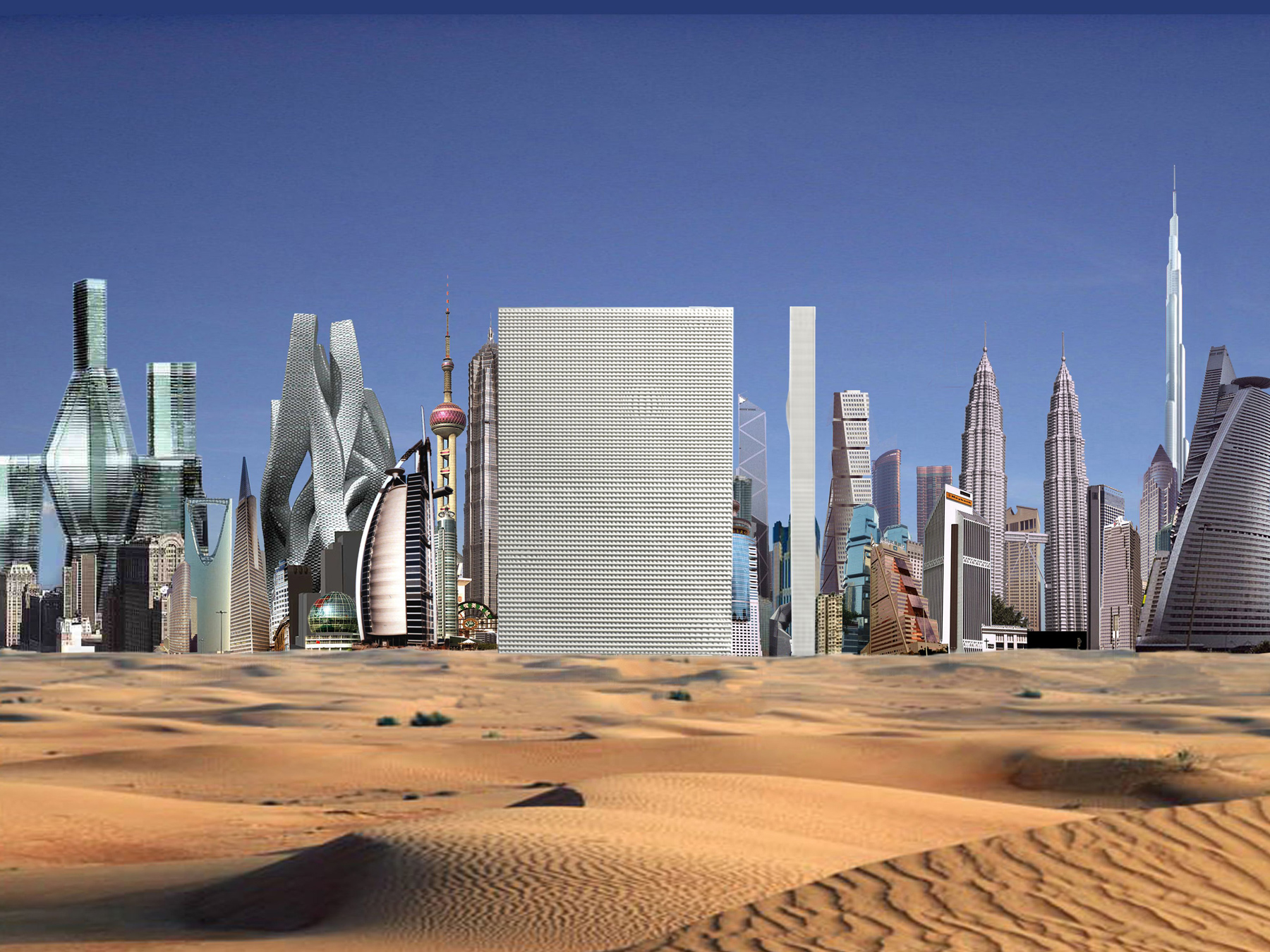

The phenomenal progress of globalisation and the attendant flow of capital, labour, and information has borne witness to unprecedented modernization and a rapid exchange of ideas. On the cultural front, this has heralded a phenomenal consilience in the traditional binaries of the occidental and the oriental, blurring the lines between East and West, and redefining the paradigmatic ways in which we understand culture in the context of a modern contemporary city.

