“The medium is the message,” Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964. He noted that when we use a tool that that stretches our capability, it also modifies, or amputates, some aspect of that ability. The question he posed was not what technology could do for us, but what it was doing to us.

Forty years on, is there anything different, then, about the contemporary self? Every artist and thinker since has been critical of the 'self' streamed through digital powers. Through much of these run a thread of unreality and impermanence. Sherry Turkel, for instance, has called virtual reality a “heady world (of people) performing themselves” online by constantly updating Facebook profiles and tweets to show an ideal version of ourselves. Wild.

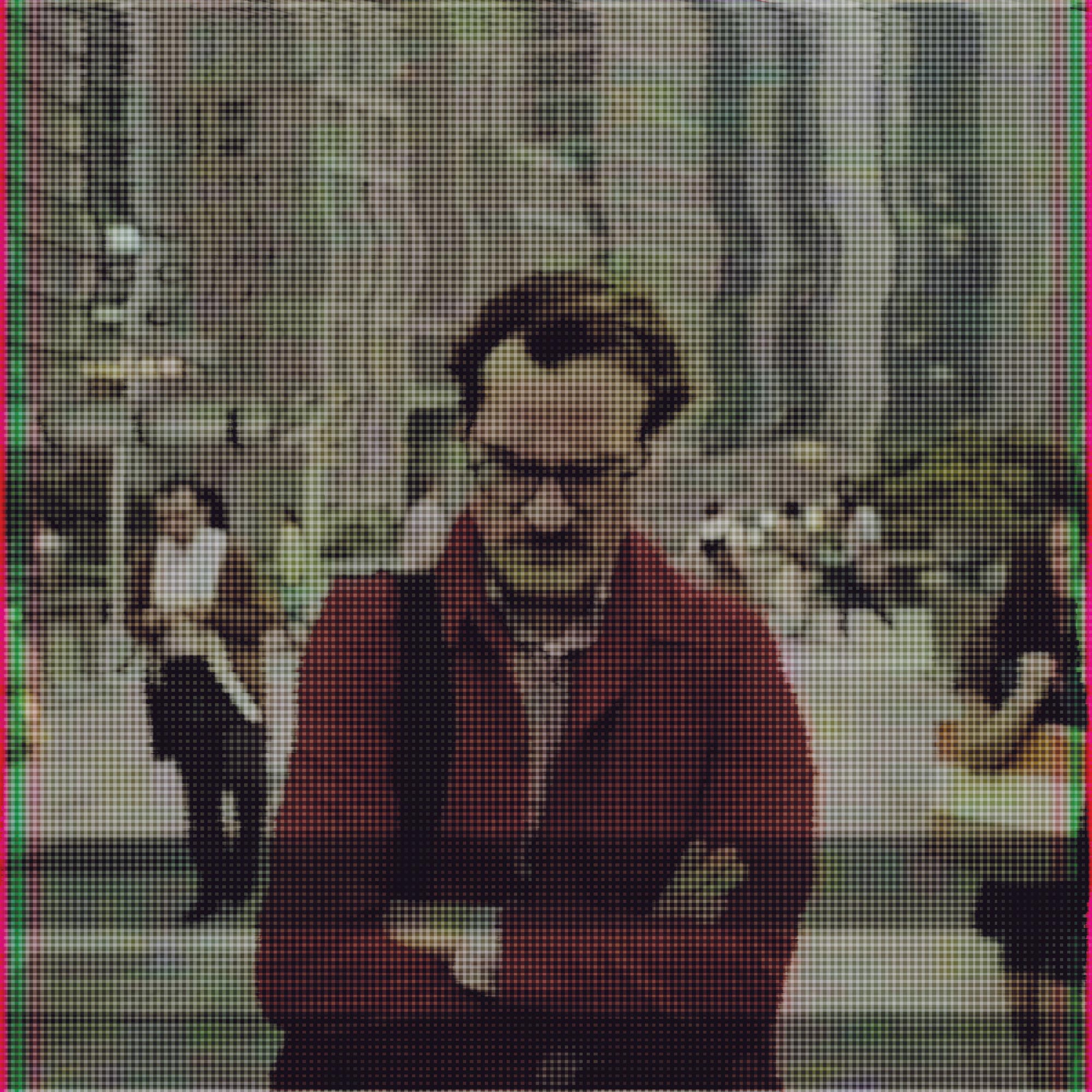

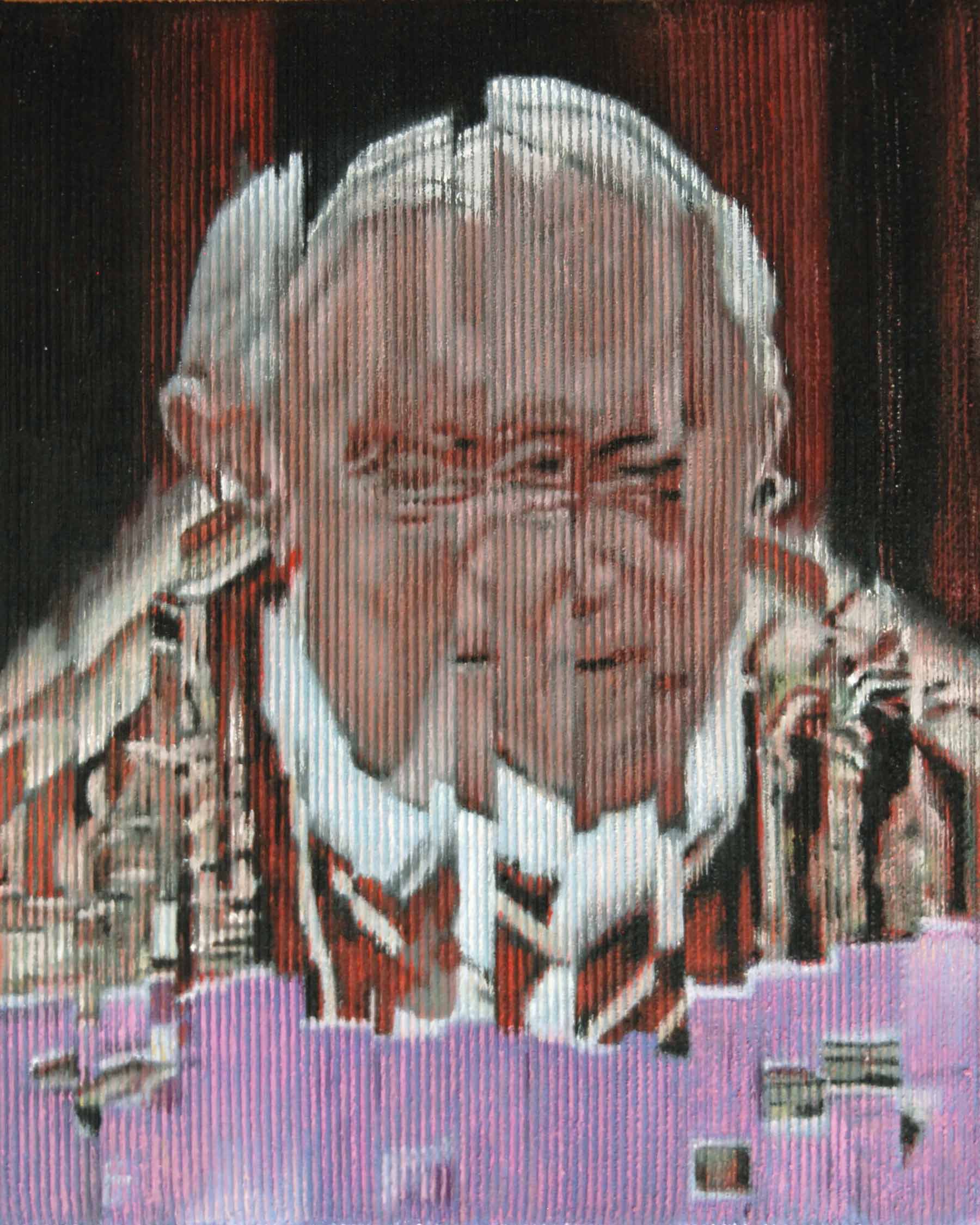

Jens Hesse examines this fundamental question by dropping the focus squarely on one—a person, a horse, vistas—or a couple, the first tenous connection with another. His paintings are a mixture of plaintive scenes, paint and glitches, a world saturated with media. He himself spent close to a decade designing denim in fashion, and his paintings reveal that irrevocable mish-mash of both art and technology. His technical skill is unquestionable, and his canvas, often denim by the way, positively seem to emote.

Looking at a Jens Hesse painting is like tuning into a home more technological, more global, more cyborgian than you ever thought it was. At once empathetic and alienating, Hesse’s poetic glitches hint at the humanity just beyond the technological mirage. But that hope hangs on the tightrope of perception. And you can’t help but think at the end of it, there is a price to pay in the individual lack of cohesion. We sit with the artist for a conversation fraught with these questions.

