Creative Destruction

by Lionel Ong

by Lionel Ong

It is not hard to see why Merriam-Webster’s word of the year for 2016 was “surreal”: with Britain’s shocking exit from the European Union and America’s stunning election of Donald Trump. In 2016, current affairs acquired a bizarre, irrational quality that bordered on slapstick—almost like a prank gone horribly wrong. When the world so perversely bucks the tide of history and repudiates the political establishment, watershed moments strike a cognitive dissonance, leaving us to question the nature of our reality. It hardly helped that both events were powered by a campaign of misinformation and a giddy barrage of false news, coming from politicians and dubious news sources alike. In a post-fact, post-truth world, where news can appear farcical, while deceptive falsehoods become readily accepted truths, “surreal” seems to best sum up the regrettably blurred lines that the world straddled the past year.

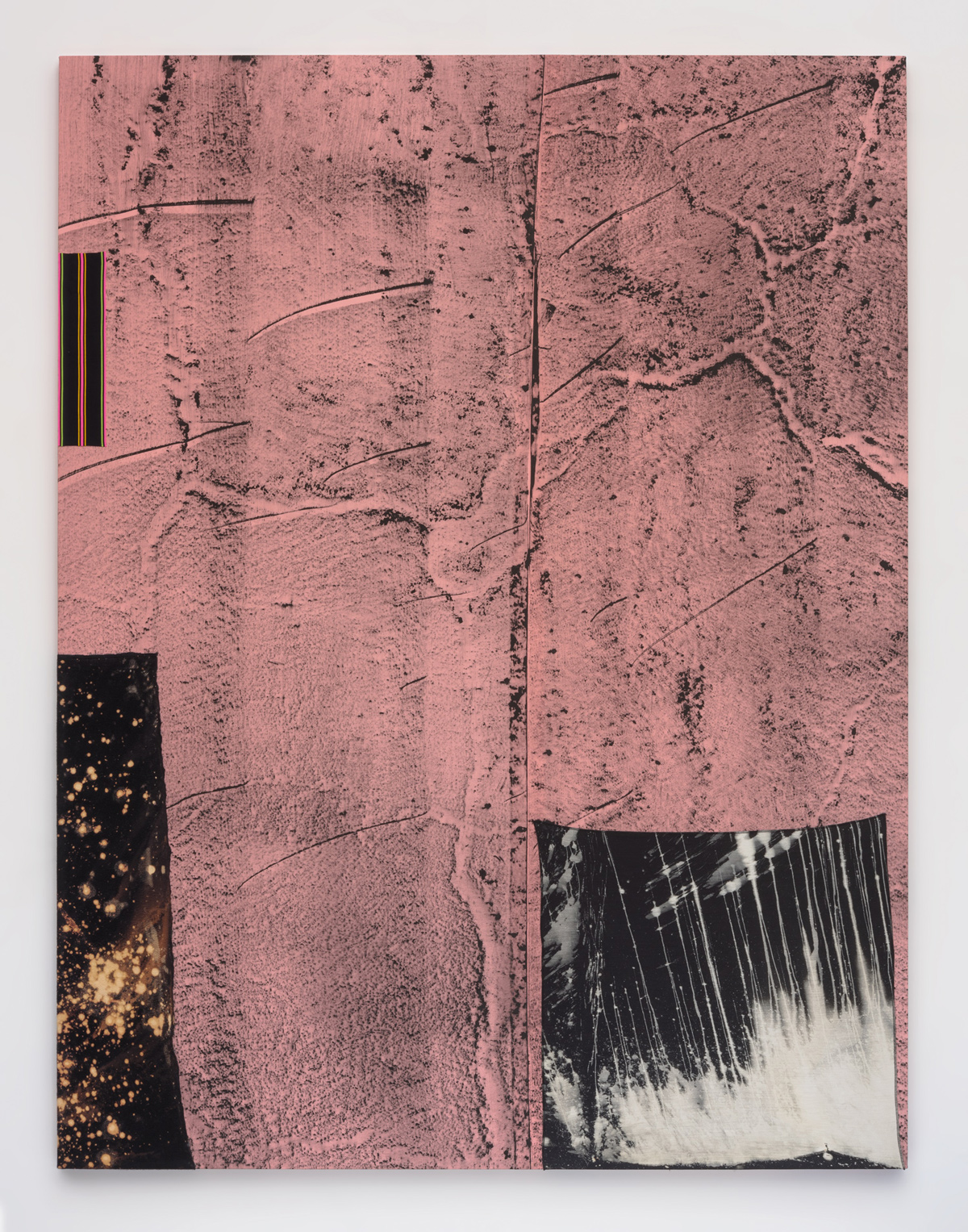

Along comes Helen Marten, the 2016 Turner Prize recipient, with her unique brand of art—employing a mix of installations, screen-printings, words, and sculptures—to construct a narrative “bound by dualism of image and language”. By constructing her works through a mishmash of objects, both found and fabricated, Marten replicates the befuddling realities of our dissonant world. In a sense, Marten’s work evokes a sort of post-internet surrealism, where not everything is ready-made and nothing appears as it seems. Marten wittingly deconstructs our ways of knowing, forcing us to reconsider our day to day consumption of facts and fiction through various media. Her works are complex, abstract and may be intimidating to many. When approaching works as academic as hers, perhaps the best entry point is to observe the quality of the materials and the ways they are individually constructed and collectively assembled.

