When Daniel Arsham was a child, his house was destroyed by a hurricane. This life event seems to have been seminal for the multidisciplinary, New York-based Arsham, whose work recurrently explores notions of decrepitude and destruction. Arsham's sculptures look like 20th-century archaeological excavations uncovered far in the future: "I'm taking the past and jumping over the present into the future," Arsham says. "You don't quite know where you are in time."

In this exclusive interview, Vulture speaks to Arsham about the conceptual and psychological underpinnings of his multidisciplinary work in sculpture, architecture, and dance to better understand his unique artistic output.

You recently premiered your Future Relic series at Art Basel. The title is a peculiar oxymoron that juxtaposes the tension in time. What is your relationship with time and what are your thoughts on the future? How do you relate to the ‘now’?

Time for me is something that in many ways comes out of my works, the paintings that I do. For many years I made paintings that in some ways floated in time. The subject matter often depicts architectural constructions in picturesque natural landscapes. The architecture within these landscapes was often sort of purposeless, or kind of functionally undefined. Meaning, you would look at it and not necessarily know what the architecture was for, although you could tell that it was manmade. And I always resisted placing figures in these paintings because I felt that it would link the image to a specific time period based on what people were wearing or how their hair was cut. So removing figures from these works allowed the pieces to float in time in some way. I’ve always had a particular fascination with the future and in some way the potential that can exist in the future.

How did you decide on your choice of ‘relics’? Do you have a private relic of your own?

I spend hours and hours trolling Ebay, looking for these things from the past and I’ve often said that Ebay is the contemporary library of Alexandria. Every single thing of human existence can be found on Ebay, it’s this treasure trove of material from the past.

You categorize your works into “dimensions” as you move through different media. What prompted you to move into the realm of film, and what new dimensions has film opened for you compared to dance, architecture, sculpture and painting?