Through a candid discussion of their architectural and cultural projects, world- renowned architect Rem Koolhaas (RK) and prominent cultural advisor Michael Schindhelm (MS) explore the ways in which globalization and modernization have impacted architecture, as well as arts and culture on a broader level. By tapping into Schindhelm’s experience in the Middle East and Koolhaas' experience in Asia, the conversation provides an eclectic mix of views, providing an analysis of the transformation of urban landscapes and mapping the way forward for the modern cities of our time.

"...what happens in Asia ends up affecting the West. This whole sentiment that the West is somehow leading is a view that has become completely misplaced."Rem Koolhaas

MS: When Rem and I met for the first time almost 10 years ago, we bumped into each other in the office of the Mayor of Amman, Jordan. At that time, the Mayor was about to launch a big cultural project, which was supposed to turn a tobacco factory into a theatre. Like so many other projects at that time, it never materialized. However, we became friends, and we started working together. At that time, I was already working in Dubai which was where we started meeting more often. Closer to that timeline, Abu Dhabi had announced its projects in the Saadiyat Island with the new Guggenheim and the Louvre. There were similar projects in Dubai. Doha had just opened an Islamic museum; there was the Esplanade in Singapore; later the West Kowloon Cultural District came up in Hong Kong; and Beijing had just opened the National Opera House close to Tiananmen Square, and started to refurbish the National Museum.

There were many new projects coming up in an unprecedented way in these emerging countries, particularly in Asia, and in the Middle East, and often architects like yourself were approached to design museums, performing arts centres, libraries and concert halls etc. If you look back at this decade, what do you think about this time today?

RK: Personally, it was an exciting but ambiguous period because, as architects, we had incredible opportunities to help define major cultural facilities in countries that we were somewhat familiar with, but did not know well. And of course inherently, it also required a fundamental modesty on our part, because how can you bring ‘culture’ if you simply bring what the West considers to be culture? So I tried to use this period not so much to confidently say what culture should be, but to explore. That was where people like you who were on the same wavelength came in, to explore what might have been relevant interventions or contributions to emerging cultural patterns, sensibilities, politics and possibilities in Asia. It was both a great opportunity and something that we approached with great modesty, which we considered to be a learning experience.

MS: So of course that provokes the question: What have you learned? What has become different for you in the practice of an architect in this process?

RK: From the beginning, I think we have both maybe underestimated the enormous influence of the economy on culture, and how particularly in Asia and the Middle East, economic thinking or money is an integral part of any consideration of culture. We are fundamentally not used to that combination, and have tried to navigate that combination as it emerged. For example, West Kowloon started with a government which was adamant that the combination of culture and money would not happen. It was extremely explicit that it was not a safe kind of cultural project, but actually dedicated to experiment. What you saw in the meantime was that money and developers played a major role. It’s still an open question for me whether we were too naïve and too idealistic, or whether for the time being we had no choice but to be idealistic because that was maybe the most powerful thing we could inject.

MS: I think resilience was also very necessary. If you walked away with the first conflict you would never have achieved anything. You achieved quite a bit, apart from the fact that there was this fluency, things were a bit hard to grasp because they were changing fast, and decision-making was difficult. However, you managed to create one of the most important buildings in Beijing, the CCTV tower. In this case, it was not so much about private money but a complicated government you had to deal with. Can you share with us some major elements of your experience?

RK: I’ve believed for a long time—that is of course not exactly the same everywhere—that the major effect of the market economy has been to separate architects from the public good. It used to be the case that we worked for public bodies which was assumed that had the interest of mankind in mind. But in the last 30 years, that connection has almost been completely cut and therefore, architects more typically serve the interest of developers. That means money is very important.

