The Invisible Whole of Zentai

by Shawn Chua

by Shawn Chua

“I think zentai can remind us that it is good to be ourselves, the self that exists beyond identities. A group of zentai people look like they are merging into one another, as if they are one whole energy. Zentai takes away not only the identity but also the individuality. It is no longer twenty people standing together but one big energy standing.”

—Yuzuru Maeda

The invisible whole—such is the conceptual body that stretches beyond the corporeal fabric of zentai, traversing across the many folds of identities to gesture towards a wholeness that wears us all. Zentai is the Japanese portmanteau of zenshin taitsu, literally ‘full-body tights’, and it refers to the skin-tight attire that covers the entire body. Truncated as ‘zentai’, it becomes a term which means ‘entirety’ or ‘wholeness’ and connotes a more abstract totality that is not delimited by the boundaries of the individuated body. It is these two layers of meaning that are interwoven in the delicate paradox sheathing zentai, a form that becomes conspicuous as one disappears, where the contours of one’s body become nakedly exposed while being fully covered, and in which the tightly bounded self is stretched towards the community of an invisible whole.

My first contact with zentai occurred in April earlier this year when I chanced upon an open call for ‘Zentai Town.’ This event was part of a larger Zentai Art Festival organized by Yuzuru Maeda, a sprightly artist who was as vibrant as the pink zentai she was wearing. Upon arrival at the meeting point at Lasalle College of the Arts, I wandered about tentatively before I approached a rather conspicuous group of people, some of whom were already in their zentai. Yuzuru warmly greeted me as she sized me up and confirmed the preferred colour, (I indicated black,) and then I was off in a tight toilet cubicle struggling to get into my very first zentai. After a few attempts, tearing a small hole and wearing the suit front-to-back in the process, I walked out in zentai to join the group like a young neophyte who has successfully completed his initiation ritual.

The Zentai Art Project is Yuzuru’s brain-child. Currently based in Singapore, Yuzuru is expanding her musical practice to explore the medium of zentai, creating video- based works, performance installations and curating festivals that incorporate zentai. She invests a deep spirituality in her art, and uses zentai as a means to investigate notions of ‘identity’ and how we come to terms with our living environment. “Invisible Whole” is the title of a series of art exhibitions curated by Yuzuru, and the first iteration took place in November last year at The Substation Gallery, where she invited artists in the region to explore zentai art through photography, performance, moving images and installation.

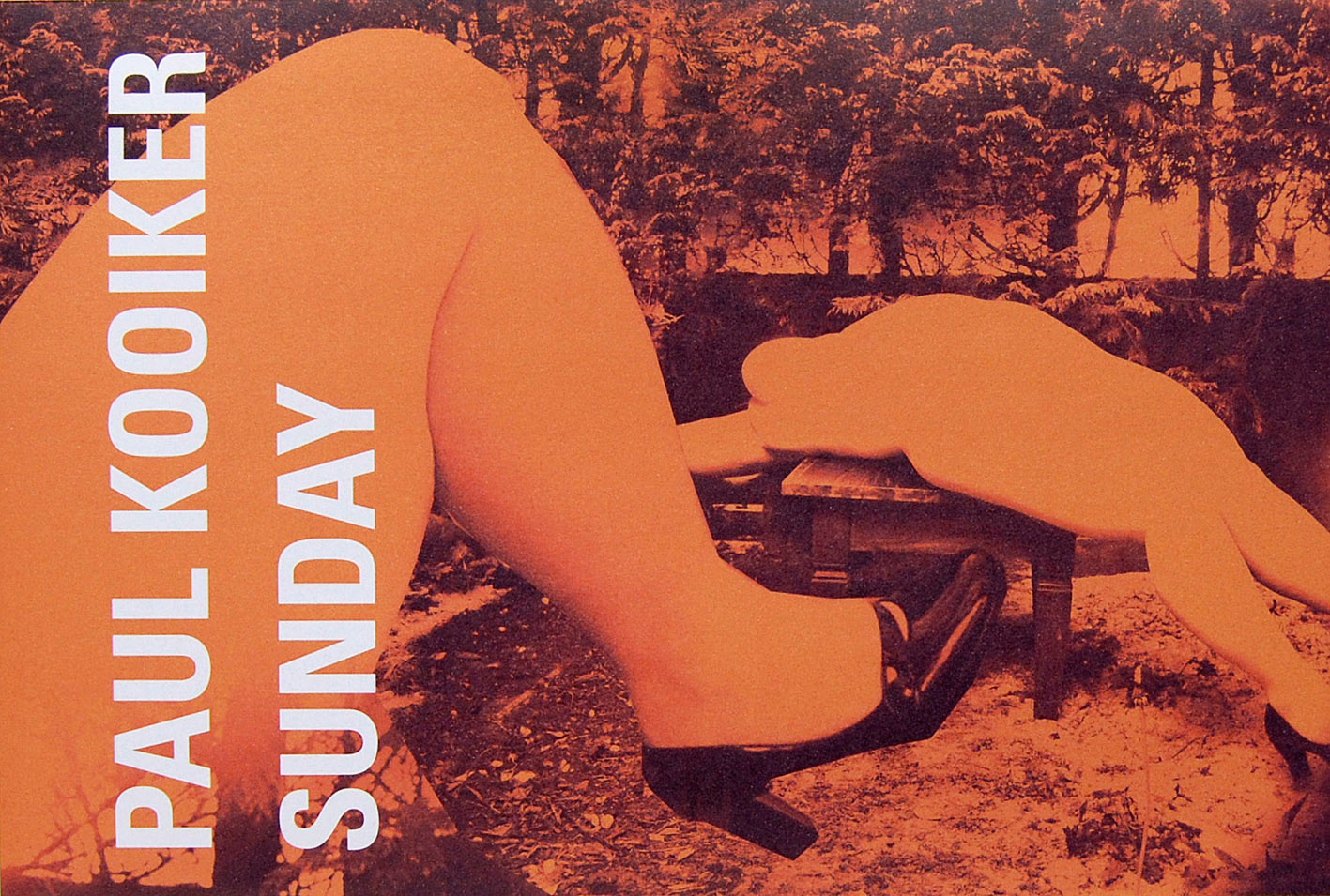

The momentum of zentai art has been developing steadily since then, with the third installment of “Invisible Whole” at the Japan Creative Centre in June this year and a series of other zentai engagements as part of other art events and festivals. Recently, zentai art has also spread to Vietnam and Myanmar, and there are reports of projects being developed in Israel and Switzerland, inspired by the Zentai Art Festival held in Singapore. Yuzuru effaces her own role in this movement, noting that zentai has been around for decades. This is true—the popularization of zentai is commonly attributed to Marcy Anarchy’s experimentation with full body suits in the '80s. However, zentai has mainly circulated within fetish subcultures and it was Yuzuru who brought it into the public eye and began cultivating a burgeoning interest in the artistic and communal potential of zentai. With events like ‘Zentai Walk’ and ‘Zentai Town’, there is no intimidating expectation to ‘perform’. People from all walks of life are invited to roam the streets, or have a picnic, or simply ‘be’ in zentai.

‘Zentai Town’ was a public intervention that engaged with the sensuous urban skin of the city and permeated the pores of the human environment. It was an afternoon that witnessed approximately 30 people in zentai milling about the shops, disappearing into lamp posts and playing with curious passersby along Waterloo street and Bencoolen street. The denizens of the area were a richly heterogenous crowd that comprised of savvy shoppers spilling from the malls at Bugis, devout worshippers on their way to Kwan Im Temple or the adjacent Sri Krishna Temple, art students from neighbouring campuses, street vendors peddling an eclectic variety of wares, volunteers seeking donations and flaneurs of every form. Within the second skin of zentai, the gestures of everyday life were spectacularly transfigured into performance, and in the encounters with our largely unsuspecting audience, I felt the different rhythms and sensibilities that populated the place.

As zentai privileges anonymity or at least the subversion of identity, I have chosen not to reveal the names of the zentai users, and will refer to them instead by the colour of their zentai. In my conversation with Red, he remarked that one of the first things he notices is how your vision is impaired and altered. The different colored zentai suits are like gauzy lenses that refract your vision of the external world, but they also insulate you from the vision of others. In a curious inversion, it is actually the lighter colours like white and yellow which are the most opaque while the darker colours like black and blue are more translucent. This experience is initially disorienting, but it is precisely this vertigo induced by the altered state that psychologically liberates the zentai wearer from the trappings of everyday life. Several zentai users have commented that this impairment of vision intensifies the introspective experience of zentai. They become more meditative and gain a heightened awareness of themselves and the sensual experience of movement.

Yuzuru recounted how a performance artist, Indigo, who was often characterized as being flamboyant and vehement, revealed a gentler and almost maternal side in zentai. Another zentai artist Green countered, that this may have more to do with one’s personality and circumstances than the suit itself, as one can equally likely become gregarious and flamboyant when they are no longer inhibited by the social mores ordinarily expected of them. We tend to privilege nakedness as a site of authenticity, where the performative selves are stripped away to reveal a genuine ‘self’. However, we often fail to acknowledge that the body, our embodied identities, are perhaps the thickest and most stubborn of clothes that we don. For some people, it is the zentai suit that allows them to expose their naked self when the surface identity of their body is obscured. This follows the phenomenological inquiry of Merleau-Ponty who asked how is it that in veiling by our senses, one unveils or perhaps reveals the object. The opposite of the naked skin of authenticity is not clothes, or even zentai, but the avatars of identity that dress us.

Whether one becomes more internal or external, the zentai artists agree that the

partial obscuring of vision leads to a primacy of touch, and emphasizes a certain

tactility of vision. The philosopher and cultural theorist Peter Sloterdijk writes about

the primacy of the face and the intersubjective space between faces, the inter-face of

communication. In tracing the early history of human faciality, he notes that the

Greek etymology of the word for the human face is prosopon, which also refers to a

mask, and it suggests how “humans have faces not for themselves but for others.”

But what happens when one is de-faced by the zentai? The face becomes decentralized from the eyes and the mouth and dispersed into the entirety of the suit, endowing all surface with the expressivity of the face. How we perceive ourselves is in some ways reflected in the faces of others. Zentai, like skin itself, is not merely prophylactic armor that guards the sovereign self from the external world; it also exposes us to face the world. While in zentai, the people I encountered would usually regard me with curiosity, opening themselves to engaging with me, which in turn encouraged me to approach them. Surprisingly playful and even tender moments emerged with people that would have usually disappeared into anonymity of the crowd. I found myself wondering about the prospects of the same encounter happening if I had not been in zentai, would I still be able to tease that child, mimic that lady, or lay my head against that man?

For Yuzuru, zentai opens up an interstitial space between language and identity, beyond the cognitive desire to organize our relations and our selves:

“The mind wants to label, categorize and analyze whatever it experiences. But that is far away from experience itself. The mind translates the experiences through the senses, and emotion into language. But how much can 5 vowels express reality? It limits experiencing the full scale of the world if one perceives the world through languages.”

Zentai sutures the wounds cleaved by the prejudices of ‘identity’ into a seamless whole—a whole with folds, creases and wrinkles but an integrated whole nonetheless. The community of zentai does not lie bounded within those who wear zentai but also with those they encounter. What at first appears to be the boundary of skin, turns out to be the dense skein of intersubjectivity in which we are intricately entangled. When we regard the invisible whole of zentai, we may come to grasp in its sensuous materiality the open mesh of possibilities of who else, and how else, we may be.

“So how do we know who we are? It lies in the silence between words, where things are unconditional.”