Sterling Ruby, the nihilistic, multi-talented American visual artist, may be best known

in the fashion world—especially amongst those in the menswear set—for his punky,

energetic collaborations with Belgian designer Raf Simons. Their co-designed

menswear collection in 2014, for example, seduced critics and consumers alike with

its beguiling, adolescent rawness. It was, as Simons has said, ‘the best-selling

collection’ in the brand’s 20-year history. Even before that, in 2012, Simons quite

famously recreated Ruby’s enigmatic spray paintings in the form of 3 gowns and a

coat for his debut couture show at Dior, turning those placid, silky surfaces into

moody, troubling gas clouds.

As accomplished as these stylish forays have been, however, they remain only a

small part of Ruby’s massive, polymorphous body of work. The man is so prolific,

and his output so varied, that his dabblings in fashion appear as a blip in his career:

a corner piece of an ever-intriguing puzzle.

Ruby’s work has been exhibited in a vast number of solo and group exhibitions from

New York to Hong Kong to Berlin, and in 2013, a painting in acrylic and spray

enamel fetched USD 1.8 million at a Christie’s auction—a record price for the artist.

He was featured in the 2014 Whitney Biennial and the 10th Gwangju Biennale, and

has pieces on display at the Guggenheim, MoMA, LACMA, the Pompidou, and the

Tate Modern. These days, he is based in Los Angeles, working out of a downtown

studio space—a four-acre, converted industrial complex—with a score of assistants.

Ruby was born in 1972, on an American air force base in Bitburg, Germany, to a

Dutch mother and an American father. At the age of 8, he moved with his family to

New Freedom, a rural area in Pennsylvania with a large Amish population, where he

grew up on a farm. Between New Freedom and LA, Ruby attended art school, first at

the Pennsylvania School of Art & Design, and then at the School of the Art Institute

of Chicago. It was only after reading Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s, an

exhibition catalogue from the Museum of Contemporary Art, that Ruby began to feel

the pathological pull of the West Coast. So he made the trek to LA in 2003, and

enrolled in the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena.

"A Sterling Ruby original is quite unmistakeable: his turbulent aesthetic extends handily across his work, and many pieces seem to be imbued with the embryonic quality of an ongoing experiment."Sterling Ruby

This move was his first point of entry into the world of fine art. At Art Center, Ruby

became the teaching assistant to Mike Kelley, an LA artist who worked in a crafts-based vernacular of ragdolls, patchwork, and screenprints. An approach that focused

on crafts held immediate appeal for Ruby, who was no stranger to the domestic—or

supposedly feminine—arts: he had learned to use a sewing machine when he was

13 years old, and he remembered vividly the prismatic Amish quilts of Southern

Pennsylvania and the quotidian utility of the wood-burning stove on his family’s farm.

These influences are apparent in all of Ruby’s works, with materials which range

from fabric and cardboard to metal and ceramics to urethane, bleach and spray

paint.

