It goes without saying that travel today is a whole new world unto itself. It takes place at unprecedented speeds and scale, and nearly all parts of the world are within reach. Travel is increasingly affordable and necessary; practically involuntary. It also now consists of so many inconvenient, regulated motions that it seems to be approaching the end of its novelty. How does the ubiquity of travel shape our contemporary lives and identities? If there is a mode of self-definition produced by a person’s trajectory rather than station, then the journey is a site of becoming, a common ground upon which we all test and invent ourselves.

As the persistence of the literary genre of the bildungsroman—the coming-of-age story—demonstrates, the journey of becoming is a perennial operation. Travel is complementary to fashion in that instead of accessorizing oneself through arts, decoration and poses, one pursues new surroundings and tries each one on, consuming its qualities to alter one’s disposition and appearance into a seemingly effortless, serendipitous byproduct of being away; a souvenir from recent adventures (the talismanic properties of a suntan). The decision and commitment to leave here for there demonstrates one’s critique of the status quo as well as a desire and faith in the unknown, sentiments that we share with pilgrims and wanderers in however small amounts. As we practice the art of departing, we also learn to play host and guest, to exploit each momentary encounter with worldly things, while all the time paradoxically collecting and claiming them for our own, fixing them in our minds, furnishing our interior worlds.

Thus travel is a creative act, in which the medium is the itinerary and the material is the world itself. To travel is to engage in a mode of praxis that great thinkers and makers have exercised throughout history. Just as the predecessor to the moving image is in fact the cinematic blurs from the window of a moving train, the setting of oneself and the world in motion is often the initial genesis of art. Artists have always taken off to establish aesthetic positions and chart their sensibilities, conducting an exchange with the unfamiliar in order to produce new ideas. As Rachel Whiteread once said, “London is my sketchbook.” Practice occurs between person and place.

So now we might revisit the works formed en route and perhaps better understand why and how we move in this cultural moment. There is the sense that historical adventures and their experience of some authentic strangeness and novelty is already lost to us, and future generations. What is being mourned is not so much these places and their qualities but the sensation of discovery. Or is this a false sentiment? Have we always been guided along through by the artificial visions of others? To travel is to participate in an ancient ritual, and modern travel has in fact always been a heavily mediated operation. It could be said that the bildungsroman genre perpetuates itself; we travel because others have travelled before.

What follows is a collection of bildungsroman that illustrates modern travel in its various manners throughout modernity. Addressing the contemporary traveler, this writer asks that they reconsider the ways they travel in terms of these praxes, of those who have gone ahead of us to escape, explore and subsequently invent.

