Err'thang Gucci

by Lionel Ong

Err'thang Gucci

by Lionel Ong

The answer to the titular question, taken from Jay-Z and Kanye West’s “N*gg*s in Paris”, would have elicited very different answers pre and post 2015. Following Frida Giannini’s rancorous dismissal from Gucci, the design house radically overhauled the Fall 2015 Menswear collection that she had been working on, from the clothes right down to the model castings, intimating that the change was not going to be mere window-dressing. Known for her penchant for refined luxury and Italian tailoring, Giannini’s collection was thrown out the window, and along with it, the design aesthetic that she had so fruitlessly cultivated the past eight years. The fashion house’s back room design team, under the stewardship of then-obscure Alessandro Michele, worked tirelessly to recast Gucci’s languid image, sending male models togged in slinky chiffon blouses and lace tops in delicate hues down the the runway. It wasn’t so much androgynous as gender bending, taking traditionally effeminate silhouettes and fabrics, and fitting them onto male models, challenging our sartorial heteronormativity and blurring fashion’s gender divides with a saccharine flair.

Michele’s bold and progressive design aesthetic stood in loud and jarring incongruity with Gucci’s status as hip-hop’s favourite brand. This, is not merely a casual, throwaway honorific bestowed upon the Florentine fashion house, but rather, one that has been well documented throughout hip hop’s storied history. In 2015, Macy’s newly launched site M published statistics showing “10 Most Mentioned Brands In Hip Hop” between 1995 and 2015, of which Gucci effortlessly emerged first by over 200 tracks. Considering the hip hop, and by extension, the African-American community’s rampant sexism and homophobia, it seems odd that hip hop has remained curiously attached to Gucci as their go-to brand. In some sense, Gucci has arguably wheedled its way into the DNA of hip hop fashion, conferring Michele the privileged but precarious position of not just reconstructing Gucci’s brand identity, but also unwittingly pushing the boundaries of the way conventional black masculinity is perceived and constructed.

"You could be a gangster with a dress, you could be a gangster with baggy pants. I feel like there’s no such thing as gender."Young Thug (2016)

Hip hop music, with its heavy beats, groovy riffs and witty lyricism, has often been a window into the social, cultural, and political landscape of the black community. Through the lens of deliberately constructed narratives and truthful recounts of personal history, hip hop documents the culture of urban working-class African-Americans with richness, vividness, and generosity. Hip hop fashion and street style became a prism through which black people reflected their way of life and their aspirations, binding together their desires, ambitions, and feelings of self-worth to an array of clothing.

The induction of Gucci into street vernacular came in the late ‘70s all through the

‘80s, with the thriving bootleg culture that flourished in the streets of Harlem,

Brooklyn, and Queens. Luxury brands were a reflection of aspiration and the desire

to live well. Former Vogue editor Andre Leon Talley, explained that the “urban young

people are always addicted to fashion... because it is an expression of aspiration.” In

the mid ‘80s, a Harlem dandy by the name of Dapper Dan lent this sartorial

aspiration a materiality by opening his store on 125th street, with offerings such as

leather coats trimmed with the Gucci monogram, the iconic New Balance 572 given

the Gucci monogram treatment, as well as bootleg Gucci T-shirts featuring a logo

design appropriated from old packagings. Dapper Dan understood the aspirational

quality of luxury brands, taking their most recognisable asset—their logos—and

translated them into the accessible design language and affordable price tags of

streetwear. By capitalising on the logo mania of the ‘80s, Dapper Dan festooned

track suits cut in oversized masculine silhouettes with recognisable logos of luxury

brands such as Louis Vuitton, Fendi, and Gucci, creating clothes for an entire

generation of African-Americans who wanted to be dressed in the “freshest” clothing.

As such, when rappers like Kanye West spit verses such as “What’s Gucci my N*gg*?” over high-pitched synth riffs, or when Young Thug (in an ode to his aptly named mentor Gucci Mane) confidently proclaims “Everything Gucci, bitch I’m good” over forceful trap beats, they are drawing from a tradition that saw the acquisition of “fresh” clothes as a hallmark of living well—a widely understood representation of status and a decisive expression that “I’m good”. It is also a clever play on the sound of both words, emphasising the drawn out first syllable; morphing the statement into an accentuation of wealth and wellbeing.

