At the root of it all, the one thing that typifies a cult is enigma. Be it a person, or an idea, it is this sense of mystery that first draws us to something, and then catches our attention, again and again. We don’t often understand these cults, and in part, that is what unceasingly ensnares our imagination. As a person, and in his ideas, Hedi Slimane embodies such a cult, and in doing so, has created—most undoubtedly and knowingly—his own troop of diehard followers.

Slimane’s rise followed by his disappearance, and then return, to fashion has been widely chronicled and studied. His influence, however, was already apparent from his time as creative director at Dior Homme, where he all but singlehandedly ushered in the skinny men’s silhouette with his super-tailored suits, to critical acclaim. At the height of his success, he left the world of fashion to focus on his photography projects, the result of which can be seen accompanying this article.

When he returned to the helm of Yves Saint Laurent in 2012, sixteen years after his first tenure, he was welcomed with fanfare but also outrage as he renamed the brand’s ready-to-wear line, overturned the atelier, and partially moved his studio to Los Angeles. Dividing the industry along the way, this l’enfant terrible appeared to completely disregard one of the fashion world’s most long-standing and respected houses mere moments after his long awaited comeback.

We can never be certain about what Slimane is truly thinking, but we can guess; was he actually bringing back the essence of Yves long gone? Like Yves, Slimane’s collections—his first few, in particular—have not been universally well-received. In the 1970s, Yves showed a collection that drew references from the Nazi occupation of France, prompting a collective outpouring of outrage from the press; while less politically offensive, some of Slimane’s initial 90's grunge-inspired collections have been likened to Topshop-knockoffs at couture prices.

Hardly uplifting, but perhaps what both Yves and Slimane have in common is that they couldn’t care less about what people think. While other designers have been known to break after a bad review, only a handful would consciously choose to seat the top editors and writers in the back rows of a show—unless they are so intent on pushing their own agenda and vision that they are unstoppable in their cause.

Love him or hate him, Slimane’s collections have proven to be unfalteringly sellable. Without delving into the rights and wrongs, Slimane was one of the first designers to realise that the image is the product, and he has staked claim to an unmistakeable, identifiable look of nonchalance, youth, and recklessness that has delivered an entirely different legion of fans into his back pocket. And perhaps that is also why, whatever your opinion of him, you’ve got to admit that this man’s got guts. For it takes guts to upheave an entire industry based on fantasy, narrative, and the unattainable; the Saint Laurent girl or boy is as much identified by their tags as their attitudes.