THE FANTASTIC ADVENTURE

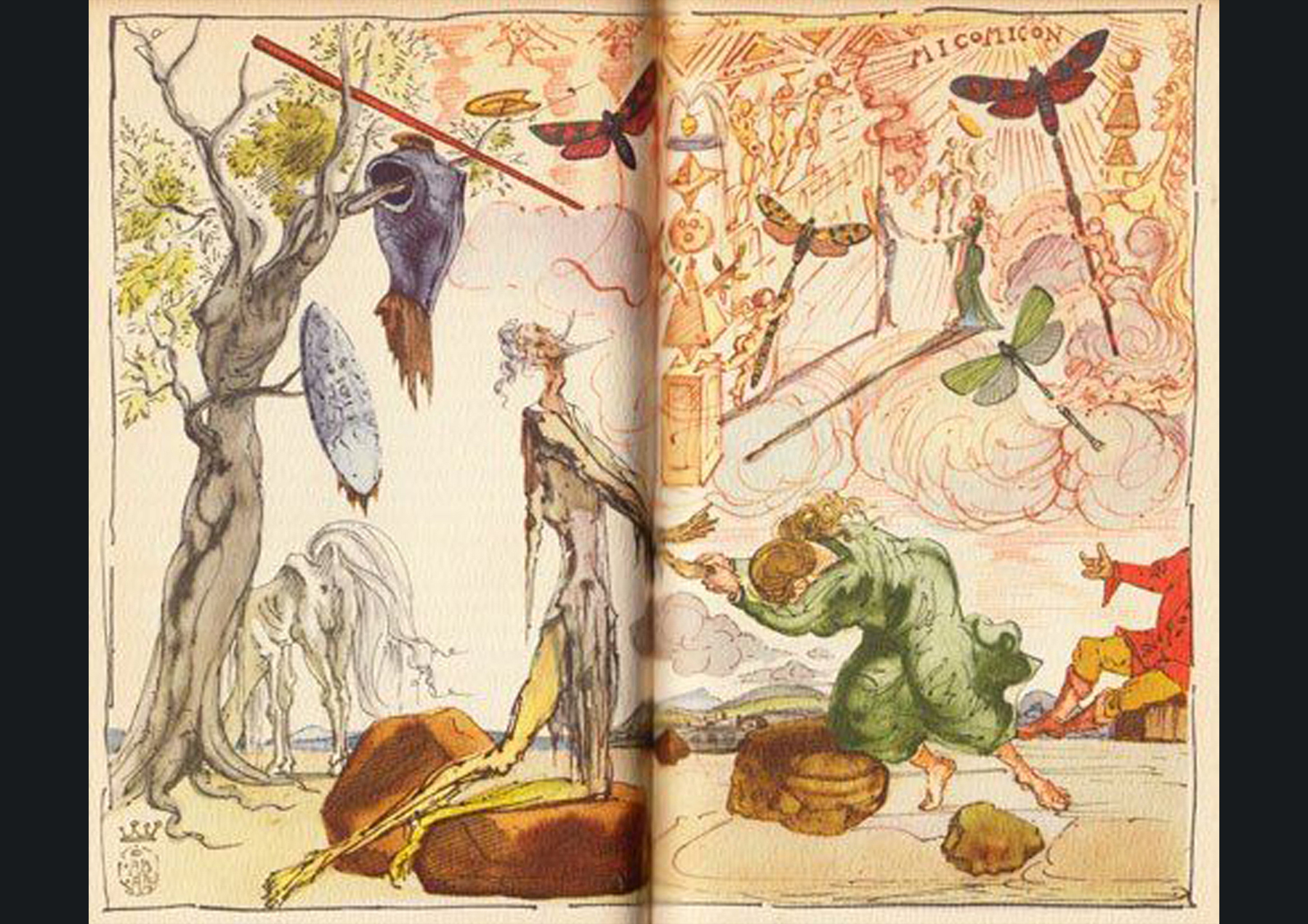

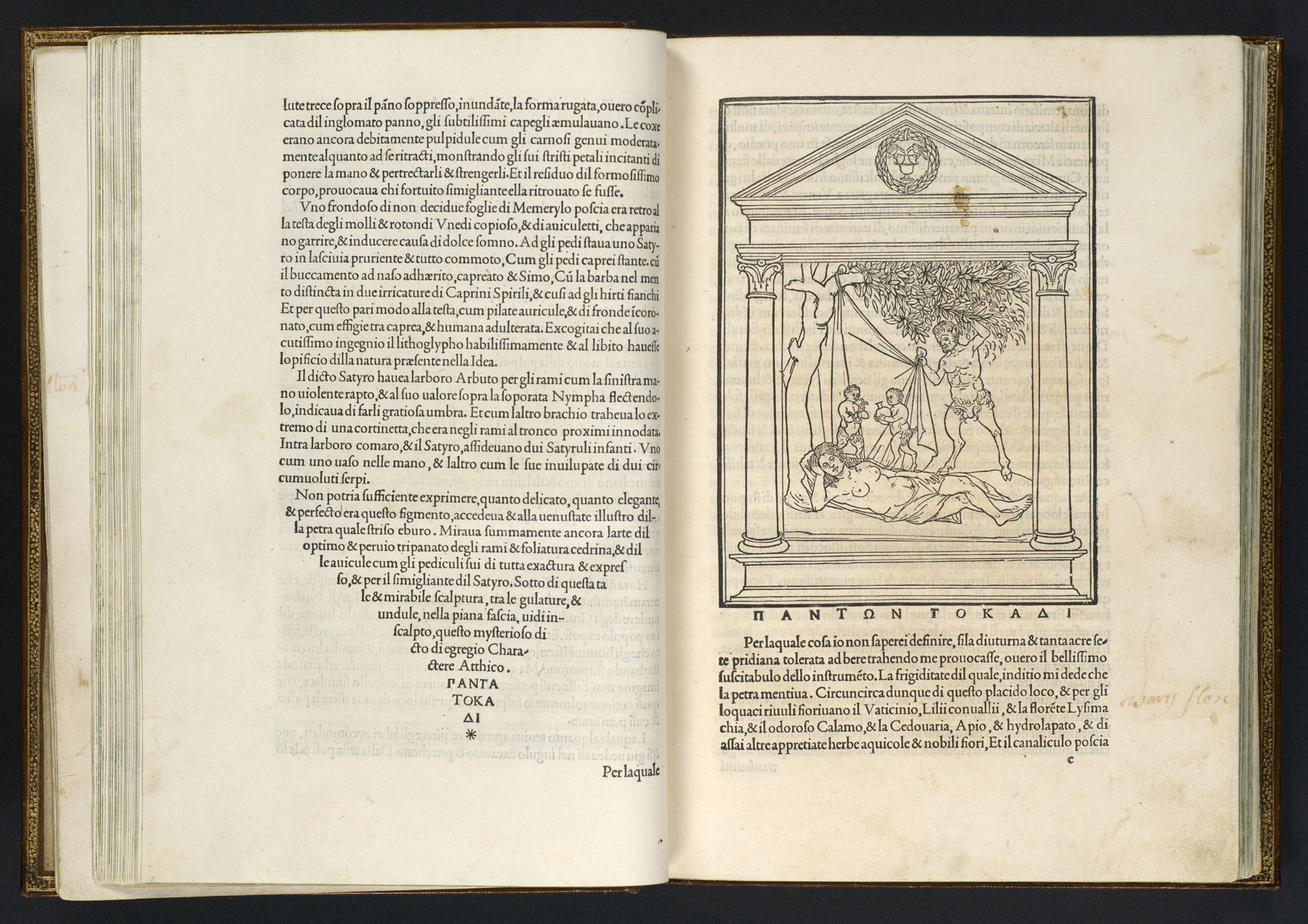

The Age of Discovery saw the publication of two popular fictions, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love In A Dream) first printed in Venice in 1499, and the Spanish classic El Ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha (The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha) in 1609. The Hypnerotomachia was set in Treviso of Veneto, referencing the region’s monuments and iconography, while Don Quixote’s journey takes off from Spain’s La Mancha region and reaches epic closure upon the beaches of Barcelona.

Both authors Cervantes and Francesco Colonna introduce a protagonist who begins as an everyman, a non-hero only made exceptional by his passion for an absent ideal. Poliphilo dreams within dreams of pursuing his beloved Polia—he adores her just as he adores the mysterious structures and rituals he encounters; he is ravished by his journey. Alonso Quixano has instead a maddening passion for picaresque novels and the chivalric adventures they describe. There is little to these simple mortals until they are, by dream or reverie, set loose to embark on their respective pursuits by absolute compulsion. There are hints that in fact both journeys stand for a protest against each character’s reality: Poliphili’s slumber is prompted by Polia’s rejection; Quixano is lost in books and alienates himself from the rest of society.

Within each narrative there is an oscillation between the real and fantastical such that the reader is invited, not compelled, to believe in their super-natural aspects. Each character adopts a decisive naïveté, taking leave of realism to fight with windmills and fondle stone figures. In a sense they each invent the attractions and spectacles along their journey, that charts the obscure regions of landscape as well as psyche. Each text serves as a veiled commentary on an earlier literary genre, from which travel writing draws its imaginative aspect—the allegory; mythological, epic. The modern passion for travel draws from from such experimental metafictions that distill the fervent desires and unbridled imagination of common man away from religious experiences towards physical ground. In its intertextuality and eclecticism we detect an irreverent wish to visit, perhaps inhabit, states multiple and other.

