In its relatively short history, the Singapore Biennale has witnessed its fair share of contingencies. The Biennale has changed hands since its first iteration in 2006; initially organized by the National Arts Council, it is most recently under the care of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM). The Biennale’s curatorial modus operandi has shapeshifted accordingly, having been helmed by cultural practitioners of different professions and backgrounds, from institutional curators to independent artists and researchers. Lean curatorial teams of three or four in its nascent years have ballooned to a whopping twenty-seven in 2013. Reflected in the choice of artists and thematic concerns, the Biennale’s geopolitical focus has also vacillated between the international and the regional. As a cultural event, the Singapore Biennale has and can therefore be interpreted within various frameworks: as an ennobling backdrop for international trade and global politics, an experimental public playground, and a large-scale museum exhibition of Southeast Asian art.

The sixth edition of the Singapore Biennale will be curated by Patrick Flores, curator and art historian from the Philippines. Through open-ended inquiry, we discuss with Flores the implications, relevance, and urgency of the Singapore Biennale in the midst of its cultural and socio-political fluctuations. How might the local, regional, and international be negotiated, if at all, within its parameters as well as the broader histories of global biennales? Are these categories productive or stultifying? Can various publics work with and shape a biennale’s seemingly gargantuan contours? As Flores writes in his book Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia, “the term ‘curator’ and the act of ‘curation’ [in the region] remain restive signals and refuse to settle into a rigid system of roles and codes.” Likewise, as this short interview will perhaps elucidate, equivocations between stability and instability, knowledge and uncertainty, do not necessarily need to be frowned upon.

In your statement for Singapore Biennale (SB) 2019, you gesture toward the potential of art to effect change in our present 'troubled' times. Your proposition, however, also values failure as 'a step in the right direction.' Could you speak more about your reasons for considering failure as a curatorial method?

In these times of exceptional trouble, I feel that we need to be very patient about process, and in the same breath be urgent about our commitment to step into the fray and make a difference. This relationship between being patient and being urgent should lead us to reconsider the false choice between success and failure. It should prompt us to rethink what it means to fail and what it means to succeed, and to reframe them not so much as endgames but as relays, circulations, series of efforts, attempts. In the French language, to experience is to experiment. And this is exactly what I want to play out in the making and sensing of art in a biennale: a living, persevering labor, and the joy, in trying to make things happen in a seminar-festival sensorium.

I would like to pick up on the contingency that compels your curatorial gesture. Previous editions of the Singapore Biennale have taken place in unique or 'unconventional' spaces, for instance, outside the walls of the art museum/space, in provisional situations that more directly address and engage with publics and their socio-cultural particularities. For example, in the Old Kallang Airport (2011) and various places of worship (2006). What is the importance of these spaces as curatorial venues, and how have you considered them in your artistic direction?

The SAM spaces are being renovated; we won’t be using them for the Biennale, except for the hoardings. This gives SB 2019 the chance to disperse into different islands of spaces across and around the city-state of Singapore. I like this dissipation of the museum monolith in the time of [Singapore’s] colonial bicentennial. As viewers look for and find the Biennale, they get to know or rediscover the city. All exhibitions respond to their site, and so spaces are in themselves agents, or ways of making, knowing, interacting with the other agents in the field. They are not passive, inert receptacles, conveniently regarded as venues. Spaces are central to the life of the Biennale in this respect. And because spaces mean at once embeddedness (strata of prior history, emotional investments of those who inhabit them) and activation (performance, gathering). The role of space deepens in my artistic direction, because it speaks quite cogently to the title, which is Every Step in the Right Direction. This act of deciding to make a step, to take it, and to think through a right direction is an ethical act as well as an aesthetic one, because it anticipates an encounter with art and a possible future.

