Home to a famous pub, The Wheatsheaf, the Fitzrovia neighbourhood of London is best known for its bohemian vibe and artistic class. It is said that this pub was where the Welsh poet, Dylan Thomas, proposed to his wife, Caitlin Macnamara, in the spring of 1936 while under the influence of alcohol. The pub was a cacophony of contrary voices in its heyday. Distinctive personalities that have been associated with this pub include Nineteen Eighty-Four author George Orwell, singer and dancer, Betty May, the openly bisexual Queen of Bohemia, Nina Hamnett, as well as surrealist poet and painter Phillip O’Connor.

Such spatial forks where words and craft crossed paths are seemingly things of the past due to new faceless communication systems. Yet, vital to a city’s creative success are nodes that make exchange possible. A true creative city is one that is formed through continuous dialogue and flexibility between its space and its people. The essence of creativity being this: seizing an existing idea and reshaping it into something new—the more exchanges there are in a single place, the higher the incidence of a revolutionary idea taking root. Creativity requires not just technical expertise or an imaginative approach; it also requires the right motivation. The intersection of these three produces art. Motivation is inherent to lived experience, and by facilitating not just a wider variety of experience, but also their interaction within its limits, cities can become birthplaces of creativity.

It is a simple ingredient in manufacturing. To make something more accessible, to condition creative habits, amalgamation is crucial. Technological hubs knew this, and made full use of it to encourage innovation. In a similar fashion, segmenting space in cities for artists to come together encourages creativity.

This begins from the city, which itself holds a place amongst the most spectacular inventions by mankind. It is natural, gregarious, for humans to work together, and cities aid that, pulling people from all its surrounds to a single locale where creative sparks can fly.

Despite the radiating pull of cities, communities gel on similarities, with each ethnicity nestling in their enclaves. A city of many ethnicities is not necessarily well integrated. Chicago, known for its racially diverse population, fares poorly on this count. The neighbourhoods of Washington Park and Woodlawn houses populations that are predominantly black, with a 2010 census showing a 97% black population out of 11,717 residents in Washington Park.

In contrast, cities with hallmarks of rich artistic tapestry—Sacramento, New York City, San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles—fared much better on the integration scale. Sacramento, in particular, was ranked America’s most integrated city in 2002, according to research by the Civil Rights Project and Harvard University for TIME magazine. This is not to say that art created with specific communities in mind are unimportant. But this sort of art is narrower, for creative dialogue tapers off under static, homogeneous conditions. Art is enhanced by the continuous influx of artists willing to interact with people of diverse backgrounds, to address various issues and communicate between communities.

Looking at these studies, integration seems to go beyond race, or any other easily observable classification. Diversity often falls along ethnic and religious lines, but what brightens the creative spark, and sharpens it? A good spread of socio-economic backgrounds, education levels, age, type of employment, sexuality and lifestyle is crucial as a standard for integration. What this means for cities is: by dividing populations according to differences, we reduce opportunities for creative interaction. A city that draws itself on racial and religious lines has not fully grasped what it means to be cosmopolitan. Lines project a clean and crisp image of the city, shunning the dysfunctional and unexpected.

.jpg)

