Where is the location of a work of art? This seems like a very stupid question. It’s in the gallery, on the canvas, in the frame or on the podium. Or, increasingly, it is in print or onscreen. In an influential 1935 essay, Walter Benjamin argued that the technological reproduction of a work led to the loss of its “aura”: meaning, the cultic value of its authenticity in place and time. Images are everywhere, but not everywhere equal. There may be endless copies, but ostensibly there remains an object out there that is the real thing.

With digital art, however—or memes, video clips, animated gifs, or digital images—there is rarely a real thing. These are simply files that are copied, shared, or altered in an endless circulation of users and consumers. “Where is a meme?” sounds like a koan. It’s everywhere and nowhere.

Hence, perhaps, the gold rush for “NFTs”—another of those new terms from 2020 and 2021 that we will soon wish we had never heard. Pronounced “niftys,” the acronym stands for “non-fungible tokens.” These are cryptographically-protected deeds, showing that a particular digital image or video has a single legitimate owner. You can view a clip of a LeBron James jump-shot for free, or you can pay more than $200,000 to watch it in the satisfaction that it belongs to you.

In a sense, NFTs solve the central problem raised by Benjamin—that of disappearing authenticity—in the most perverse possible way. Screw the art, let’s buy the aura. In fact, what we purchase with a token is ownership itself, and the object is mostly irrelevant. Somewhere in the beyond, John Berger (who famously claimed that museums exist to celebrate the simple fact of property) is smiling. The “art” could be the video of LeBron, or it could be an unimaginably rote and ugly image-array by “Beeple,” a collagist who seems destined to become the Leroy Nieman of the internet era. What is interesting about NFTs is that they have replaced the artwork with its mode of consumption, such that content is totally beside the point. The boosters deny this, of course. One of the touted benefits of NFT is social transparency, that records of ownership are open and freely searchable. But do you really want it on public record that you bought a Kings of Leon album?

To reimagine the cultural product as a proof-of-purchase is much like throwing out the painting and framing the receipt. “Concept” or “medium” or “meaning” become nostalgic terms for an object of increasingly purified peripherality. And it would seem that the worse the art, the more valuable it is likely to be—precisely because this puts the most daylight between the work and the blissfully unencumbered fact of its ownership. What seems clear, here, is that art (as an example of the commodity more generally) has entered a phase of radical doubt: how do I know that I truly own what I own?

"To reimagine the cultural product as a proof-of-purchase is much like throwing out the painting and framing the receipt. “Concept” or “medium” or “meaning” become nostalgic terms for an object of increasingly purified peripherality."

This outcome is not super-surprising, perhaps—after all, Benjamin argued that audiences identify more with the media of modern art than with any human content depicted. At the cinema, we are affectively bonded not to the characters but to the camera (the “eye” of which becomes our own). Tony Wilson, founder of Factory Records, said much the same thing about DJs. But NFTs do not fetishise the medium, so much as the mode of payment. This is perhaps why cynics have argued that the “art” here, is simply a high-cultural beard for underlying crypto-currencies like Ethereum: for money that is finally liberated from the frame of the nation-state. What is interesting about “non-fungible” art is precisely how fungible it is expected to be. Presumably, it is really bought less for affect (that deep, deep satisfaction of verified ownership) than to be resold for a yet higher price.

What should an artist do with all of this? It seems too simple to respond, as some have, with works of pure physicality. This is the case with artists Rachel Whiteread or Do Ho Suh, whose productions insist upon an irreplaceable instance of making. Certainly, the concrete mass appears as the polar opposite of the meme, or the digital work that can be indefinitely replicated. In the age of NFTs, however, such objects look a bit conservative, instances of a reflex rear-guardism.

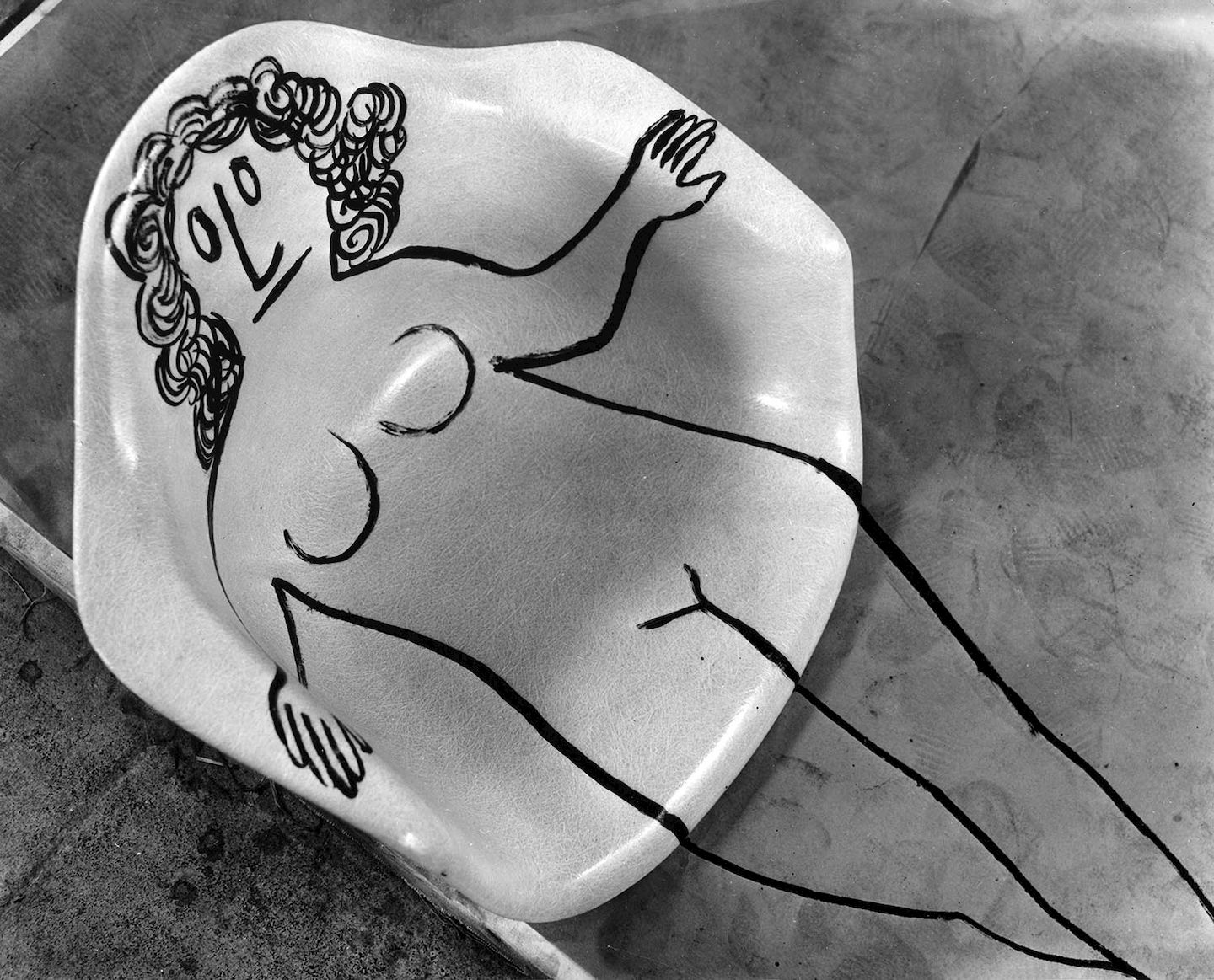

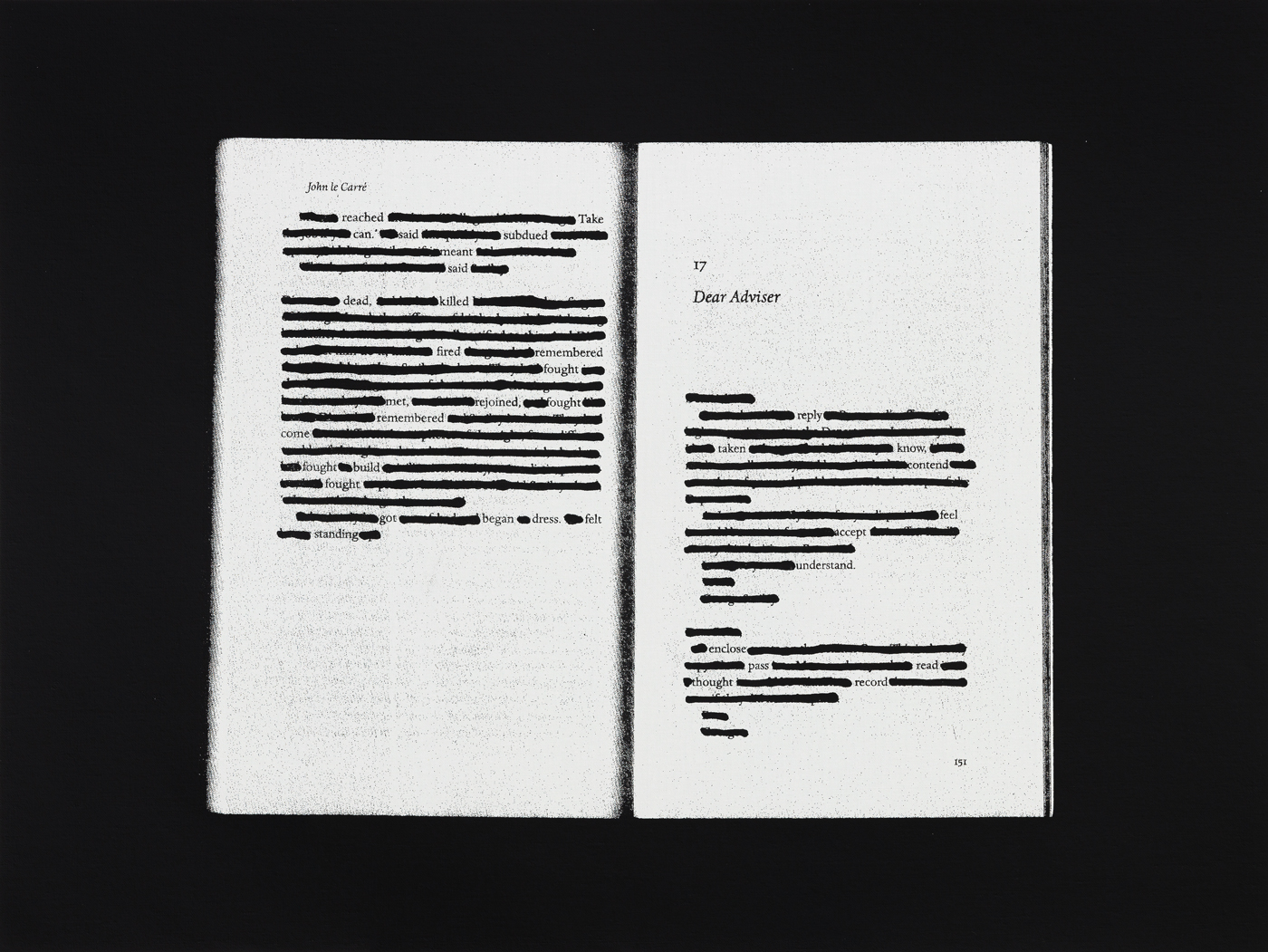

This is precisely where the output of Heman Chong, whose works are currently on show at Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI), becomes interesting—neither a fetishism of thingliness, nor a celebration of possessive alienation. The exhibition is titled Peace, Prosperity, and Friendship With All Nations; in case we don’t get the deadpan humor of the title, it is stenciled in an oozy horror-marquee font at the gallery’s door. As a refractory set of artistic devices, Chong’s collection finds another sort of resolution to the current moment: a sort of shell-game where the painting, the object, is constantly shifting. It’s at once right in front of you and fading into the media slipstream of some future-present.

