Towards a

New Agriculture

by Tan Qian Rou

New Agriculture

by Tan Qian Rou

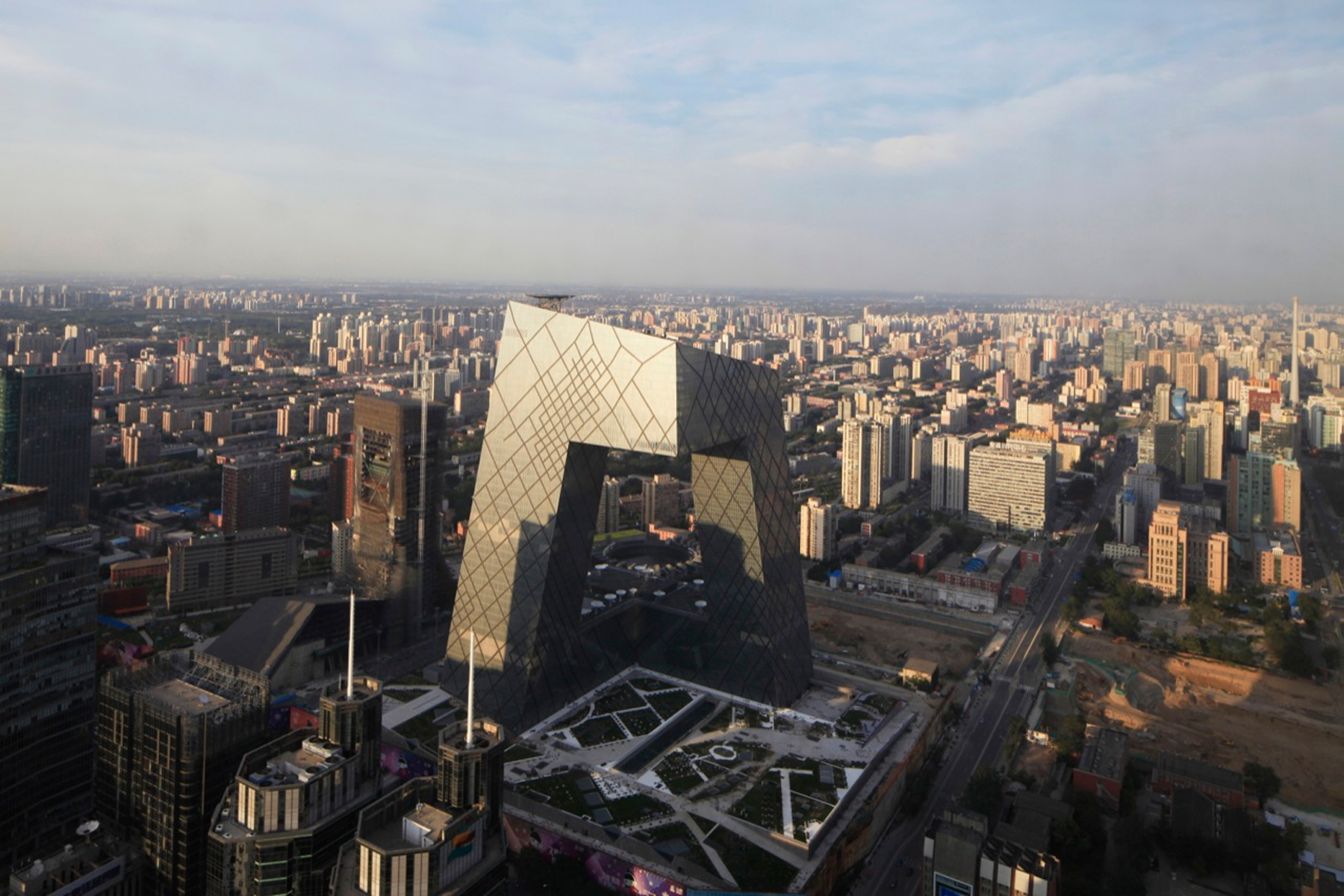

It was on the brink of the 19th century when we first saw it; first built it. A construction of altitude, the physical articulation of the power of man. They called it a skyscraper, for it soared beyond our vision, rising higher and higher with each iteration. It seemed to graze the edge of the sky, never quite touching it no matter how hard we tried.

Rem Koolhaas called it the ‘utopian device’, a generator for potential sites in dense and tired city centers. The implication was clear: if skyscrapers were the vertical limit, then everything below the peak was fair game. The obsession was understandable: having scattered ourselves across the map, the only way left was up.