In the 90s, hip hop’s obsession with fashion brands acquired a new, ostentatious character. During his stint at Uptown Records and later on at his own label Bad Boy Records, Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs revolutionised hip hop’s relationship with fashion. Not content with simply being dressed well, P. Diddy dressed his artists in gaudy luxury, embodying the fleshy excess that hip hop is associated with today. In Notorious BIG’s “Big Poppa”, Biggie raps about living “in mansions and Benz, giving ends to my friends” and brags about “living better now, Gucci sweater now”, his ego wafting upward on a bedecked cloud of luxuries. This lyrical trope of name-dropping brands employed by rappers to paint a gaudy narrative of their rags-to-riches story, remained largely intact throughout the noughties to this day. Brands like Gucci thus progressed from being a means to an end, to being an end in itself.

Cut to the year 2016, rapper Tyga released a track titled “Gucci Snakes” featuring

Desiigner. Over a bouncy bass and Desiigner’s auto-tuned ad-libs, Tyga raps about

spending “10 bands on Gucci”. Within the same week, famed hit-maker Jermaine

Dupri released a single track title “Alessandro Michele” featuring ’90s rap veteran,

Da Brat. The track opens to the oft-repeated refrain “Everything Gucci”, and the two

rappers trade bars over heavy Timabaland-produced beats, bragging about their

success with excessive aplomb. Dupri even makes reference to Gucci’s signature

ribbon, "red and green, you know with the white stripes”.

This continued name-dropping would not be so curious if rappers employed Gucci

merely as a symbol of luxury or as a nod to street colloquialism. Yet, this attachment

to Gucci has expressed itself beyond the domain of lyrical content, finessing its way

into the wardrobe of some rappers. While less adventurous rappers like Tyga have

been seen sporting leather Gucci bombers and denim jeans with literal “Gucci

Snakes” snaking down the fabric, Kanye West and 2 Chainz have embraced Gucci’s

more delicate offerings, wearing the now ubiquitous denim shearling jacket that is

intricately embellished with floral and fauna embroideries. In Vanity Fair’s March

2016 issue, rapper ASAP Rocky was pictured reclined on a chaise longue, dipped in

Gucci from head to toe, with a peachy floral silk robe and a pair of olive embroidered

trousers. Similarly, on Young Thug’s cover of Dazed & Confused, Hip hop’s most

outlandish iconoclast was clad in a red Molly Goddard tutu and a matching floral

Gucci laced cropped top, subverting the stereotypical hyper-masculine image of

rappers.

