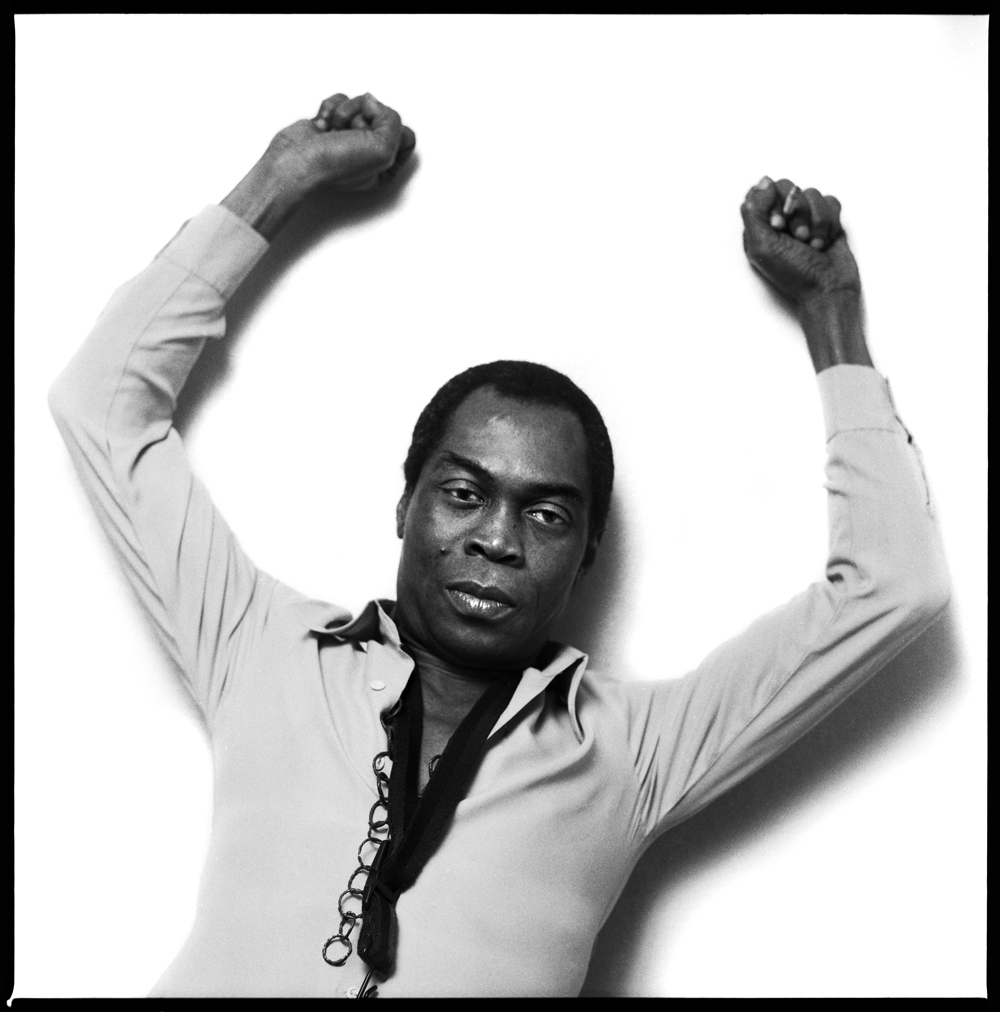

Fela Kuti is one of Nigeria’s most controversial and inspirational cultural figures. With his band, Africa’70, Fela was a musical leader in the blend of Yoruba music, jazz, West African highlife, and funk. They recorded nearly 50 albums over two decades, creating new music rhythms, incredible grooves, and arrangements popular across the US, Latin America, and Europe, and remain so among Afrobeat afficionados today. Their polemical lyrics criticised the political condition in Nigeria and in other African countries.

In one of their few pro-shot concerts, playing for the jazz festival in Berlin, 1978, Fela called out:

“You are going to sing with us. You are going to sing. It is a game, a spiritual game. But because it is not accepted, we call it the underground spiritual game.”

HIGHLIFE TIME (1968)

Born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti on 15 October 1938, in Abeokuta, Nigeria, Fela was the third of four children. His parents held conservative values and strong patronages in anti-colonial politics. His father, Israel Oludotun Ransome Kuti, was an Anglican priest and a talented pianist. He had waited 12 years to marry his mother, Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, who was a teacher and a women’s rights activist. With her flair for politics, “Mama Fela” led the Abeokuta Ladies Club in 1948 in a successful crusade against exploitative tax policies.

At nineteen, Fela left for London due for a career in medicine. He dropped out and enrolled instead in classical music at Trinity College. In 1960, tired of the European education, he left to form Koola Lobitos, which became a top jazz band in London.

