Cultural Dictionary: Authenticity

Text by Billy Tang

Photography by Bruno Zhu

Text by Billy Tang

Photography by Bruno Zhu

Authenticity is a question frequently raised to immigrants by the dominant culture. It is often a strategy to interpolate the subject in question to issues of genuineness, originality, rightfulness, legitimacy, and validity, underlying the concern of representation on behalf of other voices. The term's antomyn is unreliability and inaccuracy. When its etymology is explored with irreverence, an unconstrained space potentially opens up such that the dogma and orthodoxy of cultural systems and languages can be upended and played with.

With names such as K-Town or Chinatown, a small enclave or neighbourhood typically can be found in most urban cities around the world, where the concentration of inhabitants hail from a different ethnic or cultural background to those in the surrounding areas. They are historic settlements constructed in the image and memory of places far away from their immediate locality. Amongst the more ubiquitous of these by far are those affiliated with the Chinese diaspora.

As early as the 16th century, Chinatowns began to spread as far as Nagasaki, Japan; Binondo in Manila, Philippines; Hoi An in central Vietnam; Jakarta, Indonesia, and even up to Calcutta, Mumbai, and Chennai in India. More advanced trading vessels and shipping lines led to a further increase in settlements dealing with goods from silk to cotton wool. Later with the euphoria driven by the Gold Rush in North America, the mass exploitation of human labour, and along with the coerced opening of free border movement initiated by the Treaty of Peking, these conditions together led to an unprecedented acceleration of immigration to the West. As a hub for new sources of labour, culture and immigration, the existence of these neighbourhoods has historically been met with a complex mixture of intrigue, fear and in certain eras, outright racism and exclusion.

In the modern age, these enclaves have adapted to become self-reliant entities with architectural features and designs that have evolved as a subterfuge to placate the fear of the outsider by enticing them with a friendlier image of exoticism. Beneath this façade lies another hidden interior world, one mirroring the civic structures of a larger metropolis by creating a parallel system of commerce, social services and food for the immigrant community. Through a bottom-up patchwork of ad-hoc supply chains and independent enterprises, these neighbourhoods have gradually found a way to flourish and survive by developing a niche area within their host city. As an elusive and unique intersection for low-priced goods and cheaper manufacturing, these enclaves thrive within a circulation of commodities, that exists outside of the mainstream global marketplace. A first port of call for different ethnic groups and tourists alike finding their place in a foreign land, these enclaves reflect a continuously changing landscape. Intimately connected to districts in the city featuring low-income housing, the composition of these enclaves remains under a constant flux driven by displacements and successive generations of immigration. Many of these self-organised neighbourhoods have come to embody a complicated frontline to the wider ebb and flow of global trade and the entanglement of cultures. In many cities, they offer a unique way of life that is currently facing an existential threat in the form of rampant real estate markets and the homogeny of cultural gentrification.

"When its etymology is explored with irreverence, an unconstrained space potentially opens up such that the dogma and orthodoxy of cultural systems and languages can be upended and played with."

My favourite of all the different enclaves around the world is the Quartier Asiatique (or Asian Quarter in English), an unexpected post-1970s by-product of an urbanism project in the 13th arrondissement in Paris. The quarter is dispersed across an elevated esplanade of concrete pagoda units and a Buddhist temple; an 80s style subterranean shopping mall; and restaurants with names such as SINORAMA located on adjacent avenues that together surround a complex of a dozen residential high-rise towers collectively known as Les Olympiades. It’s also home to the Laotian Chinese supermarket Tang Frères, originally a small shop-front that has grown into one of the largest wholesale suppliers of Asian food goods operating in Europe. My own trips to this quarter began with journeys at the request of my beloved grandmother. I was often forced to take regular trips into the shopping mall in search for the latest shrink-wrapped bootleg versions of Paris By Night—a direct-to-video stage for the Vietnamese diaspora in the form of a dramatic musical variety show. Founded by a former gas attendant in 1984, Paris By Night was first imagined as cabaret-style performance to raise the morale of exiles and refugees through an epic program of dance routines mixing pop music, folk songs, one-act sketches and plays lasting a total four hours or more. It has since risen far beyond its humble origins to connect with the wider diaspora around the world. Due to high demand, the elaborate production line and celebrity talent structure of Paris By Night has now outgrown its Quartier Asiatique headquarters in Paris and shifted a little closer towards Hollywood by moving to the affluent suburbs of Orange County in the US. “Everything behind Paris by Night is Hollywood,” says Nguyen Cao Ky Duyen, one of the show's MCs. “Only the singers are Vietnamese faces. But from the director, the lighting director, the union—these are professional guys. Some of our dancers, they’re right now dancing with Beyoncé; they’re on tour with Britney Spears—they’re the best.”1