THE STUDIOUS EXPLORATION

In the scholarly tradition of the Grand Tour, Goethe documented his travels to Italy during the years 1816-17 in the text Italienische Reise (Italian Journey), and some two hundred years later Le Corbusier, then still Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, wrote Voyage d’Orient (Journey To The East). Each works is considered a minor, perhaps remote counterpoint in each thinker’s momentous career.

Both writer and architect sought to dislocate themselves from artistic conventions and revisit a truer, original order of beauty. Goethe left the excessively ‘literary’ environment of the Weimar and the Sturm und Drang movement, taking off unannounced from Carlsbad one evening along the Danube to reside in Rome for five months—also visiting places such as the great Lake Garda; passing through Venice’s Grand Canal; observing the Doric temples of Segesta; witnessing an eruption at Mt Vesuvius and lingering in the botanical gardens of Padua and Rome;—seeking out encounters with an energetic curiosity. Jeanneret instead desired the original aesthetics of the near East and traveled further to Constantinople.

Both devoted a precise attention to the landscapes they moved through. Goethe considers the geological conditions underfoot; Jeanneret faithfully sketches even the most modest structures. Goethe wrote: “I don’t seek adventure out of idle curiosity or eccentricity, but, since I have a clear mind which quickly grasps the essential nature of an object, I can do more and risk more than others.” Indeed, both gleaned abstract, elemental ideas to form proto-aesthetic system of thought—as if they finally saw past the horizon and identified a point of origin, an idealized tabula rasa from which the world unfolded.

They did not idle but instead worked intensely en route—Goethe ceaselessly wrote letters and rewrote old works despite seasickness or the distractions of Roman society. The young Le Corbusier penned down sketches and throwaway sentiments that unconsciously set the tone of his lifetime’s work: forms that hinted at an obscure primitivism, permeated with the screeching whiteness of Southern light.

Each journey could be credited as the locus of their visionary oeuvres that seemed sensational in their lifetimes, and remain ingenious up till now.