Fela’s early influences were the James Brown-style singing of Geraldo Pino from Sierra Leone. His varied interests also fuelled his talents. He was a singer, songwriter, and composer, who was fluent in the trumpet—his preferred instrument, keyboard, and saxophone. His voice was a heavy, melodious, rich tune, which he used to speak truth to power.

GENTLEMAN (1973)

I am not a gentleman like that.

I be Africa man original.

A music tour in 1969/1970 was a radical turning point introducing Fela to the writings of Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, Marcus Garvey, the Black Panthers, and other proponents of Black Nationalism and Afrocentrism. Koola Lobitos was rebranded to Nigeria 70.

Back in Nigeria, as his London-style of jazz failed to take in Lagos, he would heed his mother’s words to sing what people would really understand. He named his recording studio “Kalakuta Republic” (with himself as president declaring its independence from the state ruled by the military junta), and his nightclub, the Shrine. Dropping what he called his hybrid slave name “Ransome,” he took the African name “Anikulapo,” or “he who carries death in his pouch or pocket.” He said, “I will be the master of my own destiny and will decide when it is time for death to take me.” His mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, would do the same.

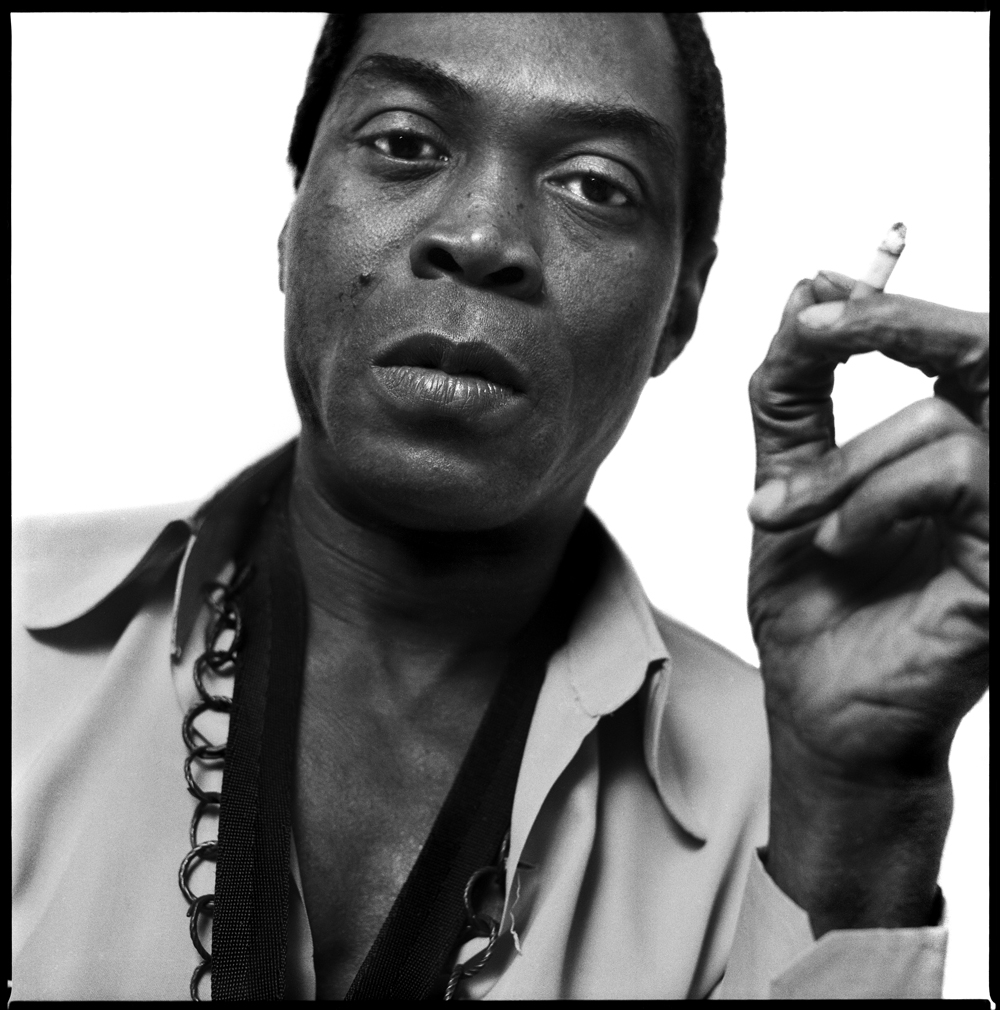

Fela took up the saxophone himself in this album after Igo Chico left the band. He sought provoking ideologies of Africa, using the pidgin language of the people: “As far as Africa is concerned, music cannot be for enjoyment. Music has to be for revolution.” As his audience in Nigeria and across Africa grew, every single they released was a danger that the group would be thrown into jail.

ZOMBIE (1977)

Attention! Slow march! Quick march! Fall in! Fall out! Go and kill! Go and die! Go and quench!

