On 12 February 2018, the official portraits of outgoing President and First Lady Barack and Michelle Obama were unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery, a part of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. In spite of the routine yet ceremonial affair of commissioning an artist to enshrine one’s likeness onto the walls of the nation’s history, the couple broke tradition not just by being the first African-American presidential couple, but also in their choice of black artists, Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald respectively, to paint their portraits. Known for their distinctive approaches to painting portraits of black subjects, their commitment to correcting an extended erasure of black people in Western Art was well suited for the task.

In an almost prophetic remark at the unveiling, Mrs Obama remarked “I’m also thinking about all the young people—particularly girls and girls of colour—who in years ahead will come to this place and they will look up and they will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this great American institution”.

Barely a month later, on 6 March 2018, an image of Parker Curry, a two-year-old black girl, mesmerised by the portrait of Mrs Obama at the National Portrait Gallery went viral. In an interview with the Washington Post, Ms Curry, Parker’s mother, said that Parker thought Mrs Obama was a real-life queen. In instances like this, we are reminded of the importance of representation in culture and politics alike, with its capacity to intimate potentialities through association and identification.

In many ways, it is Obama’s groundbreaking election victory in 2008 that offered the golden opportunity for introspection within the community. Indeed, it suggested that the prohibitions against black success were not insurmountable, shifting the community towards a greater embrace of its culture. It was this shift in the zeitgeist that empowered the Black Lives Matter movement; it was this shift that made the flagrant embrace of blackness by artists such as Beyoncé and Donald Glover so in sync with the pulse of the culture; and it was this shift that made Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer Prize victory possible. Yet, Obama’s eight years in office was anything but a victory lap; taking stock of progress also meant recognising that there was a long way to go. From residual confederacy to police brutality, the African-American community was burdened with the need to wrestle with the pushback against progress, ruminating over the continued vulnerability and fragility of the black body 150 years after the abolition of slavery. (Ironically, it made little progress in the policy space.)

