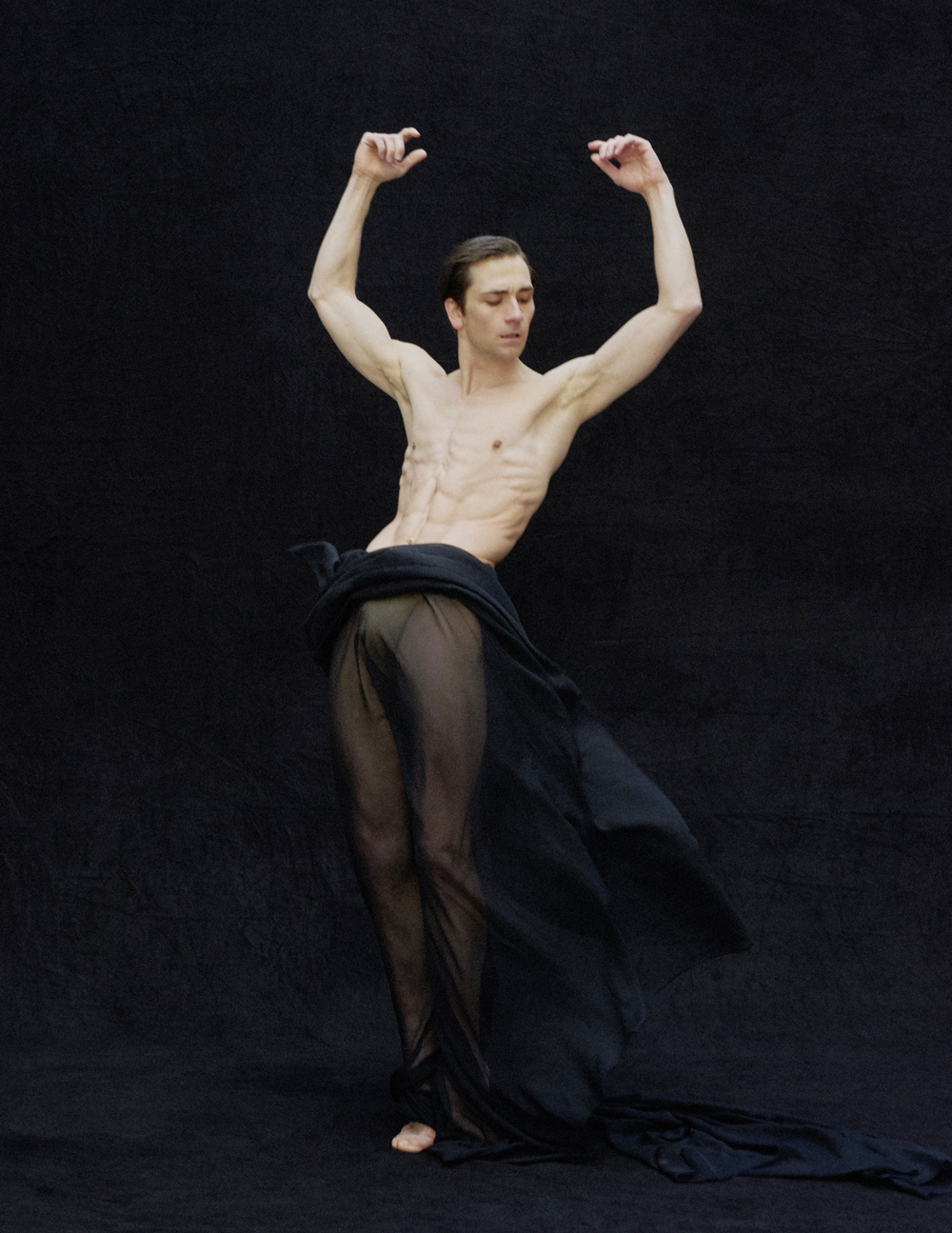

The Man in Tights

photography KOSMAS PAVLOS

text BIANCA HUSODO

grooming MAX ARTEMIS

photo assistant MAXWELL ODERO

top, dresser, trousers CHRISTINA SEEWALD

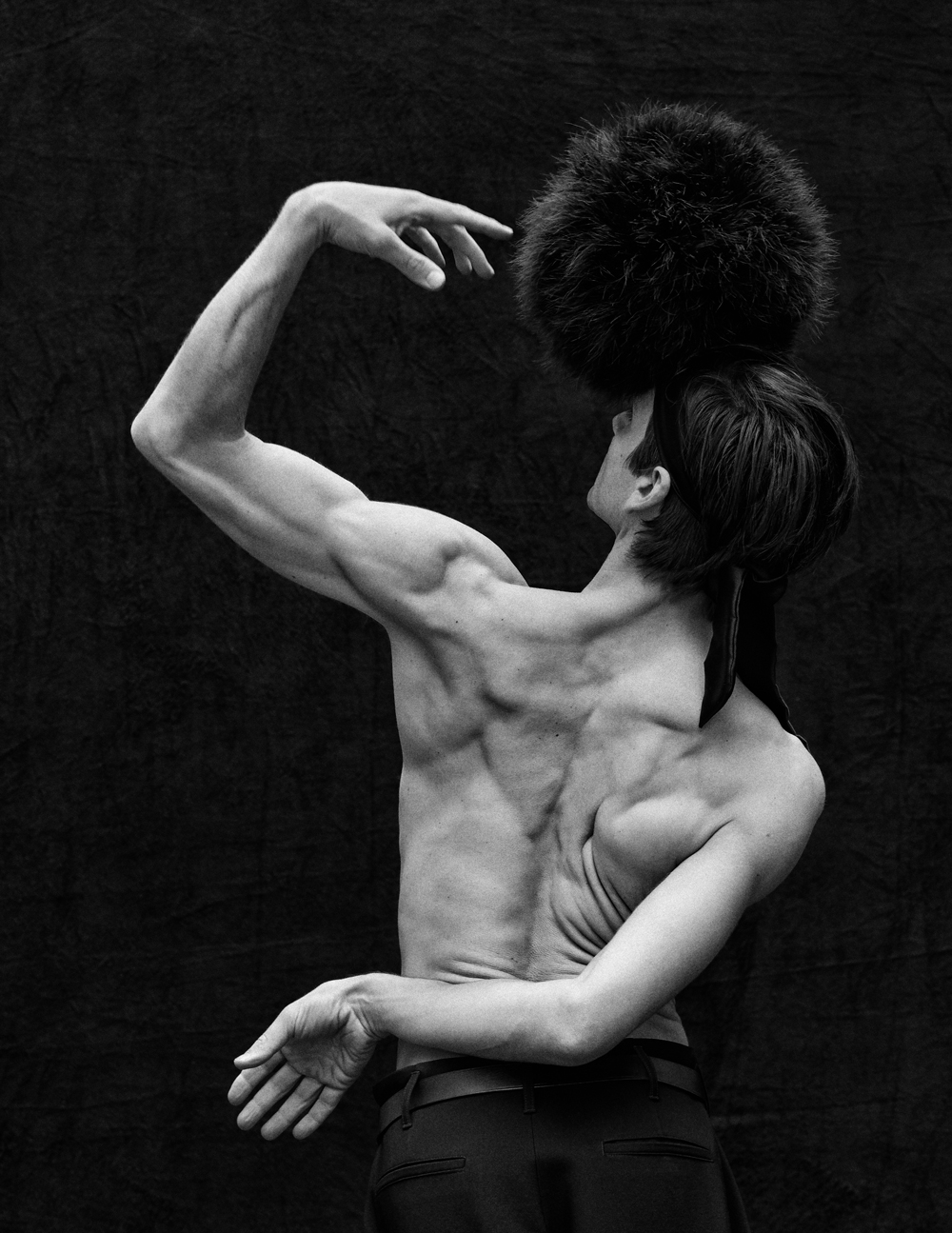

headpieces SASSA ANN VAN WYK

with FRIEDEMANN VOGEL

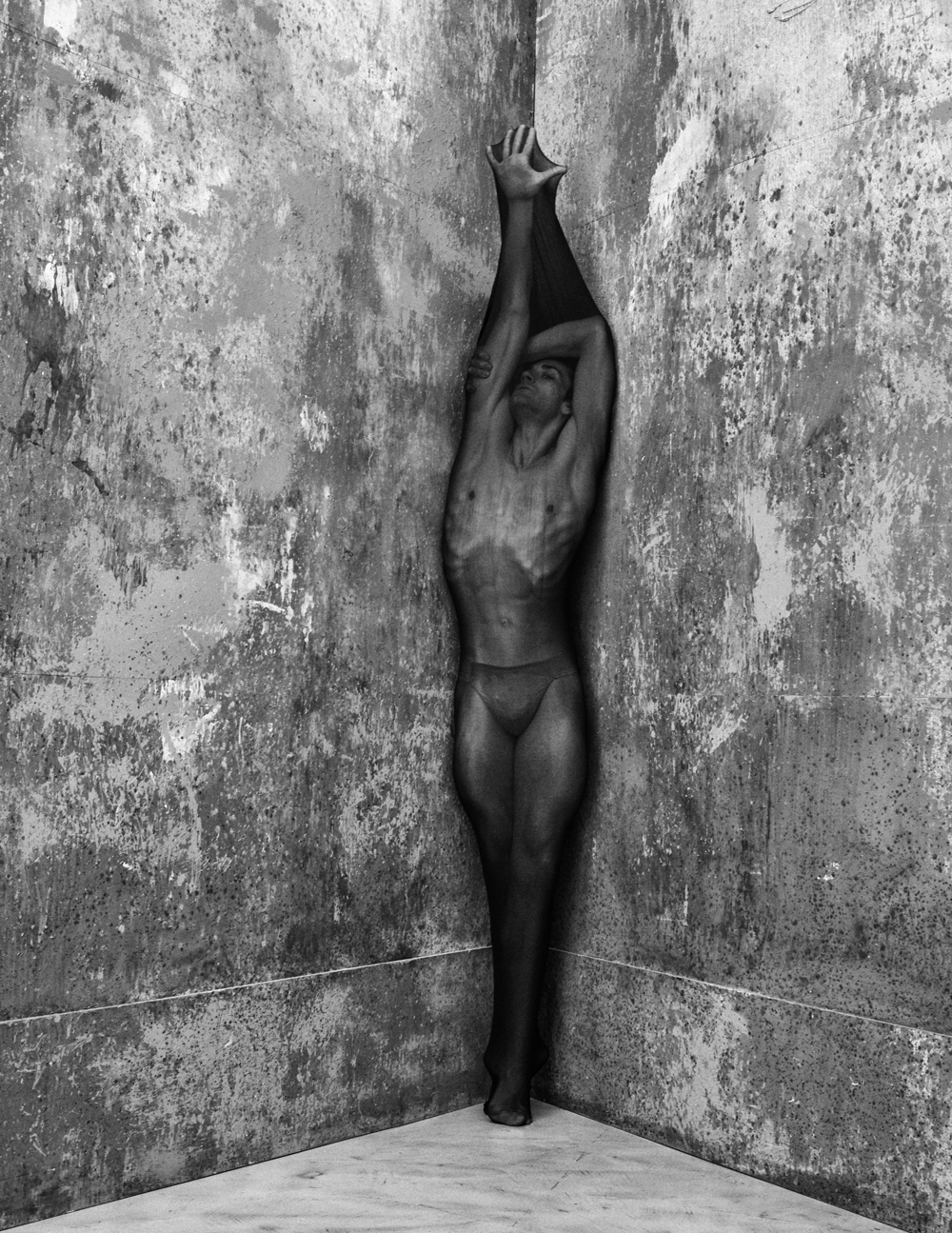

In ballet, the body is paramount. Like their female counterparts, male ballet dancers have increasingly come to be living embodiments of an ideal type of beauty, strength and form.

It is in this aesthetic universe that male ballet dancers like Friedemann Vogel have been striving to fight the stereotypical image of ballet boys in tights confined to the classical domain. To get to where he is now — a Kammertänzer and an étoile at the prestigious Stuttgart Ballet, as well as one of the most critically acclaimed dancers today equally celebrated for his classical and contemporary work — is to continuously defy rigid norms, both in ballet and the real world.

“Boys and men who do ballet must be either exceptionally brave or foolhardy, or both,” writes art historian Jennifer Fisher.

“It’s not very normal in Germany to become a dancer as a boy,” Vogel says, who began his formal training at eight. “But for me, it was the most normal thing.” By 1997, a 17- year-old Vogel won the Prix de Lausanne, a prize awarded to young dancers predicted to be future dance greats. The following year, the Stuttgart Ballet employed him. Within four years, he became its principal dancer, playing leading roles in the most famous ballets from Romeo to The Sleeping Beauty’s aptly named Prince Désiré, to interpreting provocative new creations.

Vogel wears tights, plays princes, and pirouettes, but not just. His body, albeit sculpted to what can be perceived as heteromasculine perfection, continuously blurs normative lines into a realm where the reality of binaries is beside the point. “Is it really that important to separate masculinity and femininity?” asks Vogel. “What matters is authenticity. It's the first lesson I learned: don't be afraid to be unique.”