Dear Por Por,

How have you been? This is Tsz Ying, your granddaugther! Sorry I''ve not kept in touch with you for so long. I 'm back in Hong Kong now, and am currently staying in a rented flat in Sham Shui Po district. Ma has been nagging at me for not keeping in touch with you enough, and said that you keep asking how and where am I! So when I walked around Sham Shui Po today I thought of you. Remember when you took me to eat from so many stalls? The siumai yudan with curry sauce, handmade bao dim of meat and chive buns, the dessert stalls and yun tun noodle shops they are all still there!

This place looks the same with endless stalls lining the streets selling anything from electronics to pot covers; sharing the narrow, busy roads with trucks, cars and styrofoam boxes after the stalls have unpacked their vegetables! Did you know that the Sham Shui Po police station is still here too after so long?

But things also seem different, like the high-rise residential and commercial construction projects taking place surrounding the older low-rise buildings. I see more ethnic minorities, largely South Asians selling wares or collecting used electronics (and speak much better Cantonese than me!).I hear more people speaking in mainland-Chinese Mandarin, and more homeless and elderly folks collecting cardboards and styrofoam boxes and selling whatever wares they can find on pavements.

I obviously got carried away with my memories of Sham Shui Po! How are you doing at Lantau Island? Have things there changed too?

Love, Tsz Ying

Rediscovery relies on a sense of recognising the old and familiar, which simultaneously awakens to something new and unfamiliar, which could prove exciting and/or threatening. In other words, it is in a terrain of relative familiarity that rediscovery happens. This notion of rediscovery is not merely ephemeral or a theoretical, abstract concept, but intertwined with embodied realities. For those who live within these realities, rediscovery reflects different trajectories and implications of possible futures observed in Sham Shui Po, Kowloon, Lantau Island as well as Hong Kong Island, despite belonging to the same Hong Kong.

As one of Hong Kong’s poorest district, Sham Shui Po has in recent years been labelled a tourist attraction accompanied by walking tours. It is marketed as a quaint district containing rich cultural heritage one could experience—from shopping at roadside stalls, dining at famous eateries, and visiting temples. Interestingly, the (literally) old and dilapidated surroundings are touted as 'heritage', and seen as a district where time seems to have frozen, leaving these scenes of history preserved. Rediscovery, as in Tsz Ying’s account of Sham Shui Po, is perhaps understood and experienced through feelings of nostalgia. It is both a form of historical emotion and memory, yet concurrently reliant on modernisation and progress, bringing about a sense of time that moves forward in a linear fashion—irreversible and unrepeatable. However, this fantastical notion does not hold: what if time has not stood still, but the rest of Hong Kong has moved forward in its pursuit of progress, while Sham Shui Po has been neglected and left behind? Such objects and spaces of nostalgia are then situated in both the past and the present, with the 'past' old of Sham Shui Po entwined with conditions of gross neglect and the derelicts of both buildings and working-class people, possibly glossed over under the auspices of a romanticised 'old' that comes with heritage' and 'nostalgia'.

The terms 'heritage' and 'nostalgia also carry assumptions of origin, accompanied by official narratives of traditions and histories with a sense of what is truth and fact. This ensures longevity of traditions and histories, while at the same time, implies a process of inclusion and exclusion. The presence of long-standing communities of South Asians and foreign domestic helpers congregating outside swanky shopping malls in Hong Kong have received much visible ire and irritation from the wider local public. Sham Shui Po is marked by the constant presence of police patrolling streets, standing at street corners, or police vans parked in the vicinity; public pavements are often 'cleaned' and doused with water to discourage elderly folk from displaying and selling their wares, and the homeless from sleeping on the streets. As these combinations of non-Chinese immigrants, the homeless and working class often bring about an ill-repute, it seems almost impossible for them to fit into Hong Kong’s (largely Chinese) traditions, histories, and spaces.

My dearest Tsz Ying,

It's nice that while the present Sham Shui Po reminds you of our shared memories, my Lantau Island holds Hong Kong's future! Do you know that the government has this new 'Lantau Tomorrow Vision' to reclaim more land in Lantau for public housing? Big changes coming our way!

But this project will take so long to finish. Can you imagine waiting least 13 years before a flat is built? Sounds so far away...I don't even know if I will still be alive then! My fishermen friends are also very upset more land appearing means seas will disappear. Where would they catch their fish to sell? How to survive in the future? A super typhoon also hit us last year... with the land facing so much change, can it still protect us from another typhoon?

This project sounds nice in promising a better future for us. But I don't know if it will really happen or be better. A lot of us don't trust the government since they don't listen to us or our concerns. We feel quite sad thinking we may not belong to that future... So sad, Tsz Ying.