Nevertheless, we have maintained that interest in working for the public sector, and so I see the CCTV project as an example and prototype of that. Maybe I should also mention our interest in the Japanese Metabolists, about whom I recently published a book. Metabolism is a movement consisting of Japanese architects who were very active in the '60s, connected to architects like Isozaki and later Toyo Ito. These are architects who had a huge impact and influence on Singapore in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Metabolism was an instance where the Japanese state was systematically provoking ideas from architects, and it was dedicated to modernizing Japan in its entirety, making the country less vulnerable to earthquakes and floods, and to decentralization to relieve the burden on Tokyo. So for me, that was a prototype of a state having a degree of imagination in mobilizing architects to work for the good of the entire country.

You could say that was what I’ve always been looking for and that is what I felt from the Chinese state at that point in 2001, which was the same year as 9/11. If you talk about recent experience in Asia, you think about the TPAC (Taipei Performing Arts Centre) in Taipei, which we are about to complete. The TPAC is a combination of three theatres, and it tries to radically rethink what a theatre can be. It is also a building for the state. So, there has always been nervousness about how influential money has become.

MS: When I was working in Dubai to set up the Authority for Culture and Arts, which was a kind of ministry of the Emirates of Dubai, I learnt that the government is actually also a private enterprise. Thus, the order between public and private was completely blurred, like so many other principalities in the gulf. In this sense, you’ve paradoxically dealt with a government but also actually dealt with a private business. Sometimes, it’s difficult to explain to decision-makers that setting up a gallery or maybe an opera house is fundamentally different from setting up a shopping mall or a hotel. In China we see a blurring of borders between public and private, and even more so in Hong Kong. From a Western perspective, how much of the term ‘public’ can you really apply to those efforts?

RK: We should be careful not to discuss Asia as an exception. This blurring between public and private that you are talking about is also increasingly present in Europe. Asia is not in an exceptional situation that needs to be brought up to Western or European standards; rather, what happens in Asia ends up affecting the West. This whole sentiment that the West is somehow leading is a view that has become completely misplaced. In the last 20 years, the lead of the West has been replaced by at least an interaction or mutual influence between the two, and at most an influence of the East on the West.

MS: I often disappointed my decision-makers when presenting cultural projects because we had to explain that once the buildings have been delivered, and we started operations, it would not make revenue any time soon because those buildings are built in order to create other types of commercial values. You are completely right that we face those issues in the West, but until ten years ago it was still something new even in this regard. I wonder if you think that this is temporary because the question is, if there is a shift from public to private, is this something that will affect our understanding of culture?

RK: Everything is temporary of course. We must therefore avoid being disappointed, and really investigate and participate in the transformations taking place, which we would otherwise have to abstain from with a mixture of arrogance and bitterness. So I’m dedicated to following all these recent events as a critical participant. I think that is for me, a very satisfying way of being engaged—knowing that we don’t live in a perfect world. We also see with our eyes, in real time, the emergence of new combinations, practices, sources of energy or of intelligence. And I think for instance, art fairs are one of those instances where you can be skeptical of the financial incentive. But if the organizers of these events are increasingly part of it, it creates a new type of cultural interaction that I really welcome. So I think it is possible to participate in an idealistic way in events that you don’t completely endorse.

MS: That is only the case if you stay idealistic in the process. I think what we both share is that we are both still participating in these projects. This means we have not lost our idealism about making something happen. Is that correct?

RK: That is correct but we shouldn’t sit around to 'wait and see' because it also requires effort to 'make it happen'.

MS: Sure, but you need somebody to make it happen. We have to try hard and that is our daily experience, to engage despite our experiences in one or another. Of course, we were criticized for working with non-democratic leaders and many of these projects were so called top-down projects. Critics would usually say that those projects would never open up to society because they were top-down projects. What is your opinion of this and how do you see it today?