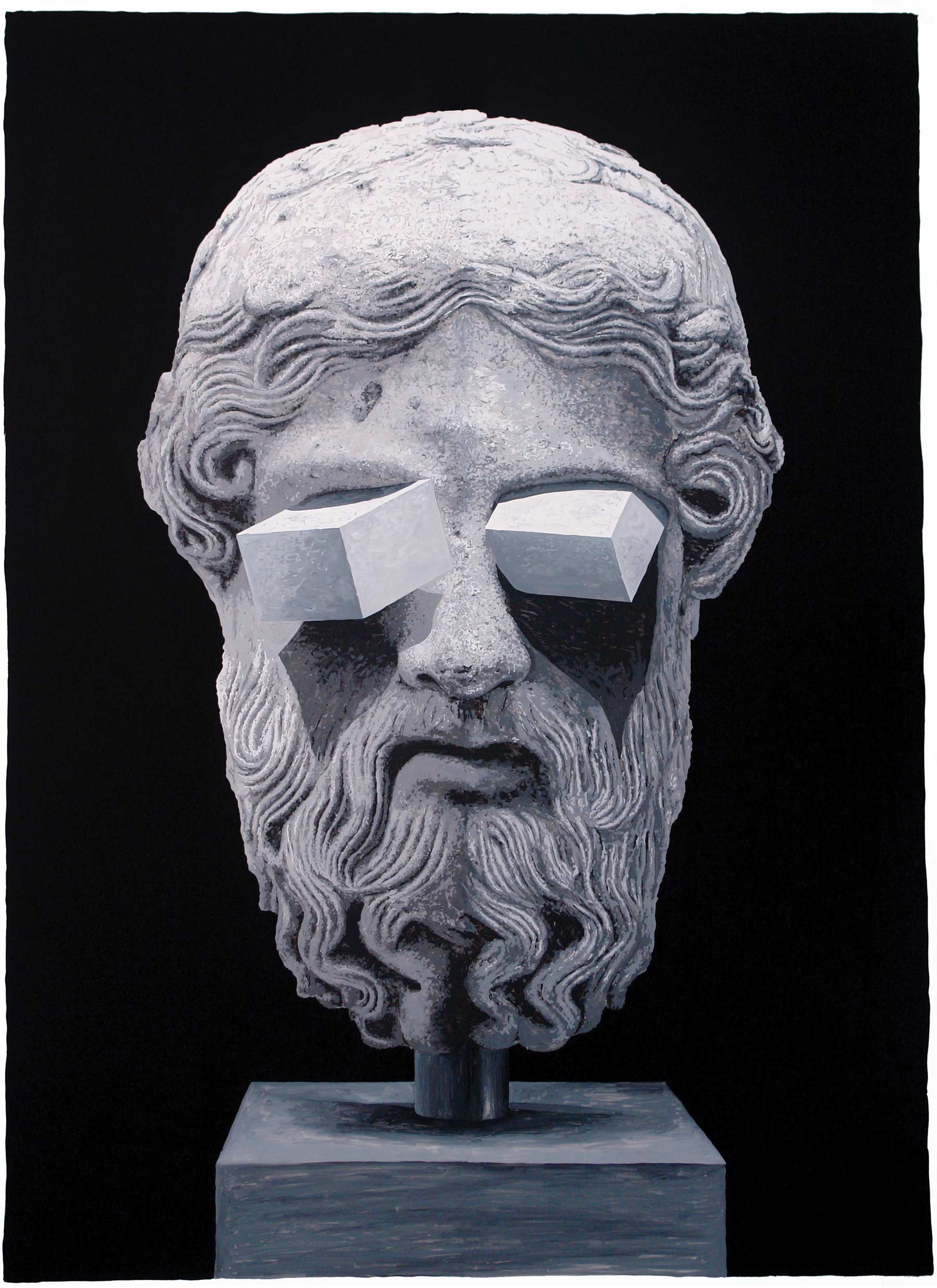

Much of the work I’ve done over the past few years involves this notions of taking objects from the past and reforming them in materials like volcanic ash and crystal to project them into the future, as if they have been uncovered on your archaeological site in 1000 or 10,000 years. I often wonder, when people view these works, what kind of world they are imagining. It occurred to me that I can control that vision, I can sort of create a narrative around that.

The Future Relic film series is really about creating a story, a future around this piece. Obviously I’ve worked in many different disciplines and in some ways they kind of all feel the same to me in the end. They are executing a particular idea or vision within a certain set of tools or mediums. For me, it’s often about finding the right collaborators to work with on projects like these, other designers, musicians, fashion designers that can help me execute the costuming.

The world you invoke in your film seems to be a post-apocalyptic one. It is haunted by the spectral aftermaths of disasters. I understand that your experience of Hurricane Andrew had a huge impact on your work. Was this series a way of exorcising ghosts of your own?

I don’t necessarily see it as a post-apocalyptic piece. Something has occurred in the future; if you were a Native American living in New York, Manhattan Island 1000 years ago and you envisioned yourself standing in the middle of Times Square, in the future, what would you feel? It’s a completely different universe that I’m trying to create, that is in some ways a fiction, but also taking things that we sort of know, that use everyday, and projecting them into the future. Everything that’s ever been made or created: architecture, cameras, telephones, bottles, computers, all of these things they will never go away.

Nothing that’s been made disappears. These things exist forever and in some way I’m using that idea in the works. I don’t think that this is necessarily a way, or has any relationship with my experience with the storm.

How do ruins inspire you?

I’ve always had a particular fascination with ruins. I visited Chichen Itza and Angkor Wat, the ruins in Easter Islands and the Moai statues. This kind of archeological notion of looking at the past and generating a story. Archeologists are tasked with pulling things from the past and creating a story so sometimes when I’m making these Future Relic films–when I’m writing the script–I’m trying to forget everything that I know about now. I try to look at one of these objects and pretend like I’ve never seen it before, as an archaeologist would and see what story I can generate, what world this object comes from, how it is used etc.