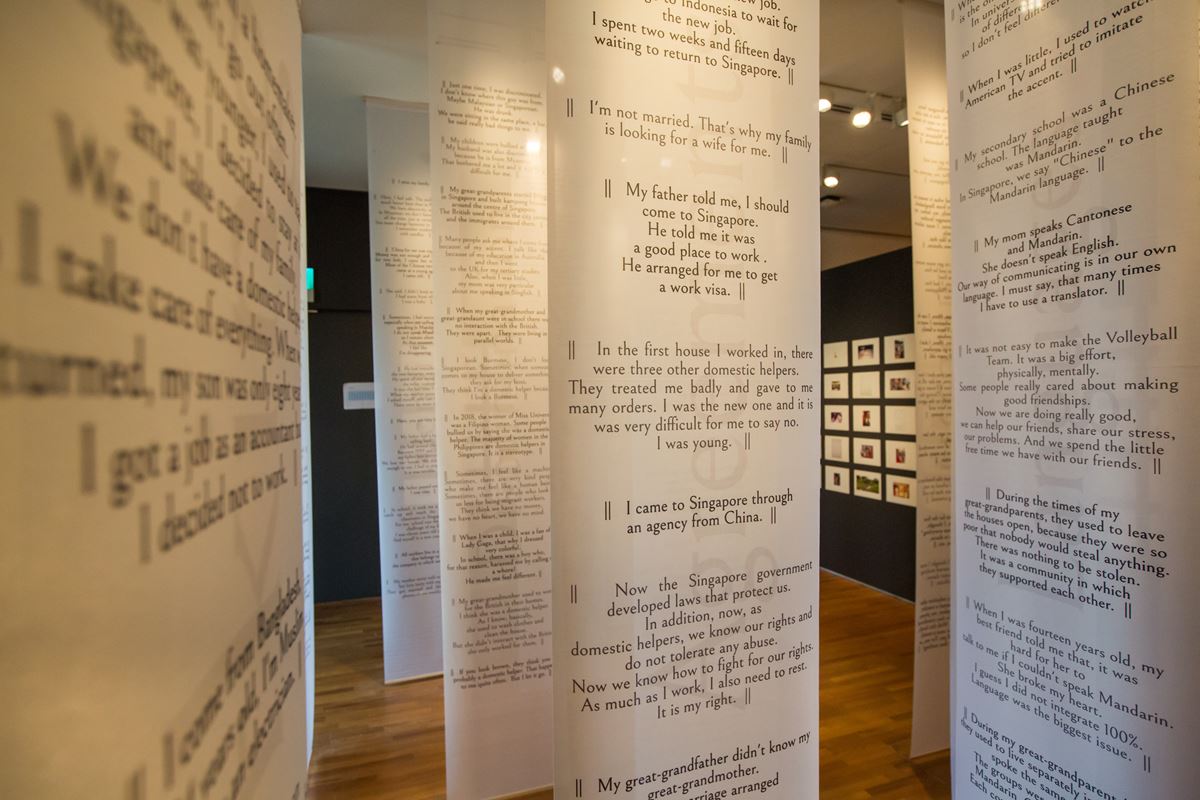

Part of this meshwork is the Coordinates section. It is imagined to be a vital node in the network of gestures that the Biennale wishes to enact as it engages with local initiatives, which in the course of time have fostered publics, communities, audiences, or other formations and assemblies. It is cast as equivalent to the exhibitionary platform of the Biennale. SB taps the vein of their efforts to amplify its own sphere of encounters and enhance more chances of meetings with people beyond the art world. The relationship with these spaces seeks to access their energy; and in a reciprocal spirit, these spaces can verisimilarly extend their scope to be part of a hopefully interdisciplinary art world and a contemporary art that is grounded in local ecologies. Coordinates focuses on three aspects of creative form: Heritage; Moving Image; and Performance.

I am working with several organizations for the Coordinates section. For instance, we are developing programs with Drama Box on participatory theater in communities, and a presentation of contemporary art as a response to an exhibition of Tamil culture and history organized by the Indian Heritage Center. We are doing this as well with an innovative tour initiative called Geylang Adventures, the International Theater Institute, and the National University of Singapore Museum. And we will have an exciting project with Projector, the cinematheque!

Various criticisms have also been levelled against the previous two editions of the Singapore Biennale (2013, 2016), both housed in the Singapore Art Museum. For example, their reliance on rehearsed tropes or clichés of Southeast Asian art, inadequate complication of curatorial narratives, and apathetic address of their entangled framework, as an international art event hosted by a local institution of regional art. How will your editions of the Singapore Biennale depart from or address these criticisms?

These criticisms are important and productive, because they reveal anxieties and tensions, and the willingness of the public to engage with the Biennale viscerally, conceptually, and so on. One way to resist the temptations of what you call “rehearsed tropes” is to resist the temptation of a theme, which for me is a form of capture, a way to reduce rather than to complexify, complicate, or render us humble in the face of the gravity of the situation and the magnitude of the prospect to change it. In the end, it helps us gain what a philosopher refers to as an “extensive clarity” as opposed to consumerist, populist simplification. SB 2019 will also revisit what it means to invoke Southeast Asia as a region, reflect on the possibilities of opening it up to a more sprawling geography and geopoetics, and not merely geopolitics. Replacing the theme is a curatorial method of selecting, commissioning, and animating artistic projects.