RK: It’s an inevitable criticism but we have chosen our battles. We were actively criticized for our participation in CCTV. In German newspapers, we were criticized for working with dictatorships, or faced with criticism that in China you could do hospitals or social housing, or at the most, some cultural buildings but never do something for the state. My intimate conviction remains that whatever happens in China is incredibly crucial for the wellbeing of the world. Therefore, it’s a good thing to participate in controversial or maybe dangerous elements, because only by engaging on that level would there be hope of any kind of real interaction or effect. Of course, what the world doesn’t see is all the work we didn’t do for enterprises we didn’t believe in, or for countries we thought were not evolving in a more desirable way.

MS: The CCTV tower is the symbol for information because it is built for state-owned TV stations. How did you try to support this notion of the flow of information in a country like China in terms of design?

RK: I’m not sure if I was able to symbolize the flow of information because it is quite difficult to symbolize flow. There was one way in which I believe we really introduced something radical and new in China. The Chinese state is interested in stability and in a kind of self-evident and powerful image. One of the inherent qualities of CCTV is that it is a building that is completely unstable. It does not look the same from any direction. It is a building that looks powerful from certain angles but also sometimes weak and even awkward. I think we were at least able to introduce a very challenging presence that played with the most fundamental expectations of the Chinese state in the heart of Beijing and made it, to some extent, even an emblem of Beijing.

MS: As you know, during the time you were building the CCTV tower, I was shooting [a film] about the making of the Olympic Stadium in the same city. They had invited Ai Wei Wei at that time to support and provide a design that responded to Chinese reality. Do you try to do this sometime also? To engage with local artists or experts?

RK: I would say my entire professional life has been a systematic search for collaborators. There is not a single work that I’m proud of that has not been inspired by, influenced by, or determinedly defined by balanced collaborations. For instance: my collaboration with the Sri Lankan engineer, Cecil Balmond on structural aspects of my projects. I had a lot of interests that I pursued before I was in the position to actually build in China. Even 10 years before, we were already thinking about participating in a competition there. I had a group of three or four intimate friends and collaborators that came together to speculate on the direction of China, the importance of China and what we could do there. Somebody like Qingyun Ma, who is now Dean of USC (University of Southern California) in America, but was also a very important emerging architect in China, played a big role not so much aesthetically but in the negotiation and in the navigation of Chinese culture. If there is one position I really hate and never would want to be in, it is to be an expat doing expat things in foreign countries.

MS: You actually grew up in the region—you were eight when you came to Indonesia with your family and lived for four years here. You never really worked here as far as I know, but you didn’t lose the interest. There is also a publication that you issued almost twenty years ago under the title Singapore Songlines, in which you looked at the city. Looking back at the Singapore of 1995, what has changed not only in Singapore but also in your perception of the city?

RK: In 1994, I was planning a book which was supposed to be called The Contemporary City. I thought the terms in which cities were described were hopelessly useless, in terms of the urban developments that were most radical, most acute and most intense in the world at the time. In other words, we had a vocabulary that was entirely Western, which was about boulevards, plazas and other compositional entities. It was clear that in Asia, cities were evolving according to entirely different principles at an incredible speed, a speed that had never happened before. So I felt I had to do a book about a specific number of cities, to reinvent the vocabulary of cities as they were rather than as they should be.

I wanted to write about Tokyo, Beijing, and Singapore. I wrote about Singapore because it was perhaps the most radical example of any of these situations. The entire island had been conceived almost as a project and also as a work of art—at least a political work of art, where every single aspect was redefined in a very short period of time by a regime that had enormous competence in organizing and executing its intentions.

The desire to understand an environment that was generated according to these new principles, to see and experience how it feels, was my motivation in going to Singapore. I was also interested in the result of cities being built by regimes that, by Western standards at the time, would not be called democratic. The article is an investigation of all those factors at the same time. I was trying to be precise rather than critical, but hopefully without the typical condescension that was de rigueur when talking about the city at that time.

MS: I reread the article recently for this event. You have statements like “The ‘Western’ is no longer our exclusive domain.” Could you elaborate on this?

