Globalisation and its impact on local societies can be a source of anxiety among nations and its peoples. For the upcoming Bangkok Art Biennale 2018, Dr. Apinan Poshyananda and his team of curators worked with 75 artists to reflect upon the theme ‘Beyond Bliss’, which addresses the climate of fear and change that underpins global politics, while looking towards possibilities for the future.

The biennale has become one of the preferred models for showcasing contemporary art, and you don’t need to look far to find evidence of the biennale boom. Just within the Asia-Pacific, cities such as Shanghai, Gwangju, and Kochi-Muziris are among the several other locations gearing up to host biennales later this year. In the Southeast Asian region, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and Manila all held biennales late last year and early this year, with Singapore currently preparing for its biennale in 2019. The proliferation of biennales, particularly within this region, demonstrates a concerted effort pushing for communities outside Western frameworks to not just produce contemporary art but present it—and in the process, reposition ‘centres’ of contemporary art. By stretching the potentials of formats of display which are available across different geopolitical settings, curators, scholars, and artists expand perceptions of what art is, who it is for, and how it is to be related to by its audiences. The end-goal might not be to establish new hierarchies for understanding contemporary art in a global context, but to highlight the multiplicity of perspectives that exist in the world; and, if we are able, to find value and joy in negotiating in that diversity, rather than being stymied by the unknown.

The upcoming inaugural Bangkok Art Biennale finds itself amidst the buzz of biennale season. From 19 October 2018–3 February 2019, Bangkok Art Biennale 2018 will situate international contemporary art within the rich cultural landscape of Bangkok. Artworks will be housed in some of Bangkok’s most famous heritage sites, such as the ancient temples Wat Pho (Temple of Reclining Buddha) and Wat Prayoon (Temple of Iron Fence). The theme, Beyond Bliss, threads across the broad scope of artists and exhibition sites. One can expect Bangkok Art Biennale 2018 to be as much about the art as the architectural and urban history of Bangkok, as well as Thai hospitality. Adding to the spectacular extravaganza are showings by world- renowned figures in the arts, namely Yayoi Kusama and Jean Michel Basquiat, both of whom are slated to be featured in the line-up of 75 participating artists alongside emerging artists, such as Kray Chen from Singapore. One notable programme developed for the Bangkok Art Biennale is the collaboration with the Marina Abramovìc Institute. It invites performance artists in Asia to work alongside the artist and her team for an exhibition lasting three weeks. The Bangkok Art Biennale is brimming with promise, and the association of Bangkok with Venice in advertising campaigns (‘Venice of the East’) sets a high bar for the inaugural show.

"There is this political imagination of ASEAN as a dream community—ten countries discussing ideologically together, but life is not as ideal as politicians want it to be."Apinan Poshyananda

But Bangkok isn’t Venice, and it’s important that the Bangkok Art Biennale also sets itself apart from the Venice Biennale—an established exhibition model which has been criticised for becoming increasingly commercial over the years. It will be exciting to see how the Bangkok Art Biennale 2018 is presented, for the first time, in a world whose ‘blissfulness’ is certainly debatable. The theme of the inaugural biennale provokes going beyond a perfect state of happiness, and viewers can look forward to discovering what that entails through works of art that respond to and energise the urban spaces of Thailand’s capital city.

