Of Beansprouts

& Braids

& Braids

Text by Grace Hong

Photography by Clifford Loh

Two braids, a shoe, a mirror, and a mountain of beansprouts—these images spring

to mind when one mentions Singapore-born artist Amanda Heng, objects signifiers of

the artist’s seminal performance pieces. Perhaps the QR code is now added to that

list. We spoke to the artist during the launch of We Are The World - These Are Our

Stories, a marked transition in her oeuvre. Born in 1951, Amanda Heng was a thirty-something income tax officer who quit to become an artist. After graduating from

Lasalle with a diploma in print-making, she started by using her body as the main

medium; a decision she reasoned as the body being the cheapest medium available.

This, coupled with her sensitive use of collaboration in her practice helped cement

Heng as one of Singapore’s foremost performance artist. She also helped to found

two art collectives—The Artists’ Village (1988) and Women in the Arts (WITA)

(1999), and was awarded the Cultural Medallion in recognition of her contributions.

One of Heng’s symbolic work is Let’s Walk (1999), a street performance series that

involves the artist and participants each holding a high-heeled shoe in their mouths

while walking backwards, with only handheld mirrors to guide their way. It was in part

a response to the 1997 Asian financial crisis which saw female employees being laid

off first and many Singaporean women spending on their appearances for job

security.

