Someone with wings, horns, tails, fins, claws, reversed feet, head, hands. Anyone with additional arms, legs, eyes, breasts, genitals, ears, nose, lips, head. Anyone without a face. Pinheads, dwarfs, giants, Satyrs...

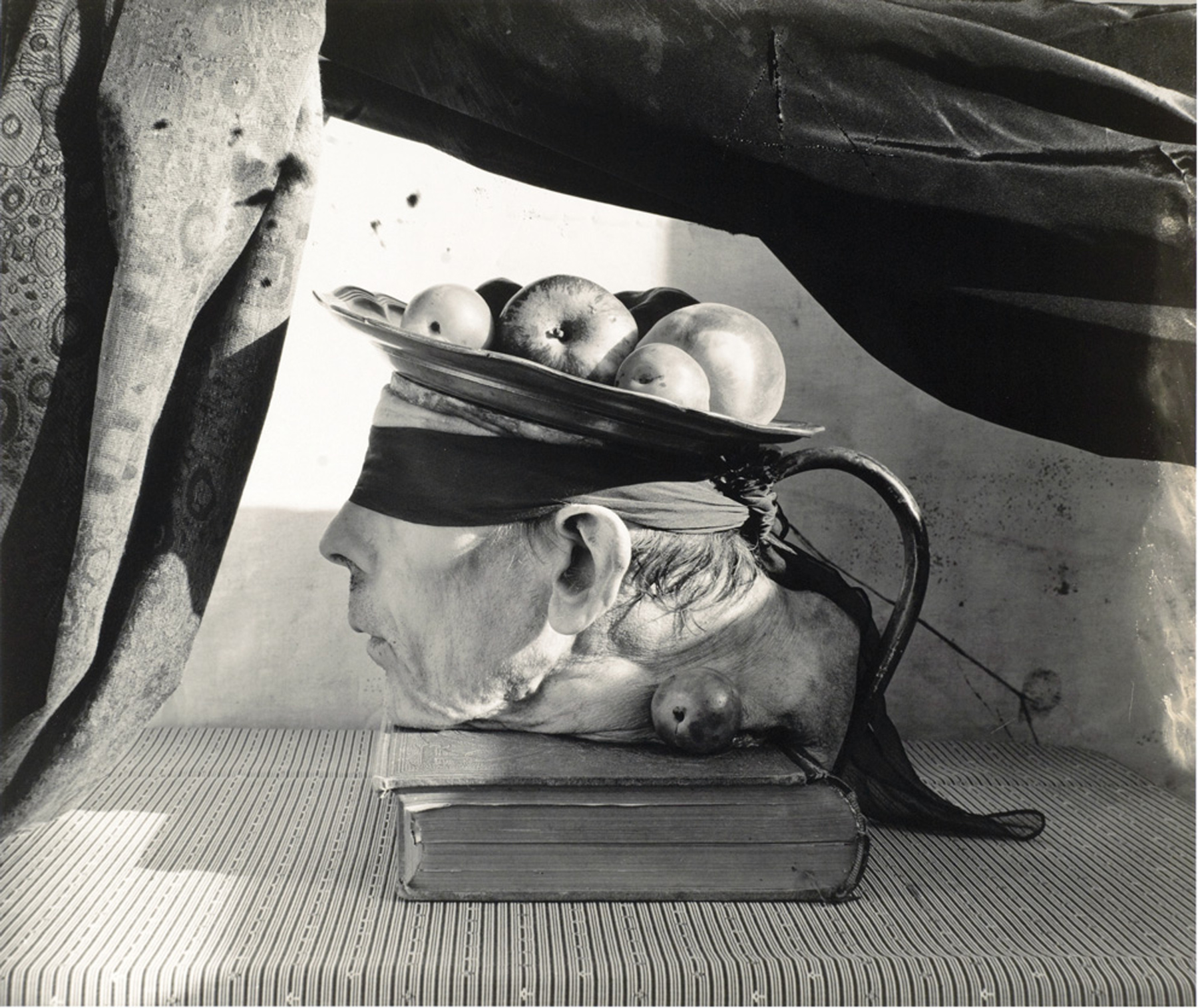

Awesome and terrible, erotic and grotesque, romantic and criminally insane—these are the paradoxes that have come to characterize the works of photographers Joel-Peter Witkin and Nobuyoshi Araki. These are works that draw us into the irreconcilable gulf between contradictory emotions. They induce in us a hypnotic vertigo that disorients our aesthetic bearings even as it keeps us transfixed. Whether because of physiological reflexes or out of moral propriety, our instinct is to look away. Yet this repulsion is matched with an attraction that challenges us to stay with the work. The images—of severed heads, and of exposed genitals—bring us to the thresholds of our conventional notions of beauty, transgressing taboos and transfiguring death. They are monstrous in their radical otherness and they override our sensibilities of the normal.

In an open casting call, Joel-Peter Witkin declares he needs as models “physical marvels” that are so extraordinary as to inspire wonder. He then provided the most abominable and fantastical litany of abjection, from Satyrs to bondage fetishists to the severed heads of corpses. Witkin assiduously searches for his subjects while riding the New York subways, working as a headwaiter in an Albuquerque restaurant, attending the conventions of tattoo artists, always alert to potential collaborators. His aspirations are nothing short of the monstrously sublime. “To me extreme things are like miracles. There is nothing as boring as a person who is just okay.” Detractors accuse Witkin of exploiting his subjects for their shock factor: their perverse depictions resemble little more than a Victorian freak show. However, Witkin's engagement with these physical marvels are neither fetishistic or superficial. It is religiously humane. He explains that through his meticulously arranged photographic tableaux, he intends to lift them beyond their decrepitude, transcending subject matter, and entering what he calls a world of love and redemption: “The figures were always isolated because the Sacred is always beyond nature, beyond existence.”

