/frag-men-tā-SH(ə)n/

Noun

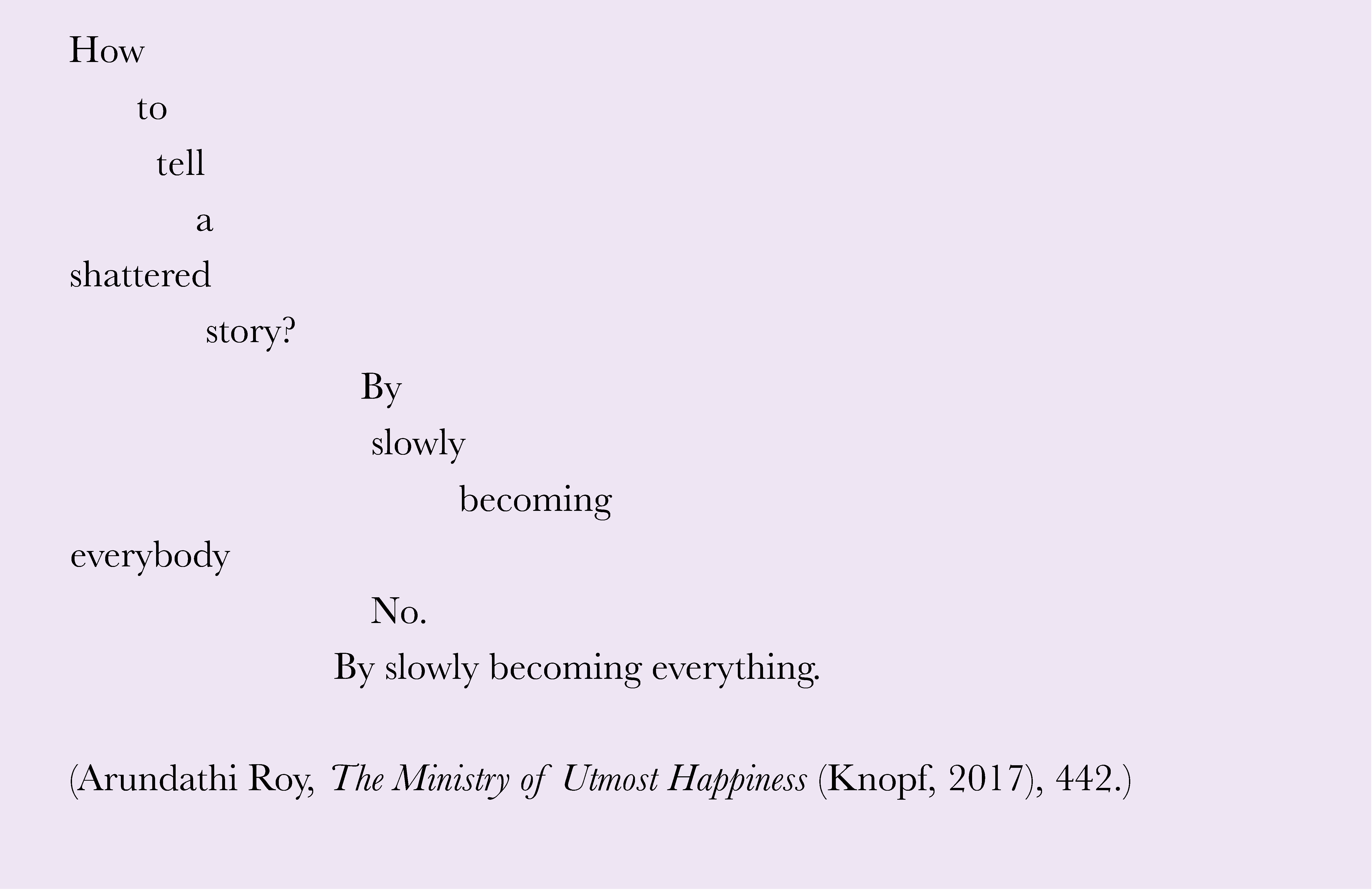

Fragmentation is a condition of being two or more. A wholly bodily state with nodes connecting in and across tangible and intangible things, time and geographies. Fragmentation as a continuous state of being might affect the stability of identity and rootedness, generating a loose feeling of homelessness and ennui.

After six months of living in New York, I take a sustained glance, a look back:

- 1. The body is always active in the process of staying alive.

