Last May, Minneapolis man George Floyd was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin, another senseless death in the long history of racialised police brutality that the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement resists. Despite lockdowns in the face of the worst pandemic in living memory, Floyd’s killing sparked what might have been the largest wave of protests in American history. The police response, livestreamed and shared on social media, could only further inflame tensions: beating unresisting protestors with animalistic fury, indiscriminately firing tear gas and rubber bullets, maiming many, ramming crowds with vehicles, and so on—a stark contrast to recent events in the United States Capitol, where a whiter, wealthier crowd of protestors was greeted with considerably less violence.

As the protests spread across the globe, addressing racial inequalities and injustices specific to particular cities and countries, others had been exploring another avenue for demanding redress of injustice: demanding accountability from major cultural institutions, ranging from museums, to art galleries and publishing houses.

Some of us in the worlds of art and culture have privilege enough not to delve into the histories of these august institutions, nor to have been subject to discriminatory, predatory practices that become open secrets, whispered about but never directly acknowledged. There are those of us comfortable enough to see them as somehow neutral, elevated above the ugly realities of the world. Yet the vast flows of wealth and influence which animate these institutions are becoming increasingly visible, wending back, in some cases, to horror and atrocity.

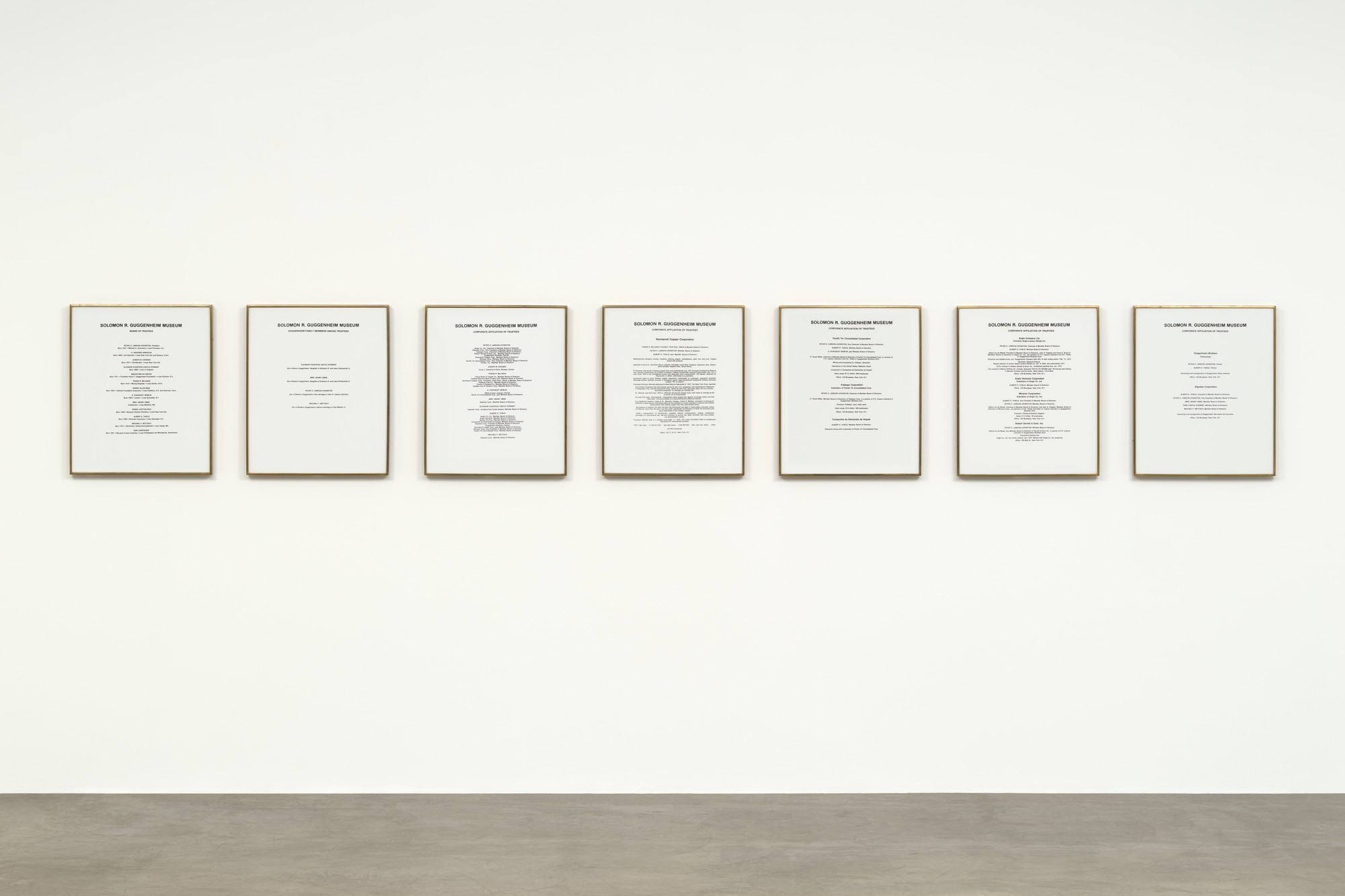

The Guggenheim fortune, for instance, finds its roots in colonial extraction—establishing tin mines in Bolivia, gold in the Yukon, mining diamonds and tapping rubber in what was then Emperor Leopold II’s notorious Congo Free State, diamonds in Angola, and copper in Alaska, Utah, and Chile. Unsavouriness is not merely confined to their distant past: Hans Haacke’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum board of trustees (1974) drily lays out how, when the democratically elected Chilean Congress unanimously voted to nationalise Kennecott Copper Corporation, the company responded with a campaign of economic strangulation, attempting to block copper exports on which the country relied. After a military coup in 1973, the new junta quickly moved to compensate Kennecott Copper Corporation for their losses; the work detailing how one of the museum’s supporters had benefitted from violence.

Yet mention of the Guggenheim name rarely evokes such sordid things, for in 1937, Solomon R. Guggenheim purchased for himself stately, Pharaonic immortality as a dignified patron of the arts through his eponymous foundation. Close examination of other foundations and endowments may well uncover similar tales; viler still when it comes to the grand museums of imperial powers past and present, their collections a testament to centuries of looting and subjugation. These fine, upstanding institutions stand amongst us as undying monuments, fuelled by blood and oppression.

What is to be done? There has been some cause to cheer, through the efforts of various activist and protest groups. Facing pressure over having a coloniser for their namesake, the Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art was recently renamed the Kunstinstituut Melly—a reference to Ken Lum’s permanent installation on the building’s facade, Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1990). In response to furor over their role in the American opioid crisis, a number of major museums elected to refuse donations from the Sackler family, with the Smithsonian and the Louvre also rebranding or renaming wings named for the family.

The head of Serpentine Gallery, Yana Peel, and the vice-chairman of the Whitney, Warren Kanders, were both pressured to resign, over their ties to an Israeli cyberweapons company and a manufacturer of tear gas and other law enforcement supplies, respectively. In response to the New York Academy of Arts’ handling of Maria Farmer’s accusations of the school having enabled her abuse by the late financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, student protests and mass resignation of trustees finally moved the school to issue a profound apology to Ms Farmer.

