“How would you summarise your life and work?” A friend casually asked while we were onboard the subway home. “Successes, failures, and milestones,” was my brief answer. I was close to revealing that certain objects acquired while travelling, too, formed cornerstones of my life and work. Think pebbled rocks from Seven Sisters Cliffs in Sussex or the stolen quenelle spoons that were meant for carving out little ice cream mountains by amateur and professional chefs alike. But I held back for fear of appearing overly sentimental or perhaps the embarrassment was too much to bear—knowing that my process of “collecting” might possibly be misconstrued as looting or even worse, the psychological peculiarity of hoarding.

Our conversation around work, objects, and one’s life recalled the work of the late American artist Pati Hill, whose life could be summed up as a fastidious accumulation of dreams, objects, and moments in the form of ephemera. Many of which—including xerographs, published novels, poems, sketchbooks, unpublished manuscripts, and letters—only surfaced after her passing. Hill was born in Kentucky in 1921 and did not undergo a formal art education. Art came into her life by way of poetry and publishing and her life was nothing short of vivid. She began modelling for fashion magazines and later went on to appear on the cover of French Elle in her early twenties. Later, she became friends with prominent intellectuals like the designer Charles Eames, photographer Diane Arbus, and novelist Truman Capote to name a few. Further scholarship on her archive, later uncovered much of her preeminent thinking, including a 1978 letter to Charles Eames which read: “What I will do will be important in the future.” 50 years on, Hill’s storied life and work is finally beginning to experience the critical attention it deserves. Whether her works are understood today from the lens of Proust’s extensive writings about objects and their associations, Hito Steryl’s oft-cited “poor image,” or nascent philosophical pre-occupations that ascribe existence to things and objects, otherwise known as objected-oriented ontology, Hill’s work is a trove of marvel.

That the objects in her work would invite such varied interpretations, readings and scholarship is no surprise. Whether or not they are intentionally ambiguous, many of her works reveal magical visions that trigger the imagination of each individual viewer. This is due in part to the intimate relationship she shares with the xerox machine, or photocopier, as her medium of choice. In Hill’s words, “I suppose I saw these sleek, brute, machine-made images as being art suitable to the time we are living in. A simple direct message from the forefinger that pressed the button that propelled the magic bar that illuminated every filament of the subject, and I trusted this message eventually to come clear by the even more dazzling light of the future time.” The immediacy and convenience that a click of the button confers to its user strikes a chord with what Hill was alluding to, but its significance bears further reminder. These comforts we take for granted today are what served as the medium for an unassuming Hill in the 1970s. Despite its capacity to create limitless copies however, its technology was imperfect and no two copies were exactly the same upon closer inspection. With its output inconsistent and resolution modest, the copier can be considered to be producing images that are, in all sense of the word, “poor.” Hito Steryl’s In Defense of the Poor Image (2009) offers an incisive probe into Hill’s xerography. “The poor image tends towards abstraction: it is a visual idea in its very becoming.” The meagre output and resolution of the copier is atypical to the richness of modern day high-resolution capture devices like large format cameras or HD television screens. Yet, in its modesty, the work seems to tell a more complex story than it could possibly capture.

"I suppose I saw these sleek, brute, machine-made images as being art suitable to the time we are living in. A simple direct message from the forefinger that pressed the button that propelled the magic bar that illuminated every filament of the subject, and I trusted this message eventually to come clear by the even more dazzling light of the future time."Pati Hill

