"Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty." In 1933, novelist Junichiro Tanazaki published one of architecture’s most influential essays. In Praise of Shadows was a mere 73 pages, but the impact of its mindfulness, nuance and articulation of traditional Japanese philosophies within modern contexts are still felt today, far beyond its vernacular.

Of those it has influenced, whether explicitly or as part of its presence in Japan’s cultural consciousness, architect Sou Fujimoto is one of the most illustrious. Fujimoto has demonstrated a thoughtfulness towards lightness and light, restraint and elegance in countless designs including arguably his most controversial, the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion for 2013. And for fashion brand COS, Fujimoto exercises his considerations in the Forest of Light installation. Created for Salone del Mobile 2016, within a former theatre located in Milan’s San Babila district, Forest of Light is a poetic experience of light and sound and the ephemerality of sensory experience.

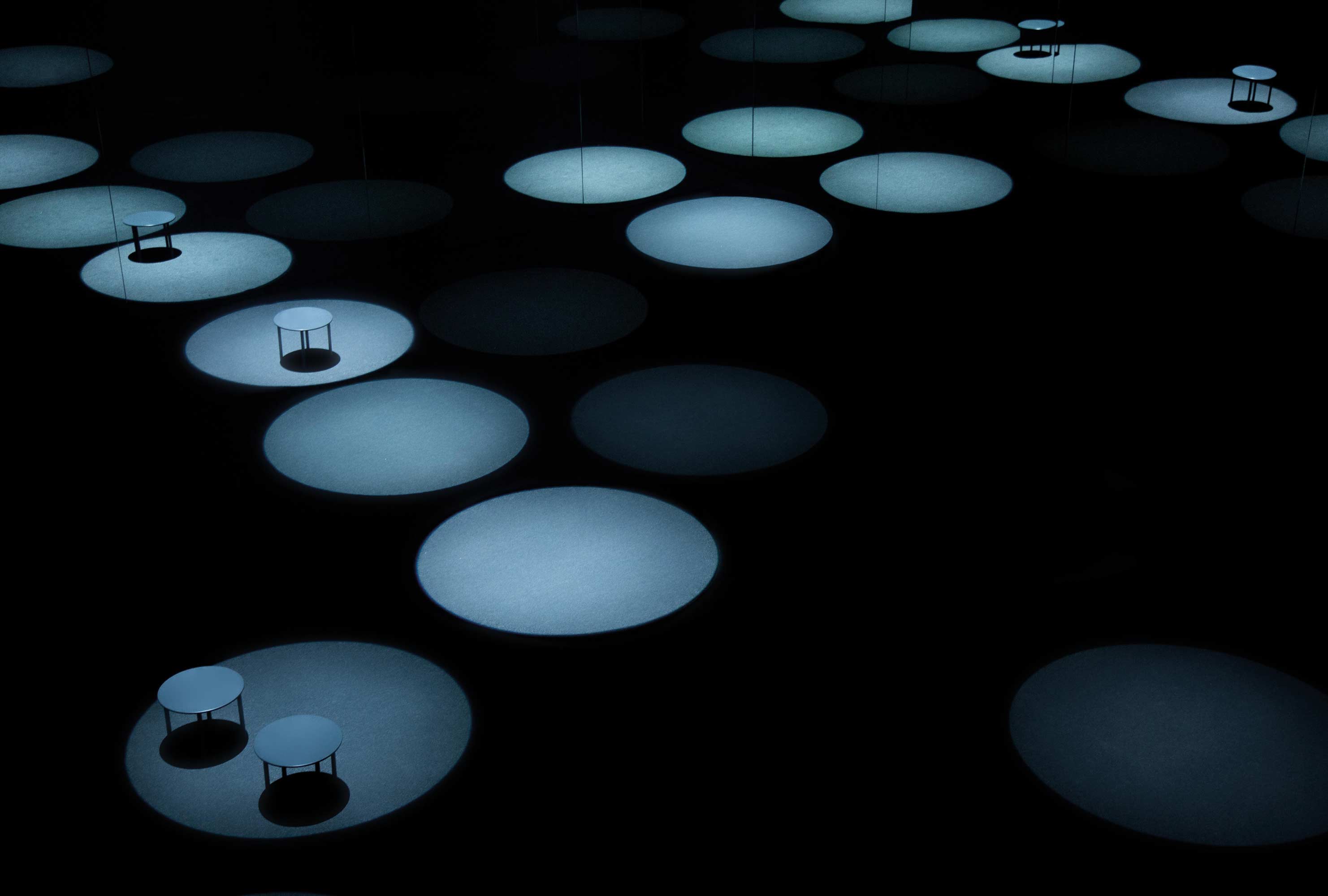

There is no other way to describe it besides experience; no physical structure is to be had, only a multitude of spotlights within a pitch-black room, creating cones of light that descend from its ceiling. And there is no other way to describe what you see besides a forest; the seemingly opaque projections of light are so strongly reminiscent of conifers in the morning mist, that standing amongst them fills you with the same sublime beauty of nature. Fog, entire walls of mirrors and a specifically composed soundtrack accompany the light, tracking and responding to the movement of visitors as they walk through.

Just as COS and Fujimoto himself have always displayed a belief in simplicity, Forest of Light is a simple, pure way to create physical experience, albeit without actual physical objects. It brings us back to a basic understanding of architecture, the interaction and consequence between people and space. The balance of light and shadow within Fujimoto’s installation is a quiet declaration that beauty does not need to be ostentatious, that contrast serves as well as excess.

And just as Tanazaki’s essay is a reconciliation of the traditional and the modern, Forest of Light makes use of technology to remind us of the subtleties sought in Japanese classicism.