Love, Por Por

Hong Kong’s reputation as a successful business and financial hub comes with vignettes of nostalgic, historical sites. Accompanying such mediated images are the underbellies of society relegated to the margins. While ironically lacking visual presence, some may have had their more than fair share of contributing to Hong Kong, either through informal market spaces that manage and turn our excesses of everyday wares and electronic products to second-hand goods, or an endless upkeep of domestic spaces. Perhaps as we walk around our urbanscapes, be it as locals, long-term inhabitants or tourists, we ought to conscientiously ask what guides our imagination of a successful city, and to what extent race and class differences shape belonging and (in)visibility.

Contestations of origin, histories and geographies are also expressed on a national perspective in the 'Lantau Tomorrow Vision' project, which aims to reclaim 1700 hectares of land in Lantau Island. Many Hongkongers took to the streets protesting this vision because of the exorbitant price tag (which comes from the public’s money). For them, this money could be put to better use, such as upgrading and repairing existing old buildings to make them safer and more elderly-friendly, as well as developing the existing 723 hectares of brownfield sites in the New Territories. Reclamation of Lantau also poses a real crisis to existing communities. Indeed, as Por Por opines, would she live to see the flats? Where would her friends catch their fish? Would they be able to survive another natural calamity?

At first glance, the project is about the literal reclamation of land, while on another hand it is about the reclamation of 'Hong Kong identity' tied to land. The term, 'reclaim' was used in an earlier terse incident in the area of Sheung Shui in 2012. Sheung Shui’s proximity to Shenzhen has led to soaring numbers of mainland Chinese tourists buying residential property in recent years. Sheung Shui’s profile of shops has also changed—where stores once sold everyday groceries and products, they now largely consist of pharmacies selling baby milk powder and health and skincare products, which attracts even more tourists. In a similar vein, the 'Lantau Tomorrow Vision' has been met with much suspicion because this reclamation project for the future is seen to ultimately benefit land developers (suspected to be companies from China), as this project is seen as a 'gift' to private businesses, backed by pro-government and powerful property developers. It is also perceived as expenditure aimed at connecting Hong Kong even closer to mainland China; touted as another gateway to the Greater Bay area, which is an ongoing project fervently campaigned to integrate Hong Kong with cities in Southern China.

Dear Por Por,

You know, some say the future is written in the stars, but I think Hong Kong's future is written on land and spaces not only in Lantau's yet-to-be-created land, but in urban spaces too.

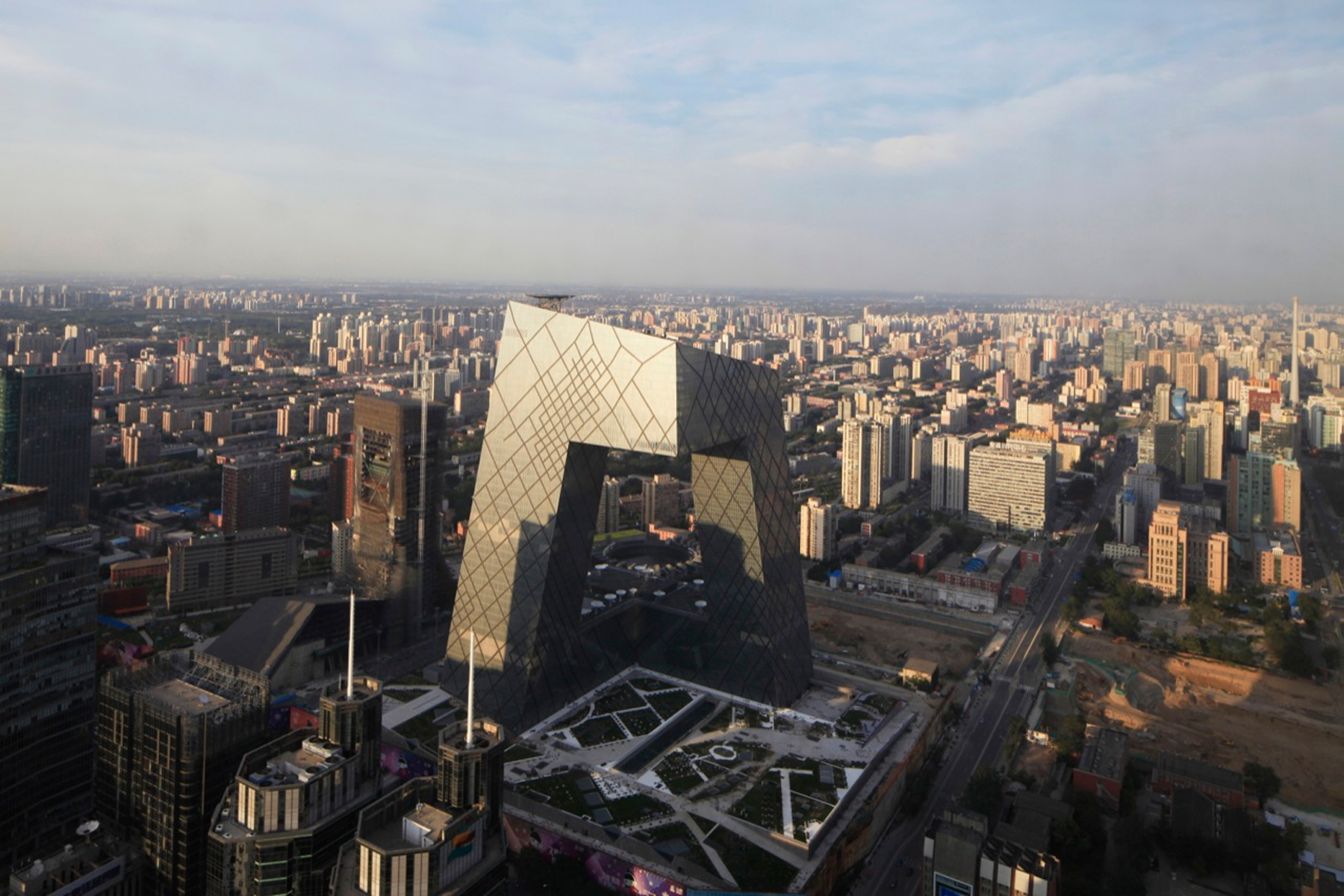

When working at Hong Kong Island, I feel like I 'm in another space and time! Roads are wider and cleaner, buildings are taller, shinier and look stronger; there are so many banks and shopping centres here with their big brandnames on buildings. These spaces smell so modern and I see many more escalators and elevators! I also hear more English spoken here than in Sham Shui Po. Even people's homes look so grand, like palaces.

It seems so impossible to stay on this Island and call it home. My friends tell me it is so expensive to stay here on the Island... domestic helpers have been in Hong Kong for so long, and I still see them having to sit outside these buildings when spending time eating, taking and sharing photos with their own friends...

Your fishermen friends are worried for their future... I think about the future too, and wonder who imagines and shapes our possible futures? Who decides if you and I and our friends can belong?

Por Por, do you think we have a place to belong to in Hong Kong's future?

Was this a future you imagined and hoped for in your past?

Love, Tsz Ying

Ackbar Abbas, a cultural critic, wrote of Hong Kong’s cultural identity as one that is caught in-between a “not quite there” (ie. Chinese but not quite there) and the “more-than-there” (ie. more than too open to other influences). Under the British colonial rule, a decolonisation policy was initiated in an attempt to distance Hong Kong Chinese from the then-China’s communist regime, as well as allow for a fostering of 'local' cultural identity. Post-1997 meant that due to its own development of history, a unique Hong Kong identity of 'Chinese-ness' was returned to China, and inevitably not quite Chinese in comparison to China’s. Grating differences were felt by Hongkongers, mainly regarding the switch from vernacular Cantonese to the Hong Kong government’s active promotion of Mandarin as the official spoken and teaching language. Such change was perceived as hegemonic, and led to a call for defence of Hong Kong’s cultural identity. With Hong Kong’s land currently being encroached upon and claimed by the Chinese government, it adds to existing deep suspicion towards the government.

Having close to a 98% majority of ethnic Chinese in Hong Kong’s population, it is ironic that against China’s goal to decrease physical proximity between these two places, it is the 'common' ethnicity that drives a much wider separation between them.

Ethnic differences do not solely explain Hong Kong’s tensions and exclusions, as local Hongkongers are not exempt from the exorbitance and difficulty of living in Hong Kong Island, a space dedicated as the financial hub of Hong Kong, and the haven of (very) well-to-do expatriates and business tycoons. Tsz Ying’s letter reflects how an imagined future (or lack of) is also written on land and spaces in Hong Kong. In the spatial differences between Sham Shui Po and Hong Kong Island then, while the former is fixed in its place as a nostalgic heritage district, Hong Kong Island is imagined as the bright future trajectory of Hong Kong, marching headlong towards modern aspirations of progress.

Such tensions and exclusions reflect how social processes and relations undergird these interactions and imaginations of the past and future. In stating how human life is spatial, temporal and social, simultaneously and interactively real and imagined, Edward Soja highlights how such social processes materially shape spatial and social relations of all kinds, including interpersonal relations and race-, class-stratifications. This can be seen in the vastly different materialities that exist in both Hong Kong Island and Sham Shui Po, from buildings and public infrastructure (or lack thereof), to the kinds of communities that live and move there.

Going further to link space with justice, Soja states how space, like justice, are both socially produced, experienced and contested on changing social, political, economic and geographical terrains. Unjust geographies are created through discriminatory decision making by individuals, firms and institutions, and geographically uneven development is a general process underlying the formation of spatial injustice. In thinking alongside Tsz Ying and Por Por’s concerns and anxieties regarding the past, present and future, in the context of larger, ongoing spatial imaginaries and tensions in Hong Kong, one also sees how geographies become unjust, arising from distributional inequalities.

It may be wise for us to seriously consider Soja’s words—while geographies that we produce would always contain spatial injustice and distributional inequalities, some of these have more dire consequences and deeply oppressive and exploitative effects, especially when sustained over a long time and rooted in persistent divisions in society, in our case, through both class and ethnicities.