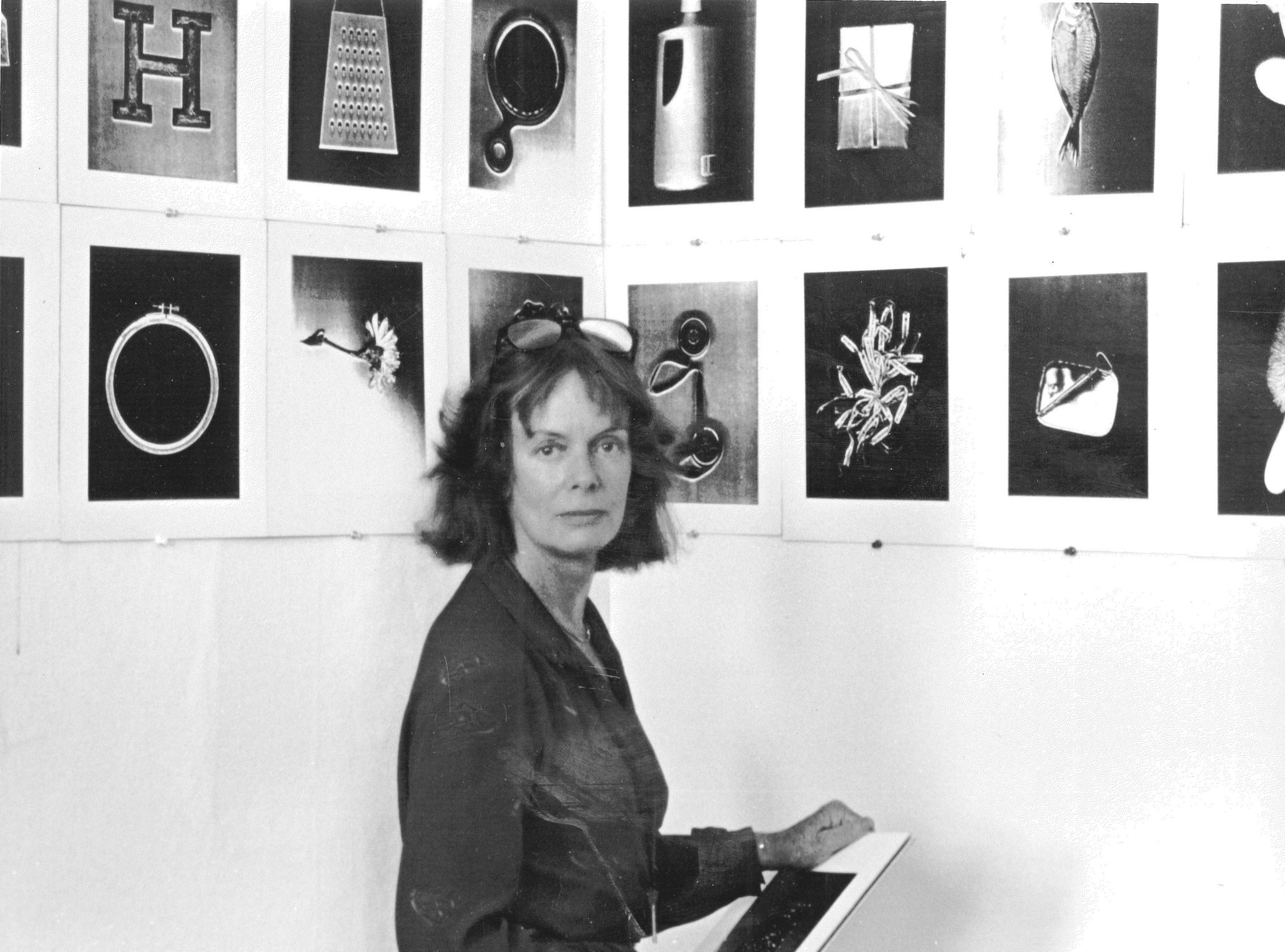

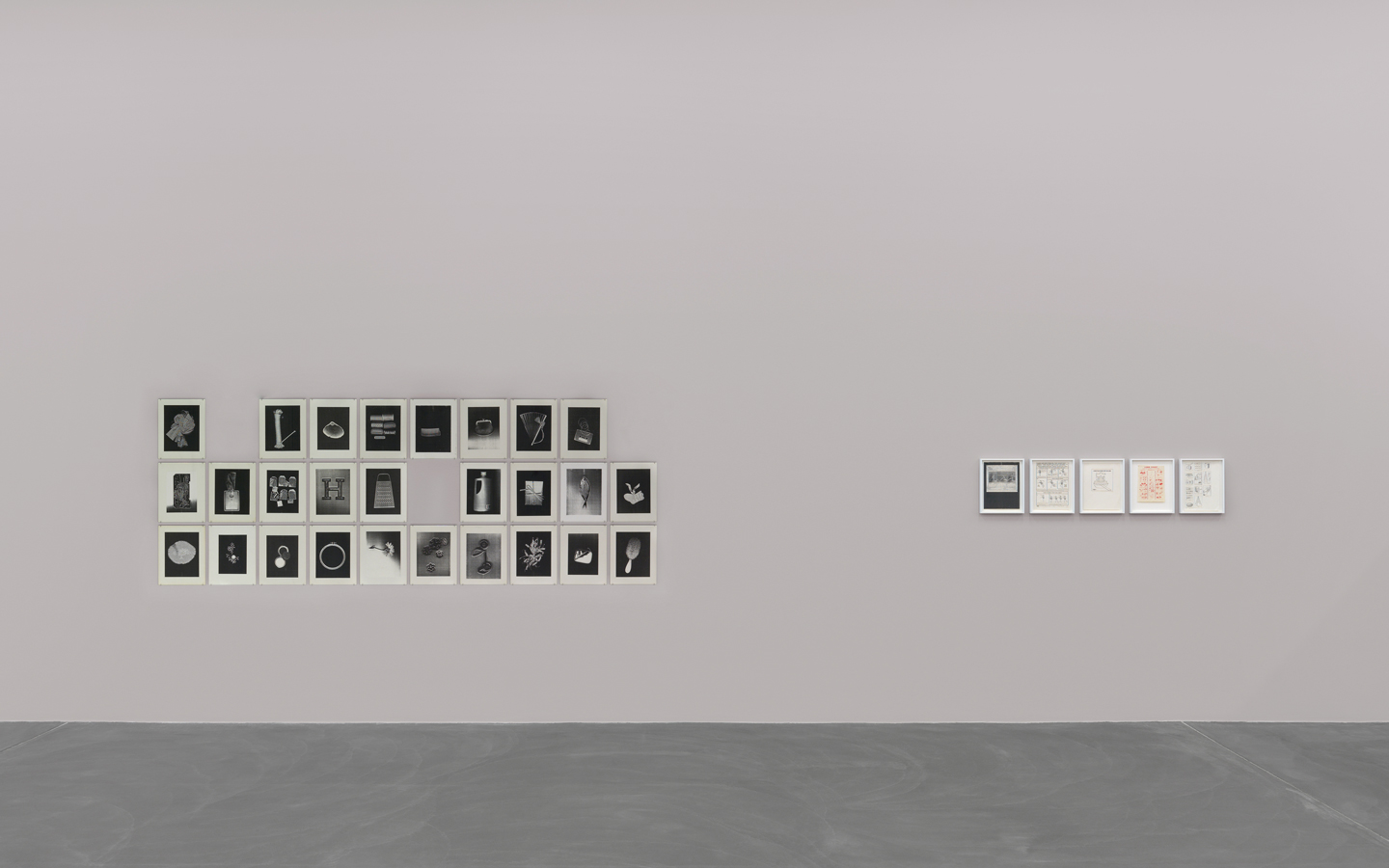

The 3-feet high, standalone duplicator that Hill first encountered in the 1970s “was simply the copier nearby.” She harnessed its potential for image-sharing and self-publishing to create Alphabet of Common Objects (1977-1979), one of her most seminal bodies of work. A pair of scissors, groceries, and many other everyday objects are depicted in this series of 45 photocopy prints made in a uniform fashion. Set against a dramatically pitch-black background, these objects are estranged from their usual contexts and possess a graphic quality that is characteristic of etchings and pencil drawings as opposed to mechanically generated images. While the work is the result of their verisimilitude of scale—the automatic one to one ratio established between the original objects she scanned and the resulting copier prints—the copier’s mediation imparts a peculiar effect on its output.

Distorted and disproportioned, it is almost as if the copier was indirectly telling us, this is how it sees the world across its glass platen. Contained within an 8.5 by 11-inch dimension of a typical US letter and coincidentally of Vulture Magazine’s page dimensions, the images speak to the viewer in a manner-of-fact way analogous with the documentary work of photographers like Taryn Simon or Singapore-based Robert Zhao—intentionally presented without any deliberate form of embellishment and stylisation. But if Simon’s genealogy of images in A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII (2012) aimed to showcase a more objective perspective that coalesced issues of inheritance, psychology, and power to reveal and uncover, Hill’s images lean towards subjectivity. They curiously conceal as much as they so evidently and eloquently reveal in its mystery. Against the abyss-like backdrop of the black toner, the objects magnetically beckon viewers to recognise and explore the enchanted secrets encrypted in their mass. The blurry contours found along the objects in some of Hill’s work from the her series Common Objects (1977-1979) even seem to exude a glow, an auratic quality that one might recall of a motion blur capture or Kirlian photography. In writer and art historian Francesca Ferrari’s words, it unsettles “the objects’ relation to space by emphasising their contours.” Seen in this light, the copier discloses the objects’ fantastic potential without obfuscating their own material in the round.