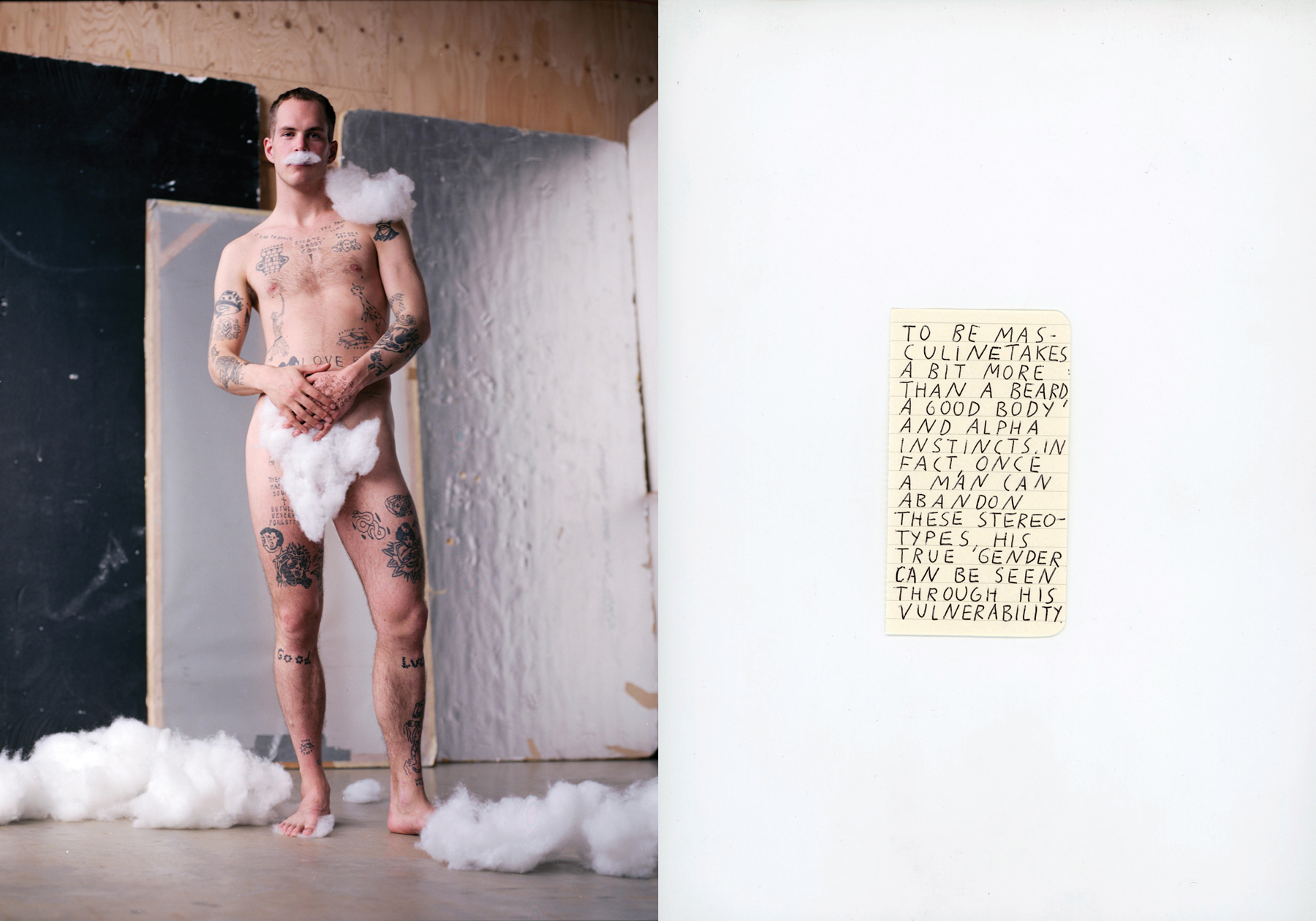

By contextualising hip hop as an extension of black culture, hip hop places an

emphasis on hyper-masculinity which extends from the experience of a black male.

Male performers and artistes understand that an essential brusqueness has become

an important aspect of their performance. Traditionally, this “hardness” manifests

itself in stereotypical heavy chains, oversized hoodies and bold tattoos, as rappers

rap about the struggles of the streets, getting money and the life of a true “G”

(gangster). This is where artistes like Young Thug buck the trend. In his Calvin Klein

Fall/Winter 2016 campaign, Thugger explains why he has no qualms wearing

dresses and expounds on his perception of gender, saying that “You could be a

gangster with a dress, you could be a gangster with baggy pants. I feel like

there’s no such thing as gender.”

By rejecting gendered notions of clothing, Thugger unwittingly echoes the sentiment

of renowned gender theorist, Judith Butler, who famously challenged the notion that

our biological sex engenders certain behaviours in relation to society. In her seminal

work, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution”, she propounded the notion of

“gender peformativity”, arguing that gender is not biologically determined, but a

socialised and mediated construct in which certain characteristics are “performed”

based on cultural expectations and social habituation.