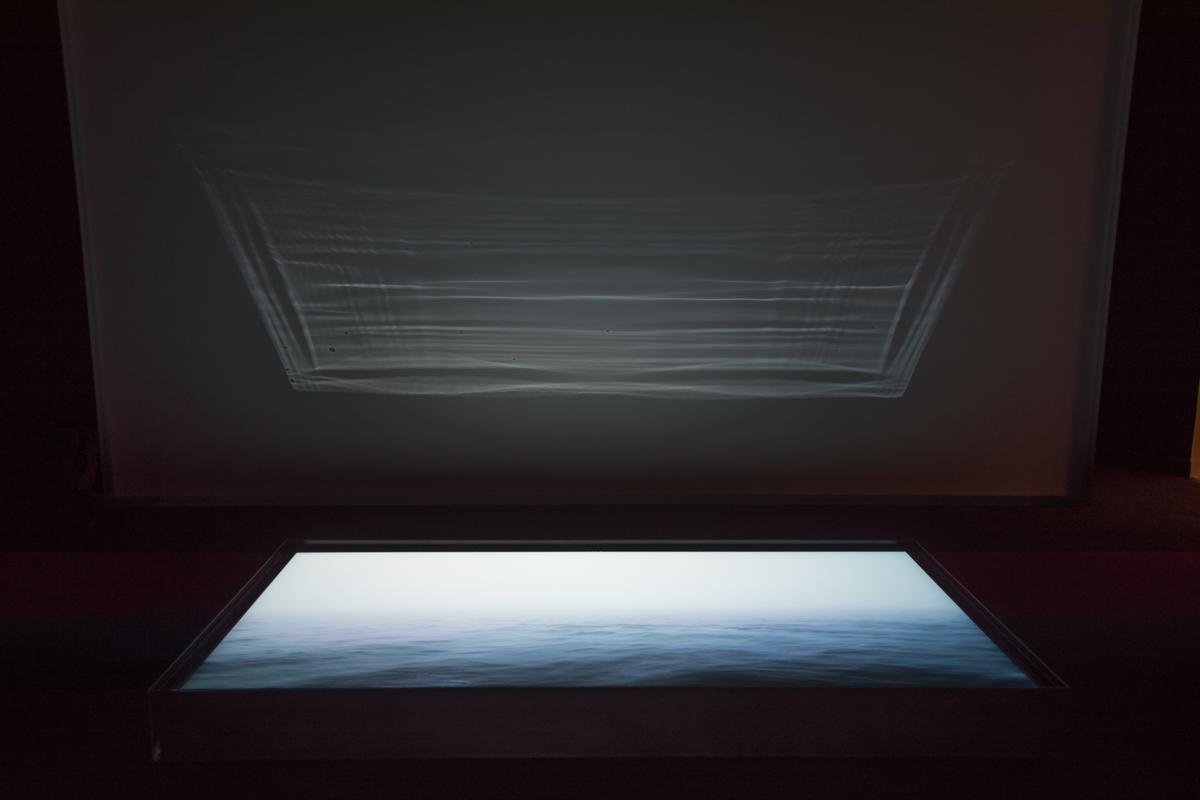

Many of your works dwell in the realm of the uncanny, in the specific commingling of the familiar with the unfamiliar, whether it is making the ‘present’ uncanny with future relics or through the juxtaposition of materials with your ‘fabric walls’. What are you hoping to achieve through your deployment of the uncanny?

I think that the uncanny does play a large part in what I’m creating, not necessarily intentionally. Anytime you disrupt the everyday, anytime you take things that people have a familiarity with and shift them not drastically but very subtly, this is when you can provoke a feeling, a reaction, an impression in an audience. My work is not about prescribing a certain idea or vision, it’s about generating possibilities or potential scenarios in which a viewer can project themselves.

What is most uncanny to you now?

Even these future relic objects and many of the other creations that I am engaged in have an uncanny quality. Taking a basketball and re-forming it in volcanic ash as if there had been some scenario in which this thing had been compressed and sort of re-formed–when I think about the ruins of Pompeii, these figures that were calcified and turned into ash in a second–in some ways I’m generating a story out of these objects, and sometimes that story can certainly provoke strange feelings.

Why the obsession with architecture and babies?

I think this question (about an obsession with architecture and babies) comes from a quote that I was quoted in once, where I said that the two most important things–gestures–we can make as humans are making architecture and making babies, and what I mean by that, is that our children, our future, and the way they carry and inhabit it (is important.) The world that we create is their world, their future; architecture for me is the most permanent, lasting gesture that I see we can make. Art, any other sort of cultural expression is in many ways very ephemeral. Architecture often lasts a very long time.

How has your work with dance inflected your understanding of architecture? Might architecture be more ephemeral than dance?

Dance is probably the most ephemeral art. This is something that Merce Cunningham often talked to me about when I worked with him–about the sort of sensation that dance is an idea. It’s encapsulated in the moment of the performance, but it doesn’t ever exist. You can’t say that dance is a thing. In some ways it’s quite similar to music. Although music can be recorded and played back, it’s a simulacrum of the experience of live musicians playing–but dance is something that really doesn’t exist, except in the moment that you’re viewing it.

Do you have any daily rituals? What do you do when you want to escape from your work?

I’m in the studio every day, and my work is my practice is my life–everything is bound up together.

What is the most decisive way in which chance has played a role in your work and process?

I think it’s often the opportunities that I come across in my world and what–who I meet and how I’m presented with potential projects, opportunities, this is really where chance comes into play.

You have become a very prolific artist at a relatively youthful age. What failures have you encountered while embarking on this journey?

Plenty of failures, the vast majority of them occurring in the studio. And in some ways, all of my work is about failure–the idea that nothing is really perfect or lasting. This is encapsulated in these objects from the future. There are breaks in the material, things are eroding and decaying, nothing is permanent and lasting.

And I think in a more practical sense there’s a lot of trial and error in the types of work that I make because I’m experimenting with materials that are not typically used in art-making–volcanic ash and crystal, and glacial rock dust. How are these things formed? A lot of these things are a process of experimentation, trying to find out how I can refine these things into objects that have potential for meaning.

Returning to the theme of future archives, what advice would you now give to your 23 year old self? What would you like to remind yourself a decade from now, to your 43 year old self?

Certainly the Future Relic film series is a massive endeavor of mine. I’m very excited about it and its new avenues for me. So when I’m creating paintings or sculpture or other things in the studio I’m also thinking about the props that are also going to be used in the film. And I’m afforded a free license with these objects because in many ways these props have to exist for a very short amount of time. They can be made differently. I can use materials like ice within the film.

I’m not a believer in fate. I believe in my own sort of will to do and make things happen. So I would tell myself to continue to do what I did.

I would probably tell (my future self) to remember to keep time to paint. Painting is the most time-consuming of my practice and really the only part of my practice that’s solitary. In all of the other aspects I often have other collaborators but painting is really at the core of my practice.