What fascinates you about interference? Is the process or the object of interference that catches your interest more?

Initially, it was the interference itself that caught my eye. I found beauty in these errors, this mix of abstraction and realism. But there was also a deeper meaning. How does the world work in today’s time, when everything is influenced by technology? What is real and what is not? What happens behind the screen, in this world full of clutter and noise?

At the same time, I was experimenting with paintings on different structures to give my works a new approach, and my first paintings on corduroy showed exactly the character of these television pictures—the vertical stripes that gives a fluttering effect, like the painting is still moving. So I combined my new technique and the visual impact of the interferences.

My first paintings were based on images that I took from interfered satellite-television. It was a realistic reproduction of our media-saturated world, but also revealing of its insufficiency, showing it is not real. Later on, the object itself became more important to me. I was engaged with provoking similar interferences on objects that I chose on my own.

You worked for a time in fashion—an industry known for its saturation with advertising, media, and production of images—working for brands such as Wrangler and Esprit, before you left in 2010 to paint fulltime. How was your time in that world was like?

The advertising and image production in the fashion world is driven more by marketing, while me as a designer was focused mainly on the product itself. We worked in a certain framework, for a certain theme and the same target group, but there was not actually that much communication between design and marketing.

Studying fashion design was a commercial alternative to studying art—to still do something creative. But the bottom line was it’s a huge industry where so many people, opinions and factors are involved that there was not that much space left anymore to make decisions on my own as a designer.

Working in the fashion world influenced my work as a painter mainly in technical aspects. Working not only on traditional canvas but also on other materials and structures like corduroy, Piqué or boucle, helped me today to get this digital look in my paintings.

So I stepped out for a while to focus on painting only, but in the meantime I freelance on denim-products to have a second income. It is quite enjoyable once you understand that you cannot express anything personal in this job, but just enjoy making good products that can attract a wider audience.

Most of your artwork is portraits. For example, Pope 2 (2010), and others such as Woman on TV screen (2010) feature the face full and frontal, while non-portraits of animals and in nature take a longer detached perspective, like your overview in Grassland (2010). Was this difference a deliberate one?

I do find a lot of interest in facial expressions as they become even more expressive because of the distortions, for example when elements are multiplied. But there is a very fine line between making them interesting or just ugly.

With landscapes, I like the emotional contrast of nature and the visual technical influence on it. It nearly hurts to realise that it’s not real.

How do you make a decision on what to

distort—or not?

It's just things that interest me. It can be a nice image or an interesting movement, such as a video scene, where I assume an interesting result after destroying it. It can be a facial expression or a gesture, or just a beautiful landscape. There can be a deeper meaning behind it, but it is also a personal motivation. Because I like it. I don’t really like justifying why I paint what I paint.

Your art seems to take technology in its stride. At the same time, you take very much a photorealist approach, which faces its fair share of criticism about its meaning, in particular that it is “illusory”. What do you say to this?

That’s indeed a very important message of my paintings, that technology is illusory. That’s why my interest is more in the shortcomings than in the perfection of it. To reveal it’s not real, it’s fake, it’s manipulative. Painting it gives even a further dimension of manipulation.

I am a fan of modern technologies. It entertains us and makes our life easier in many ways. But it also bears the risk of taking too much control over our life. The media often just let us know what they want us to know and they make us think what they want us to think. It’s easy to manipulate. I want to make people think about how we are influenced by the digital world. Our today’s world seems to be real and perfect, but it isn’t.

Who are some of your influencers?

Gerhard Richter’s wide range of subjects and techniques is inspiring. He said that he was not painting “images” but “images of images”. He transferred the character of a medium into his paintings, which was in his case the blur-effect of photography. Distorted satellite pictures, a more contemporary phenomenon, influence me and I translate the visual character of digital media into my paintings.

Richter also said that painting realistic and abstract is the same for him. I feel pretty much the same, that both is challenging in the same way to bring something interesting to life.

Finally, I’m just curious now. Why Antwerp, Belgium?

I came to Belgium for a fashion job in 2006, and there was no doubt about choosing Antwerp as my residence. I already knew it quite well as I always used to come here for the fashion-shows of the Royal Academy of Fine Art, which is popular worldwide. I also like the medieval and village life character, but at the same time, Antwerp offers all benefits of a big town. My wife and I just bought a house so we will still stay for some time.