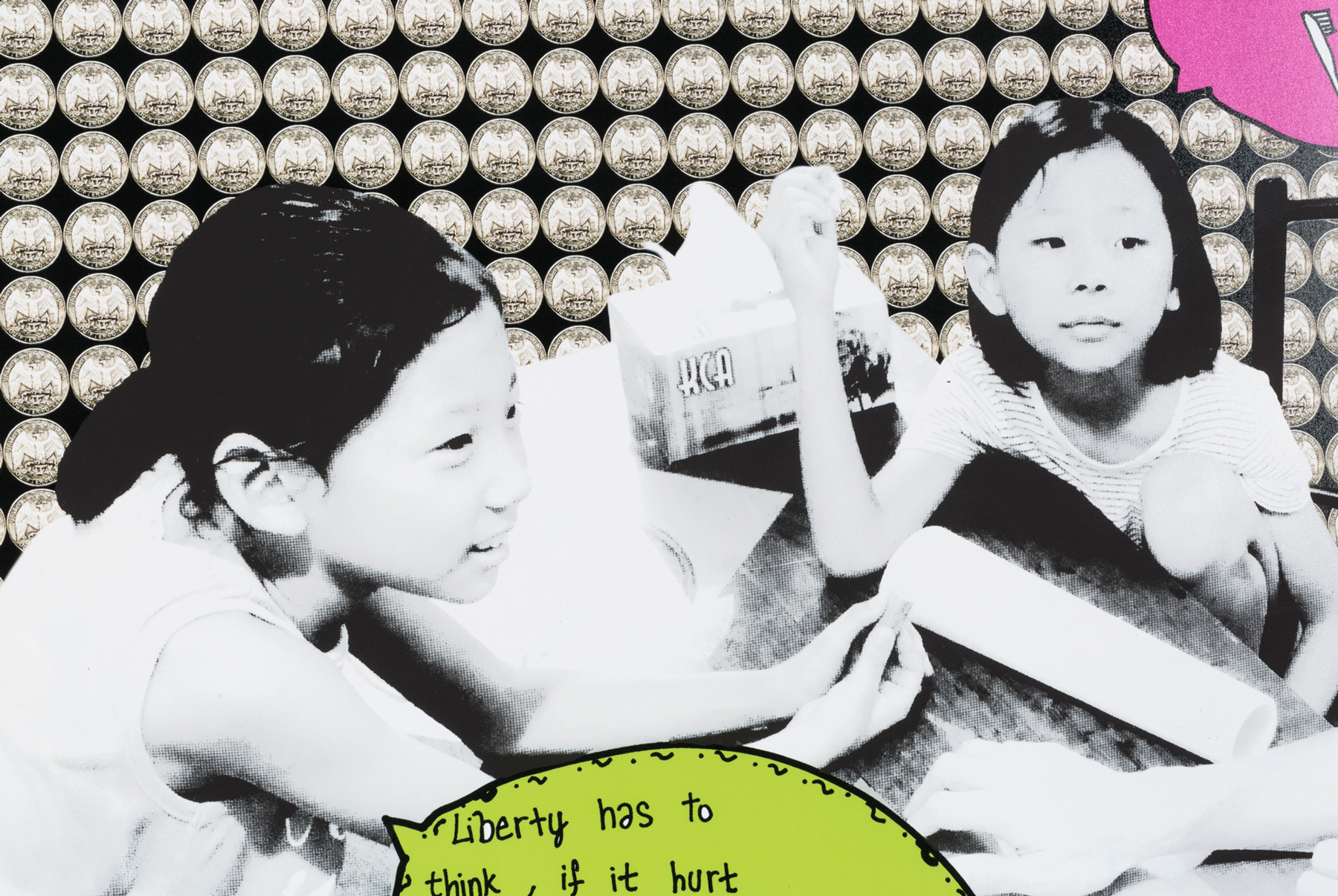

Incorporating everyday objects to convey a straightforward notion, Heng’s

performance pieces are accessible to the man on the street; a feature that renders

her works powerfully poignant. Another series, Singirl (2000 – present), saw Heng

donning the uniform of Singapore Airlines’ cabin crew—critiquing the branding and

marketing of female staff as “Singapore Girls” as well as the destruction of heritage

sites.

But having visitors interact with the life-sized cut-outs of the artist was only the first

level of participation. During Heng’s first solo exhibition in 2011, Singirl was

accompanied by a demarcated, private space resembling a toilet cubicle set up in

the Singapore Art Museum’s gallery. Female visitors above the age of eighteen

could take part in the online art project (still ongoing today) by having photographs of

their bare buttocks taken by the female gallery-sitter on duty and added to the

collection. Visiting her exhibition then, the prospect of hitching my skirt up and

mooning—albeit privately and anonymously—within a white cube institution, was

exciting. But more than that, I realised the efficacy of Heng’s many works laid not in

the artworks per se, but in the inclusivity endowed upon each work, a feature

perhaps unique to her practice. On her part, she consciously emphasises the

audience’s significance and creates a void for others to fill. In doing so, Heng draws

people in, individuals who cannot help but participate. Unlike most artworks which

primary needs lie in broadcasting a message to the world, she acts as a mouthpiece

for those she encounters, and for those who encounter her works.

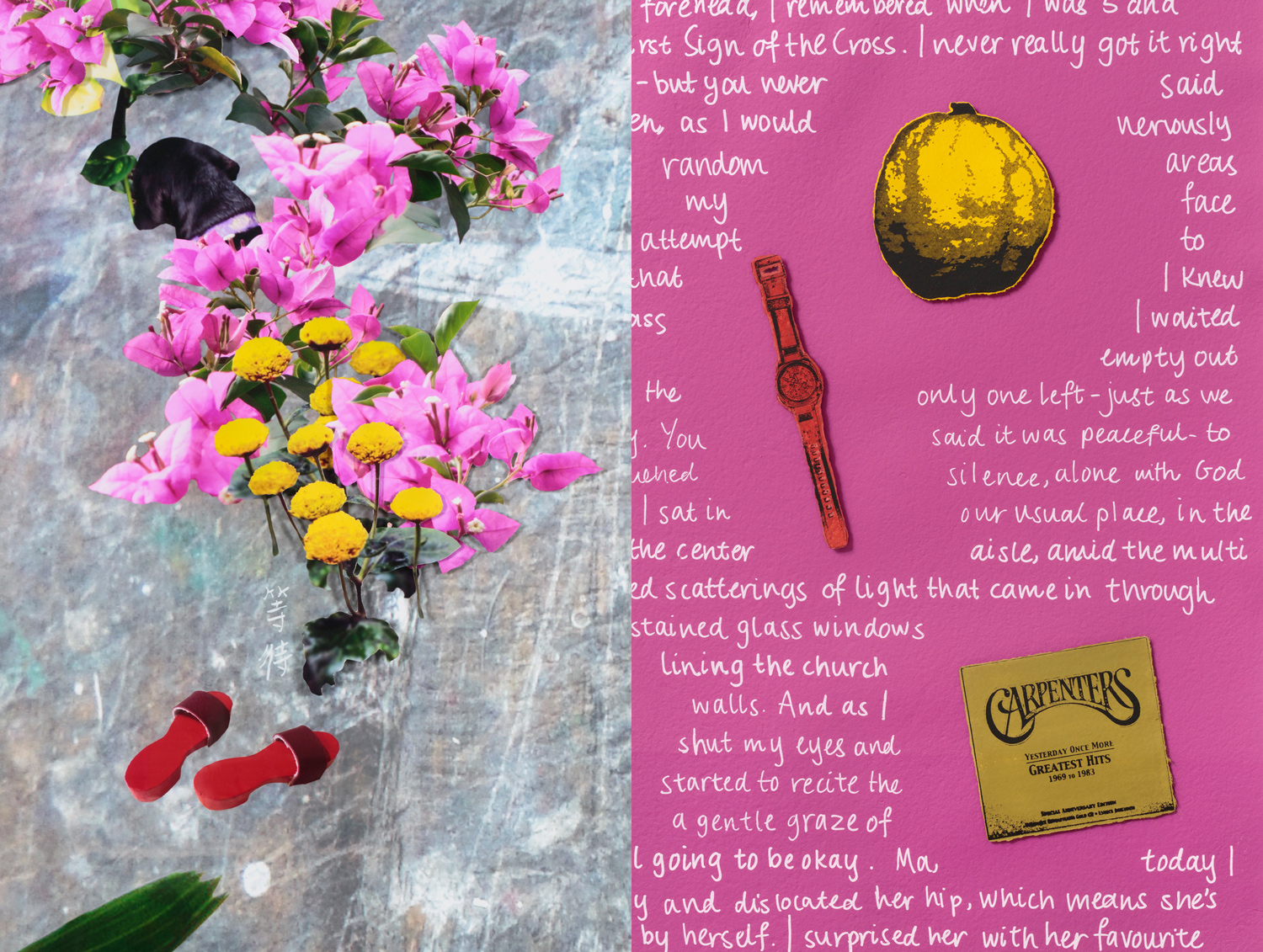

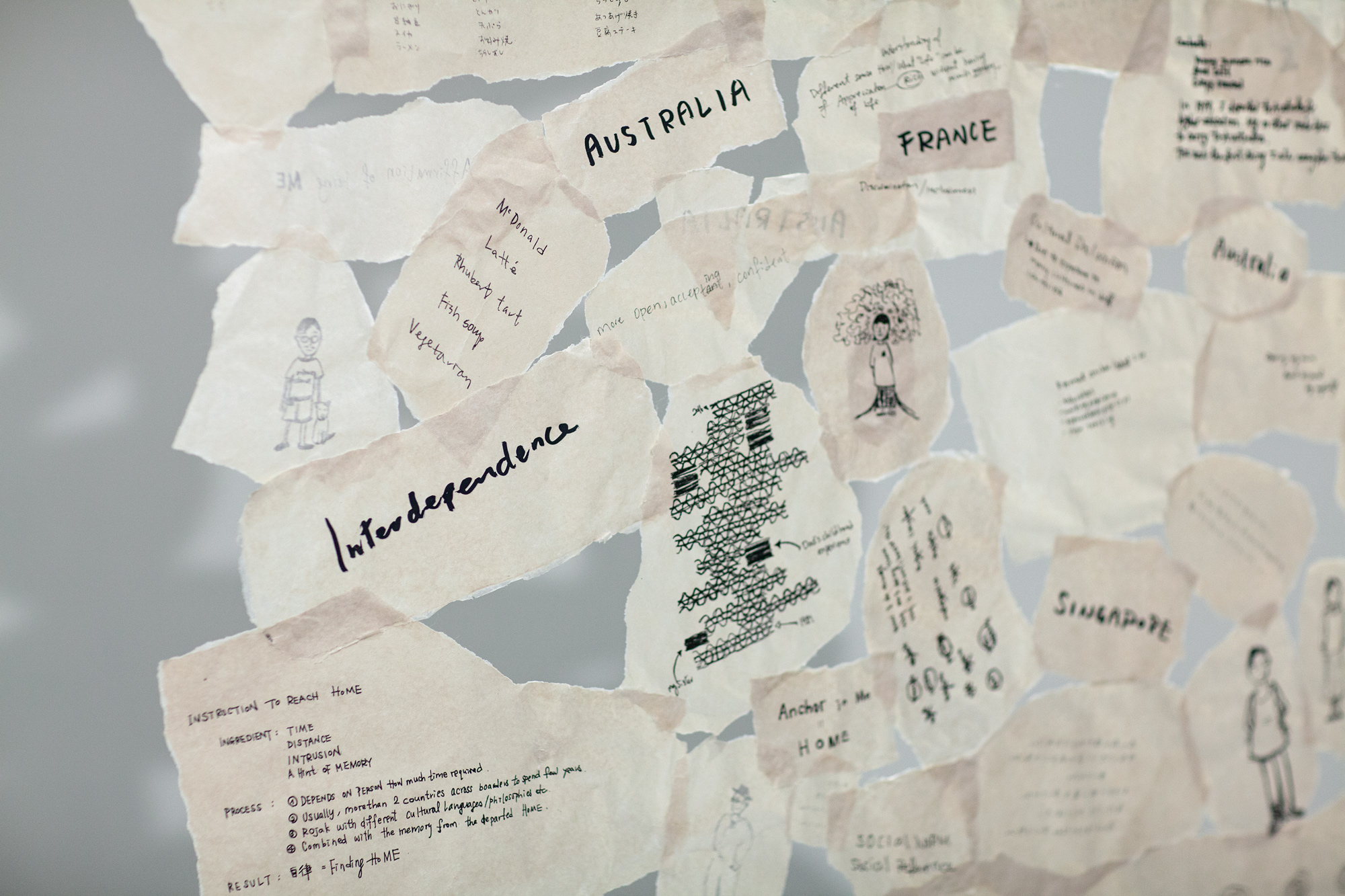

This uncanny knack of making works that work continues in her latest exhibition at

the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI), titled We Are The World - These Are Our

Stories. Heng collaborated with 12 participants over the six-month residency period

to create a single work consisting 24 prints and accompanying digital extensions. In

the first part, she re-staged her performance piece Let’s Chat (1996) with the

collaborators; where they sat around a table plucking the tips off beansprouts and

conversing (a domestic act common across Singaporean kitchens for women of the

household). The second part however, saw Heng taking a step back from doing;

listening, as each participant brought a treasured object to discuss in their private

conversation with the artist. Referring to their sharing as “performances”, the act of

listening on Heng’s part took centre stage, and the resultant prints and papermaking

were created by them under her guidance.

When we met, her hair was tied in the usual two braids that hung past her shoulders,

a look that has become part of Heng’s signature. On paper, I was conducting an

interview; but as our conversation meandered, a thought crossed my mind that

perhaps she wears her braids as part of an aeonian performance—an invisible

mountain of beansprouts between us.

I first encountered your works during your solo exhibition in 2011. For me, it was also

one of the first solo exhibitions helmed by a female artist. Do you feel that the role of

the woman has changed?

Whether in the world or in Singapore, it is still a very slanted situation. This

patriarchal culture has been there for ages and stubbornly hangs on to its power.

Unless lives and values change, the art scene will not. Art doesn’t have—although

some people think it does—the power to effect immediate change. It takes time for

generations of people to understand.

Your works deal with issues such as the loss of history and culture. Are these

themes still prevalent?

They are important because they are very much related to memories. I deal

dominantly with the issue of identity, negotiating my space in this drastically

changing world. Especially in Singapore where we have barely had independence

for 50 years. I am 65, so my life coincided with the process. There is much so

emphasis by the government to induce a certain kind of national identity, and the

result is at the expense of many individual lives. I am one of them, and so are my

parents’ generation. I asked myself—who am I, and where do I position myself here?

There are so many issues at stake, and this also made the practice a lot more

serious for me, as I realised why art is so important.

You have also been a part of Singapore’s theatre scene. Are there clear boundaries

between the different things you do? What other activities do you pursue?

I love plants, and I meddle a lot in the garden. I love cooking, but I’m lazy to do that.

[laughs] Eventually, when I retire, I will probably cook more. My mom is very good.

We are Teochew and I want to learn her way of cooking before she goes. In my

collaboration with her, I realised the way she understands material, what she uses

and how it relates to taste is part of her art practice. When I was creating works, I

appropriated these. Some of the sculptural forms I made came from her everyday

wisdom. She used to iron our uniforms very well. She told me how to make starch

from flour, put the clothes in water, dip it in so it’s starchy, hang it in the sun, and

when it’s almost dry, iron it. People think that my mom doesn’t know art while I am

trained, but after going through these, I realised I was learning and taking a lot from

her. These processes, how she deals with material, how she solves her

problems—this is basically what contemporary work is about. You bring up issues,

problematise it, and you find solutions.

"It is often art forms that don’t belong to the centre or mainstream that create opportunities and open up approaches, which others then appropriate. I love this kind of approach, it requires you to have a kind of courage to try it out."Amanda Heng

And I guess this approach of learning from someone and making it into something tangible is similar to your works on show. Were there some surprising things that you learnt along the way?

The most surprising thing was that in re-staging Let’s Chat, I realised that the more important thing was to listen. If I don’t listen, I wont be able to create anything because the story has to come from the participants. Within the timespan I had to figure out the significance of the object and the relation, and maybe bigger issues that surround it. An object is no longer neutral because it is passed down from someone, so there is historical and political context. Sometimes these objects encompass many different values, and we need to pin down what are the most important things for the particular person who inherited these objects? And to what extent is this person willing to reveal too? I need to know how to prompt them to talk about these. This listening becomes important; it’s quite an irony because we say “chatting” but you realise it is an exchange of talking and listening—and both are important.

Maybe art should listen more.

Art is very much how we develop a spirit of paying attention to things. When you deal with material you pay attention to that material and then develop a relationship with it through understanding. You find certain qualities or rhythms because you understand enough of the material and discover things through that. Same for me, the people I work with and their stories are my material. My practice has always been very people-oriented. It is exciting and challenging for me to discover art existing in the world rather than thinking we are gods creating new things. We might be using “new” material, but we are drawing upon knowledge passed down from our memory.

You mentioned earlier during the tour that you used QR codes to engage the younger generation. Can you share about this aspect of virtual space and what it means for your work?

If you remember the bare bottom piece [Singirl], it was done here in the form of a print. The residency was very short. I went back [to my studio] not feeling satisfied because the extent of contact with the public was so limited. I was thinking hard how to make this work ongoing, and thought of the website. It allows people to not be confined to the exhibition period, time, or country— a website open to women across the world. Anytime they want to be part of it, they can take action. And that’s how virtual reality and space came in.

Art deals a lot with space. It starts with a 2-dimensional wall space and you create a sense of perspective within that limit, then you have 3-dimensional sculptural forms free-standing, then installations addressing the physical space. Performance deals with time-space, what happens from now till then. So we are dealing with different kinds of spaces. When we introduce new technology it becomes part of our everyday life, and yet we just use it because it is there for us to use. We ought to understand how it comes about and how to take advantage of it, rather than being ruled by it. That’s how the website became important. At the same time, I was also developing an online archive for art by women in Singapore, so I needed to know all these things.

This series is vastly different from your previous works. Is this a phase of transition

for you? Also, as we are at the start of 2017, how do you see the process of making

art in your personal practice transforming?

Actually the forms might be different—the final visual form might look different—but

performative principles are very much intact. Performance deals with time-space,

creating work as an experience, not an object. It is not about the object, but the

whole process. In this case, the experience of the 12 people. The QR codes allow

other kinds of processes, such as outside engagement with the public to be shown.

So it creates many different spaces, challenging the participants to recognise that

apart from being participants they are part of the bigger general public.

Many say performance art is at a dead end, that it was only exciting in the ’60s to

’70s and very much to do with activism. But the approach to performance art has

been mutated and hijacked by formalists, modernist artists, and people who create

objects. These aspects of using processes, addressing time-space and participation,

have become exciting in formal work. Whether we like it or not, if you look at art

history, all the big artists have been involved in performance work before. When we

look at the discussion of all these different art forms, I wished there wouldn’t be

hierarchical judgment. It is often art forms that don’t belong to the centre or

mainstream that create opportunities and open up approaches, which others

then appropriate. I love this kind of approach, it requires you to have a kind of

courage to try it out. Experimentation is the thing, and failure is part of it. This is

even more important in this era where nothing is guaranteed anymore. Change is the

main constant. And how do we prepare ourselves and keep up, how do we go about

continuing and engaging with these changes? Art is at the forefront, kind of figuring

out the path for us to follow.

For 2017, looking at the way I develop my practice, it has never been about

producing works quickly; I like the sense of process and I want to do it even more

deeply. We have a lot of rich material here, just talking to another person is already

so rich—so how do we go about doing it, taking very slow and small steps, but going

deep in? I feel that this is the way for us to find an anchor in this drastically changing

world. Human nature needs that kind of space, to have time for reflection. The faster

things go, the more you need it.