As ISIS marches lockstep along its path to not just a self-proclaimed caliphate, but possibly global prominence, the world has repeatedly reeled from the corollary rise of violence carried out by lone wolves and trained militants alike. Acknowledging that fashion (and art for that matter) does not exist in a vacuum, Marine Serre responded to the prevailing cultural dissonance she witnessed following the terror attacks in Brussels and Paris through her critically acclaimed graduate collection “A Radical Call For Love”, winning her the coveted LVMH prize earlier this year. Much like Grace Wales Bonner (incidentally a winner of the prize as well), Serre represents the promise of the fashion industry, offering a window into the burgeoning creativity of the future.

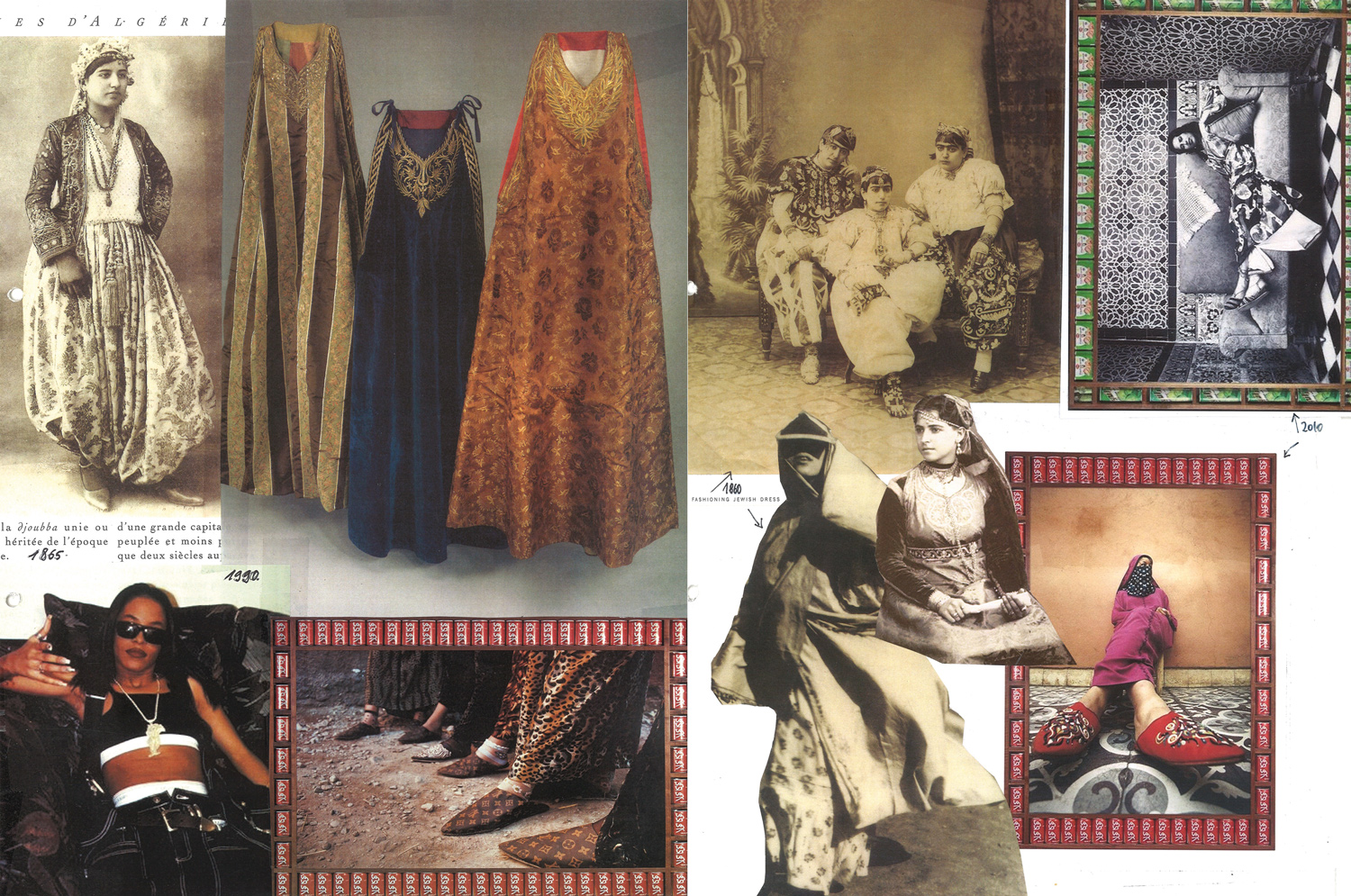

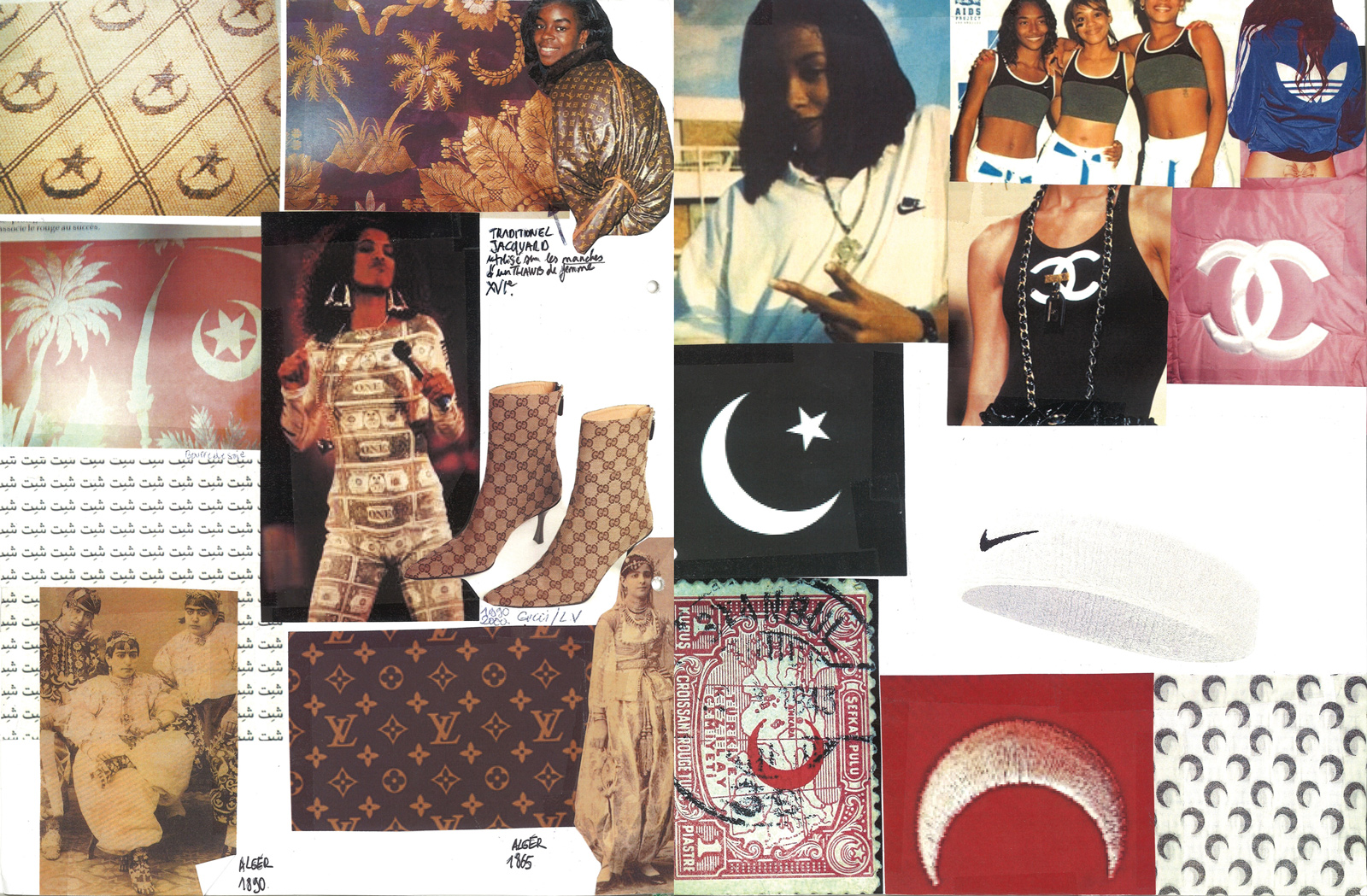

In “A Radical Call For Love”, Serre mingles sportswear silhouettes with 19th century Arab influence—athletic shapewear billowing out into voluminous taffeta dresses and the use of the crescent moon as an iconographic riff on athletic logomania. In a sense, Serre is not simply “radical” when it comes to her experimental approach to design and her futuristic aesthetic, but also in her ideas and the conceptualisation of her clothes. Without being overtly political, Serre alludes to a possible way forward for a world that has become painfully resigned to the status quo—if we were to momentarily jettison pre-conceived labels and categorisations in favour of radically embracing our differences, there remains a window of opportunity through which we could come to a consensus and respect our underlying unity.

How did you end up in the fashion industry? Did your experiences growing up feed into your journey to becoming a designer?