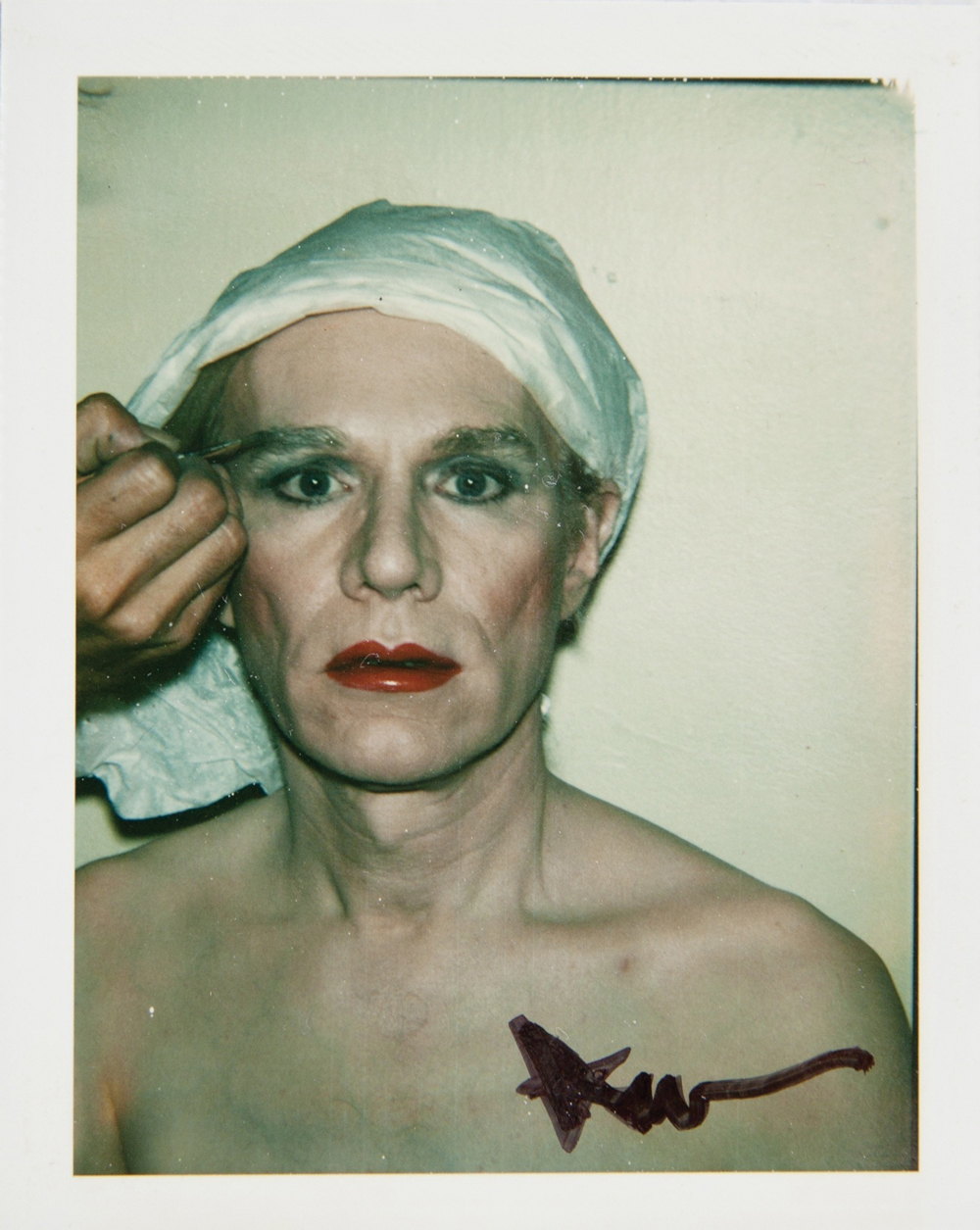

When it comes to attitude, Slimane finds kinship in music. With the way music can vividly archive the zeitgeist, it is fashion's legitimate sister. It is also an integral feature of the Saint Laurent brand and it is no secret that Slimane is heavily influenced by and involved in the underground music scene. His evocative, black and white portraits of famous musicians and their progeny are proof of his fascination and obsession. Frances Bean Cobain, Sky Ferreira, Pete Doherty, and The Garden just some of the names he’s photographed over the years; his fashion collections sometimes seem like a chronological timeline of music subculture, from Teddy Boy to glam-rock, eschewing separate storylines for a sense of continuity.

What is it that draws Slimane to music? Perhaps the same things that draw him to fashion—the fetishisation of youth, the celebration of immortality, the fleeting impermanence of fame. He brings the two worlds together in his ultimate daydream, which he also employs to push new bands into the limelight. The Wytches, Cherry Glazerr, Bass Drum of Death, and Skinnybones, to name but a few, who, in turn, contribute to the devil-may-care veneer of Saint Laurent. The Music Project sees some of these musicians—Joni Mitchell, Daft Punk, Marilyn Manson, and Courtney Love are some of the recent stars—styling themselves in clothes from the brand; ever the all-rounded multi-tasker, Slimane then directs and photographs them, the iconic images almost becoming campaigns in themselves.