Courtesy Kunstverein München e.V.; Pati Hill Collection, Arcadia University; Photo: Annik Wetter

But this ghostly presence is suggestive of something more than mere spectre. Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in an Age of its Technological Reproducibility (1935) builds on this and argued for photography’s potential to materialise magical revelations by appealing to a viewer’s subconscious. This phenomenon of an enchanted connotation is what Benjamin coined as the “optical unconscious.” The camera, for Benjamin, goes beyond merely recording the physical manifestation of objects and people, it renders each subject with auratic and evocative presence. In this respect—and as Hill would have us see it—the relations we form with these objects are transformed and re-transformed as she produces these replicas through the camera or copier’s gaze. Technological devices like the camera and photocopier enrich human vision by imbuing objects with a magical quality even if these impressions vary from viewer to viewer.

But let’s say objects do indeed contain an aura, and dare I say consciousness outside of any humanly conceivable definitions of sentience, what would that mean and how does that change the way we interact with the environment and objects around us? What does my t-shirt think about being pressed against my body for prolonged hours a day during a COVID-19 lockdown? What does it feel about our intimate contact? And what of the broccoli’s fibrous body when interfaced with the cold steel of my brand new 7-inch santoku knife? Did that brief moment of contact spark joy (or pain) for either of them? On some level, this argument of an object-oriented ontology does strike a chord within art since artists themselves invest so much time and energy into imbuing objects with meaning. This understanding asserts a radical and imaginative realism that not only claims that things do exist beyond the purview of human conception, but that their existence is almost entirely incomprehensible to our human understanding. In Hill’s works, we see how physical objects are represented in a manner that reckons with our senses and experiences. They highlight the objects’ ability not only to reflect reality, but also fundamentally shape perceptions and identity within that same reality. Her works challenged the notion that things, objects, and articles can be stably defined and concretely described; they take on different qualities depending on how each viewer sees them. They are, in a way, the mirrors to how we see ourselves.