To end up in fashion: this is a nice of way of putting it! It’s a never-ending job to analyse how I ended up at this point—but I’ll try. What was important was my upbringing in a small hamlet in the countryside, far away from the urban centres of fashion. The long distance from everything fashionable as a child led me to greatly admire the beautifully dressed city ladies—like a sort of hyperactive contemporary Cinderella [laughing]. But at the same time, precisely because I did not grow up amidst fashion, my imagination ran very wild and free. So, I developed a very distant but free desire towards art and fashion, soon starting to dress up as extravagantly as possible, and I gradually fell into fashion, deeper and deeper—it started as child’s play, then as a collectionneur of vintage, then reworking my finds, and then as a student taking advanced technical courses in Marseille. Then, I applied at La Cambre, and from there, here I am. To explain how that happened further: I was brought up with a strong work ethic, and have simply always worked a lot... Finally, there are many other things of course: my travels, my experiences in cities like Brussels and Marseille, and my friends.

"I think growing up far from Paris and the fashion scene, both culturally and geographically, still provides me with some naiveté in the way I see things, imagine them, and process them. And I feel this really lies at the bottom of my creative perception."Marine Serre

Which experiences have shaped your creative perception the most?

It is impossible to single that out in any flat way, I think. Can you tell me where one experience stops, and another begins? I don’t think so! [laughing] Experiences are ultimately all intertwined. If I must single out something, as I already mentioned: I think growing up far from Paris and the fashion scene, both culturally and geographically, still provides me with some naiveté in the way I see things, imagine them, and process them. And I feel this really lies at the bottom of my creative perception.

In a sense, the naiveté that you speak of, comes from a lack of exposure, which I guess is only relevant at the beginning of the journey. How has that changed for you over the years as you travelled more, gained new experiences, and grown more seasoned?