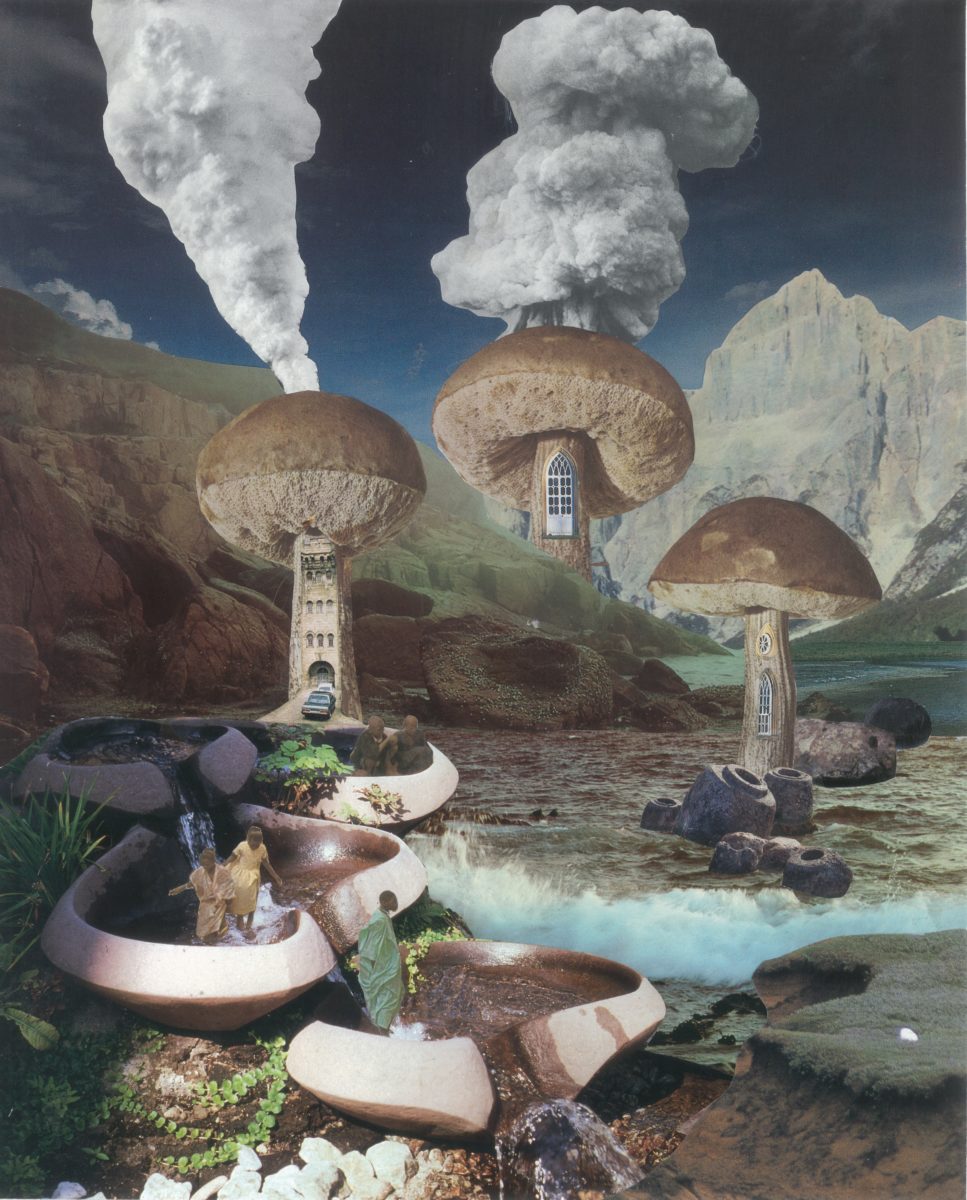

For a variety of experiences to come together effectively, attitudes towards practices that are generally regarded as dysfunctional have to shift. We have to devise a space in the mind to accept methods that enhance lateral thinking. One substance closely associated with this, by facilitating the connection of previously unlinked ideas, is marijuana. A banned substance in many countries, (a famous exception being Netherlands,) marijuana is commonly known in urban culture as weed or cannabis. Studies show increases in blood flow to the frontal lobe of the brain when taken, heightening brain activity.

It is in fact widely-publicised that the creative spirit is spurred by substance. Alcohol, opium and recently, marijuana have all been part of the mythology behind artistry. Hemingway and Van Gogh were both famously consumers of the green fairy, absinthe. With the psychoactive properties of substance stimulating the imagination, it is easy to see the links between its use and creativity. Even as we stop short of touting weed as a creativity cure-all, its beneficial properties as a stimulant are widely known to artists who depend on it.

In 2013, Amsterdam was ranked amongst Knight Frank’s top five most creative cities. Here is one city that takes pride in its strong drug subculture, but what is unclear is if this is the cause of its burgeoning creativity, or merely coincidental. There is the thought that if creativity cannot be nurtured by natural evolution, targeted enhancement comes across as a viable alternative. There is undoubtedly a case for legislation—marijuana is less addictive than nicotine; it is a drug that fulfills a function. Legalisation of weed allows accessibility and reduces long-term costs of acquiring the drug. While it cannot be said that the consumption of such substances is necessary in developing creativity, perhaps cities with more flexible laws in substance use do display the openness which allows the growth of artistic scenes.

The Netherlands, which seems to be the flag bearer for openness and inclusivity, was also the first country in the world to legalise gay marriage. Legislative changes too in the United States amongst other countries have shown an increasing awareness in issues of inclusivity, whether from changing principle or as a response to the voicing out by minorities. Marketing strategists have hitched a ride upon this exponential trend, formulating campaigns specially directed at gay people to capture the pink dollar. While it is debatable if it is the LGBTQ+ community who are being included, or just their wallets, research shows that the queer community tends to display better brand loyalty and more dollar support towards companies who have shown support for inclusivity. Nonetheless, markets in which LGBTQ+ campaigns are implemented tend to be more liberal in outlook, which seems to correlate to imagination and creativity. Acceptance in politics indicates a willingness to explore and understand diversity in art and culture, and cities which build that acceptance into their legislature are more likely to do so in their space as well.

Trends of acceptance reveal the inner nature of mankind. It accepts what it does know and what has been brought to light. It is not surprising then that legislation, which is the paramount seal of acceptance, lags for a considerable time behind norms. Progressive laws facilitate movement of people who value a culture of openness and inclusivity. The act of liberalization requires cognitive flexibility, creating a culture whereby obvious patterns of thought are discarded in favor of divergent thinking. This culture is, by default, a trait of the creative class.

Space needs people and people need space. Amongst other characteristics of truly creative cities are the presences of art platforms—magazines, exhibition spaces, theatre which serve an important role as outlets of expression for communities swamped by bread-and-butter concerns. Theatre and performance art forms are crucial as well in building a creative and accepting society, one where criticism is taken in stride. These platforms are our present salons, ballrooms and pubs.

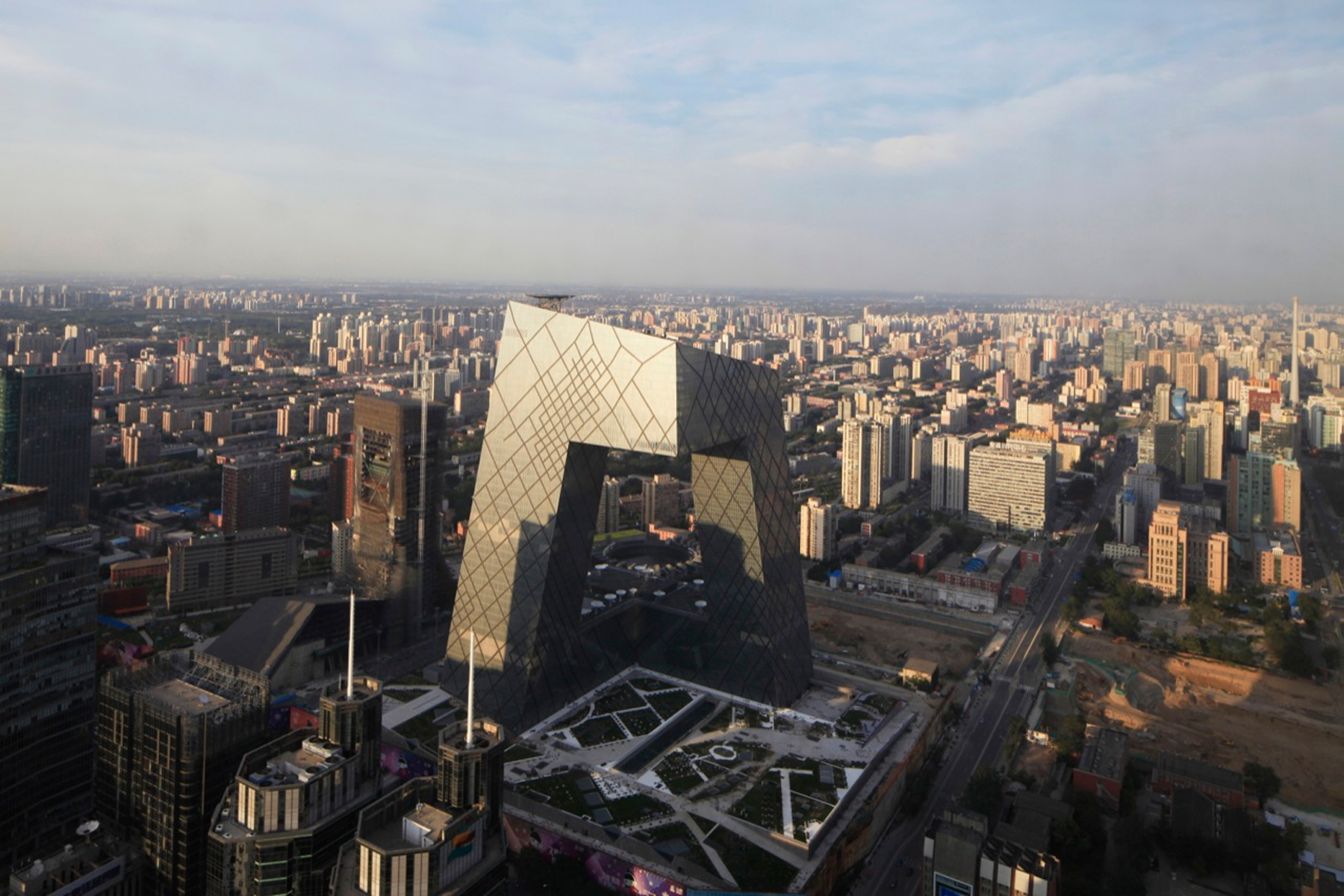

A city can cultivate its own aesthetic, have spaces for events and exhibitions, but without diversity on the ground to adorn its interiors, the value of the museum will not exceed the value of the compound. It can undoubtedly be well designed, have on board a team of renowned architects, and still fail as a cultural hub.

One rejuvenation which occurred in Bilbao, a Spanish town, has given rise to the condition, the Bilbao Effect. Seemingly successful, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, designed by renowned architect Frank Gehry, opened in1997. From then on, visitors have streamed in, revitalising the once doomed manufacturing hub and establishing its status as a cultural meridian.

Other cities have tried to mimic Bilbao’s success, but results have been mixed. Abu Dhabi, whose collection of museums on Saadiyat Island houses international brand names, Guggenheim (designed again by Gehry), the Louvre and a performing arts centre designed by the late Zaha Hadid, faces an oversupply, not of art, but of space. Without artists, an art space is nothing more than an architectural shell of a city’s hopes for an elaborate ground-up culture.

It goes back to the people, ultimately. Mental barriers are broken down by resolving physical ones. Creativity, an attitude fuelled by integration, liberalisation, and spatial assimilation, is not certain in diversified societies. A confluence of factors often result in hits and misses. What we know, however, is that cities can engineer creativity, and almost cyclically, the resultant buzz is sustained by creatives who are magnetised to the very buzz that they can create.