This compulsive colonization, coupled with the onset of the industrialization of the 18th century has left us with a conundrum. A blind pursuit of capitalism lured the masses into city centers, away from their homesteads and farms, and we grew so packed that there was nowhere else to build but up.

Coupled with the subsequent stagnation of agrarian practices, the continued growth of cities was, and is essentially leading us into a projected food shortage. Skyscrapers may embody our technological accomplishments, but it is becoming increasingly apparent that they are also monuments to our folly.

It was energy and climate change that first made us aware of the need for sustainable practices in the late 20th century. Vehicular transport required too much gas. Building construction left staggering pollution and energy costs. And as skies turned grey and days grew hotter, a call to action became irrefutable.

Predictably and necessarily, architecture has latched onto sustainability. Zero-energy buildings, passive houses and artificial wetlands have become theoretical battlegrounds for the ecologically concerned. Inevitably, as sustainability establishes itself in mass consciousness, they have also become breeding grounds for mercenary projects. Too many buildings hide their staggering energy consumption beneath a green, gardened veneer.

The concern over edible produce has only figured into the sustainable debate in the last decade. While architect Ken Yeang spoke of incorporating agriculture into building spaces in the early 90s, it was Dr. Dickson Despomierre that gave the idea a form. He called his theoretical construct the vertical farm. It soared towards the sky.

It is not hard to visualize: rows of lettuce, tomatoes and other produced packed into land of a pre-determined size, stacked upon themselves endlessly. The idea is to pack our agriculture in the same fashion as we have done our people for over a century. The benefits, proponents argue, are twofold. The physical proximity of these farms to the urban populace would both eliminate the carbon footprint produce transportation generates, and serve as an education process. More importantly, Koolhaas’ s assertion still applies. Without wasting large patches of valuable land, we could, quite literally, pull farms out of the air.

Perhaps, part of the reason why many architectural offices are, as of yet, hesitant to commit to the idea of vertical farming is that the concept is highly problematic. The infrastructure required to irrigate 60 meters of farm, or even to provide them with earthly platforms is expensive and pollutive. These isolated green towers fail to integrate with the existing urban fabric of cities. The energy consumption of building and sustaining megastructures are impractical.

Most importantly, from a conceptual point of view, the supply generated from a single vertical farm would be nowhere enough to appease a fraction of our current demand. While the intent is understandable and perhaps even admirable, as long as we fixate on the idea of a ‘vertical farm’, which is at its core a skyscraper incorporating greenery, we submit ourselves to the hubris of man and architecture.

Another solution to the problem exists: urban farming. Often community-initiated and almost guerilla in nature, these farms spring up in small patches. They reject formalization, choosing instead to inhabit rooftops and empty lots. Their caretakers place the utmost importance on sustainable practice, transforming these plots into low energy consumers.

Unable to comprehend, architecture has, in the subsequent existential crisis, attempted to absorb the idea of urban farming into built space. This often ends up in tragedy, with the agriculture either flaunted as decoration or as an afterthought, stitched on to some building in spectacular, Frankenstein-esque fashion.

The true brilliance of urban farming is that it occurs in existing spaces. Architecture, ironically, often fails to realize that these existing spaces don’t necessarily have to be programmatic voids; farming and other functions can occur in the same physical space.

Located in downtown Tokyo, Pasona HQ by Kono Designs is an astounding example of architected urban farming. Vines creep suspended over conference tables, fruit trees take the place of folding screens and beans fatten quietly under various benches and chairs. The produce, often cared for and harvested by employees, is served in the office cafeteria. A dynamic green wall composed of seasonal flowers pulls double duty as both visual attraction and thermal barrier. Rather than a wistful nostalgia for natural living, Pasona HQ’s microfarm is a highly technological experiment in urban farming. Intelligent control systems establish a climate suitable for both agriculture and human living, creating an ecosystem between the produce and the employees.

Beyond immediate aesthetic and environmental benefits, Pasona HQ also plays a role in ecological education. Seminars and internships not just in the methodology but also management and financial aspects of urban farming are held on the grounds. In a country where farming is not viable due to scarce arable land, Kono Designs has provided a feasible solution which is not merely symptomatic but generative.

Across the Pacific, New York bears witness to a steady increase in urban farming. Rows of crops cover rooftops and deserted land, sustaining local restaurants and communities. This movement is born not of the same architectural capitalism which engenders our current built landscape, but a revolution in ecological thought affecting a collective social consciousness.

As long as technology burgeons, there will be no end to the sustainable issue. Generating congruent arable landscapes, particularly in an urban context, is entangled in a confusion of political, social and architectural agendas. Perhaps a step forward would be to detach ourselves from our instinct to build and create, instead, returning our built environment to nature, one rooftop at a time.