RK: You could say that after the Enlightenment, the West launched a series of values, techniques, and apparatuses like the microscope and the camera, all of which define our contemporary world. We ironically consider these inventions Western, but they have become so universal, so ubiquitous and so inevitable that I think it is absurd that we maintain a sense of copyright over them. Their dissemination and success make them universal. Given the fact that we in Europe barely build any cities anymore, the whole idea of the modern city is now, for me, not a Western idea but simply an Eastern idea that is being defined by the East on its own terms. Whether we want to admit it, that is the new reality. The statement you quoted was also announcing a kind of modesty or at least an irritation with our own continuous sense of centrality in a culture which has become global and ubiquitous. If we endorse globalisation, this is the result, and part of that is that we have become a lot less important.

MS: You were obviously trying to find out if there was a new society or a new social model emerging in Singapore. Twenty years later, do you think that was true? And how does this relate to our social models, and again the Western model?

RK: Maybe we should for the time being stop the comparison. If you talk about a new society, I’m reluctant to act as somebody who can comment and judge whether a new society has emerged in the past 20 years. There is an enormous amount of development and invention that in any case make global societies completely different from what they were in 1995. Yes, I do see an evolution and an emancipation of the Singaporean civilization. But I also see a greater effect of homogenization through inventions like the Internet and the mobile phone that has already created a global generation. This will appear here in starker forms than in Western societies, but it is still the same phenomenon.

MS: You also wrote: “Singapore stands out as a highly efficient alternative to a landscape of almost universal pessimism.” How do you see this today?

RK: I would say that is still very true. I have not met a single pessimistic government representative here in Singapore. Singapore has an enormous belief in making things and changing things deliberately, which creates fragility here and there. That fragility is, in certain cases, paralleled with an interest in shifting some decision-making to larger parts of the population.

MS: You also wrote in Singapore Songlines that “the next round of Eastern-Western tension is whether democracy promotes or erodes social stability”. In the meantime, social stability is quite obviously in decay in many Western countries—people are disgusted in our governments, and political innovation is barely existent in relation to economic change. How do you see this in Asia?

RK: Part of the 2014 Architecture Biennale in Venice was an exhibition called Elements of Architecture. There we looked at the history of architectural elements such as ceilings, walls, floors, windows. People were initially mystified by the banality of such an effort, but what we were able to show was, after thousands of years of more or less stable existence, almost every single one of these architectural elements is being modified in very serious ways by modern technologies.

Sensors have entered architectural elements, such as floors that record if people have fallen down and can alert the authorities. There are toilets that analyze every event in detail and report on them and in certain circumstances, report directly to your doctor. There are sensors embedded in every car that collect and contain data. In certain cases, you pay less insurance if you let the insurance company record and read your data so that you can show them that you never misbehave.

These mutations are typically sold in terms of how you can make your life more comfortable and safer even to the point where cars are auto-piloted. So what I see at the same time is a decay not of democracy, but of the possible range of risk-taking and adventure you can take in a democracy. That seems to be the platform where East and West are meeting, a platform where we avoid sensitivities and respect each other. This is a collective political correctness, which is exactly where authoritarian and democratic regimes meet.

MS: You actually grew up in the region—you were eight when you came to Indonesia with your family and lived for four years here. You never really worked here as far as I know, but you didn’t lose the interest. There is also a publication that you issued almost twenty years ago under the title Singapore Songlines, in which you looked at the city. Looking back at the Singapore of 1995, what has changed not only in Singapore but also in your perception of the city?

RK: In 1994, I was planning a book which was supposed to be called The Contemporary City. I thought the terms in which cities were described were hopelessly useless, in terms of the urban developments that were most radical, most acute and most intense in the world at the time. In other words, we had a vocabulary that was entirely Western, which was about boulevards, plazas and other compositional entities. It was clear that in Asia, cities were evolving according to entirely different principles at an incredible speed, a speed that had never happened before. So I felt I had to do a book about a specific number of cities, to reinvent the vocabulary of cities as they were rather than as they should be.

