To preface a discussion on Pop Art while paying homage to all the cults mentioned in this issue, we open this article with a declaration of intent. Since its inception, much of the conversation on Pop Art has centered on its artistic validity, questioning its status as art and pulling apart folds of irony and parody to determine meaning. While these are certainly important preoccupations, more pertinent to the layman is the impact of Pop Art on the social and emotional experience of the 1960s. To this end, this article strives to deliver an anthropological rather than aesthetic perspective on Pop Art. Instead of professing wisdom on either the merit or meaning of Pop Art, we offer humble observations on the mania of the movement. We turn our lens away from the art and towards the mesmerised faces gazing at cans upon cans of Campbell's soup with equal parts inspiration, confusion and apathy.

PARADOX OF POP ART

A cult is understood to push forth socially deviant ideas or behaviour. In its time, Pop Art certainly achieved this, aggravating artistic sensibilities by transplanting imagery from popular culture into the world of fine art. When Roy Lichtenstein's replication of DC comics exhibited to large crowds in the Upper East Side, the hierarchy which distinguished high art from low, a Rothko from a copy of the Superman Returns, was violently subverted.

Pop Art ruptured the melancholic and philosophical mood of post-war abstract expressionism by reintroducing identifiable imagery. Beginning in the '60s with Andy Warhol, then petering off in the '80s with Keith Haring, the movement expressed a thorough disinterest in the wailing existentialism of the elite, striving instead to reflect the concerns of the labouring masses, of the exhausted, the uncouth, and the materialistic.

In The Arts and the Mass Media, a seminal work outlining Pop Art, English art critic Lawrence Alloway argued that by the year 1958, advancements in mass media meant that artwork which failed to engage the reality of popular culture was likely to be anachronistic and irrelevant. Five years later, Time Magazine hailed the veritable arrival of ‘the cult of the commonplace’—a fitting title for a movement developed in direct opposition to the art establishment.

At its core, Pop Art may have been rebellion and mischief, but it also performed the honourable function of democratising art. Andy Warhol, indubitable Pied Piper of American Pop Art, famously decreed that "in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes." He further declared that "every painting should be the same size and the same color so that they're all interchangeable and nobody thinks they have a better or worse painting." With Warhol, it is never clear if he said these things in irony or conviction, though for the most part, it does not matter; he provided the language for reclaiming art and the crowds ran with it.