When I lived in Marseille and Brussels, the naiveté was more of a reclaimed naiveté. Lately in Paris, with all the attention, it is probably growing into a radical, almost militantly kept naiveté. But it’s still here! It takes effort to keep it safe, but anyway...

How then does this naiveté—a state of mind—translate into your designs?

On a more real level, in terms of style, I work a lot from contrast and tension between sportswear and couture—and this you can read along the same lines. Working in high-end fashion together with sportswear references is not entirely new in the fashion industry, but the depth of the schizophrenia is often overlooked, I think. On the one hand, there are sportswear, workwear, or other functional fabrics and garments, with popular, working class, mass culture references, and mass production processes. What happens in high-end ready-to-wear, couture or couture-like fashion is something very, very different—luxury, individually worked garments for refined urban elites. The tension flowing from these contrasts is really moving to me. Appreciating elements of both, while ignoring the gap that lies between the two, being able to work freely and combine things from both sides... this goes far beyond aesthetics. It also connects to a socio-political stance. And it is challenging in terms of “market analysis”: both classic luxury customers and sportswear customers must be given something very different than what they are used to. They also need something they really enjoy and feel comfortable wearing. Complex and expensive dresses can relatively easily make gestures towards sportswear or workwear, but also, to not become dishonest, the overall collection then also needs to at least offer some very plain and affordable pieces. These then must be sharp and simple but in turn remain coherent with the high-end dresses and include more complex creative twists. This entails rather difficult and unusual demands for both mass and traditional luxury production processes and manufacturers.

I understand that you have worked under Sarah Burton (for McQueen), Margiela and Dior. How have these different experiences influenced your creative process, if at all?

Through looking, one learns. Like every good designer, I picked up and still pick up different moves and techniques from studying the garments of others, or from vintage. Then I repeat and repeat, until I reach a certain control—and along the way, I develop, move, experiment, and rework them into something different and new. That being said, when I really try to be very honest, it is again really difficult to pinpoint how certain experiences shape my “creative process” [laughing]. What I do is simply what I do! And I really want to keep it that way. Precisely, when I would be able to answer your questions, when I can easily pinpoint something I make as coming from another designer, I am not happy with it anymore. I think any good designer is a hyper sensitive sponge, but then also works negatively in this respect. This is why working in fashion is so hard sometimes. To create something new, you have to put things you like aside—not because you don’t like them anymore, but on the contrary. Especially because you like them, you need to move away from them to make something new out of what has inspired you.

Your collection “A Radical Call for Love” is stunning and poetic. What was your inspiration behind it?

I’m glad you say it is poetic! I’m, of course, also glad you say it is stunning. As for poetic, I hope you agree that “poetic” does not mean for you some weak-hearted romantic nonsense.

portrait-of-1876-in-algeria--hassan-hajjaj-in-2014.jpg)

Of course not. I think of poetry as a loose economy of words—words that with their accompanying subtext, when put together, tell a much longer and complex story than their aggregate implies. They don’t just read beautifully, but have the capacity to open up another world for the reader. In the same way, my reference to poeticism stems from the way your collection brings together the idea of Arabic culture and modern sportswear (two very disparate ideas in my opinion), and melds them together so beautifully into your own narrative.

To quote Martin Luther King about love: “I’m not speaking of that force which is just emotional bosh”. “A Radical Call for Love” emerged during a period when Paris and Brussels were in shock after the attacks. With these events in the background, my reference to “love” was not meant as some soft response (hence the adjective “radical” of course).

At first, as I mentioned already, the main inspiration behind the collection was to blend together sportswear and couture-influenced ready-to-wear in a new and more serious manner. This sense was already there when the attacks took place. Both happened right next to my door—the one in Paris when I was interning at Dior, the other when I had just started with the collection back in Brussels. You might have already guessed: I am perhaps a hardworking, but also very sensitive kind of person, and the events impacted and really disoriented me. To continue to work in fashion while pretending that nothing was really happening outside of it didn’t seem right. As I mentioned earlier, as I try to be a good designer, I work like a sponge of my environment, and I started absorbing Arabic and Turkish historic garments and techniques around this time. In Brussels, the air was full of anger and rebelliousness at the time, and I especially came to be inspired by the many girls who move between sportswear and traditional references every day, knowing what they want, hyper-sharp all the time, and in fact extremely contemporary.

So, in short, I came to discover that the sportswear/couture contrast and tension I was already working with only became even more relevant and interesting! Both aesthetically and socially, all things fell into place. Sportswear pieces like slick training technical jersey t-shirts made a perfect match with an abundant use of fabric in the green striped ball skirt, for example, creating at the same time a radically minimalist, feminine, as well as very comfortable look. Then the crescent moon offered itself as the perfect riff on the sportswear logo—or the other way around. All kinds of different directions and sensitivities, I think, were touched upon very well. Without being explicit on any political message, the garments merged and fused references that are normally divided by different conceptual frames. A hybrid sort of garment developed, that was far more futurist- like than I had first anticipated, and I still think this is amazing—although I am also really looking forward to move on to new work now!