Rather than the common golden gates in other cities that usually demarcate a Chinatown economy structured more towards tourism, the centrepiece to Quartier Asiatique is a complex of structures called the Pagode. Imagine if I.M. Pei was convinced to “Pei-Plan” a collaboration with Robert Venturi, this unsung architectural landmark could very well offer a case study of what a revamped Chinatown of the future might look like. The Pagode stands in the middle of the giant esplanade with a skyline flanked by overbearing towers from all sides. Every time I visit, I’m struck by how marginalised realities become amplified by the structure, a late-80s-congregation of low-slung human-scaled multicultural buildings, standing in perfect contrast to the impassive brutalist surroundings of the Les Olympiades urban plan. Minimalist in execution, the rooftops pay homage to the hybrid facades of earlier Chinatowns, an approach that curiously mirrors the Chinese-Baroque style institutional buildings constructed in Post-Reform China during the same period.

Whenever I go to a new restaurant in an unfamiliar area, I always feel more at home when the menus are laminated in plastic with items such as prawn toast, chop suey or sweet and sour pork. Maybe it’s because of the consistency to the flavour that you can find no matter where you are. I have always been deeply fascinated with the ability of this under-appreciated food genre to mutate through sheer resilience, and its stubborn adaptability to any given environment. I’m interested in the jumps that happen when a food’s concept enters into another set of conditions far beyond its geography of origin. Whilst somehow maintaining a semblance of its previous life, methods of combining the dish with local ingredients evolves it to a point where it is no longer foreign but a unique dish in its own right.

