Paul McCarthy is not the only artist to have used excrement for art’s sake. Fake Sh*t (1982) was as innocuously named, an incredibly lifelike tableau of turds. Complex Sh*t (2008) propelled the American artist to international recognition. The inflatable turd was sitting in the east of eden: A garden Show at the Paul Klee Centre in Berne, Switzerland when a gust of wind blew it off its moorings.

McCarthy sold nothing until the nineties. The performance artist was “just a guy covering himself in ketchup”, a consequence of being dead broke and the result of an urge. “I had this thing about exposing the interior of the body,” he explained “the orifices leading into the body, and what the interior was, and the taboos of the interior.”

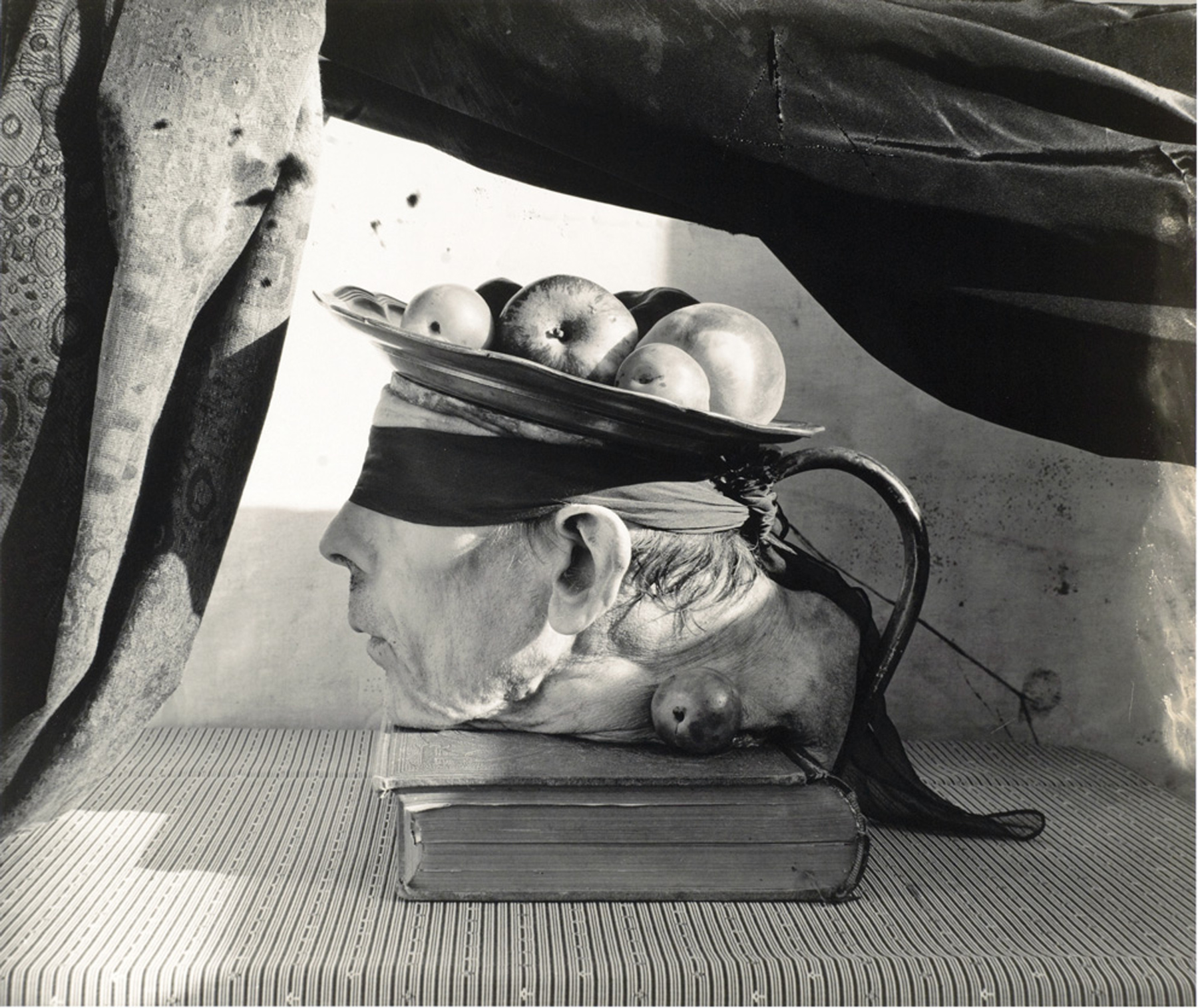

This, dabbling in bodily emissions was de rigueur. The famous ones took it literally. Andres Serrano dropped a crucifix in his own urine in 1989. Half a decade later, Marc Quinn cast his own head in blood (also his own). Noritoshi Hirakawa took it live: in The Home-Coming of Navel Strings at the 2004 London Frieze Art Fair, a woman took a daily dump after reading a novel. Helen Chadwick’s Piss Flowers (1991/1992) were bronze sculptures cast from cavities made when urinating in the snow by her and husband David Notarius.

It seemed like the art world was dredging dangerously deep until its peak in 1999, when Tracey Emin won the Turner Prize for showing them off in My Bed. Condoms and other daily detritus joined menstrual blood-stained knickers. This marked the triumph of the British Young Artists (BYAs). Shock art works, apparently.

The public drank it up. It was a redefinition of art on the brink of a new millennium—post-modernism was on.

Grappling with the rise of shit in art; Brit Craig Brown captured it in his equally iconic essay My Turd when he said:

“My Turd has a lot to say about birth and death, a lot to say about the nature of self, a lot to say about the whole process of defecation and renewal in contemporary society, and it has a hell of a lot to say about art itself.

It is almost as if, in some extraordinary way, the artist were asking us to confront the very nature of what we call 'shit'.

What is it? Where is it? Who will buy it?”

Art’s enfant terrible Damien Hirst recently enthused, rather late to the game, about his long-standing drive to make “the most perfect poo you could make in bronze”. “So one minute if you did it in the toilet you would want to go and tell your friends about it, it’s like so healthy and perfect, and then put it outside somewhere, and I was going to call it ‘Untitled’ and in brackets ‘(Number 2)’”.

Let’s rewind.

Desperately seeking salvation

Around the 20th century, lofty aspiration and refinement became passé. Art, always the avant-garde of society, sprung loose. The Dadaists marked the seed of a change in popular direction. In fact, Marcel Duchamp brought the poo barrier down with Fountain (1917). The upside down urinal stared us in the face; and we imagined it brought us closer to the innards of ourselves, however banal. The porcelain display was certainly open for interpretation. Its conceptual challenges pushed us to its visceral extreme. By the fifties, life-affirming Impressionism and coiffed anything faded fast in the aftermath of World War Two, re-industrialisation and McCarthyism (the politics, not the artist). They exist now only as boxed fantasies in Mad Men. The world had given up the last of its idealism by the Vietnam War. Even the hippies could no longer believe their own smoke.

