The human consciousness is as old as written history, old as language, older still if we consider that articulated thought is not a birthright as much as an evolutionary development. Consciousness is a concept philosophers have struggled with for centuries, existentialism one of the most controversial and difficult subjects within academia. To be, something seemingly happenstance and instinctive, is a reoccurring cultural dilemma that we acknowledge but cannot seem to solve. The mid-life crisis and its younger sibling, the quarter-life crisis, have become an accepted fact of life. We joke about buying fast cars, infidelity, or abandoning all worldly concerns to embark upon a spiritual journey; regrettably, even as solutions seem to lie around every corner, self-fulfillment remains elusive. The widening reach of social media, our own coveting of lives ‘well-lived’ presented in infinite scroll, and the pressures of society, tradition and culture see us become the people we think we should be rather than the people we truly are.

It is not a fault; it is simply the way we function. Philosopher Martin Heidegger’s debut scholarly publication, Being and Time, puts forth many invaluable propositions on existence and relativity. To be philosophically inaccurate and entirely colloquial, Heidegger’s work presents the idea that we exist not as a singular being, but always in relation to the world and its concerns. As much as we understand the world from our relative position in it, the world acknowledges us by our presence in and relevance to it, which translates into our influence on the human experience at large. This is the determination of newness: not only must we be innovative, but also relevant. Countless ideas and idealists have fallen at the wayside, less for a lack of brilliance and more because the zeitgeist was not ready to accept them into its contemporary cultural landscape. Behind every success story is rejection; doubt and skepticism are most often expressed over chances of market acceptance than systematic irrelevance.