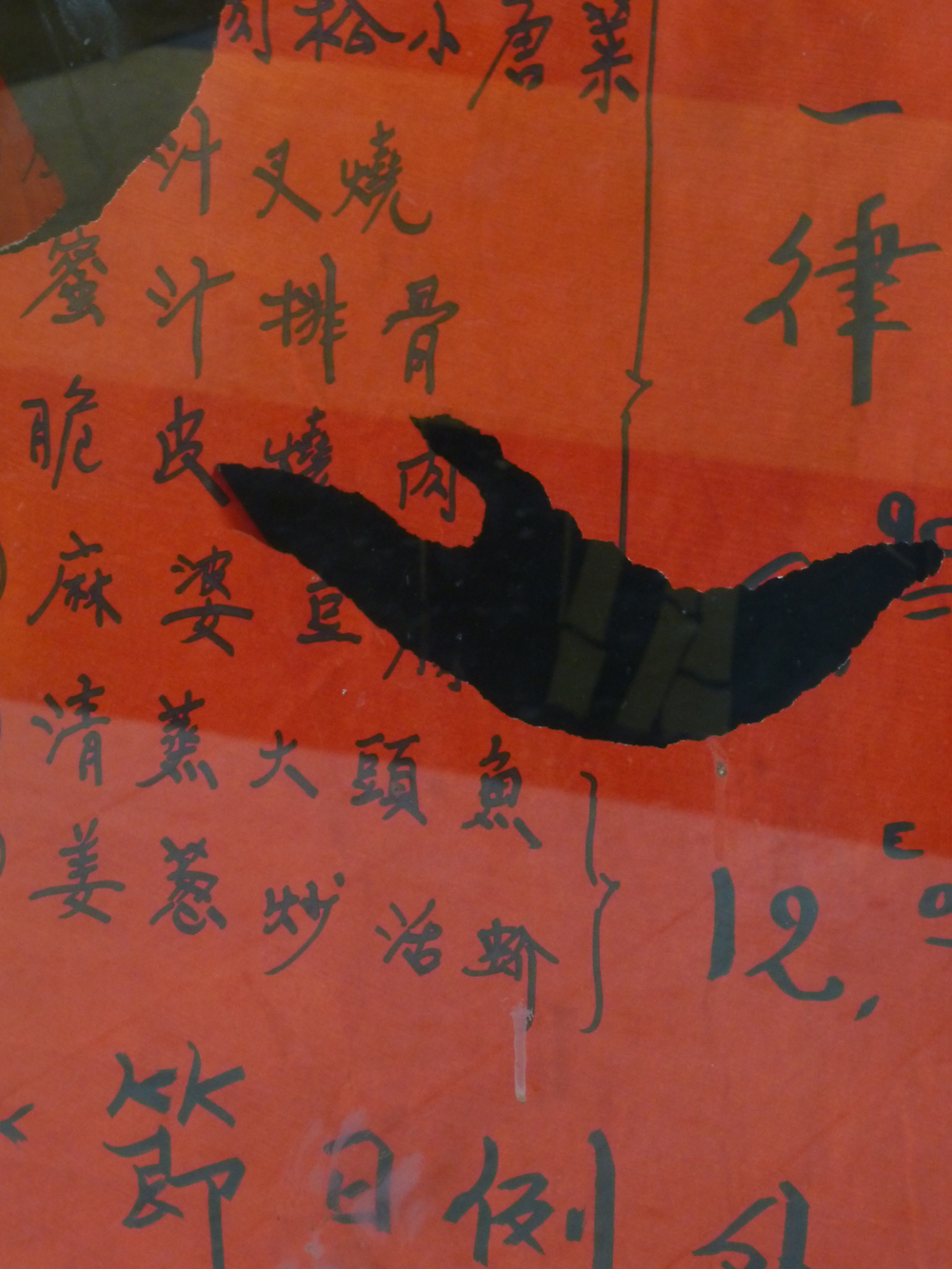

This kind of exoticisation and jump can conjure some very interesting food-related problems that are particularly palpable in French-Chinese bistros. A common device found in Chinese culinary ventures in France features mounds of food displayed in formation within a refrigerated window cabinet that faces outwards onto the street. It is a ready-to-warm genre that caters to a particular Western-inclined clientele. Here, inauthenticity is a melancholic and anonymous style of cooking in favour of survival first and foremost. The food display reflects a pre-packaged projection to the viewer of the food they want to have, like a safe and contained food court style experience, which happens from a controlled distance and transaction between cultures. It appeals to the prospective customer and gives them the luxury of being able to pick and choose, to check the quality in advance, while at a selected distance and according to their unique culinary habits. I imagine that this display method has its roots in the local patisserie or confectionary store. A typical pattern would be options such as siu mai [pork dumplings], har gow [shrimp dumplings] and a mound of hardened noodles and spring rolls. With the prolonged refrigeration, this carb-heavy mixture of meat and starch starts to coagulate in a specific way not so dissimilar to the Japanese art of samparu—the phenomena of compositions made from plastic replica food, which are displayed to look appetising, whilst increasing revenue for the shopfront it occupies. It’s an interesting evolution on the structure of cooking in relation to its display system. But what if the tables could be turned on this kind of setting so that the personality of the anonymous cook is a little more visible to the passing audience or customers?

Imagine if at the Quartier Asiatique there is a spin-off to this kind of display. Where instead of something pre-packaged, there is place to give home to a scattering of “food memories” representing an Asian kid growing up in the suburbs somewhere. Some savoury tapioca balls stuffed with minced meat, green bean and pork fat, then rolled with a coating of sticky white rice. Or a hybrid between lo bak go [turnip cake] and a thick slice of steamed rice noodle, something you normally only get in the old Chinatown district in Haiphong or through a friend of a friend living in an ethnoburb in the West (the suburban version of a Chinatown), where crispy scallions, minced pork and dried shrimp are sprinkled, ready for nước chấm [a Vietnamese fish sauce] to be poured on top before being eaten upstairs in this place, maybe they are steaming fresh phở noodles, made to capture the flavour of the soup better, whilst retaining a special amount of chewiness when you take a bite. Downstairs is where the broth is made—serving a type that uses rendered chicken fat as a base note to a beef broth infused with the freshness of spring onions (and sandworms roasted over charcoal for extra flavour). The decor would be spartan. There are foldable chairs and compartmentalised table arrangements for small group. Festoon lights are hanging off the ceiling and flickering to the background of live karaoke music. A side dish appears to be sweet potato fritters, deep-fried in turmeric batter with a fresh whole prawn embedded in it, then topped with shallots and finely cut cilantro. Papaya cut into thin transparent noodles, slowly absorbing the sweet fish sauce at the bottom of the dish, and sprinkled with roasted peanuts and slices of salted cured beef. There could be a series of random side-order options: a special sausage roll that sits there like a kind of red herring that nobody ever orders. For dessert, there’s light tofu served in a style of sugary eggnog on a pile of shaved ice and some red bean served in a cool transparent glass.

**

This article is part of Cultural Dictionary, a series in which guest contributors delve into cultural nuances to form a lexicon which may aid us in understanding the similarities and differences between us.

Billy Tang is a senior curator at Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai.