“Wait... I’m sorry. You’re dating your computer?”

“She’s not just a computer, she’s her own person. She doesn’t just do whatever I say.”

“I didn’t say that. But it does make me very sad that you can’t handle real emotions, Theodore.”

“They are real emotions! How would you know...”

“What? Say it. Am I really that scary? Say it. How do I know what?”

***

At the heart of the lovers’ fight in Spike Jonze’s Her is the ambivalence of human relationships. What is at stake in the argument is not only the revelation of Theodore’s romance with the operating system Samantha. It is that his own relationship with Catherine was devoid of real emotions. In this conflict, the personhood of things and the thingliness of persons are confused. Most uncanny of all is love itself, which Amy called “kind of like a form of socially acceptable insanity.”

The narrative trope of a man who falls in love with an inanimate object is a familiar one: in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, we encounter Pygmalion, the sculptor who falls in love with his creation Galatea; in The Sandman, Nathanael is enamored of the automaton Olimpia. Does it matter if the object of our affections are, in fact, objects, if our emotions are real? On a more disconcerting note, how different are they from their 'human' counterparts? In Hoffmann’s unsettling tale, Sigismund counsels Nathanael about Olimpia’s impersonality, describing her glance as “so utterly without a ray of life—without the power of vision.” Sigismund sums it up: “She seems to act like a living being, and yet has some strange peculiarity of her own.” To which Nathanael passionately retorts:

“Olimpia may appear uncanny to you, cold, prosaic man. Only the poetical mind is sensitive to its like in others. To me alone was the love in her glances revealed, and it has pierced my mind and all my thought; only in the love of Olimpia do I discover my real self.”

Before we judge Nathanael for his wilful self-deceit, we should note that the suspiciously taciturn characteristic of Olimpia had been described as being a virtue in Nathanael’s fiancee, the human Klara:

“Misty dreamers had not a chance with her; since, though she did not talk—talking would have been altogether repugnant to her silent nature—her bright glance and her firm ironical smile would say to them: ‘Good friends, how can you imagine that I shall take your fleeting shadow images for real shapes imbued with life and motion?’”

