Generations after the idea broke into the popular imagination, the starving artist remains a familiar, recognisable character. This trope’s remarkable longevity suggests a kernel of truth—that then, as now, artists tend to face considerable economic insecurity. Taking a candid, sobering look at the underlying reasons for this is Sookoon Ang’s 2019 documentary Living for Art, which examines its subject through conversation with artists, and other figures of the art world.

When looking for the causes of this insecurity, one all-too-common practice comes to mind as a possible explanation: the ubiquity of having “exposure” proposed as adequate compensation for artists. In the experience of the artists interviewed, this may take the form of literally being asked to work for free, or, in a less extreme form, for sums altogether incommensurate with the scale of the projects proposed. These might be sums that sound attractive, considered on their own—but when reckoned in terms of the hours an artist puts in, may turn out to be meagre indeed.

It’s a practice by no means restricted to new and emerging artists—in one particularly telling example, Amanda Heng recalls one such encounter: “These people said that they're not able to pay artists' fees—I found out that they had a budget for all other expenses except the artists' fees. So I had to tell them off.”

In the experience of the film’s subjects, this pervasive logic of under-compensation is not confined to one-off fees. Grants, subsidies, and other such initiatives certainly serve to get money to artists, but also come with their own specific limitations and blind spots. As Susan Gloudemans, Director of Strategy and Development of the Rijksakademie Trust Fund Foundation, puts it, “There is not a wage for artists—there is a subsidy for artists. There is not a basic income for artists, but there is support for artists. And what does this say about how we value art?”

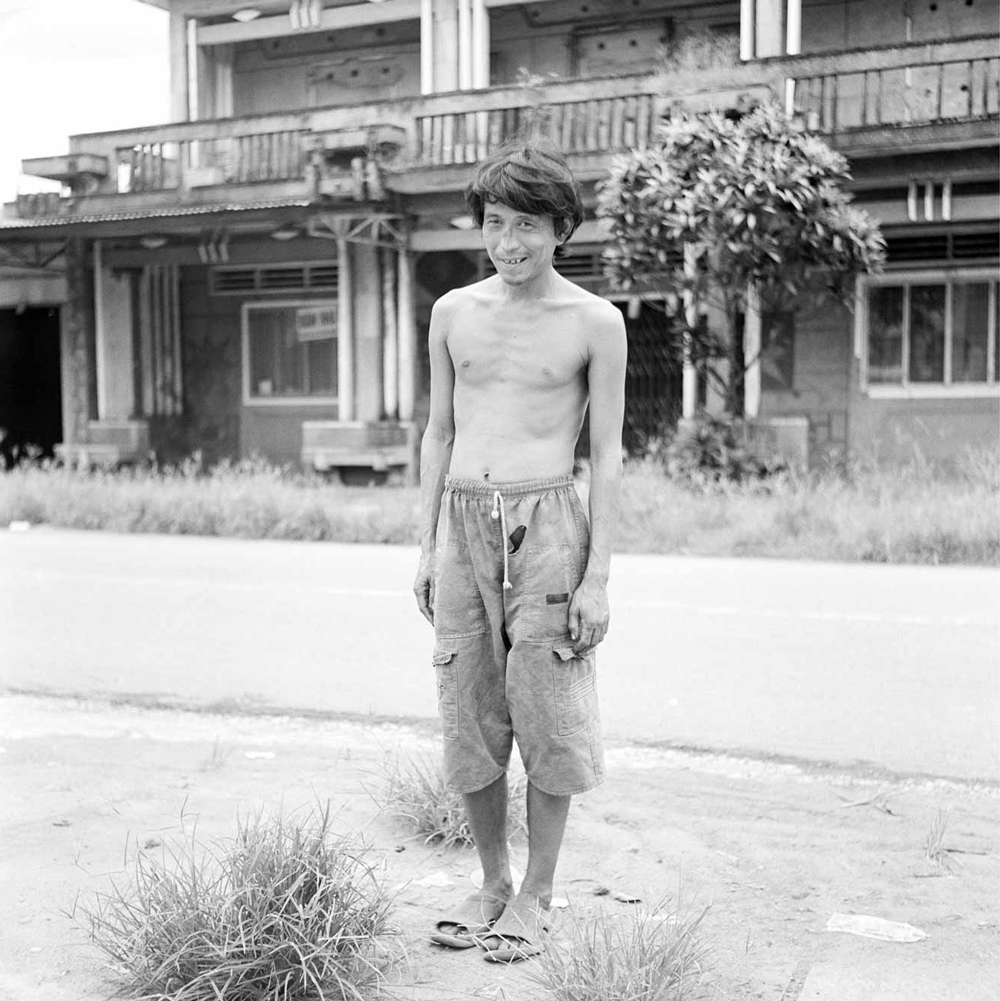

The artists also discuss their responses to this pattern of chronic under-compensation, with the most typical being supporting their lives and practices with more stably remunerated lines of work. Like the starving artist, the artist with a second job cuts a similarly recognisable figure—several of the interviewees share their own experiences of working additional jobs to support their practices, including restaurant work, sales, teaching, and street portraiture. As Gaëlle Choisne puts it, “I had a thousand positions, a thousand employments.”