I appreciate your denouement of categorical inquiry, and second its paradoxical mummification and short-circuiting of its professed dialogues and advocacies. With the exponential proliferation of politicized tendencies in art, what for you is the value of the poetic, intimate, personal, or affective, and how do these seemingly infinitesimal palpitations work on a biennale’s often-grandiloquent scale?

I like the word palpitations. My mother used to have the heart condition called arrhythmia, and she would experience palpitations upon bending or positioning the body in a particular way. I remember she would just press her eyelids and the malaise would ease up. Such a process of going against the rhythm and restoring it may offer a conceptual cognate of how I want things to ramify in the Biennale. This subtle twitching of agency and contracting of structure spurs incremental insights and conversions, a foil to the conceit of the Biennale’s scale. But then again, this scale in our Biennale will be calibrated to the degree that it will be distributed across sites and gestures.

Since 2013, the Singapore Biennale has, ironically, taken place triennially, begging the question of its titular accuracy and relevance. Taking up this issue of temporal urgency (or lack thereof), what in your opinion is the persisting value or currency of the biennale format in the context of what you rightfully call our turbulent geopolitical climate?

The framework or vision for the 2019 edition of the Singapore Biennale is to foster the capacity of its location, which is Singapore in the context of Southeast Asia, to produce inspiring contemporary art and convey this energy to a more copious atmosphere of creative sensibilities around the world. Through Singapore, the region and the world come together in contemporary art. The Biennale is a productive platform to do this because it lies at the intersection of the art world, popular culture, aesthetic education, and the creative industry. Its cycle, which is every two years, is a cause for anticipation, and always strives to be current and mutating, to take risks beyond the conventional assumptions about art and the exhibition.

"The Biennale is a productive platform to do this because it lies at the intersection of the art world, popular culture, aesthetic education, and the creative industry."Patrick Flores

Biennales today struggle with the condition of the world and the condition through which the world is registered in art. It seeks to engage a more robust public beyond the art world and involves practitioners from a range of temperaments. Beyond the excitement, however, biennales also struggle with fatigue and repetition. As a response, they try to propose a different curatorial intelligence to make sense of the distribution of artists and art works, and to be more sensitive to the intricacies of both the environment of society and the material of the art. Needless to say, the discussion on what is contemporary art thickens as we speak, and the difficulty of the discourse and expression of contemporary is part of its nature. In fact, this difficulty, both aesthetically and discursively, is the enabling condition for the biennale to be able to describe a complex world of complex realities. This is why it’s still salient.

Besides providing necessary pragmatic and administrative support, why was it important for you to have a team of younger curators from the region assisting you on the biennale?

I believe that young curators should curate the biennale of their time. I value the intuition and acumen that they bring to the biennale platform. I also want this Biennale to be an occasion for institutions and the public to learn from this generation’s curators, who come from different backgrounds and regenerate the curatorial enterprise beyond exhibition making. I am glad that they are not career curators who have been exclusively schooled in curatorial programs. Rather, they are interested in a range of disciplines, and are curious about a varied repertoire of predicaments. In other words, their sympathies are broad, their archives are idiosyncratic, their experience rooted in commitments to sustained critique and reconstruction of structures; they cast a wide net in their understanding of contemporary art and its constituencies.

If you would allow a final moment of indulgence: what was a misplaced step you took (figuratively or literally; recently or in the past) in your curatorial practice that was pleasantly rewarding or gratifying?