- 2. Before winter. Leg-shuttling toward 23rd Street Station for the F train, I’m preoccupied with thoughts from an evening class. Near the shop selling supplements, C. asks, Have you started feeling homesick yet? I consider the question for a truthful response. No, I say, it doesn’t feel like I left Lagos yet. I miss family for sure. But homesickness? Too strong a word.

- 3. October. Not yet in the throes of winter. Somewhere in Brooklyn, I am waiting for the lights to cross over. A moped moves slowly along. Right after the light indicates “walk,” my legs cease to move. Overwhelming wistful waves invade my body; I realize I am reliving a moment from the past. Caught in a split, in a street in New York and transported back to the city of Lagos, to days of riding Okadas. A particular memory dilates: a rainy day, legs astride the back seat, body bobbing up and down due to the slippery bumpy road of Ondo street, heading back to my residence in Ebute Metta. I am at once here and there, in New York and Nigeria. The cold ejects me forcefully from this induced trance. I bend with my hands on my kneecaps to heave out a heavy breath. I walk.

- 4. Too lucid to deny, once at home, I realize I was wrong. I did miss home—it just came in parts. It will continue to come piece by piece.

- 5. Fragmentation here is framed through a psychogeographical lens; speaking to how the brain and heart is connected to geography. To look back means to not take for granted such a shift. To start, planting a question to dive deeper into the implication of movement: to move from here, what happens there? After? It is easy to underestimate the schism—a product of migrating from a familiar geography to a new one—since it isn’t a change marked visible on the body. It is different from travelling somewhere for a vacation, or any other sort of temporary encounter with a foreign land. It is indescribable too, that airy feeling you wake with in the first few months in a new land.

- 6. I lived near a mosque in Ketu. In my sleep, I hear the low thrum of the mosque’s call for evening prayers. A sound tied to the landscape dwelled in childhood. Blared from megaphones, uttered in Yoruba. Ọlọ́run Ọba ló tóbi jù lọ. Kò sí Ọlọ́run mìíràn àyàfi Ọlọ́run Ọba Allah. When I wake, I wonder why these sounds come to me. They didn’t haunt me when I moved from Ketu to Ikorodu, another residential location in Lagos. But now here, many land and sea miles from home, I hear soundscapes. Sometimes I walk in the street and hear my name in a crowd, the name only my father calls me by.

- 7. My body is mourning this distance by fragmenting. Reaching back to twelve year old me, pulling signification from three years ago, sifting a once-felt feeling through the sieve of memory. But this comes as a direct result of doing New York daily. The body I once knew is sawed at many points, with the influx of foreign occurrences—newer pathways, a new geometric orientation, more train rides than BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) rides, not-as-spicy soups, hard bread unlike the Agege bread I’m used to. All these new encounters demand space on the landscape that is my body. To accept there, I am unexpectedly breaking into bits.

- 8. January 2020. Deep in the recess of winter. It is the end of the day’s task. I am with C. again, talking about food as we head to Vanessa’s Dumplings in Williamsburg for a late lunch. We list weird animals we have eaten when on my tongue, the taste of Konko tries to relive itself. I let out a short grunt of frustration. Assuring C. I’m alright, I attempt to translate silently in my head what this one intense wave, like many others since leaving Nigeria brought. It is not so much that I miss the food, no. Konko is sour frog, smoked and prepared in Okra soup. The exact taste my body was scrambling to remember is the only kind of sourness you get from the special way it is fermented in my hometown in Ado-Ekiti. I didn’t eat this dish often, so I know this wave is not mere nostalgia.

- 9. My body reaches for fundamental memories and connection to a sense of self that was more whole and undisturbed, rooted in familiar grounds for more than two decades. It reaches deeper, as though it is trying to find the seed of myself. It wants to reconstitute a less discordant version of my geography in even seemingly irrational ways.

- 10. Homesickness used to be a condition so intense telling signs would appear on the body and could only be cured by sending the sick person back home to recuperate. On the surface, my dislocation is mediated by a permeable membrane that assimilates the new experiences to ease this friction as time goes on. Human beings have learned to evolve in face of unfamiliar circumstances.

- 11. But underneath all that adaptation that is ongoing, the act of looking back and taking a peek is to see the actual reality of how the body is staying alive: opening up again and again, a continuous fragmentation to open small vacuums for newer contacts with other cultures and newer forms of being.

**

This article is part of Cultural Dictionary, a series in which guest contributors delve into cultural nuances to form a lexicon which may aid us in understanding the similarities and differences between us.