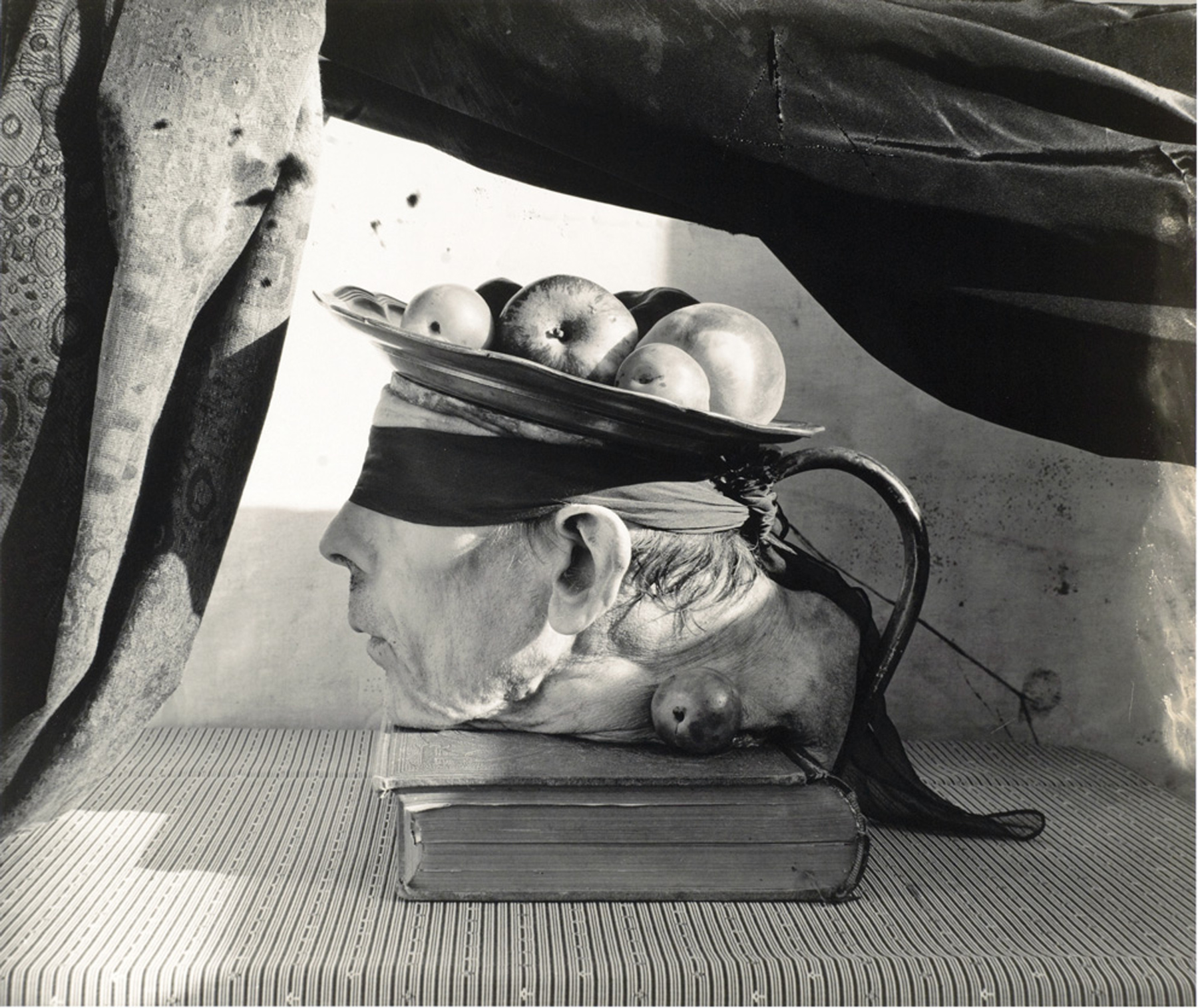

Many of the methods employed by Pop Artists closely resemble the mechanisms of a cult, and perhaps this was deliberate. To address a deep and sore sense of exclusion, Pop Artists overwhelmed cultural spaces in the same all-consuming way that a cult colonises the lives of its followers. Their emphasis on repetition and iconography is more than a little reminiscent of the obsessive memorabilia, the altars and little porcelain figurines that pervade the home of any dedicated cultist.

With their endless reproduction of recognisable images, Warhol and his ilk created art that engaged more people than ever. Yet, like the elusive hosts of the most grandiose party, the core engineers of Pop Art—particularly the man behind those Ray-Bans—were, and continue to be, frustratingly unfathomable. To the extent that Warhol strived to make his work as tangible and nondescript as possible, he strived equally to render himself almost entirely impenetrable.

Hence, while Pop Art manifested itself as a democratisation of subject matter, it was also, paradoxically enough, extremely exclusive. In 2014, Jed Pearl at the New York Review of Books discussed The Cult of Jeff Koons with a brief history into the ‘seductive tricksters’ of the art world. He wrote that when Marcel Duchamp produced his first ready-mades a hundred years ago, they were seen as ‘the ultimate insider's cool dude art joke.’ The same could certainly be said of Pop Art. To feel like you get it, to be able to pick out the movement's wry criticisms on commercialism and modernity, requires a sharp and well-honed sense of irony that often feels unattainable.

In other words, Pop Art is at once within our grasps and beyond our reach. We recognise but do not always understand, which is perhaps central to its enduring appeal.