In Un Santo Oscuro, Witkin presents a figure that is truly “beyond existence.” What first appears to be a broken mannequin is in fact a living person whose mother took the drug thalidomide to combat morning sickness during pregnancy, unaware of its side-effects. He was born armless, legless, without eyelids, with half-formed skin and lived in bandages enduring constant pain. When signing his model release, the man requested: “Whatever you do, Joel, make me look like a real human being.” Familiar with Spanish paintings of clerics depicted as martyrs, Witkin posed his model with his wife's cleaver and a chain-mail collar. Arrows and knives pierce him like a modern Saint Sebastian. The man longed to be redeemed as human and Witkin transformed him into a martyr bearing the stigmata of modern suffering, a saint atoning for the sins of humanity.

But if Witkin searches for physical marvels, Araki explores the marvels in the physically banal. Nobuyoshi Araki claims he does not pursue any special subjects, because the world is already so magnificently rich with beauty that he cannot resist shooting everything around him. For Araki, photography is not about artistic expression because he believes that the people truly expressing them are the subjects. Witkin would bring his models back to his studio where he would carefully pose them on his elaborately designed set, suffusing the image with religious iconography and creating a visual allegory. They are sociopolitical critiques and psycho-sexual commentaries about the human condition. Araki, on the other hand, withholds such interventions and maintains: “I have nothing to say. There's no particular message in my photos. The messages come from my subjects, men or women. The subjects will convey what there is to say. I have things to photograph, so I've nothing to express.” Instead of the gravitas that Witkin wields, Araki shoots with the irreverence of “a mischievous boy doing naughty things.”

Araki infamously described the camera as a penis, but he concedes that it is also a vagina, accepting and embracing its subjects. They all have their own charms, even if they aren't aware of it, so it becomes the task of the photographer to discover that “extra-special unique something” in them and present it to them. This approach means that his own preferences are usually submerged to lend primacy to his encounter with the subjects. “Anything and anybody who I have the privilege of encountering is significant in themselves. Some people may seem like assholes, but you have to be accepting enough to think that maybe you're projecting a preconceived idea onto them, and they're not really assholes. That way, you might be able to discover something nice about them.” In this approach, he is not unlike Witkin who, in his own words, seeks the “wonder and beauty in people who are considered by society to be damaged, unclean, dysfunctional, or wretched.”

"... A woman with one breast (center); a woman with breast so large as to require Daliesque supports; women whose faces are covered with hair or large skin lesions and willing to pose in evening gowns..."