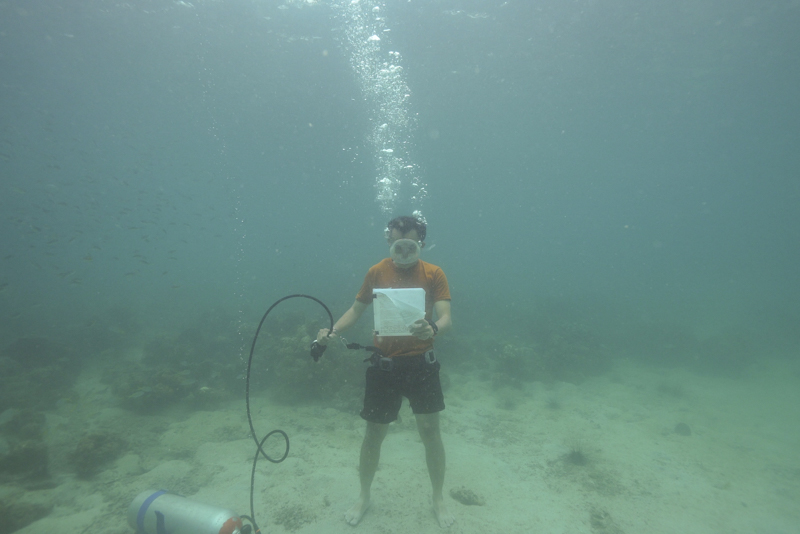

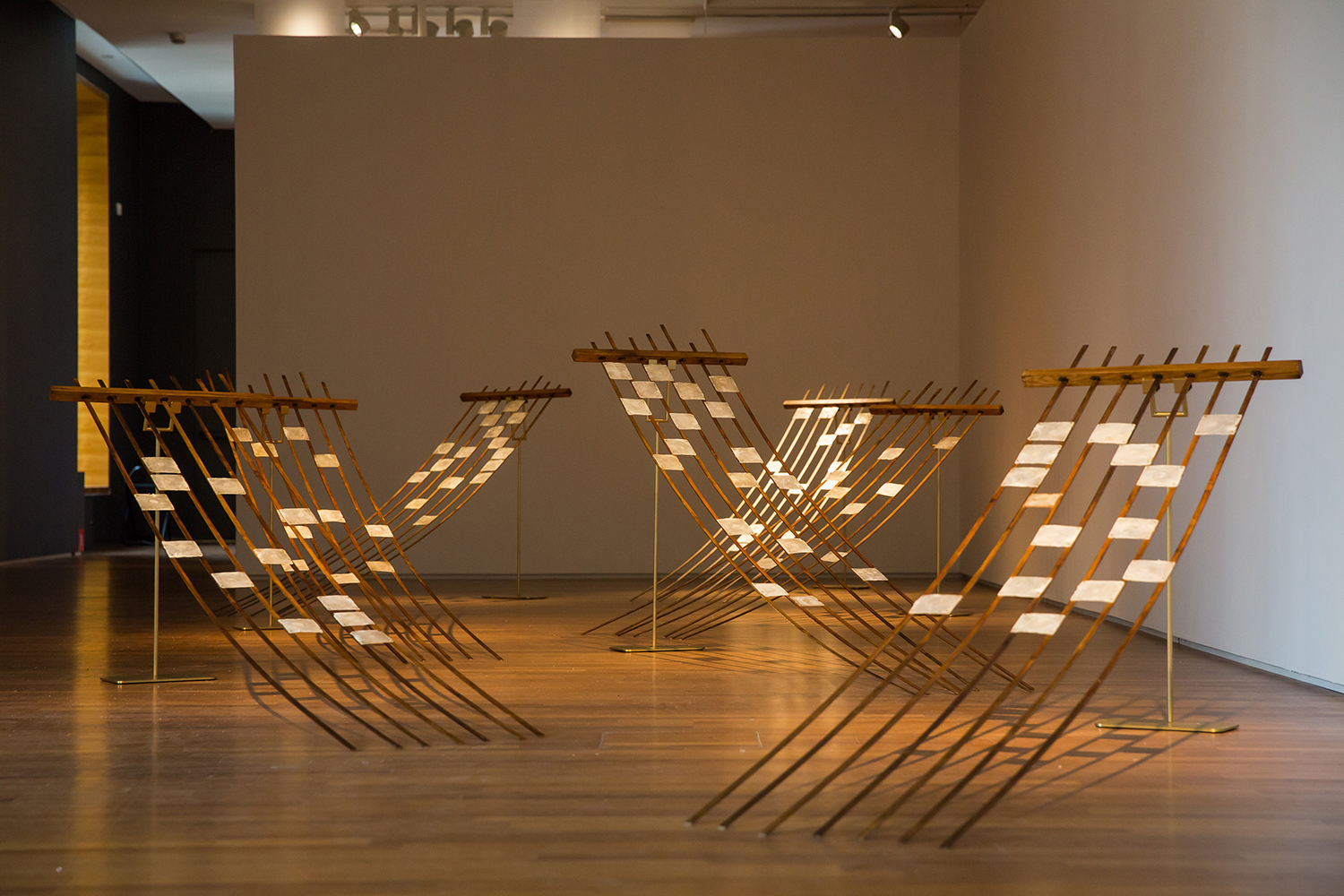

I think that the Philippine Pavilion in Venice in 2015 could have been made more tangential to the South China Sea crisis to which it responded. While I feel that the pieces already translated the reference thoughtfully, their forms could have been more open to contingency. Then again, I was constrained by the space of the exhibition and the limitations of filming in the contentious territory of the South China Sea. That being said, it was great to weigh in at an opportune time in a reflection on the implications of what remains an incendiary conflict as we speak.