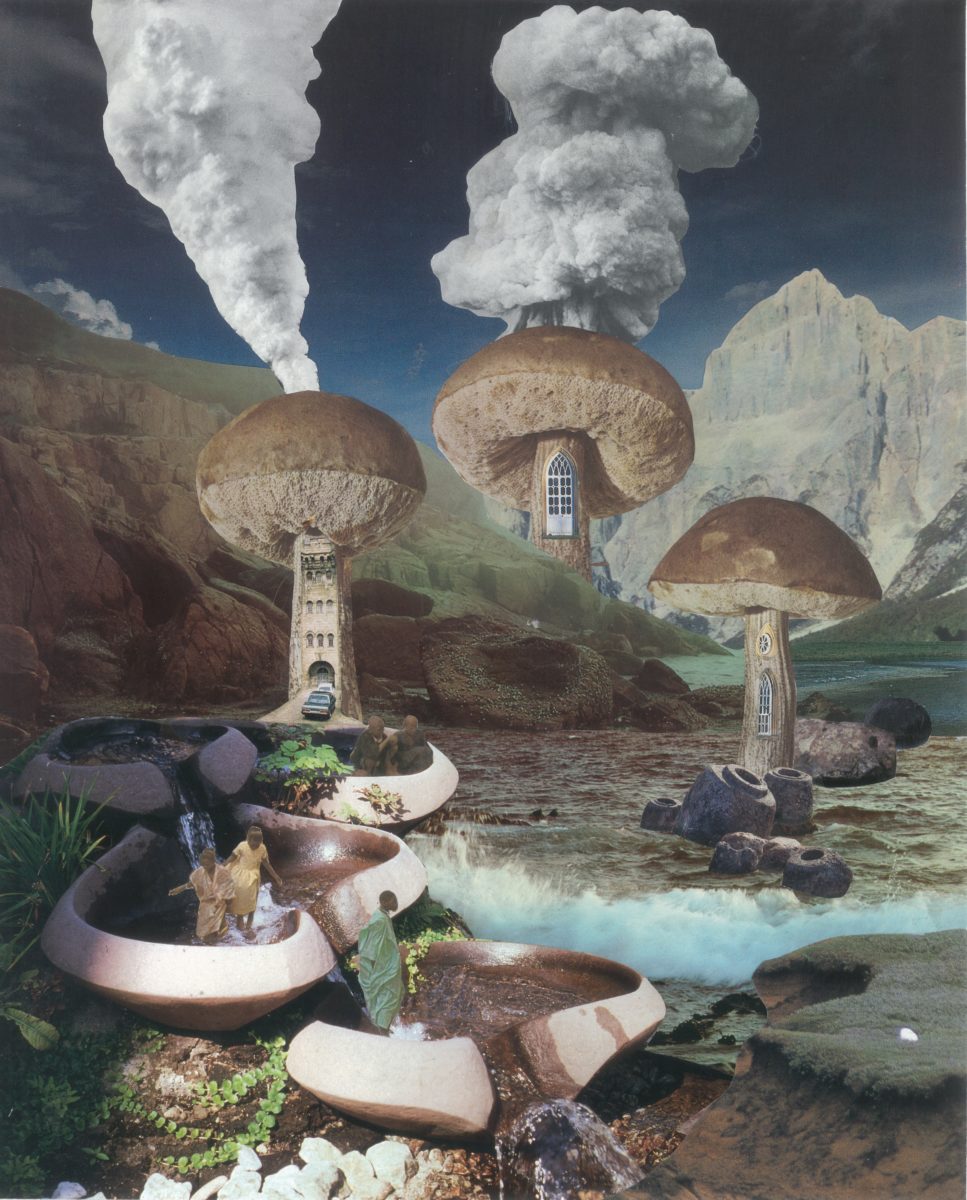

In marketing and in being, we feel the constant need for restraint, our desire to belong causes us to cut ourselves down until we fit in a box. Every teen movie ever has some sort of message about breaking free from the shackles of popularity, that to be happy we should just be ourselves. Our new mantra for this decade is to ‘live the best life that you can’, but what life is that? Is it a life we create, or a life we feel obliged to act out? We are at a tipping point, where possibilities of that ‘best life’ are so numerous, but an entire generation is defined by their lack of direction. The mores of our age may dictate ‘you must go to college’ instead of ‘wear this corset’, yet the impetus is the same: to create a culture that is largely homogenous and affirms the values of society. Except, instead of primarily enforcing strict gender roles and class division, contemporary society opines a need for STEM experts over anthropologists. We strive to be relevant in an age where opportunity is widespread, but does not necessarily mean freedom, and this extends to our creativity. Relevance is not solely conformity, it is also evolution along a predictable trajectory. We praise the latest fashion cycle for its daring, or a new building for its complex organic structure, but really, did we not see them coming? When shock and subversion become normative, and innovation loses its meaning, creation becomes less about making and more about repetition.

The one thing that truly determines us is our selves: our history, our emotions, our opinions. Not the clothes we wear, nor the art on our walls, although these things are expressive. But there is a difference between expressing to reflect and expressing to imply your sense of self. Through the visual clutter of social media, traditional media and the increasing focus on ‘aesthetic’, it becomes difficult to grasp ourselves and parse the difference between expres- sion and projection. The only way to separate these is to examine ourselves, our wants, our beliefs and values. Trite as it seems, introspection helps us to rediscover ourselves and find the best way for us to engage with the world.

The popularity of Kinfolk is one of the most fascinating considerations in publishing. How did this magazine, a manifesto for slow living, gain such an obsessive following in its short existence? Beyond the glorious photography and relatable writing, perhaps the greatest factor behind its success is in the introspection it inspires. By imploring readers to slow down their pace of life and appreciate the world around us—nature, details, our relationships with other people—Kinfolk is teaching us to reconnect with the things we value, and more importantly, the reasons we treasure them.

"In order to understand the world, one has to turn away from it on occasion."Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