I wanted to write about Tokyo, Beijing, and Singapore. I wrote about Singapore because it was perhaps the most radical example of any of these situations. The entire island had been conceived almost as a project and also as a work of art—at least a political work of art, where every single aspect was redefined in a very short period of time by a regime that had enormous competence in organizing and executing its intentions.

The desire to understand an environment that was generated according to these new principles, to see and experience how it feels, was my motivation in going to Singapore. I was also interested in the result of cities being built by regimes that, by Western standards at the time, would not be called democratic. The article is an investigation of all those factors at the same time. I was trying to be precise rather than critical, but hopefully without the typical condescension that was de rigueur when talking about the city at that time.

MS: I reread the article recently for this event. You have statements like “The ‘Western’ is no longer our exclusive domain.” Could you elaborate on this?

RK: You could say that after the Enlightenment, the West launched a series of values, techniques, and apparatuses like the microscope and the camera, all of which define our contemporary world. We ironically consider these inventions Western, but they have become so universal, so ubiquitous and so inevitable that I think it is absurd that we maintain a sense of copyright over them. Their dissemination and success make them universal. Given the fact that we in Europe barely build any cities anymore, the whole idea of the modern city is now, for me, not a Western idea but simply an Eastern idea that is being defined by the East on its own terms. Whether we want to admit it, that is the new reality. The statement you quoted was also announcing a kind of modesty or at least an irritation with our own continuous sense of centrality in a culture which has become global and ubiquitous. If we endorse globalisation, this is the result, and part of that is that we have become a lot less important.

MS: You were obviously trying to find out if there was a new society or a new social model emerging in Singapore. Twenty years later, do you think that was true? And how does this relate to our social models, and again the Western model?

RK: Maybe we should for the time being stop the comparison. If you talk about a new society, I’m reluctant to act as somebody who can comment and judge whether a new society has emerged in the past 20 years. There is an enormous amount of development and invention that in any case make global societies completely different from what they were in 1995. Yes, I do see an evolution and an emancipation of the Singaporean civilization. But I also see a greater effect of homogenization through inventions like the Internet and the mobile phone that has already created a global generation. This will appear here in starker forms than in Western societies, but it is still the same phenomenon.

MS: You also wrote: “Singapore stands out as a highly efficient alternative to a landscape of almost universal pessimism.” How do you see this today?

RK: I would say that is still very true. I have not met a single pessimistic government representative here in Singapore. Singapore has an enormous belief in making things and changing things deliberately, which creates fragility here and there. That fragility is, in certain cases, paralleled with an interest in shifting some decision-making to larger parts of the population.

MS: You also wrote in Singapore Songlines that “the next round of Eastern-Western tension is whether democracy promotes or erodes social stability”. In the meantime, social stability is quite obviously in decay in many Western countries—people are disgusted in our governments, and political innovation is barely existent in relation to economic change. How do you see this in Asia?

RK: Part of the 2014 Architecture Biennale in Venice was an exhibition called Elements of Architecture. There we looked at the history of architectural elements such as ceilings, walls, floors, windows. People were initially mystified by the banality of such an effort, but what we were able to show was, after thousands of years of more or less stable existence, almost every single one of these architectural elements is being modified in very serious ways by modern technologies.

Sensors have entered architectural elements, such as floors that record if people have fallen down and can alert the authorities. There are toilets that analyze every event in detail and report on them and in certain circumstances, report directly to your doctor. There are sensors embedded in every car that collect and contain data. In certain cases, you pay less insurance if you let the insurance company record and read your data so that you can show them that you never misbehave.

These mutations are typically sold in terms of how you can make your life more comfortable and safer even to the point where cars are auto-piloted. So what I see at the same time is a decay not of democracy, but of the possible range of risk-taking and adventure you can take in a democracy. That seems to be the platform where East and West are meeting, a platform where we avoid sensitivities and respect each other. This is a collective political correctness, which is exactly where authoritarian and democratic regimes meet.