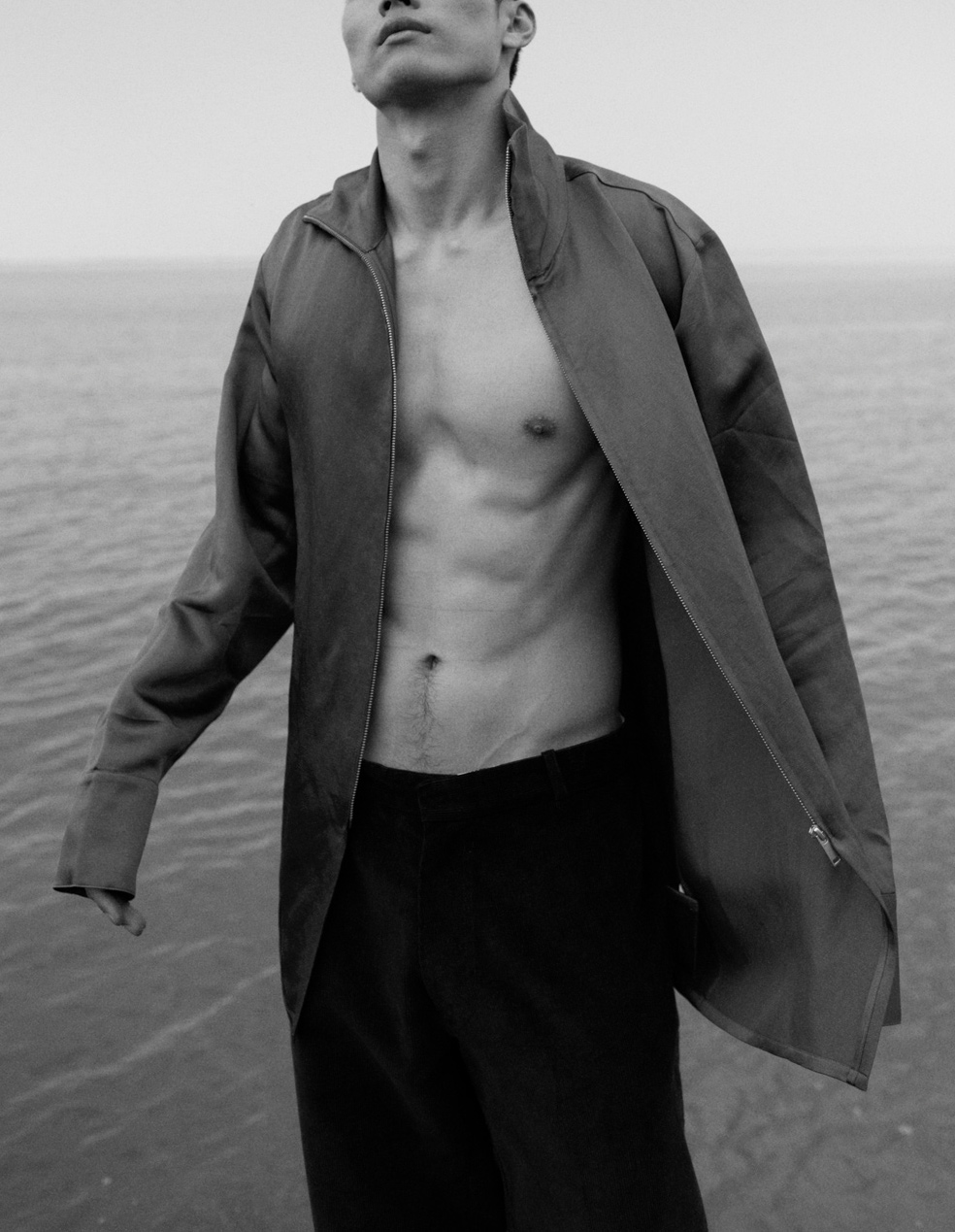

Yet for all his careful considerations about image, Slimane doesn’t let his technique and skill slip. The same critics who dismiss his collections on the runway have been known to come around when they see the garments up close. Even with its associations with street wear and youth culture, Saint Laurent’s clothes are exquisitely, lavishly made. The menswear atelier established by Yves in the 1960s closed in the 2000s, and upon Slimane’s return, a new, unisex atelier was created. He overhauled the production and came up with new specifications for tailoring; almost half of the grunge pieces from his F/W 13 line were handmade in the atelier. All these point to the same innate hallmarks of the Yves Saint Laurent brand and man—the questioning of the meaning of luxury, the undermining of the fashion industry by combining street fashion with couture techniques, and most overwhelmingly, the desire to design for and dress the current generation.

So popular are some of the pieces that the brand has launched a permanent collection, available every season, made up of the basics of the Saint Laurent wardrobe—the quintessential lambskin leather jacket; low-waisted, ripped skinny jeans; calfskin low-heeled boots; and cashmere and silk paisley bandanas.

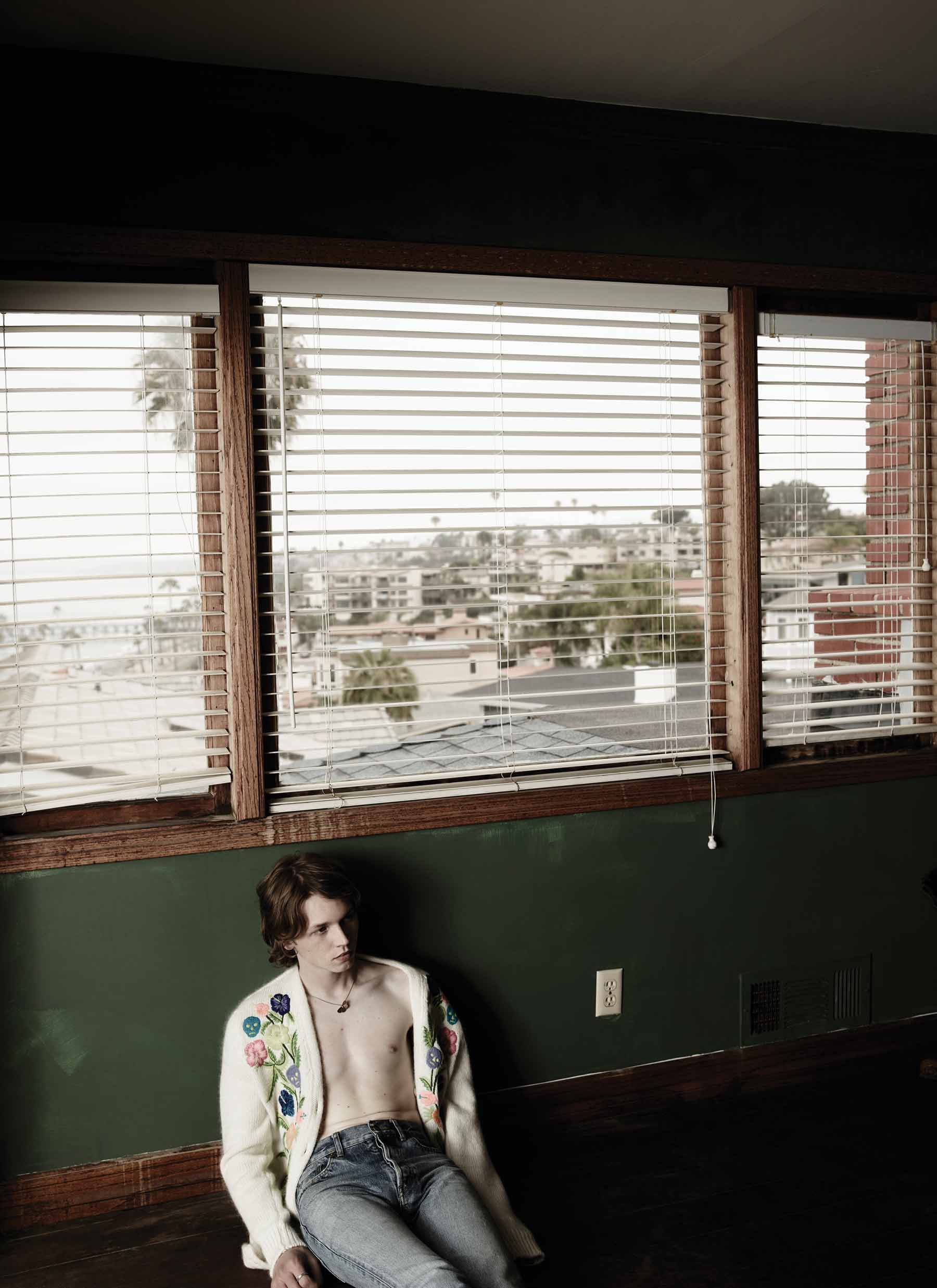

Slimane continued this ambisexual slant in his latest collection, titled Surf Sound: A Tribute to Contemporary Californian Surf Music Culture. Androgynous waifs walked the runway dressed in patchworked leather jackets, beat-up sneakers, mop hairstyles, frilled socks, oversized knitted cardigans, tattoo neck chokers, babydoll dresses, and destroyed plaid and denim. It was a mix of pieces that looked like they were pulled from thrift stores and suburban wardrobes, and that shouldn’t have worked, but looking at the entirety of the collection—or perhaps more so the street-casted group of misfits and outliers—the cult of Hedi Slimane couldn’t have been any more apparent.