In a more positive vein, a series of recent, high-profile hires of Black personnel by major institutions suggest at least some attention being paid to both the long history and present ubiquity of racism in the United States: Naomi Beckwith being named deputy director and chief curator of the Guggenheim Museum, critic Antwaun Sargent joining Gagosian as director and curator, and dealer David Zwirner hiring Ebony L. Haynes to open and run a new exhibition program and commercial gallery space, with an all-Black staff.

Though these changes are undoubtedly positive, how much can such appointments, resignations, renamings, and redirections of money and influence change the course of these great hulks? Consider how, over the past year’s BLM protests, protesters cheered—and rightfully so—as they pulled down statues of confederate soldiers and other champions of colonial bloodthirst.

Despite this, in terms of concrete gains, there was little to be had: at the state and municipal level, prettily-phrased announcements ran cover for largely toothless police policy reforms, with a scant handful of budget cuts (incredibly, Minneapolis approved more money for the police). Perhaps the most brazen display of empty performativity was New York City mayor Bill de Blasio having a BLM mural painted in front of Trump Tower, even as his touted budget cut for the New York City Police Department was revealed to be a compilation of accounting tricks that did not ultimately reduce the power of the department.

At the federal level, proposed legislation appears to be mired in the Senate. At the time of writing, Derek Chauvin and three other former officers await trial, having been released from custody after posting bail (to the tune of $1 million for Chauvin, and $750,000 each for the rest). The statues fell, but much remains the same.These recent changes at major cultural institutions are a step forward, but to take only a single step is to be eventually overcome by the centuries of momentum invested in these institutions. It is only through sustained effort that this implacable force can be challenged, even remade, to achieve lasting change.

The nature of such a change, and the tasks necessary to implement it remain complex questions. We have seen that pressure from below has already yielded results—in the near term, it seems natural to extend and organise that pressure, to find ways to yield greater transparency, to obtain fairer labour practices, following a general principle of always seeking both to reduce harm in the present, and to reckon with such harms that linger in the past.

As to our own context, we have our own particular histories (and present realities) of injustice to grapple with, to an almost fractal degree: critically observed at any scale, there are problematics aplenty to tease out, whether one zooms into the cultural sphere, or considers Singapore more generally—our own specific history of racial animus and dispossession through the upheavals of colonialism and after, say, or the structure of labour regulations and social safety nets as shaped by the relentless thirst for foreign investment.

The very least that can be done, regardless of our limitations on speech, assembly, and organisation, is to engage critically with all that surrounds us, asking (particularly of our institutions), amongst other questions: how does the money flow? Who gets hired or shown, and why? As with the recent townhall on the closure of The Substation, questioning minds are drawn together to confer and dispute, to discuss what can be done. Prescriptions of greater detail are perhaps beyond my own understanding and experience.

The scope of our work is daunting, to be sure. We have only the world we live in, wherein countless generations of victors have written the histories and built the institutions, sometimes atop piles of corpses. There is little else to do, but to try to set right what we can.