“Life is a bitch. And then you die.”—Courtney Shayne (Jawbreaker, 1993)

Inspiring words to live by, uttered by a High School Queen Bee in the poorly rated predecessor to Mean Girls. Most would recall the atrocities of identity formation in high school. In a high-stakes game of popularity, covert codes of conduct sometimes become laws unto themselves; sartorial choices, for instance, and the clique you belong to. Thrown out in the ‘real world’, how then is identity expressed? Choice, once limited to whether or not one broke the rules, is now far more porous, and far more understated. And yet, perhaps we are always seeking the same things: identity, belonging, difference.

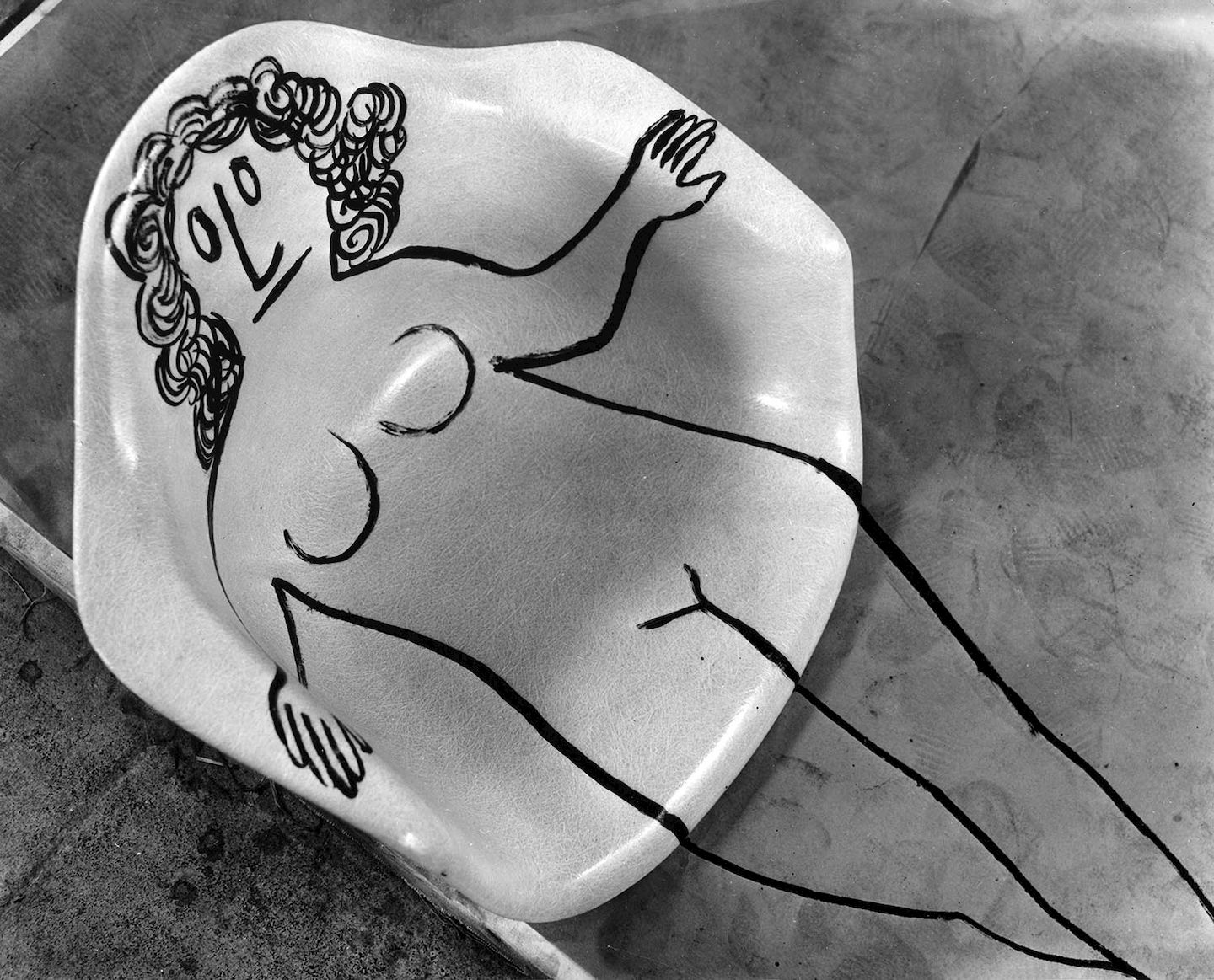

‘The world is your oyster’, we are often told. But before we can plunder the mollusc to our hearts' content, we must first grapple with the notion of self. With foetal notions of self-identity, one is naturally predisposed to differentiation, drawing lines in the sand to separate us from them. A select few will become heady with power, intoxicated with the ability to influence.