WARHOLIAN WORSHIP

Phoebe Hoban, biographer of Jean-Michel Basquiat—neo-expressionist golden boy and Warhol's anointed muse of the '80s—described the elder Pop Artist as a ‘white-wigged Wizard of Oz’. This type of characterisation isn't unique. A quick glance at the literature shows that even the most staid academics finds it difficult to describe Warhol in anything less than a celestial light.

Moreover, these claims are not unsubstantiated. An art collective, The Independent Group, founded in the United Kingdom in 1952, is widely agreed to have been the original architects behind Pop Art. Members like John McHale and Alison and Peter Smithson were the first to seriously open the conversation on mass media versus fine art, but they did so with overtly political insinuations. Warhol was never as articulate with his intentions, and while he may have flirted with political satire, his real preoccupation was making Pop Art as trendy as possible.

As John McHale Jr. explained in a 2006 interview: "The difference between my father and Warhol is that McHale started Pop Art with a conscious sociopolitical left wing agenda to extend the boundaries of art whereas Warhol was almost totally apolitical, favouring a lifestyle of wealth and celebrity. McHale did not denigrate Warhol for this, but he recognised it was a difference in motivation, aspiration and artistic style."

Hence, while the Independent Group motioned for progress, Warhol worked instead to elicit and perpetuate worship. His presence dramatically changed, and indeed came to define Pop Art in the United States vis-à-vis the United Kingdom. In 1973, writer Alvin Toffler and artist John McHale observed of the artist: "He lives the work. It's his whole lifestyle which becomes the artwork."

Toffler added that Warhol redefined public engagement with art by cultivating interest not just in the finished product, but in the very nature of art production. "It is not only his discrete works which are interesting and important," wrote Toffler, "it is the cycle of works he produces, one after the other, it's the whole Warhol output." In appropriating the spaces and processes of mass manufacturing, Warhol created a new definition of the artist, one where "the product is linked, not physically, but conceptually, to the originator," said curator for art database Artsy, Matthew Israel.