While such approaches might serve to keep body and soul together, the artists also reveal how such working arrangements still have a negative effect on their practices—the most obvious being that time spent working another job is time not spent producing art and furthering their practices. In the event that multiple jobs net an artist a marginal existence, the pressure of meeting their basic needs compounds that effect. After all, when facing constant uncertainty in putting food on the table, paying rent, weathering medical expenses and other unexpected emergencies, how much energy can be mustered for creative effort?

Taken as a whole, this tendency towards under-compensation suggests an underlying, commonly-held belief on a much broader scale—a fundamental resistance to the idea of the artist as a worker whose time and labour should be fairly remunerated. Artistic work, it seems, isn’t quite thought of as properly real, and should thus be compensated more symbolically than materially.

Another stereotype exists to push back against the idea that there might be a problem at all: if artists aren’t being paid well enough to get by, why, they must be a pack of starry-eyed layabouts, who could be fairly paid—if only they worked hard and well enough to warrant such. Ang, in the film’s narration, rebuts this, noting, “If this is true, the museums, galleries, auction houses, and all other cultural establishments that are showing art, and profiting from it, should be empty. Instead, we continue to see astronomical sums of money being paid for paintings, more and more public and private museums, each one more lavish than the other. So to say there’s no money in art is simply not true.”

Vast sums of money flow on account of art, and precious little of it trickles down to the majority of artists. This accounts for how artistic life is made precarious, but does not quite answer the why of it. On one level, the simplest explanation suffices: those who find the present state of affairs agreeable seek its perpetuation, and have resources and influence enough to do so.

"Vast sums of money flow on account of art, and precious little of it trickles down to the majority of artists. This accounts for how artistic life is made precarious, but does not quite answer the why of it."

Yet self-interest alone may not explain why artistic poverty continues to be romanticised. Behind the stock figure of the impoverished artist may lie a deeper underlying assumption: that poverty and suffering make for great art. They provide experiences for the artist to draw upon, while also serving a roundabout function as an artist’s bona fides, their artistic expression unclouded by greed and vanity: a strange, latter-day mutation of notions of sacred poverty.

Economic precarity, as the film attests, is anything but romantic for the people living it. As Ang remarks, “There's nothing romantic about not being able to afford a beer, a meal out with friends and a generally proper life. There's nothing constructive in not being able to afford a space to live and work or buy material. There's nothing charming, in fact there is a certain wretchedness that struggling, desperate artists wear that is off-putting to many.”

Although seemingly contradictory, the reality of economic precarity and its romanticisation also exists alongside an ever-increasing pressure for artists to perform, so to speak, as more successful, sought-after versions of themselves: adopting personae in an effort to call them into reality. Interminable shop-talk and self-marketing at exhibition openings has found space to grow through social media, further blurring the lines between these performed selves and their associated art practices.

Away from the public eye, there is another avenue for performance that takes up an increasing share of artists’ time: textual, administrative performance, for the benefit of those who hold the purse strings. Applications for various grants, residencies, and other such opportunities represent a significant potential time sink. Their language must be carefully crafted to address the concerns of an array of potential stakeholders, all with differing ideas about why giving an artist money could make sense—and at every turn, the notion of realising a return on investment is never far away.

As the film makes clear, there are deep flaws in the art world as presently constituted. One has to wonder how there even are artists, given the pitfalls of this line of work. In considering this question, I am reminded of a remark made by the character Mr Wednesday in Neil Gaiman’s novel, American Gods: “The finest line of poetry ever uttered in the history of this whole damn country was said by Canada Bill Jones in 1853, in Baton Rouge, while he was being robbed blind in a crooked game of faro. George Devol, who was, like Canada Bill, not a man who was averse to fleecing the odd sucker, drew Bill aside and asked him if he couldn't see that the game was crooked. And Canada Bill sighed, and shrugged his shoulders, and said, 'I know. But it's the only game in town.' And he went back to the game.”

Which is not to suggest a sense of fatalistic resignation. What comes across from the various conversations in Living for Art is the artists’ clear-eyed sense of how the deck is stacked, and their determination to push ahead, regardless. The game may be rigged, but that is not an unchangeable fact of the world. Through open discussion of how money flows in the art world, and how artistic work is compensated, there exists the prospect of tipping the scales in a more equitable direction.