At their core, cliques are about the negotiation of identity amongst the student populace. The gaze of the collective peer group suddenly becomes devastatingly important; the misalignment of it with a personal one often the cause of undue levels of discomfort.

“On Wednesdays, we wear pink.”—Regina George (Mean Girls, 2003)

Sartorial means of social distinction in a scholastic context has almost become a rite of passage. The too-short skirts and tailored pants, the coloured hair, (‘no sir, it was the chlorine in the pool, I swear’,) the ankle socks that refuse to be seen above shoes; in schools where a strict uniform is expected, attempts at rebelling against the dictated dress code continue to be the mainstay. A parallel code, separate from the one determined by school management, will naturally come to form. In a top-down system which necessitates uniformity, it has become an imperative for some in the student populace to fashion themselves separate from that which lacks individuality. The irony is that others soon follow suit.

What happens then, should you find yourself on the outside, ignored or attacked for the mere virtue of difference? Waves of disdain from one individual spreading out over the populace like bacterial growth. Theft, threats, and on more than one occasion, death. The Laramie Project and the murder of Matthew Shepard may be the most painfully accessible example, but unfortunately he is not alone.

This insanity might have a scientific backing. Research by the Children’s Hospital in Boston concedes that the frontal lobe of teens—a part of the brain that ‘manages impulse control, judgment, insight, and emotional control’—is not fully developed.