In her catalogue essay, Kathleen Ditzig writes that Chong documents those futures that already exist. The ghosts of the anticipated and the non-arriving are here also, though in book covers unwritten and unread, redacted secrets never shared, diplomatic amity and a mythic pax Americana. The “real” work, while it hangs on the wall, always seems elsewhere: waiting in the departure lounge of a deserted airport, for a future that we were promised but never came.

Foreign Affairs (2018), for example, comprises UV prints on cotton and unprimed canvas depicting the back doors of embassies. These are violently repetitive (a theme of the oeuvre) and the images sag as they hang. There is a strange effect, in the cloth that stands for the impregnable buildings of an internationalist order, and in particular the back doors which cannot be seen now without thoughts of Jamal Khashoggi or the “enhanced” interrogation measures post-9/11. At the same time, the fabric reads as an intentional, no-fucks-given reaction to the recent fetishistic materialisms of the art world, or the uptight “rediscovery” of painting. These are more reminiscent of kitsch souvenir, like a Mona Lisa shower curtain. The work is slack—literally—and there’s more than a hint of the moral flexibility behind the diplomatic facade (its proximity to novichok and kompromat). This arse-backwards view of the global order is both funny and viscerally upsetting. True to form, Chong splits the curtains and invites us to walk through them in a way that feels seedy and against gallery etiquette. And also titillating, like the mental images that the title Foreign Affairs conjures.

Safe Entry (note the title) of 2020 is perhaps the work where this ambivalence comes into its most literal incarnation. These huge paintings—200 by 130 cm—depict active QR codes, repeated end-to-end across the canvas. These are rendered in maroon ink on a lurid peach background, a tone which we might pass for “skin” in the uncanniest of valleys. The paintings are grossly physical; the canvas surface has microfibers that recall unwanted hairs, and—in the kind of schlock-horror suggested in Peace Prosperity and Friendship—we approach a familiar digital icon to find that it has the imperfection and detail of organic tissue. The works in Safe Entry are looming. The inherent ugliness of the QR format, its visual vibrato, becomes more aggressive when magnified, and the result is a work of vague menace.

--2020--acrylic-on-canvas--200-x-130-x-3.8-cm-each.jpg)

Interestingly, however, the David Cronenberg-like aspect of Safe Entry in its imaginary of medium-become-flesh, is a ruse. At STPI, the visitors are busily scanning the codes, which lead to walking tours of a Changi Airport left empty by the Covid pandemic, another 2020 series by Chong titled Ambient Walking. These are haunting. And here, again, we feel the present-ness of Thom Yorke-ish future worlds, a kind of visual analogue of Brian Eno’s Music For Airports. Chong’s tours were intended for solitary walkers, house-bound by the virus—again, the imagery is merely the demonstration of a practice meant to take place via the body public.

It is hard to know, in this mirror-hall of Chong’s, where the “work” is. At the moment where the elephant feels most demonstrably present, it vanishes—becoming a referent that points to other locations and layers of mediation and presence. True to their inspirations in “social” technology, these all have the hyper-linked character of doors or portals. But unlike the NFT, which attempts to “fix” the infinite dupes of the online world with crypto-certification, Chong’s output plays in the space between the painting and its informatic afterlife.

The works in this show are undoubtedly “real”; we just don’t really know where their reality lies. They are not worshipful of materiality—Chong buys most of his inputs from a local art-supply chain where high-schoolers get their pens. He flirts with art as business, but is too smart to get lost in the carbon-intensive, libertarian porno theatre of the NFT. It would be wrong to say that the paintings and prints are “auratic.” They have ugliness, silence, unrequitedness, shame, as well as humor and longing; this sometimes feels like desperation and sometimes like a shrug. Either way, it’s a bit too personal and anti-heroic for art’s traditional modes of charisma. This is what made me want to look at the works repeatedly, and what makes them satisfying to see in person (like much good art, the catalogue pictures don’t do them justice). And discomfiting. Many of the projects—like a series made during lockdown—communicate the futility and distant hopes of an age where objects increasingly stand for both over-supply and remoteness. We must imagine Heman Chong happy; he is us.

.-performed-at-museum-macan--2020.-image-courtesy-of-museum-macan-(3).jpg)