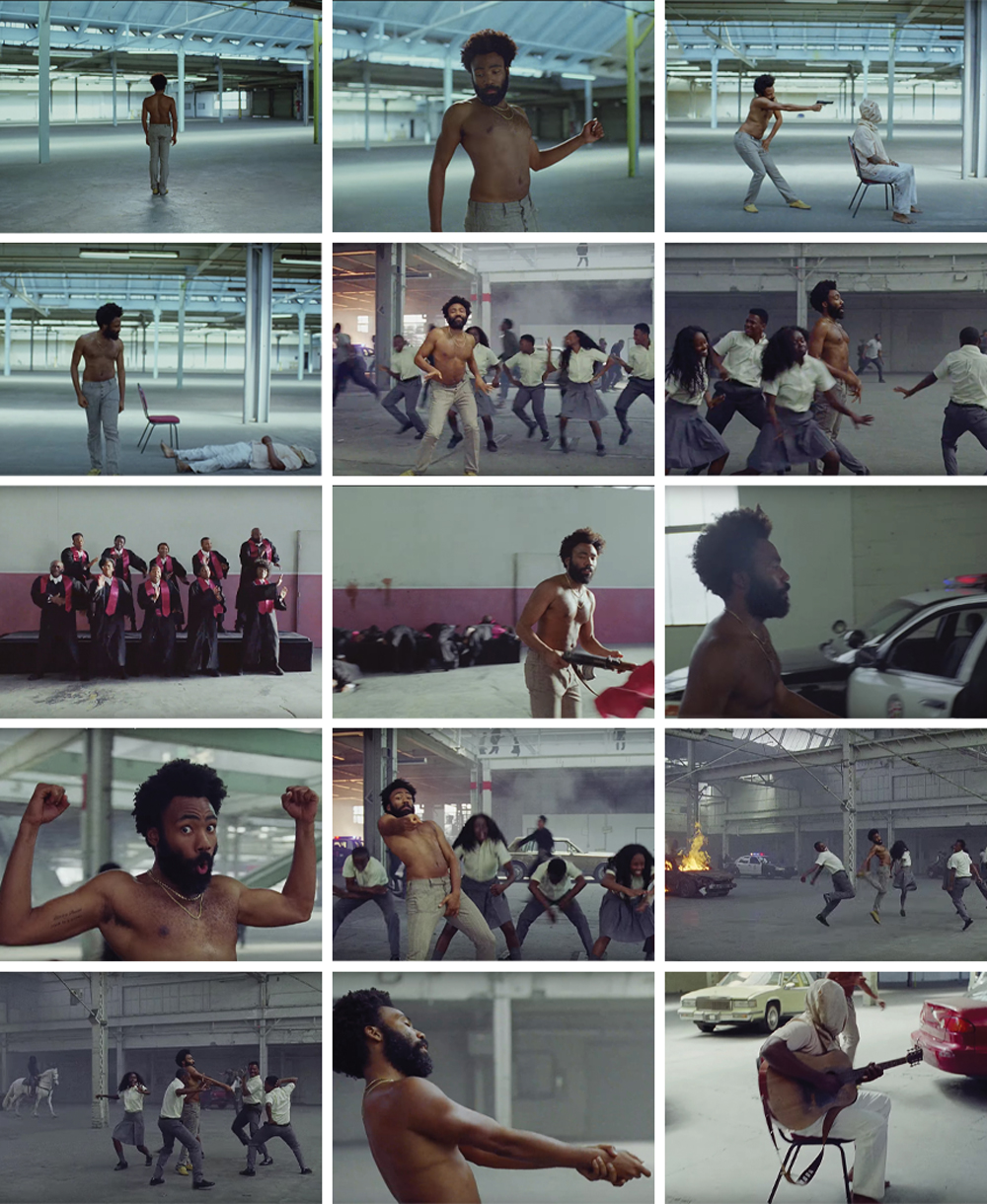

As a result of the growing prominence of the conversation, pop culture figures have waded into the fray, offering commentary in the best way they know—through their craft. In a recent music video for This Is America, rapper Childish Gambino (aka Donald Glover) presented 4 minutes worth of chaos jam-packed with historical references and loaded with cultural significance, barely giving the viewer enough time to catch a breath between episodes of carnage that unfold as Glover ironically and wryly dances in the foreground. Rhythmic oscillations between music and murder seem to metaphorically reflect the realities of being black in America, to live life at a suffocating pace that leaves moments of dizzying joy always susceptible to destruction and devastation. From Glover assuming the Jim Crow pose to his gunning down of a church choir (reminiscent of the Charleston church shooting by a white supremacist), Glover’s criticisms of racism in America are apparent. However, a deeper reading into the video offers a more nuanced understanding of the woes of being black in America. Instead of having a white person murdering black people in the background, Glover conducts the killings himself—intimating the notion that blackness is often complicit in the lethal violence that plagues the community, even as it bristles in resistance against the violence they are subjected to by whiteness. This recalls the ironic refrain repeated at the start of each verse in Kendrick Lamar’s The Blacker the Berry, in which he raps, “I’m the biggest hyprocrite in 2015,” with anger seething in the cracks of his voice. While listeners are left clueless as to why he makes such a claim, they find the answer as the song bleeds into its uncomfortable coda, in which Lamar growls with greater intensity, “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the streets, when gang banging make me kill a n*gga blacker than me! Hypocrite!” The reflexivity and intensity of both Glover and Lamar have been met by awe, shock and rapturous praise—reminding us that black artists have had enormous influence in pop culture through their acts of resistance.

Nowhere is this influence more saliently felt than with Beyoncé. In 2016, prior to the

surprise drop of Lemonade, Beyoncé released the music video for its lead single, Formation, where she explores a complex range of ideas from black pride to police

brutality. The track opens with a sample of late New Orleans rapper Messy Mya

asking “What happened after New Orleans?”, referencing Hurricane Katrina and the

subsequent neglect of New Orleans in its aftermath. As a city rich in Creole culture

and steeped in black history, this neglect was widely criticised as indicative of the

dispiriting disregard that white America had for its black counterparts. In stark

contrast to the lamentable treatment of blacks in America, she proclaims in the song

“I like my baby hair, with baby hair and afros / I like my negro nose with Jackson Five

nostrils,” recasting physical attributes commonly used to dehumanise black people

as primal features of beauty. In the video, Beyoncé straddles the top of a police car

as it slowly submerges into the New Orleans water. Nearing the end of the video,

police officers togged in riot gear are shown surrendering to a dancing black child in

a hoodie (archetypes used to label black men as wayward and dangerous) as the

camera pans to graffiti on a wall: ‘Stop Shooting Us’. The imagery is as laconic and

powerful as it is eerie and painful for the black people of America, who grow up

knowing too well the fears of losing their lives at the hands of those who vow to

protect them.

The video marked a shift in Beyoncé’s artistry to unabashedly embrace her blackness as her music took on a socially conscious approach while thumbing her nose at respectability politics. In place of saccharine love ballads and catchy club bangers, Beyoncé began to embrace the album as an art form, carefully curating each visual and song to contribute to a grander overarching message. At her recent performance at Coachella, Beyoncé opted for a bold, politically potent, historically resonant set that, among others, included the southern brass twang of New Orleans and Beyoncé herself singing the Black National Anthem. Of particular importance, though rarely discussed, is her choice of opening the performance clad as Cleopatra, the Queen and ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. As part of continental Africa, Egypt has had its own share of colourism, evident in the unending debate of whether Cleopatra was black. By dressing as Cleopatra, Beyoncé opened a performance that celebrated the diversity of blackness and forcefully reclaimed the association of blackness with royalty. On a meta level, her full-throated exclamation of black pride at a music festival primarily targeted at an audience of white majority was an expression of her refusal to distance herself from her culture regardless of her status and popularity.

Fast forward to 2018, Beyoncé releases yet another surprise album, this time in collaboration with Jay-Z, marked by the simultaneous drop of the music video for APESHIT. Apart from the excitement over a joint album by reigning hip hop royalty, the occasion was made notable by the fact that the video for APESHIT was filmed entirely in the Louvre. While many lauded the couple for taking over a (primarily white) cultural institution and filling it with blackness, the significance of the album far exceeds such simplistic tropes. As Doreen St. Felix of The New Yorker quite aptly points out, it is more importantly about “ordain[ing] a new status quo” in which “the Carters are their own protagonists in a grand narrative of establishing a black elite.” In a sense, the Carters have presented an unabashed blackness not simply based on embracing the traits that are commonly ridiculed by their white counterparts, but in presenting a new normal that naysayers cannot but accept. In Boss, off their latest album, Beyoncé brags “My great-great grandchildren already rich. That’s a lot of brown children on your Forbes list,” taking black love and black excellence into new realms with generational wealth.

In an era where white supremacists comfortably quote phrases like “Make America Great Again” in their acts of barely-veiled racism, black people live in a precarious socio-political climate that threatens to roll back on progress. When innocent black men are shot down for no apparent reason other than the colour of their skin; when justice seems to be an elusive privilege reserved only for a fraction of American society; and when progress is but a mirage, it is easy to feel powerless as a person of colour living in America. Yet, as artists continue to expand their craft to deal with the horrific indignities and painful ironies of being black, they do not simply offer salves for those within their community and offer a glimpse of what is possible, but also provoke introspection long held back by the asymmetry of white privilege.