On the first day of May in 2018, Lorde, the New-Zealand singer and songwriter emptied her social accounts leaving only two tweets on Twitter and three images on Instagram. The monochromatic image in the middle is a squared screenshot of J.R. Eyerman’s 1952 photograph of theatre audiences watching Bwana Devil with 3D glasses. This image, now iconic, is representative of debordian spectacle, following the French theorist, Guy Debord’s seminal and thoughtful predictions on social relations in the upsurge of mass media and consumption.

Social realms or socialities, as this text adopts, no longer goes by scant definitions of a gathering of two or more persons offline: a virtual presence suggests habitation, and however short-lived, to inhabit requires space. Realness is brought into view too. Social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson critiqued the digital dualist bias that marks life outside of virtual spaces as “real life.” What happens online is as much what happens away from the screen, they feed into each other and blur distinctions so frequently it is better to refer to them as one intermingling world. Identities, too, as an element of socialities also become more than what one individual constructs as a narrative of itself. Social relations inversely define us. In being with socialities, one value has been the promise of relating with the external world in ways that are vital and relevant to us. While virtual socialities bear semblance to socialising from pre-internet days, in that people still want to relate and be related to, not all social platforms engineer and optimise for social needs.

Nowadays, Lorde-leaving acts or attending declarations of dissatisfaction with virtual platforms beg the question of ownership, as their intentions drive the social spaces we choose to inhabit. Regarding a social platform like Instagram might manifest an I-told-you-so from Debord anxiety’s on declining social life under a pure economy of spectacle. On here, relations are mediated by images, performance through images and gestures; though this text will not veer into a short spiel on the authenticity of performance that happens online. Human relations have always been mediated by numerous ways of translating ourselves to others. This regards design and the kinds of relation it breeds. Nothing free comes without its costs; in Capital is Dead, author McKenzie Wark noted that “If you are getting your media for free, this usually means that you are the product.” The trouble with social platforms with a sole intent to sell, is its design succeeds after a motivation that optimises for sales. Sociality becomes so mired in this structural desire, that it loses meaning in the sludge of it all. The pure economy of spaces like Instagram enforces a limitation of activity, thereby, interpassivity. This unsurprisingly sneaks into relations within spaces producing a flux of media in such enormous amounts that supersede any reciprocal attention. To paraphrase Robert Pfaller, who coined interpassivity, it entails shifting activity from the subject to an object, in this case images and videos. What becomes of meaningful relations when the most you can do is look, like, and watch?

"Human relations have always been mediated by numerous ways of translating ourselves to others. This regards design and the kinds of relation it breeds."

Just as the isolation specific to the circuit breaker had nudged for a deeper reflection on what it means to gather together and be social, similar questions were asked of the digital. Alternatives exist and have always existed in game worlds and virtual nooks that have put more attention to socialities and social relation first—interactions thereafter are usually better for it. Nooks today include the likes of Discord built to accommodate niche communities of all peculiarities and sizes, or the nooks in temporary worlds of site-specific virtual art installations.

Enter Animal Crossing, a social simulation video game series developed by Nintendo. It is similar to long lineages of interactive PC video games; early 2000s games like Diner Dash, The Sims, and FarmVille come close as predecessors for today’s model. Minecraft as another example, was bought off by Microsoft from the indie studio Mojang, but still hosts socialisation for millions of players, ten years after its release. Space, of course, looks different in these contexts. For one you get close representations of a scenery—algorithmically or user-generated—and virtual landscape renders suited for social simulations. In comparison to the limited space of Instagram, it allows for more expansive ways of being online. Introverted people can flourish with subtler means of expression, a different kind of staying-visible than the spectacled visibility Instagram mandates.

Play is central in Animal Crossing. Through an avatar, a digital persona is suffused with personal styling. These digital bodies can stand as an extension of one’s individuality or a whole new experimentation around possible versions of themselves. Last year saw a global spike in players, due to the excess time required to be spent indoors. Collaborations happened with Nook St. Market’s fashion services, and with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by incorporating artworks from its collection. After the circuit breaker last year, Singaporean photographer Matthew Ng published a photo documentary on players and their Animal Crossing persona. One of the participants in the photo series, Jasmine, expresses how she extended her aspiration to be an Egyptologist by donning “Pharaoh's Outfit” and the “King Tut Mask while walking around Pocket Camp.” This small activity mingles with Jasmine’s AFK interest in Egyptology which is also pursued outside the game.