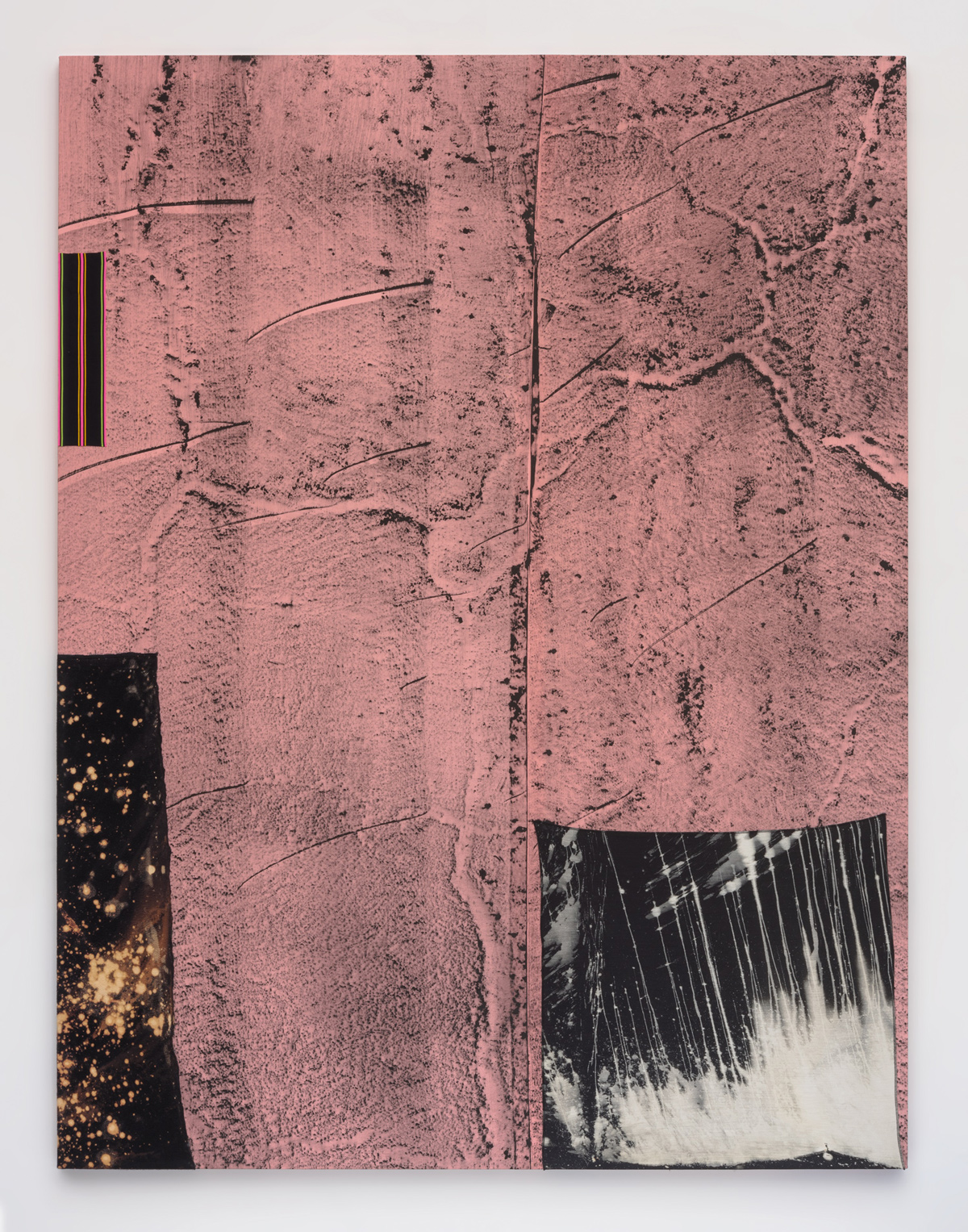

Whether donning a laced top or a flamboyant silk robe, these rappers are flirting with

the blurred lines of gendered attire and flouting the rules of what a black man should

look like, all while dressed in Gucci. When fighting against traditional notions of

dressing up, the array of gender-neutral clothing designed by Gucci’s Michele seems

to have become the choice armour for foppish rappers looking to subvert traditional

tropes of black masculinity. Since taking the reins of the iconic fashion house,

Michele has proven himself quite the iconoclast, radically reinventing Gucci’s design

aesthetic with soft and feminine floral prints, elaborately sensual lace, richly ornate

brocades and impeccably delicate embroidery; injecting a quirky, romantic quality

into the clothes while constructing an entirely different brand identity.

Beautifully embellished and luxuriously flamboyant, Michele’s clothes are

unintentionally pushing the boundaries of black masculinity, helping rappers

do away with antiquated gender binaries. While rappers like Young Thug have

been met with homophobic accusations (he is not gay) and incredulous mocking,

industry muses like Luke Sabbat and Ian Connor have applauded Young Thug’s

defiant style. Come 2017, when Gucci merges its menswear and ready-to-wear

runway shows, one can only hope that Michele will continue to put a strain on the

rigid conception of gendered clothing, and perhaps lure more rappers with the

brand’s enticing assortment of apparel.

As the reconsideration of black male identity is inextricably linked to the issues of

sexism and homophobia, the conversation on black masculinity remains fraught and

complex. Even while challenging sartorial norms, true progress cannot be made if

the tradition of misogyny and homophobia remain intact. While untangling these

knotty issues may take time, on the sartorial front, it is comforting to see rappers

armed in Michele’s Gucci challenging traditional tropes of black masculinity,

exemplifying RuPaul’s controversial aphorism—“We are all born naked and the rest

is drag.”

Photography by Stefan Gifthaler | Styling by Noey Park | Grooming by Sara Mencattelli | Model. William (Rockmen)