MS: I think now is a good time to include the audience. I would just like to say that I’ve been here for a week talking to artists and art professionals and I got to hear this issue again and again. I share your opinion. And of course, globalization has changed our understanding of security and freedom, and we probably have to negotiate it. It is a question, always, of how society allows it to renegotiate.

I wanted to ask about the notion of nature and the natural and how we should go about thinking about that in the urban condition today. I remember reading something that you wrote which said that there was nothing natural about Singapore. Our cities are getting very large, so there is a tension between architecture and what is natural. How would you advise us on thinking about that notion of nature?

RK: When I wrote that there is nothing natural about Singapore, it was not a kind of provocation. I was simply documenting the transformation of the island where all the mountains and the hills had been flattened. And some of the earth was used to expand the coastland. There was nothing condescending or personally critical about it. The thing about Singapore is that yes, it is growing but it cannot grow beyond its footprint. You don’t know how lucky you are because at least that confronts you on a daily basis—this idea of who you are—and therefore that makes it vivid, with regard to what should be the next step, or the next iteration. I think there is now a real focus on nature in Singapore. To some extent, I understand it completely. But the irony is that because nature has been eliminated almost entirely, it is now typically brought back as a memory, or in terms of what was once there. The fate of Singapore is not to go back, but to proceed and therefore to find a less nostalgic attitude to nature. It is simply to see where nature or other incorporations of nature could be different and perhaps begin to develop more artificial ways of looking at nature or introducing nature. In other words, nature is not natural anymore. For a real experience of nature you need to travel, which is of course not very natural. On the other hand we will never be able to bring it back to the kind of situation we once had.

We have spent a lot of time talking about the past and I have a question regarding the future. As we all know, technology has profoundly changed every aspect of our lives—the way we socialize, artificial intelligence, drones, automatic cars, etc. I wonder if there is anything in the tech space that excites and fascinates you, or impacts your vision of architecture in the future?

RK: For the past four or five years we have been looking at the countryside, not in terms of what remains, how it was, as a counter to the city, or as a kind of a picturesque terrain. On the contrary, it is becoming clearer that the countryside needs to accommodate all the infrastructure, storage and scale of production that the enormous growth of cities need. If you go to certain parts of America, Holland, or surely Singapore, you’ll see the emergence of an entirely new typology of architecture. You will see that there are enormous entities, sometimes two by three kilometres in a single building, completely filled with processes with barely any human inhabitation. In certain areas of the world they come together at the scale of cities, but paradoxically, the cities are mostly inhabited by a few maintenance people, a lot of robots and otherwise mechanized processes. But still it is architecture because it is conditioned, it is enclosed and it has features of architectures in terms of floors, roofs, etc.

Those kinds of new environments are the next level that we want to not only understand but also to engage with; exploring the kinds of environments where those automated processes flourish. If you then imagine what kind of architecture that would be, for me the most exciting idea is to get rid of the colour beige. Beige is the colour of consensus, of an ultimately non-offensive environment, which you are surrounded by all the time.

You often mention the changing position of the architect. I would like to ask a question about the changing position of the architect in the wake of an increased emphasis on the virtual space rather than the urban. How do you see the importance of virtual space increasing? And is this creating a negligence of the urban space?

RK (to MS): I think the question on virtual space is something that you’ve actually discussed in Russia and I think that that is a very significant question.

MS: But I of course have no answer. On the one hand, I’m one of those old people in Europe who still deal with the culture and arts, so I’m not from the digital age. However, it is true that I’m also talking to younger people who are using the Internet and social media. Of course we know how much this has changed our practice everywhere, including in culture and arts, there is no question about this. I must also admit that when I started working outside of Europe it became much more important. As Rem has mentioned, in many emerging cities you have to embrace communication in a society which is younger. Somebody told me yesterday that he had just came back form Phnom Penh, where the average age of the population is around 24. When I was working at Dubai the average age was 27, most of my collaborators were the age of my children. So yes, the practice changes and therefore so does the perception of reality. But what that means in terms of culture and arts is hard to say. I don’t dare to make any predictions on architecture.