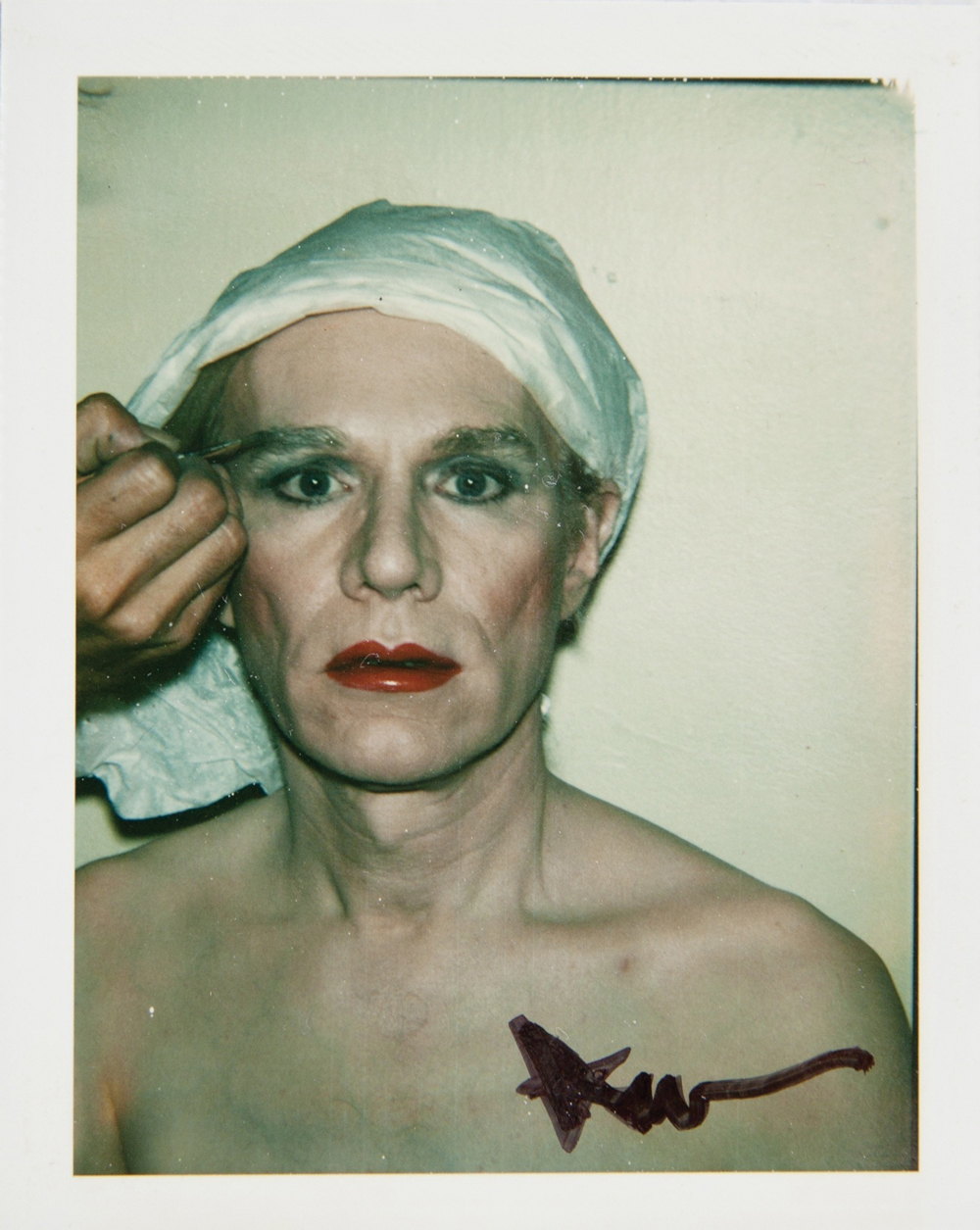

With deftness, acumen and, one must imagine, tantalising delight, Warhol engineered his own cult of personality. Not only did he distance himself from the conventional identity of artist as craftsman, he effectively elevated his namesake to the status of gross celebrity by flooding all mediums of culture with content of himself.

Warhol himself spoke several times on this idea of ‘aura.’ He expressed that his aura is not a product, but a result of his presence, and therefore "independent of his agency"; a kind of spiritual endowment, if you will. He actively maintained this blanket of mystery, speaking either in monosyllables or non-sequiturs. "I never like to give my background," he teased, "and anyway, I make it all up different every time I'm asked."

In retrospect, we can see that what Warhol and, to a lesser extent, all the other Pop Artists keenly understood was that casual disaffection has an incredible allure. When they answered questions with nothing but a coquettish half-smile; when they addressed traditionally revered themes of art such as sex, violence and patriotism with exaggerated boredom and superficiality, they took on a coolness that was infuriatingly seductive.

Warholian worship is as absurd as it is real. In 1982, Danish filmmaker Jørgen Leth directed 66 Scenes to represent America, inviting icons to perform an action of their choice on screen. Warhol chose to eat a Burger King Whopper and did so in four minutes. Leth remarked that the scene was ‘simply agonizing’ to shoot, which was precisely why he loved it. Andy Warhol eats a burger in silence, and because of his celebrity people are compelled to watch... and watch.

More recently, in 2014, Californian artist Jeffrey Vallance organised a séance with Warhol. Over 300 people gathered at the Underground Museum in Los Angeles to watch a psychic medium contact and consequently take on the spirit of the American artist who passed away in 1987. Putting aside the reception or even authenticity of the performance, a pertinent point can be drawn from the event's overall gesture: given the choice of an entire history's worth of deceased artists, Vallance chose Warhol to bring back to life.

This is perhaps the typification of what Warhol worked to achieve all his life: a status far beyond the common man, a legacy that doesn't fade passively into history but continues to incite mystery, allure and a cult following even his death. In his final and what must be slickest magic trick, the white-wigged Wizard of Oz orchestrated his own immortality.

.jpg)