No brains, no job, no sense joro jara jo; tell am to go kill joro jara jo; tell am to go quench joro jara jo.

His album “Zombie” was a runaway hit with its upbeat and deeply funky rhythms. Its titular twelve-minute long song was a big fat middle finger to the military dictatorship in Nigeria. Seen as an antagonistic rally against the spineless un-intellectual ranks, “Zombie” carried a taunting intonement by a backing chorus of women. His website describes it as the “most inflammatory album Fela had released to date (which is saying something), ‘Zombie’ triggered the power structure’s most vicious reprisal.”

By this time, Fela was already in the crosshairs for relentlessly exposing army and police violence. The tabloids lapped up his “pungent quotes,” according to one paper. The New York Times called him “an epitome of indiscipline.” But was his fame fanning the flames of his activism or the other way around?

The song sparked the final ire of the government. On 1977, a thousand-strong soldier army stormed Kalakuta, destroying his tapes and the studio. 75-year-old Funmilayo was thrown from a window, leading to her death a few months later. Half of his staff members were killed and Fela was exiled from the country.

"The human spirit is stronger than any government or institution."Fela Kuti

Just two years later, however, Fela’s performance of this song was alleged to have sparked the street protest in Ghana, which was against the then military regime. Fela formed his own political party, Movement of the People (MOP), which quickly dissolved as he was barred from politics. In October 2020, amidst protests against restrictions in the Covid-19 restrictions, his youngest son Seun Kuti announced the revival of his father’s political party.

INTERNATIONAL THIEF THIEF (1980)

Then he gradually, gradually, gradually, gradually

Them go be, friend friend to journalist

Friend friend to Commissioner

Sentenced to jail over a hundred times, Kuti was single-minded in showing up corporate greed and political corruption. ITT, recognised by any Nigerian to be “International Telephone and Telegraph,” showed his sly wit. It was a pointed expose of the multinational’s CEO and the country’s dark involvement in various CIA entanglements.

TEACHER, DON’T TEACH ME NONSENSE (1980)

Wey dem no tell am, say him make mistake-ee

Say this yo, no be democracy…

Na for England-ee, I me no fit take over

I come to think about demo crazy

By the mid 1980s, however, Fela was described as a recluse. He stopped his train of interviews and lectures, instead choosing to stay in his studio. His political activism had not changed the landscape of suffering around him.

He began to question notions of education, asking where “teaching” came from. It begins at birth with the mother, but who teaches the teachers, schools, and government—how do problems like corruption, inflation, mismanagement, authority stealing, electoral fraud arise? To Fela, culture and tradition had become corrupted, and were infecting his people in a plague since England relinquished colonial rule in 1960.

BEAST OF NO NATION (1989)

How disunited is the United Nation

Human rights na my property-animal cannot dash me human right

Fela’s lyrics agitated over his country’s entanglement with what he saw as hypocritical global institutions. His albums "Overtake Don Overtake Overtake" (ODOO) and "Big Blind Country" (BBC) tried to expose how the various military take-overs in Africa were essentially the same types of dictatorship. However, in ODOO, he was able to expose the international collaboration and treachery involved in the killings of the young radical military leader of Burkina Faso, Captain Thomas Sankara.

Ironically, soldiers of the army would sneak into the Shrine under the cover of night to listen to his music. On his infamous Yabis Nights, he’d rib them mercilessly and they laughed right along with the civilian crowd.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

LADY (1972)

If you call am woman / African woman no go gree

She go say, she go say, I be lady o

Fela’s life cannot be seen without the women in it, or the accusations of sexism and prejudice. Yet he was a lifelong advocate of the sanctity of the African female role, which he saw as going under the parallel pressures of vain Westernisation. He once married all his 27 back-up dancers in a mass marriage (in a bid to “do right”). He later met his 28th, and last, wife in London, with whom he had two sons. His sons, also Afrobeat musicians, rejects these notions and remembers their father’s gay friends who stayed in their home.

In the latter part of his life, Fela’s spirituality became more apparent, as he spoke increasingly of animism, a core concept of traditional African religions. He started calling his music “African classical music”—which brought accusations of megalomania: “You wouldn’t expect composers like Mozart or Beethoven to write three-minute numbers, so why should I?"

On 2 August 1997, Fela Kuti died aged 58 of AIDS-related cancer in Lagos, Nigeria. He had refused all treatment from Western-trained doctors. Lagos came to a standstill after a million people packed the streets for his funeral. Abami Eda, or Chief Priest, as he now became known was a legend for Nigeria. Fela’s relevance, not unlike his music, is richly multi-layered and prophetic for many. Held every year in over fifty countries, Felabration celebrates his memory and introduces fans to new music. Fela’s brand of indiscipline is only becoming more relevant, as musicians after him, including his two sons, Femi and Seun Kuti, continue the art of Afrobeat, a colourful fabric for social and political commentary, allaying a people's thirst for humour, satire, and truth.