A disembodied stream of amber urine collects in a whiskey glass. Intestines, blood, and liver are deposited neatly into airport security trays. A head, decapitated, bounces improbably up a flight of stairs, spurting flecks of blood. These surreal, discomfiting images feature in the video works of British artist Ed Atkins (b. 1982), whose creations and performances have been exhibited in London’s Serpentine Galleries and New York’s New Museum. Video may have killed the radio star, but it certainly launched Atkins into art stardom. Produced by motion capturing devices along with computer generated imagery (CGI), Atkins’ works present disturbing virtual realities through the visceral nature of their content, as well as the high definition renderings of his characters. “Characters” might even be too humanising a word—Atkins has referred to them as “CG avatars”, speaking to his work’s purposeful dematerialisation of human presence onscreen. They are representational figures, but whom or what do they represent?

These avatars, like the reanimated corpses in zombie flicks, compel viewers to confront their impending mortality. Atkins tickles our subconscious awareness of death’s nearness by bringing our attention to the absolute emptiness—or ‘emptying-out-ness’—of modern technology. Cinematic representations of reality verge ever closer to hyperrealism, with Ang Lee’s recent Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk shot at an unprecedented 120 frames per second in 3D at 4K HD resolution. But audiences have been unimpressed: Daniel Engber, a writer for Slate Magazine, deemed the effect “unnatural and offputting” when mixed with narrative-driven cinematic grammar.

In works like Ribbons (2014) and Happy Birthday!! (2014), Atkins’ avatars—constructions of uncomfortable realness, every pore and wrinkle visible for our benefit—similarly inhabit the uncanny valley.

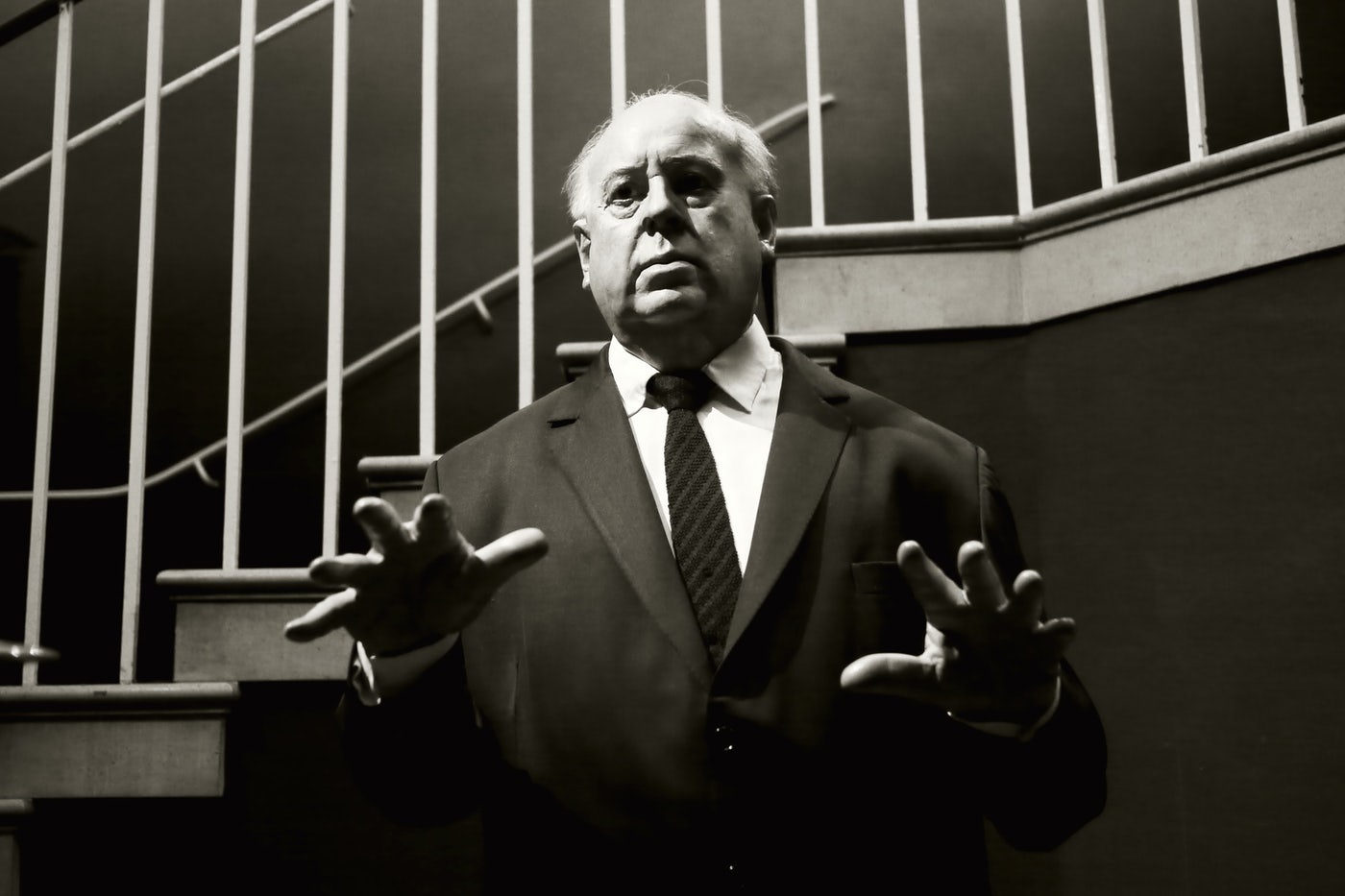

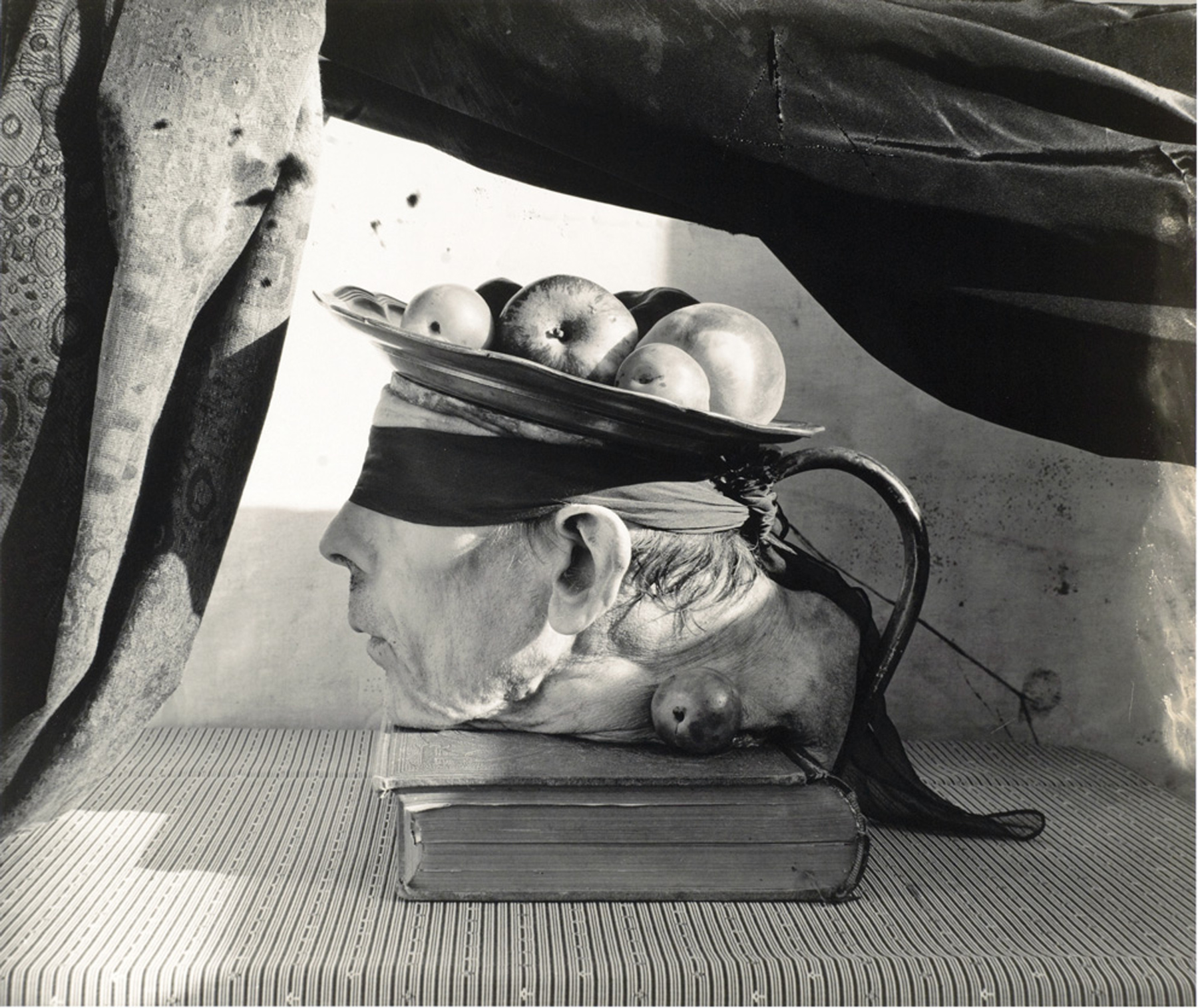

The avatar is always a realistic-looking, lean, white man; always handsome, in that unplaceable way, reminding one of this or that movie star. And yet, there forever remains something a little off, as this humanoid figure invariably rubs up against the obvious signs of his falsity. His mouth mimes the voiceover (provided by Atkins himself) with impeccable timing, but it is too stiff, too unmoving, and not just in that British way. The eyes and eyebrows, defined with unnerving precision, move in the simulation of facial expression, but the pupils are entirely still, and undeniably dead. Atkins’ more recent Performance Capture (2015–16), expands the subject of his work, or, rather, subsumes more subjects under one avatar. More than 200 performers read his original poetry aloud, allowing their movements, voices, and facial expressions to be captured and recorded. These distinct personalities flow into each other as they are expressed through a single avatar: a man’s torsoless head and arms. His voice, which is the voice of each performer, changes with every few lines, and his appearance changes also, ageing and deteriorating as the piece persists.

-still2.jpg)

-still1.jpg)

-still.jpg)

-jpg.jpg)

The sharply rendered materiality of these avatars—the utter detail with which their skin, teeth, and hair is designed—works in conjunction with the failure to capture any sense of true liveliness. This, along with the unintelligible and possibly meaningless soliloquys narrated by the avatars, signifies a total emptiness behind what Atkins has called a “deathly mortal image”. In Atkins’ installations, where his videos inhabit multiple huge screens in galleries and exhibition spaces, the “questionable corporeality” of the monstrous avatars is emphasised. They might fill the space, but they themselves are vacant: at the end of Ribbons, the avatar named “Dave” literally deflates like a balloon, his sunken head coming to rest on a bartop. This ending comes as a relief—no longer must we endure the disquieting, failed approximation of an inner life. Catharsis has been achieved. We leave the work, secure in our sense of complex interiority; aware of and grateful for our own bodies and their full-blooded flesh.

Yet, effective though they are at grappling with ideas of ageing, illness, and death, Atkins’ works also strike this viewer as potentially tone-deaf in an era where the news keeps us up to date on unending global strife. Every day we learn of regular airstrikes killing hundreds in Syria; of black people at constant risk of police brutality and murder in the United States. Being able to dread a slowly impending doom, then, is a privilege. It is a luxury. It is one that is unavailable to the many who have experienced, and continue to experience, the realities of swift and unexpected slaughter. Atkins creates fantasy worlds with hostile environments that force his white male avatars into self-mutilation, violence, and abjection, all in order to elucidate the apparently universal theme of mortality. But there are people who need not be reminded of their mortality by post-Internet video art, simply because they must already reckon daily with the precarity of their racialised and gendered lives. Atkins’ failure—or refusal—to engage with these issues reveals how white male anxieties around morbidity are fundamentally disconnected from the histories of the oppressed and colonised. White maleness has long subjected people of colour and trans people to terrifying and inhospitable conditions, and Atkins’ fantasy of a violenced avatar in his image does not do much to address that.

In his interviews, the artist has tried to acknowledge that gap. He notes that part of his approach comes from “being a white man approaching a certain obviation—boredom—with himself”, and has justified the perpetually white avatar as a deliberate commentary on who gets to be the face of “empowered, homogenised cultural normalcy”. Optimistically, one might suggest that Atkins ventriloquises white maleness as a cadaverous mask in an attempt to point out the artificial, self-perpetuating nature of whiteness as an identity. In Safe Conduct (2015), a white man rips off his face over and over, singing tunelessly to himself as he reveals, infinitely, the same blotchy visage underneath. Performance Capture destructively compounds multiple identities under the archetype of generic white maleness.

Perhaps, with their fraudulent corporeality and their strange facial tattoos reminiscent of neo-Nazis, the avatars may be read as the white artist performing whiteface. Atkins’ white men, emptied of humanity and presented as lifeless veneers, could stand as corrective analogues to a history of blackface, yellowface, brownface, and other modes of hateful racial performance that many parts of the world—including Singapore—have yet to properly scrutinise. If so, it is disappointing that these truly subversive aspects of his work have rarely been the focus of the art world’s esteem; they certainly did not seem to figure into Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist’s praise for him as “one of the great artists of our time”. Atkins’ interest in troubling the construction of whiteness appears to have been sidelined when it should be encouraged. You see, white mortality is boring. But apparently, the assassination of whiteness is still far too frightening for Atkins’ supporters to consider.