Through Araki's prolific portfolio of coital flowers, placid skies and covers for pornographic magazines, women hold him in their thrall: “Women make me live. I will continue photographing them. If one day women disappear from the planet, I would hope to die well before it happened.” In the moving series Sentimental Journey, Araki reveals how his wife, Yoko, made an indelible impression on his photography. He confesses that before Yoko, he took photographs of women as objects, through their genitals, but when he photographed Yoko, he began to capture the intimacy of the relationship between himself and the woman before him. “It was the first time I was taking a woman instead of an object.”

Even in his notorious (bondage) series, Araki is careful to note that it as a gesture of tender embrace instead of pornographic objectification: “I only tie up a woman's body because I know I cannot tie up her heart.” What draws Araki is not the intricacy of the knots, but the involuntary and ephemeral expressions of the women, unfettered by rope. He acknowledges his debt to Japanese Shunga prints, where the genitals are visible, but the rest is hidden by the kimono. Shunga for Araki is not just about the revealing depiction of sex; it is a loving secret between two people, elusive to the grasp of ropes, cameras, and eyes.

A young lady in the traditional garb of a geisha is suspended by ropes, with her legs sprawled open to reveal a carefully positioned flower at the end of a trail of pubic hair. Her kimono is draped along her waist and falls towards the tatami floor. A miniature figure of a Triceratops with its phallic horns wait expectedly below the woman. The model is looking at us, but she also seems to be looking inward: a subtle and enigmatic expression. In the intricate bondage and interventions with the flower and the dinosaur, Araki seems to emulate Witkin's careful design and narration, but both are ultimately gesturing to something that moves us beyond the thing itself, beyond what we see.

"... Boot, corset, and bondage fetishists, a beautiful woman with functional appendages in place of arms, anorexics (preferably bald), the romantic and criminally insane (nude only). All manner of visual perversions..."

Two works come to mind. The Rebirth of Joan Miro in Paris (1981) by Witkin and an untitled photo by Araki in his Tokyo lucky Hole series. Witkin's piece features a denizen of New York's infamous Hellfire Club, a now defunct BDSM nightclub. The model is nude, except for a black hooded mask and the high-heeled boots of a dominatrix. She stands with one leg perched on a stool where a foetus lies prostrate. It is Joan Miro. The picture shifts into a surreal register with cryptic symbols that conflate the paraphernalia of sexual fetishes with the iconography of art history. Araki, on the other hand, is documenting a scene in the notorious red-light district of Kabuki-cho in the Shinjuku area of Tokyo. Three voluptuous women who seem like house-wives in an earlier photograph are now posing in a suite of a “love hotel.” They are in lace stockings and sexy lingerie, brandishing a whip, a handcuff, and a candle. The masks they wear are reminiscent of those prominently featured in Witkin's oeuvre. The women seem to be posing casually, but when considered alongside Witkin's work, they acquire a mythological aura. Perhaps they are the urban Fates of a deviant pantheon.

"... Beings from other planets. Anyone bearing the wounds of Christ. Anyone claiming to be God. God."

The photographer and curator Van Deren Coke asks if Witkin is “a wild wicked man, surveying the world for subjects to shock us, or is he a dreamer searching the darkness for revelations of man’s true nature?” A similar quandary is posed about Araki's work as pornography and as art. Is there a sincerity in these perversions that move beyond the exploitative? Are they romantic or criminally insane? Perhaps they are both, but it does not really matter. This deeply disquieting ambivalence is what moves these photographs beyond the shock of the freak show, beyond the campiness of pornography.

Witkin and Araki are both committed to the belief that there is a form of beauty in everything, even in the banal and in the deformed. While this is already an inherent truth for Araki, it is a quest for Witkin to become a more loving and unselfish person: “I've been thinking about St. Francis, who had this terrible fear of lepers. One morning he was walking down the road and saw the most grotesque leper and he knew that to get beyond the demise of his own flesh, he had to kiss the leper. And at the instant St. Francis kissed him, the leper turned into Christ.” The transcendental and the divine certainly persists in Witkin's works but I do not think he is looking for God. What we really glean in the works of these two photographers is a search for what it means to be humanly alive.

“And my expression?”

“Imagine you're a god who wants to look human.”