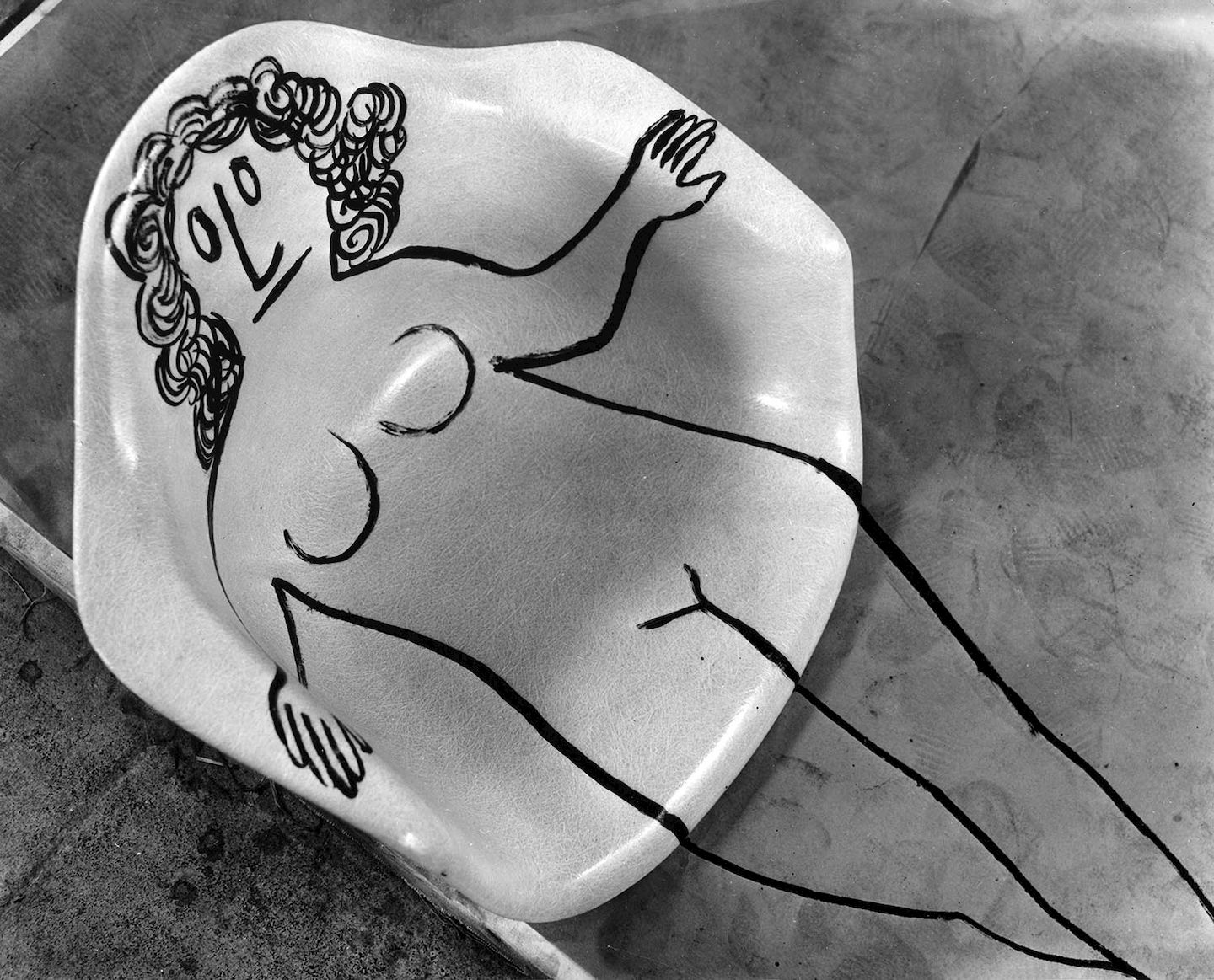

The journey to find yourself is not one embarked upon in isolation; nothing exists in a vacuum after all. As Heidegger enunciated, the self is not an object, but also how that object exists in the world. It is more important to our self-development to understand why we appreciate art, rather than the styles or mediums of art we favour. Establishing the ‘why’ creates a personal philosophy that engages our experiences; the ‘how’, ‘who’ and ‘what’ will naturally follow.

That is the nature of philosophy. A study of the fundamental, innate problems of existence, morality and knowledge. To be introspective is to be a philosopher, not of the academic understanding, but of ourselves. Having philosophical consideration of who we are leads us to reconcile our past and determine a pathway for the future. Instead of creating a static façade, it creates a system that is applicable across numerous concerns: our relationships, our social movements, our artistic integrity. It allows us reassurance in our work, affirming that we are not simply conforming to an expectation but creating something that is truly of value, even if that value is only apparent to ourselves.

Renè Descartes’ most famous philosophical proposition, cogito ergo sum, articulates the foundation for truth. We think, therefore we are. Truth comes from within. But we often forget that there is a precedent to the phrase: dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum. I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am. Doubt stems from a subconscious dissociation or disagreement with the world; it is by introspectively meditating on this doubt that we find our way to truth. And it is our truth, not some lofty ontological objectivity that ultimately matters. We are but human, the most miniscule speck in the path of human existence. But we are also human existence itself; each life lived invaluable because it is irreplaceable and unreplicable. Do not be deterred by the fear of seeming irrelevant to the world; true loss occurs when you become irrelevant to yourself.