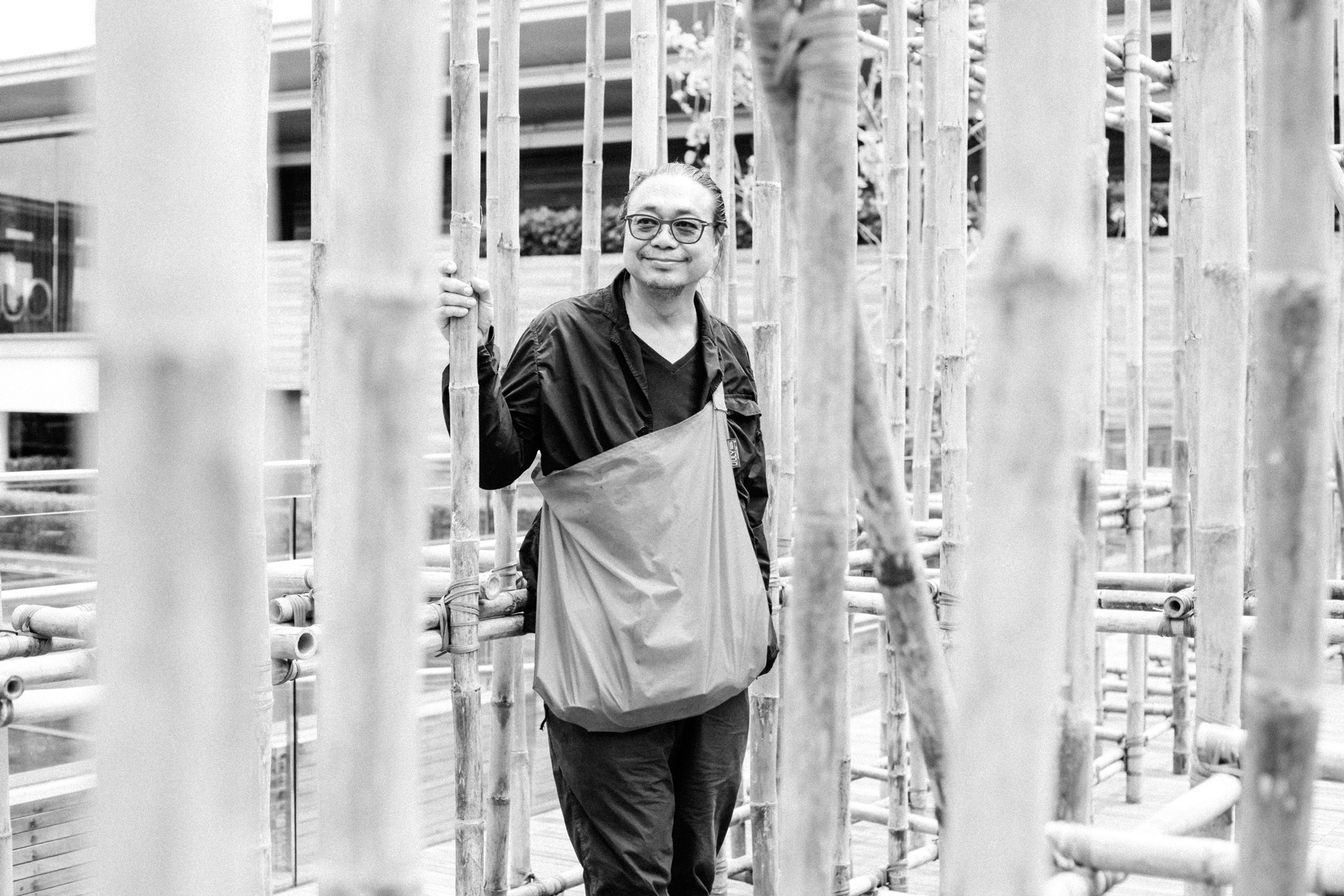

For Bangkok, this inaugural biennale ushers in growth and change. "The idea [for a biennale] has been brewing for many years, but Bangkok hasn’t been ready to have such an international platform because of the political, social or economic situation,” explained Dr. Apinan Poshyananda, Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the Bangkok Art Biennale 2018, “but this is the time.” Bangkok is now ready. For Dr. Apinan Poshyananda, championing Thailand’s creative culture has been a prolonged endeavour. Trained as an artist and a scholar, he has served as Director-General for the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture, as well as Permanent Secretary and Acting Minister for the Ministry of Culture, Thailand. Vulture sat down with Dr. Apinan Poshyananda to discuss his vision for the Bangkok Art Biennale, its importance to the discourse on contemporary art in Southeast Asia, as well as its impact on the urban reimagination of Bangkok.

Apart from enlisting key figures in the Thai art scene, such as Luckana Kunavichayanont and Sansern Milindasuta, the curatorial team also includes prominent Southeast Asian scholar-curators, Patrick D. Flores and Adele Tan from National Gallery Singapore. How does the curatorial direction of Bangkok Art Biennale add to the academic discourses you mentioned above?

Southeast Asia has scholars who can be curators and scholars, and that’s what we really need. People are challenging the role of the curator—it is now [a title] too widely used—so it’s a good time to think about the positioning of curators. We need to have curators in biennales and we need to have artists in biennales. We can discuss and debate and find alternatives. There is no right or wrong; it is an evolving context. [With regard to] issues within Southeast Asia, there is this political imagination of ASEAN as a dream community—ten countries discussing ideologically together, but life is not as ideal as politicians want it to be. In this way, we want representatives from Southeast Asia to reflect on issues that are often overlooked, such as inequality and gender, and other ongoing problems that are hard to discuss in a meeting about economics or finance. For the next Bangkok Art Biennale, we hope to invite curators from other regions as well.

When you were Director-General at the Department of Cultural Promotion, you said that “bridging heritage and contemporary art [was] the main mission”. Do you think this aim carries forward into the Bangkok Art Biennale 2018?

I was Director-General of that department a while ago, after which I became Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Culture. I continued to pursue the idea that contemporary art and heritage go hand in hand. A lot of people feel that there are marked boundaries—[that] contemporary art cannot enter places of worship or heritage. However, artists have been looking at artefacts for hundreds of years in Thailand. It is a dialogue between the past and the present, this fusion of creativity. Instead of parachuting the artists in—where they don’t know where their art will be—we asked artists to do site visits so that it’s part of the research. Some of them had a chance to look around and the rapport has been great.

What do you anticipate the public reception of this fusion of contemporary art and heritage will be like?

The Thai audience have their preconceptions about what temples should be. However, in the 19th century, for example, there were a lot of exchanges, not just of faith and religion, but also of knowledge in the Temple of Wat Pho (Temple of Reclining Buddha). We want to show that these are places where knowledge is accumulated. A lot of people have this idea that if you put contemporary art in heritage sites or temples, artists will make controversial works. This is a grand misconception. The artists have studied the sites and they feel this connection. We want to ask the Thai audience to learn with us, to go along with the artists’ interpretations. We want people to spend time in the local context and really experience their journeys. Part of Beyond Bliss is taking things slower. It’s not just like, “oh, we are done with Bangkok, so we are moving on to Shanghai”. People might complain that there are too many venues, but it’s not a problem. They can complain—we live in a culture of complaining anyway. There are many ways to have a biennale. We want to have slower movement, by boat, by experiencing communities. I think [it is an opportunity] for people to really contemplate. You never know, [visitors] might just find their own bliss walking along the streets of Bangkok.