While each individual sculpture poises out its own poetically contained narratives, Marten’s work simultaneously entails a sense of haphazard disorder that disturbs these very sensibilities. The veracity of each object and image is continuously thrown into question, leaving the viewer with the responsibility of digging beneath the surface in abstraction of latent truths. At times, this liability borders on being onerous and demanding, the ambiguity of items leaving viewers perplexed and befuddled while trying to cobble a cohesive narrative together.

Brood and Bitter Pass (2015), a cocoon-shaped structure suspended in front of a wall, is arguably one of Marten’s most recognisable works from the Turner Prize exhibition at the Tate. Fashioned out of handmade replicas and found objects, it hangs limp like a corpse, yet clean, manicured and kept together—like a cocoon, devoid of the visceral experience associated with the former. One could try a hand at detailing the complex bric-a-brac that characterises Marten’s work, but that would risk tripping over convoluted descriptions of the sculpture, finding oneself lost for words or drowning in excess of it. For the viewer, experiencing each work carries with it the interactivity of uncovering an unending chain of information and symbolism.

But this seems to be precisely Marten’s point. Describing her works as “visual riddles”, the exhibition at the Tate urges viewers to “become archaeologists of our own times”, and to explore these sculptures like a “workstation or terminal where some unknown human activity has been interrupted”. Marten’s sculptures work like a thoughtful compendium of words and associations, always allusive and never literal, thereby forming a unique syntax of its own. Found objects are spliced with precisely fabricated pseudo-objects, such as a hand-glazed ceramic disguised as a drainpipe. When pieced together into a bricolage—the organic strung to the synthetic—they sometimes read less like a smooth turn-of-the-phrase that rolls off the tongue and more like a sharp oblique reference that is difficult to pin down.

"Such visual trickery blurs the lines between real objects and objects created in their image, distorting our understanding of the sculpture the way words lead our perceptions astray."

While it may be tempting to associate Marten with the likes of Tracey Emin and Marcel Duchamp for their utilisation of mundane objects (the former famously known for presenting an un-made bed strewn with used condoms and cigarette packs, the latter known for a urinal), Marten sets herself apart by retaining a poetic sense of beauty and rejecting a nihilist approach. By incorporating a multiplicity of techniques such as blown glass, glazed ceramics and stitched fabrics to produce polished fabrications of otherwise mundane objects, Marten does not trifle herself with the drudgery of assembling items in a prosaic manner. On the contrary, she displays an impressive arsenal of techniques to challenge our perception of the world, assiduously constructing dreams-capes while maintaining a veneration for beauty.

Familiar objects are fitted into overarching grand structures, seemingly mundane items turn into meticulously handmade replicas. Such visual trickery blurs the lines between real objects and objects created in their image, distorting our understanding of the sculpture the way words lead our perceptions astray. This calls into question the way we process information, underscoring the oversaturation of images in our everyday lives. When glazed ceramic passes off as a drainpipe and carved wood so smooth and polished that it sits inconspicuously beside plastic, the materiality of the objects are inevitably thrown into the dialogue, consciously complicating the process of searching for meaning and truth.

Marten lends a haptic physicality to abstract ideas while depicting the randomness of life. Her sculptures are constructed through a seemingly random range of paraphernalia (including shoes, billiard balls, lime, egg shells, and seashells, among others); a crystallised flotsam of information and ideas that flood the world we live in, without restraining their capacity to disrupt and disturb our human desire for certainty. She beguilingly creates order out of chaos, only to intimate at the undercurrents of chaos still lying beneath the surface. This causes viewers to question the nature of knowledge and truth, or as the Tate suggests, to “consider familiar items as if we are seeing them for the first time”. Yet, we can never truly suspend our (dis)beliefs and dissociate meaning from things. By making such a seemingly innocuous request, Marten has essentially implored us to jettison our entire construct of knowledge, and with it, the way these systems have been acquired in the first place, breaking down the building blocks of information collected over years down to the minutiae.

Ultimately, one might leave with a sense of uneasiness, ideas hovering fog-like around one’s consciousness, never really settling into substance. French philosopher Rene Descartes famously spearheaded the idea that a justified belief requires perfect knowledge with the absolute absence of doubt. Yet even as we come to a level of certainty about aspects of Marten’s work, new understanding opens up new findings, and these new findings lead to new uncertainties—the viewer always closer to, but never reaching the essence of truth. Through a heady combination of items, the meaning of things are simultaneously broken down and compounded, ideas and associations never reaching finality, but rather, always remaining on the cusp of elusive conclusions and infinite ends.

Perhaps that is the point of it all. The beauty of Marten’s work lies in its koan-like qualities—in diving into Marten’s work, one can quite likely end up with more questions than answers. Yet, it is arguably in the painstaking and laborious process of abstracting ideas, rather than the ideas themselves, that we arrive at the virtue of Marten’s works. In a world where a swirl of fake news helped elect Donald Trump to presidency, Marten provides a timely rumination and reminder of our post-internet information age, reinforcing the dangers of constructing narratives with wild and treacherous certainty.