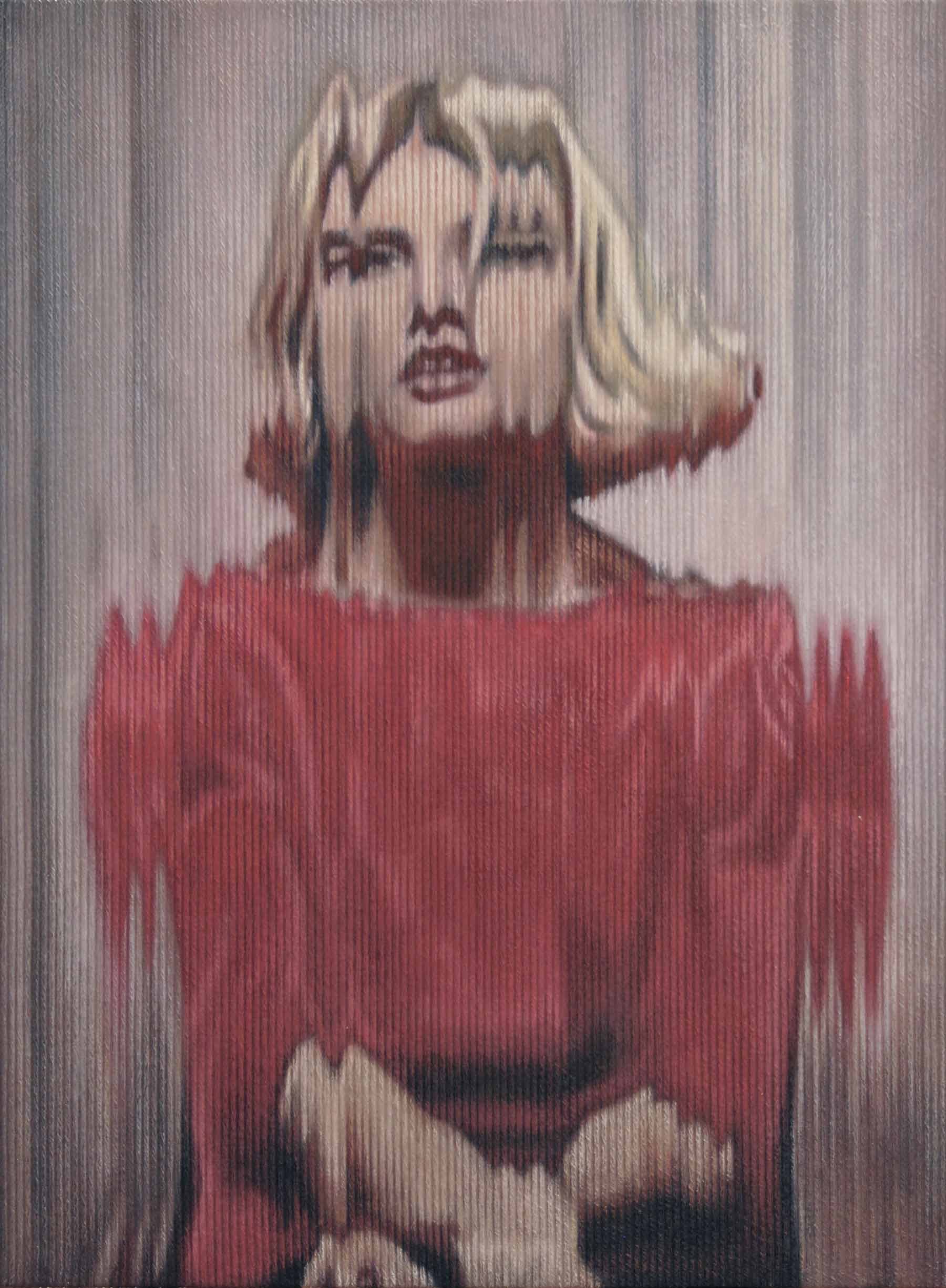

In Klara as in Olimpia, vacuous passivity is merely a dull reflection of the beholder. But the conviction that “only the poetical mind is sensitive to its like in others” may imply that the converse is true. Are we thus trapped in Plato’s cave doomed to idiosyncratic simulations of others, whether automata or human, and the world outside us? It is unsurprising that The Sandman is the focus of Freud’s seminal essay on the uncanny. What is uncanny is not only how human the doll seemed, but the disturbing recognition of how mechanical people are. The valley in which this lies is the troubling realisation that emotions and intelligences both real and artificial may be ascribed to human persons as much as they do to statues, dolls, automata and operating systems, and it is at least in part the delirium of love that redistributes our senses and plunges us into this valley.

In the epilogue of The Sandman, the narrator observes how the scandal of Olimpia had sown in people “a pernicious mistrust of human figures” with lovers requesting of their mistresses to sing a little out of time and dance a little out of step, and most of all to talk “in such a manner as presupposed actual thought and feeling.” The example of Olimpia may seem quaint but the underlying impulse to simulate humanity persists in our cultural imagination in the guise of ever-evolving technological avatars. In Her, the operating system Samantha is merely a projection into a future probably not too far away.