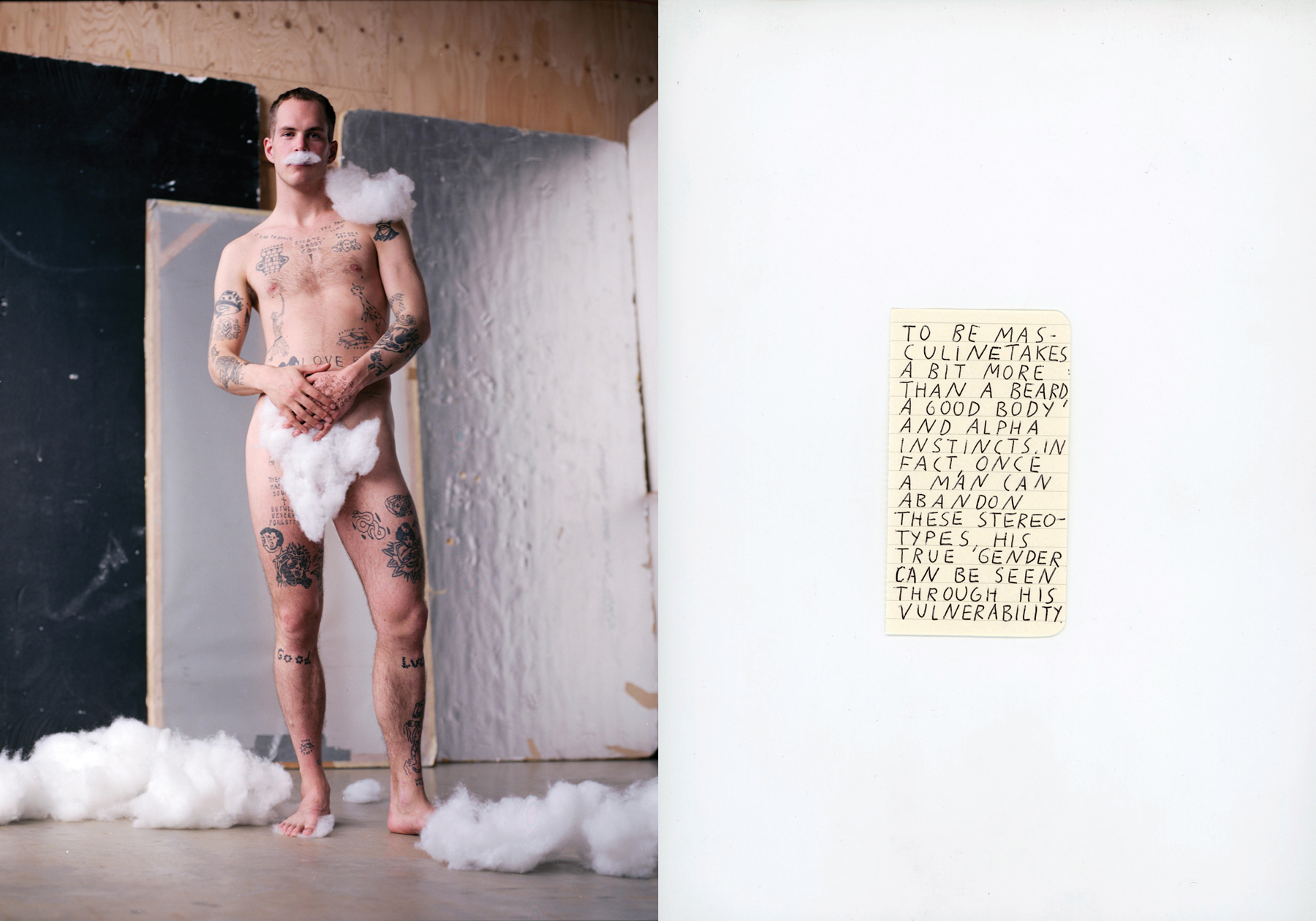

The uncovering of similarly ostracize peoples has thankfully engendered reclamation of the outcast identity, the embracing of which returns the power of identity to the accused, and in turn renders further differentiation by the self-proclaimed elite impotent. More often than not, these kids reference groups beyond their own community, beyond their borders, made easier in the age of the internet. The rebellious rock aesthetic á la James Dean. Arts students referencing the minimalistic bowl-cuts and bobs of female Japanese artists. Temporal and spatial restrictions no longer have any hold over the identities we choose to express. By adopting a facsimile of their behavior, we can generate an imitation of belonging to a group that need not be aware of our existence. Extraordinarily convenient.

Eventually, it may be argued that the clique is a necessity in an enclosed institution. What happens then, when we traverse out into the wild unknown, the ‘real world’?

Garment choices, for one, now far exceed what we were allowed. Now, more than ever, our choices are markers of who we want to be seen as, who we want to be, and perhaps, roles we begin to play. Dress codes of certain professions offer far less room for rebellion, with far worse consequences.

After the enforced uniformity of the school, is it not quaint for people to veer towards the adult version of the student handbook, following what others deem to be the ‘appropriate’ wear for the seasons and styles? In the age of Instagram, the word ‘trendsetters’ has been used enough to render the term almost obsolete; still, people look towards perfectly filtered Instagram feeds to determine purchase.

Perhaps the adult version of the clique is that policed by wealth and resources—and more importantly, the outsider’s view of it. The relationship of the nouveau riche—especially the emerging class of Chinese merchants—and luxury brands have been elaborated incessantly (through the use of brand names to signify status, for instance). A glace askance to another’s titanium plated Richard Mille, a twist of the arm, the flash of a label. Never have a group of individuals taken the Shakespearean adage so seriously—all the world’s a stage indeed.

For a select group, however, one’s garment choices will be inexplicably tied to identity, and to a large extent, the notion of belonging. The peacocking of crowds outside the industry fashion week, with their neon-specked platforms and fur-tailed headpieces may be lambasted by the old guard of attendees. Yet, the euphoria of dressing up and the veritable carnival of colours and excitement outside a designer’s showcase can almost be considered tribe-like, attracting attendees who wish to be part of the crowd and the show. Narcissistic potential aside, the physical garment as a means of creativity with the self as a medium is perhaps most poignantly portrayed at such an event—underscored by the celebration of another creative’s work whose garments are not his own.

Belonging, identity, sense of self: all-too human attempts at making sense of our existence, one that is paradoxically paralleled to others’. School, with its petty politics over seemingly insincere issues may have engineered a semblance of such an identity. But what of the world outside? The world is far larger, as I’ve found, but so too are the range of tribes to which one can choose to belong to. What, after all, is human identity other than a human construct, and thus subject to all the whims and follies and choices of us, its makers?