What really changes is the means of communication. When I was working in the Middle East and the Far East on cultural projects there was on the one hand always architecture involved because there were no buildings where there were no institutions. So we had to invite architects for competitions, to make proposals on what kind of building is required. More importantly, we had to think about the operations of these buildings, and we had to think about these operations under the condition of the growing importance of new tools and technologies, which are changing the way culture and arts are produced and consumed today. For example, publishing in the Middle East started as online publishing, and I noticed a similar experience later in China. Sometimes censorship is a reason why some traditional forms of cultural production would not work, but in the Internet and social media you can still create this type of production.

That is why I would say in countries where there is no traditional landscape of culture and arts, there is a great opportunity for developing new forms and outlets of producing and consuming culture and arts. I must say, as a writer and film-maker, the traditional form of producing films and books is fading away. Even in rather stable countries like Germany the landscape of publishing has totally changed, I could even say some major publishers have vanished and are not really replaced by something comparable. So you have to go into technology and tools to rethink the way you work. When I’m talking to artists in Asia, every artist is very savvy about new technology and thinking about how to apply this to their work. In other words this is going to happen.

MS (to RK): I have one final question for you Rem, with regards to the role of architecture in this process. In emerging countries, more often then ever, buildings and institutions are built and closed again. In China, for example hundreds of museums are currently under construction but some of them are closed before completion. So architecture is sometimes an enormous aspiration. Architects are invited from other countries to build buildings, but oftentimes, ideas on how to operate these buildings, how to run them, how to collect art, how to build up knowledge and how to invite artists come up too late. I feel a strong imbalance between architecture and culture here.

RK: I think this really is a key issue, and enables me to answer some of the earlier questions, particularly on how architecture is evolving or can respond not just to new technologies but also to new interpretations. Architecture has been trained to develop, on demand, a response to almost any type of question no matter how outlandish or how premature, or however imprecise or incorrect. This alerted me early on to the absolute necessity to have an independent and often critical judgment vis-à-vis the current demand. That expresses itself sometimes in disobedience, which is sometimes successful, vis-à-vis clients or the organizers of a competition, or simply a profound engagement with the client in terms of proposing things. But that has also enabled or forced us to create a second part of the office, where the architectural office, the office that does architectural work, is called OMA, and the opposite mirror image, AMO, is the office that allows us to take a distance. It is not committed to building but to thinking about the appropriateness of an effort or to do research around a building effort, as well to research into situations where we may potentially be involved in. This would enable us to have a degree of independence.

We talk of a real cultural revolution in Singapore, I would like to get your take on this idea of a cultural revolution here.

MS: You know, there are revolutions from the bottom and the top, and maybe in Singapore you can observe both. On the one hand the authority and the state is pouring in a lot of money into the art world. It started quite some time ago. What I learnt is that there was a master plan called the Renaissance City in 1989 where the plan for a National Gallery had already been laid out, so it took some time to implement. I do believe that large institutions need time to develop in the fabric of a city. There is certainly a lot of state money available, more than there is in almost anywhere else in the region and that makes Singapore attractive in many ways. On the other hand, Singapore is a very expensive city, and many artists find it impossible to reside in Singapore as long as they aren’t very commercially successful. This seems to be a problem we face in other emerging cities.

I was living in Berlin for many years and one of the reasons it was so attractive is that it is cheap. In Dubai it was a similar situation, although it was not as cheap. Dubai seemed like the heterotopic space of the pan-Arabic society. In Dubai you could do many things that you couldn’t do anywhere else as an artist, whether in Iran (an Arab neighbour) or even less so in other Arabic countries. There was also a relatively high level of freedom of expression, so it made this place attractive and kind of a hub for the whole region.

This is of course a question for cities like Singapore too. Singapore represents a city population that is reflective of the region and also a platform for what is happening in nearby countries. If you go down to look at the galleries, the artists on display come from these countries. So I could imagine that this could become, over time, a role for Singapore as well.