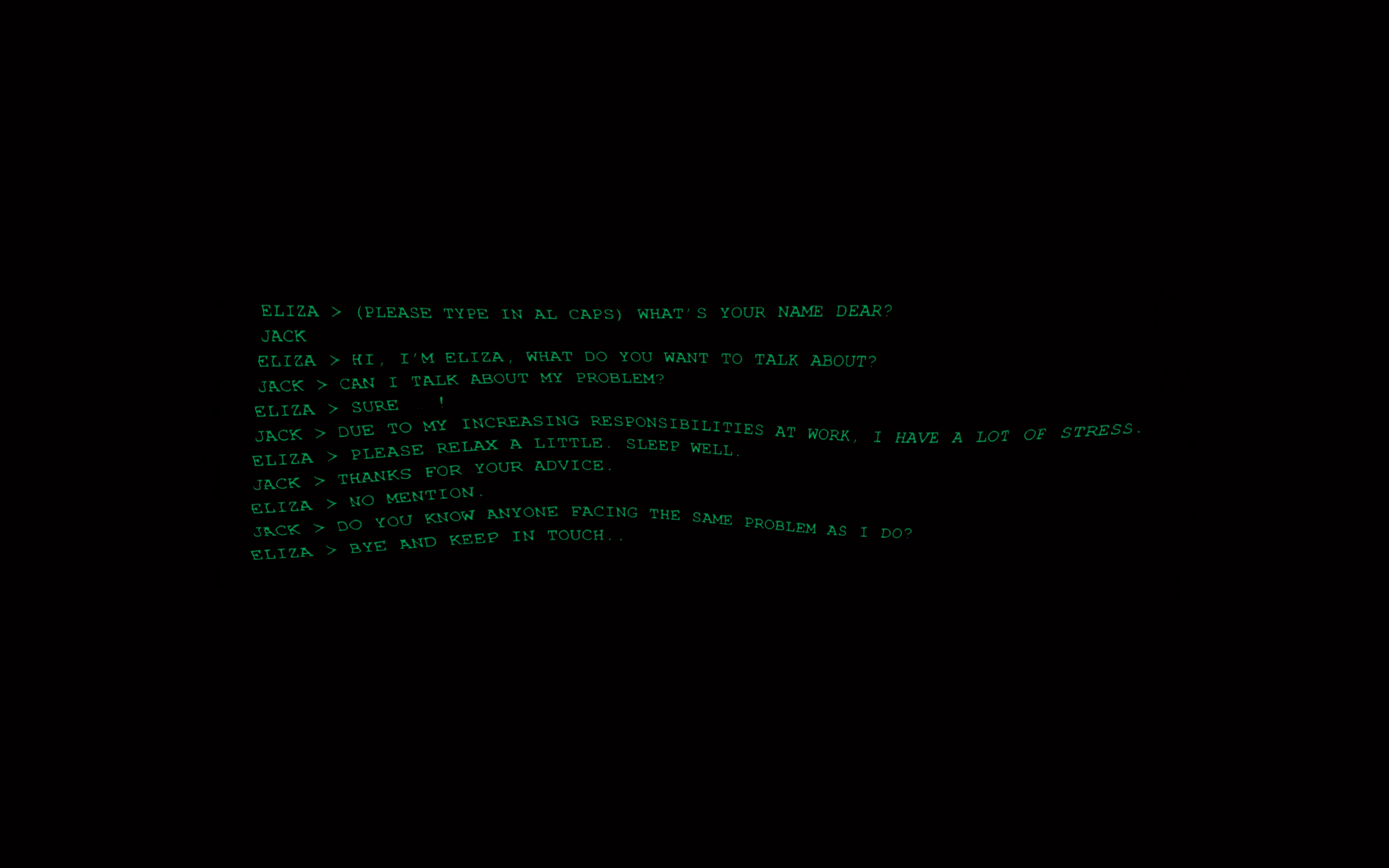

The episode Be Right Back in Charlie Brooker’s sci-fi dystopian series Black Mirror seizes on our contemporary obsessions with social media. When her boyfriend Ash is suddenly killed in a road accident, Martha seeks solace in a computer programme that amalgamates Ash’s available information on the internet to produce a coherent profile that could respond realistically to Martha’s messages. What begins as a text-based service that recalls early computer programmes like ELIZA, develops into phone calls that simulate Ash’s voice, and ultimately what appears to be a physical synthetic version of Ash himself. What slips through the algorithms of the simulated Ash are the paradoxes and capacity to surprise that characterise our human selves. The simulation also casts into sharp relief the distinctions between our ‘authentic’ selves from the often more flattering synthetic avatars we propagate online that are perhaps artificial but no less real. So what is it that we demand from these simulations? Will our technological surrogates ever suffice as objects of real love?

In Simulation and Its Discontents, Sherry Turkle explores the myriad ways in which simulation—and, I would add, love—“demands immersion and immersion makes it hard to doubt simulation.” In simulation, as in love, the partitions between the real and the artificial, the authentic and the synthetic, the person and the thing, diffuses as we become immersed in each of the experiences.

Skepticism is incompatible with the very project of love (and its simulations) or simulation (and its loves). It is only at the edge that we begin to experience the reality of our lovers beyond the mirror of our projections and simulations, so that a more authentic, a more uncanny form of love might emerge from this vertiginous valley of familiarity and strangeness. When we experience the frustrations and discontents of the other, when we catch ourselves surprised, when harmony is disrupted.

The solution is not to develop more sophisticated Turing tests to parry ourselves from the artificial and to buttress our realness. In his book You Are Not A Gadget, Jaron Lanier cautions us about the ambivalence of Turing tests: “You can't tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you've just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you've let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you?” This is a caution that bears uncanny resonance with advice in love and the extents we go to sustain these illusions with our cruel optimisms. I do not believe that our engagement with 'artificial' intelligences inevitably unmoors us from 'reality'.

Simulations need not only be proxies for the real—like the inhabitants in Plato’s cave, we can glimpse reality from the shadows it cast without taking the shadows as 'real'. The Turing tests do not assuage our technological anxieties or reassure us of our humanity, as much as it draws attention to the contested territory of who and what deserve the rights to be ascribed humanity. Alan Turing was himself no stranger to uncanny loves. Apart from breaking the code for the Enigma machine during World War II and becoming a key figure in fascism’s defeat, Turing was prosecuted for homosexuality in 1952 and subjected to chemical castration which eventually led to his suicide two years later. Before pleading guilty to the charges for gross indecency, Turing wrote to his friend Norman Routledge:

“I'm afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future.

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines do not think

Yours in distress,

Alan”

Even for someone who has demonstrated exceptionally real intelligence and emotions that are all too real, Turing, as Andrew Hodges writes, “must have known the same soul-destroying burden of being counted as less than human.” By now, we should become suspicious of the reality we are immersed in—we should recognise that it is a cultural reality, but not necessarily a privileged and self-assured epistemological stance that patronises the 'artificial'. Turing’s tragedy should alert us to the artificial trappings embedded in our cultural systems that we might unconsciously elide as the incontrovertible 'reality'.

It is perhaps only in the uncanny loves, in the glitch of the simulations, that we may begin to perceive what is real. It might even turn out that our loves are real.