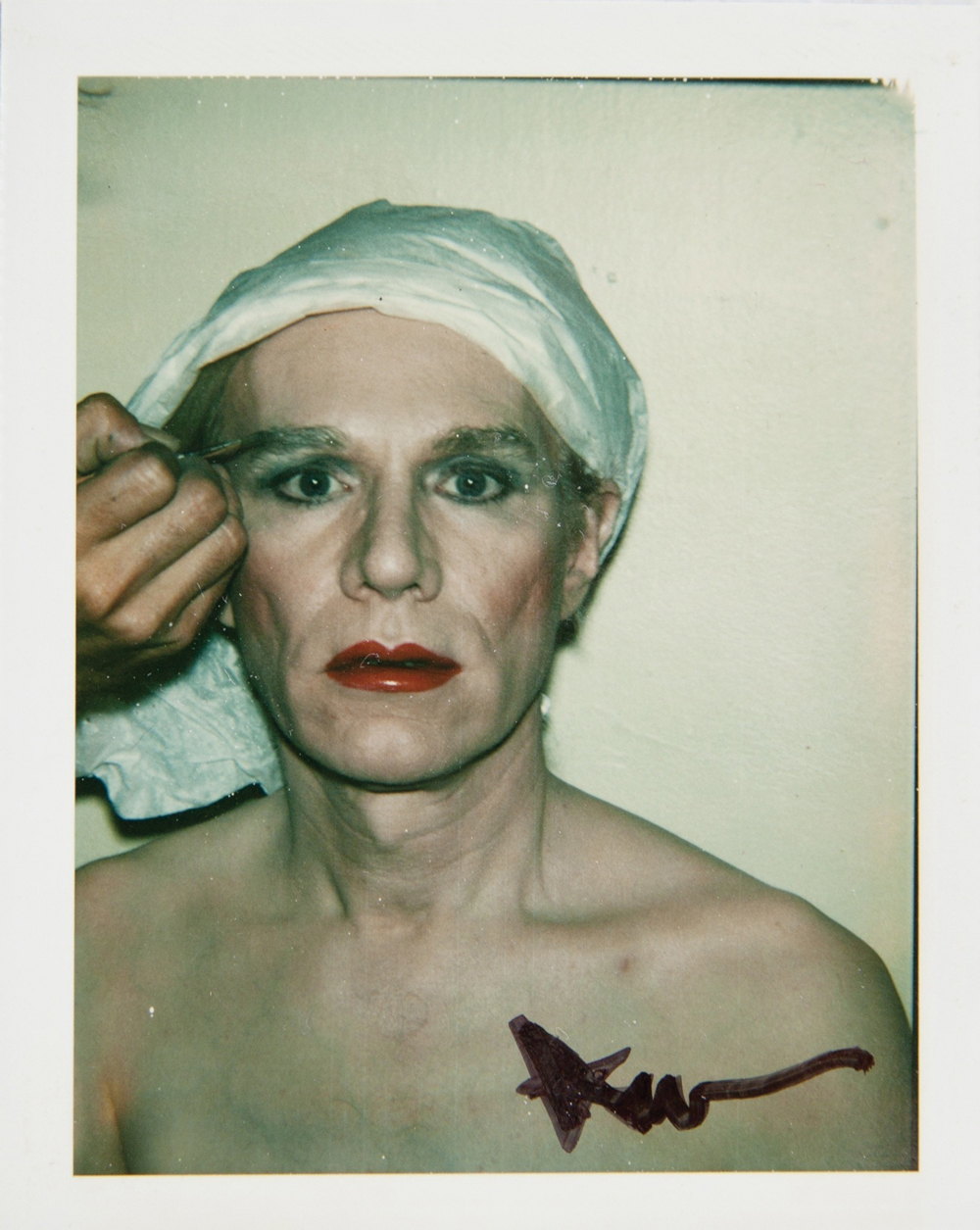

Serrano, Quinn, Hirakawa, and Chadwick were born of these ashes. East of the Atlantic, the YBAs would cement their reputation as conceptual artists who focused on the darker aspects of contemporary living. To be avant-garde was to dissect, be clinical, or delve into the abysmal hollows of psychology. Celebrity status was ensured, if you could combine all three. Charles Saatchi even designed a special room to keep Tracey Emin’s bed.

This brand of existential play with physicality and identity is not new. When Piero Manzoni produced ninety cans of Artist’s Shit (Merda d’artista, 1961), he was asking a personal question. He was also echoing a contemporary dilemma that would plague his successors. Each can held thirty grams of faeces, labelled in label in Italian, English, French, and German. It was “the perfect metaphor for the bodied an disembodied nature of artistic labour”, as artist and critic Jon Thompson called it.

Hirst closes the loop for us. “Art goes on in your head. If you said something interesting, that might be a title for a work of art and I’d write it down. Art comes from everywhere.” The golden liner: “It’s your response to your surroundings.” Shit in art is a manifestation of an artistic cogito ergo sum. It is also a perfect blank canvas for projecting dissatisfaction, and on its back, all ills from anger to hopelessness to indifference and impotence. It is no wonder Manzoni drank himself to death by the age of thirty.

A rose by any other name

Of course, faecal matter is not the only carrier of such sentiment. But look at the rage that could be evoked by a piece of art deemed too polluted.

When Marcus Harvey exhibited his painting Myra in 1997, the public revolted. Windows were smashed; eggs thrown; careers within the Royal Academy given up. Myra had to be placed behind Perspex glass and guarded by security. No one could deal with it. Even its protagonist, mass child murderer Myra Hindley herself wrote a plea through the Guardian to remove the painting. With the extent of media saturation and volatile public opinion, Harvey became vilified alongside Hindley. Surely the artist knew it was bound to cause controversy. He did not. “I just thought that the handprint was one of the most dignified images that I could find. The most simple image of innocence absorbed in all that pain.” Articulating the underbelly evoked further repulsion, erasing any hope for illumination, as The Times art critic Richard Cork explained, “Hindley’s face looms at us like an apparition. By the time we get close enough to realise that it is splattered with children’s handprints, the sense of menace becomes overwhelming.”

If we miss the humanism stirred in those sentiments, then what remains? No pun intended, shit becomes the final dissolution of all that could potentially have been good or inspiring, unless, of course, perversions allow otherwise. Even so, that only invites other questions, such as redefining perversions. Welcome back to the dilemma of definition, circa 1917.

Meanwhile, it is in our nature to dig, scrapping the bottom of the barrel and hoping to hit pay dirt; it is the nature of boundaries to entice. One last question remains: what makes a man go there?