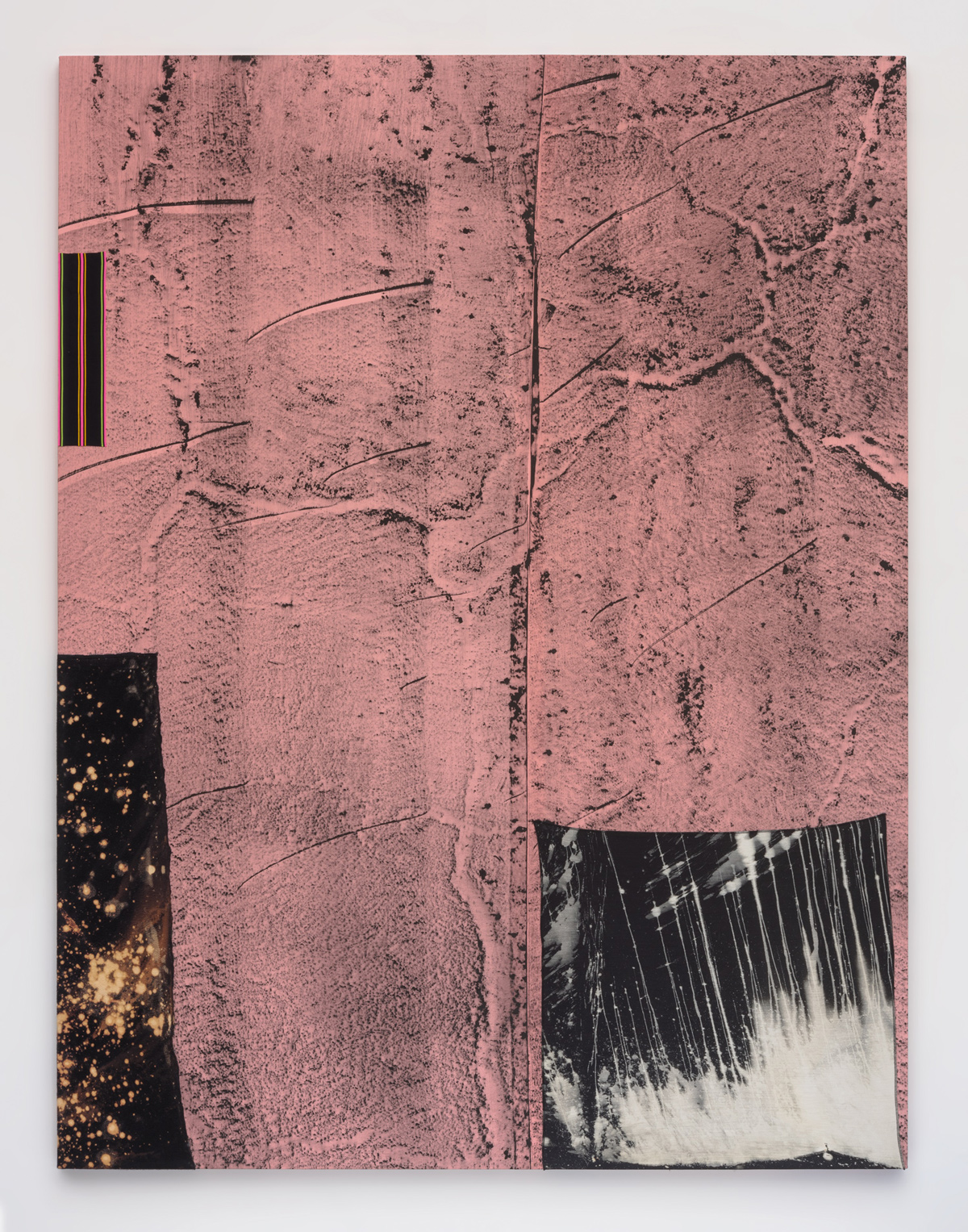

Despite the diversity of media in his oeuvre—which runs the gamut of sculpture,

painting, textile, collage, installation, photography, and video—a Sterling Ruby

original is quite unmistakeable: his turbulent aesthetic extends handily across

his work, and many pieces seem to be imbued with the embryonic quality of an

ongoing experiment. His shows often contain giant, mutated objects that appear to

have risen out of a toxic nebula, or a corrosive swamp. Frozen in time, their pieces

seem to be still coming together, alien and familiar all at once.

The clear-eyed continuity within Ruby’s work, as such, stands in brash opposition to

critics who have been suspicious of his tremendous productivity, his schizophrenic

use of multimedia, and, most of all, his commercial success. Running taut through

his body of work is a thematic thread that Ruby rigorously engages with, over and

over: ideas of utility and form, the hierarchy of objects, archaeology, and industry.

This is no more apparent than in his work wear series of functional garments crafted

from repurposed scrap fabric—leftover textiles from quilting, collage, and soft

sculpture projects— which were recently displayed in a London installation titled

WORK WEAR: Garment and Textile Archive 2008– 2016. (Those familiar with his

Raf Simons menswear collaboration will see an instant connection.) Each garment,

in addition to fulfilling its duty as a wearable object, also contains the trait of

indexicality: every drizzle of bleach or bloom of dye on the material is a physical

marker of its previous life as art-to-be. But it is when they are displayed as art pieces

in their own right that Ruby’s grand plan comes full circle.

By divulging his studio process of continuous unearthing and reassessment, Ruby has devised a traceable lineage in his own work that recalls, among others, feminist art and ‘femmage’ of the 1970s. These precedents interrogated the denigrated status of ‘women’s work’ in comparison to male-produced high art. 40 years later, such inquiries are still necessary. Ruby’s Bauhausian outlook aims to upend the snobbish hierarchy of value that permeates the world of fine art. To propose that fashion is art, now, can feel like such a stale proclamation; a fantasy of the juvenile fashion plate. And yet, in Sterling Ruby’s world—that is, the art world—to treat a paint-stained shirt and trousers as ‘art’ feels a little like anarchy. And somehow true.

.jpg)