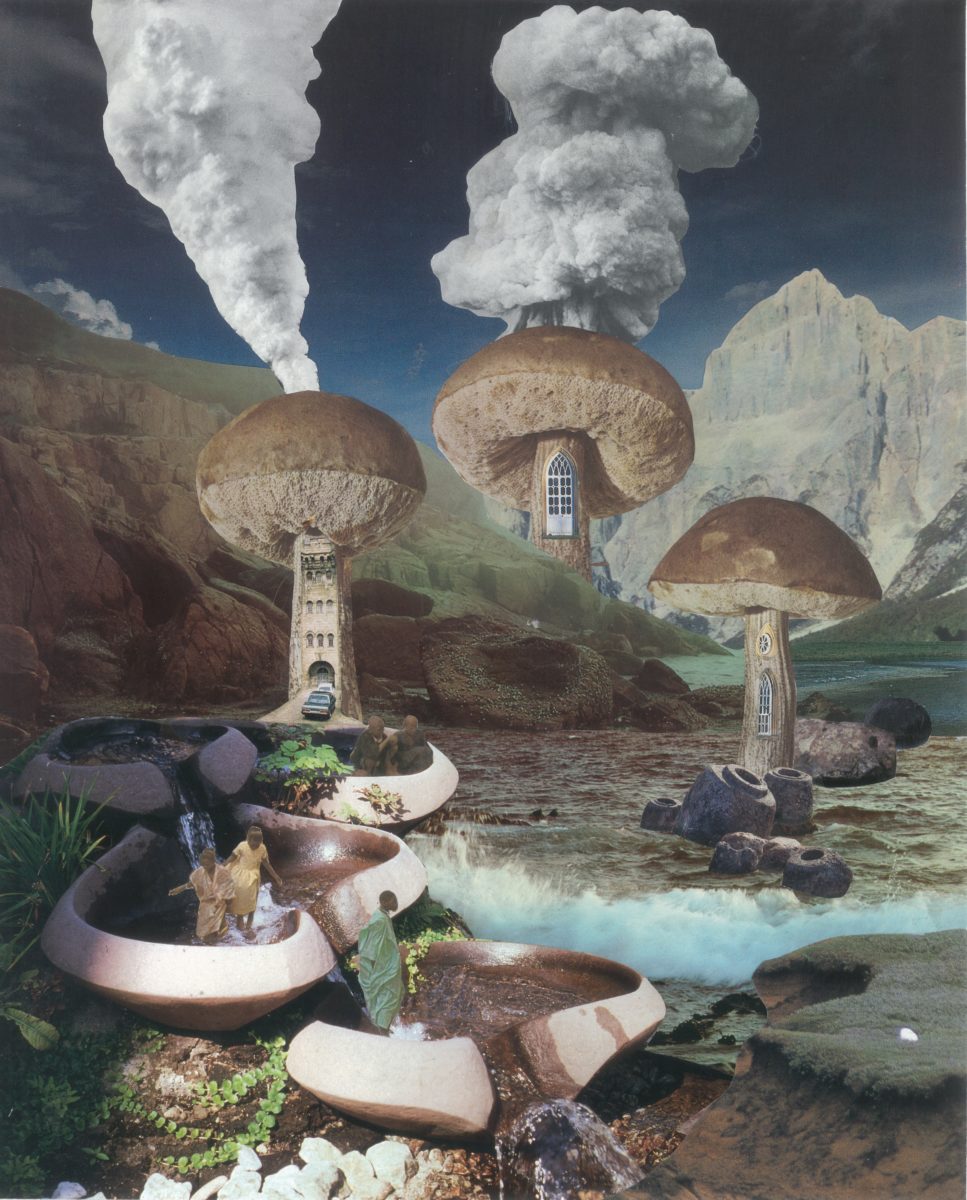

In thinking about the non-passive relations happening here, there are instances from the minute to the large. The act of designing your space—wallpaper and flooring customisations, furniture decisions, and do-it-yourself landscaping—and persona is an activity. So is setting your own goals, completing self-determined activities, exploring other spaces, apple picking. All these are great for one individual to explore around these given parameters—a point of relation within one person. Interactivity becomes prominent in world-building exercises. Actions extend to interactions by Animal Crossing’s feature of allowing users to visit other people’s islands. The option of multi-player interaction gives an added meaning to socialities: it can be played by yourself, as much as you want it to be, as well as play with others. Unlike games that provide only a mono-linear relationship with a player and their world, Animal Crossing stretches interaction under values of collaboration, gearing toward a feeling of togertheness in whatever community sprouts. The first image in this piece obviously indicates one world of its user actively expressing a side of their personal interest, which can in turn be a social space for other players. Dare we assume what this activity provided for this user?

Lawrence Lek said in an interview on the simulated world of his artwork 2065, a site-specific open-world video game for Singapore Biennale 2019: “Many media scholars compare the ludic space of play against the more passive spectatorship of cinema. But again, this boundary is never clear-cut, whether it's Call of Duty story mode, or Final Fantasy—you have sections of play and then you have cinematic cutscenes.” While alternative lives in any game worlds are not entirely rid of some variance of a pure economy, or the risk of passivity, it is tempered with many means of relations. It manifests as more than that. Across other social platforms, like Tumblr, there are indications of game worlds providing avenues for flexible creativity, where curiosity and unplanned discovery is possible. With this view, another life as an extension of bodily lives could mean more means of play and narratives designed to a large extent for respite and enjoyment. As the notions of digital civilisation and selfhood continue to develop, questions on terms of engagement will also continue to surface. What will always be important is that in space, lives can get to fulfil themselves.