AWAY STATES

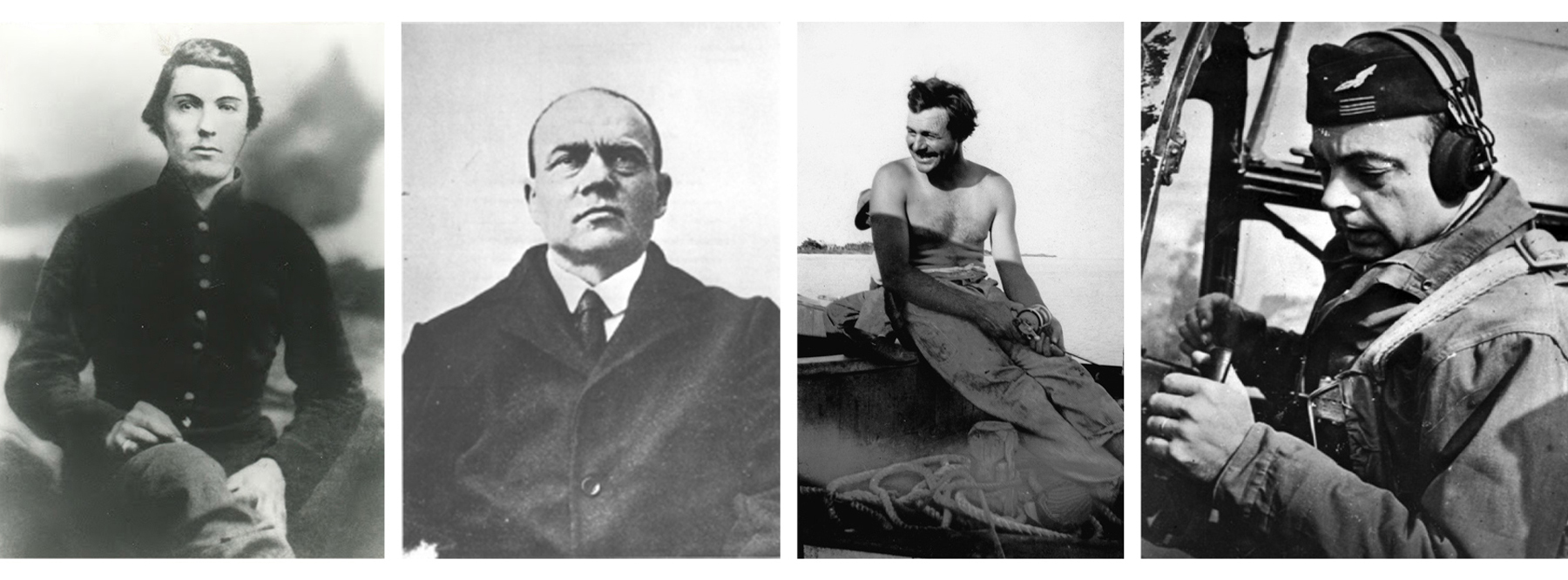

In the tumultuous times of the early 20th century, young men set out for foreign lands for intents and purposes that were less than idyllic, often arriving at unforseen situations and cruel awakenings. Gertrude Stein called them a génération perdue—a lost generation.

In Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel Heart of Darkness, the protagonist Marlowe set off from London for an errand; from Thamesmead to the western coast of Africa to the Congo River. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry worked too, as mail pilot for Aéropostale: Terre des Hommes (Wind, Sand and Stars) charts his expeditions between the airports of Europe, Africa and the Americas, crossing the the Andes and the Sahara; it concludes with his reports on the Spanish Civil War, where he met other writers such as Ernest Hemingway, who initially moved to Paris as a Toronto Star correspondent. The anthology The Moveable Feast documents the expatriate community’s activity and society; within their bohemian apartments and outside at the Ritz Bar or Left Bank bookstore Shakespeare & Company, through the irresistible Jardin du Luxembourg...

This scattered intelligentsia created a constellation of romances, attitudes, ideas and art. The modernist spirit for an abstract and timeless beauty formed from this uprooted and—in Walter Benjamin’s use of the term—barbaric generation: naïve and numb to the grand narratives of old that fell apart then in thunderous, destructive waves. Their economical, crisp literature concerned itself with fashioning some way of bare, transient life. The base aspects of life—hunger or thirst or weather, took on metaphysical value. In Hemingway’s words: “I’ve seen you, beauty, and you belong to me now, whoever you are waiting for and if I never see you again”...

But for the haunted Kurtz and the poet Dino Campana, travel was an irrevocable act that severed them from ordinary life. Campana, a compulsive wanderer, formed the blazing visions of Canti Orfici (Orphic Cantos) as he drifted from Marradi through Bologna, Genova, across the Atlantic to Argentina.

Even as the strangeness of new places brings solace, it also breaches the limits of reason to attain a sublime and horrible clarity.

NOWHERE

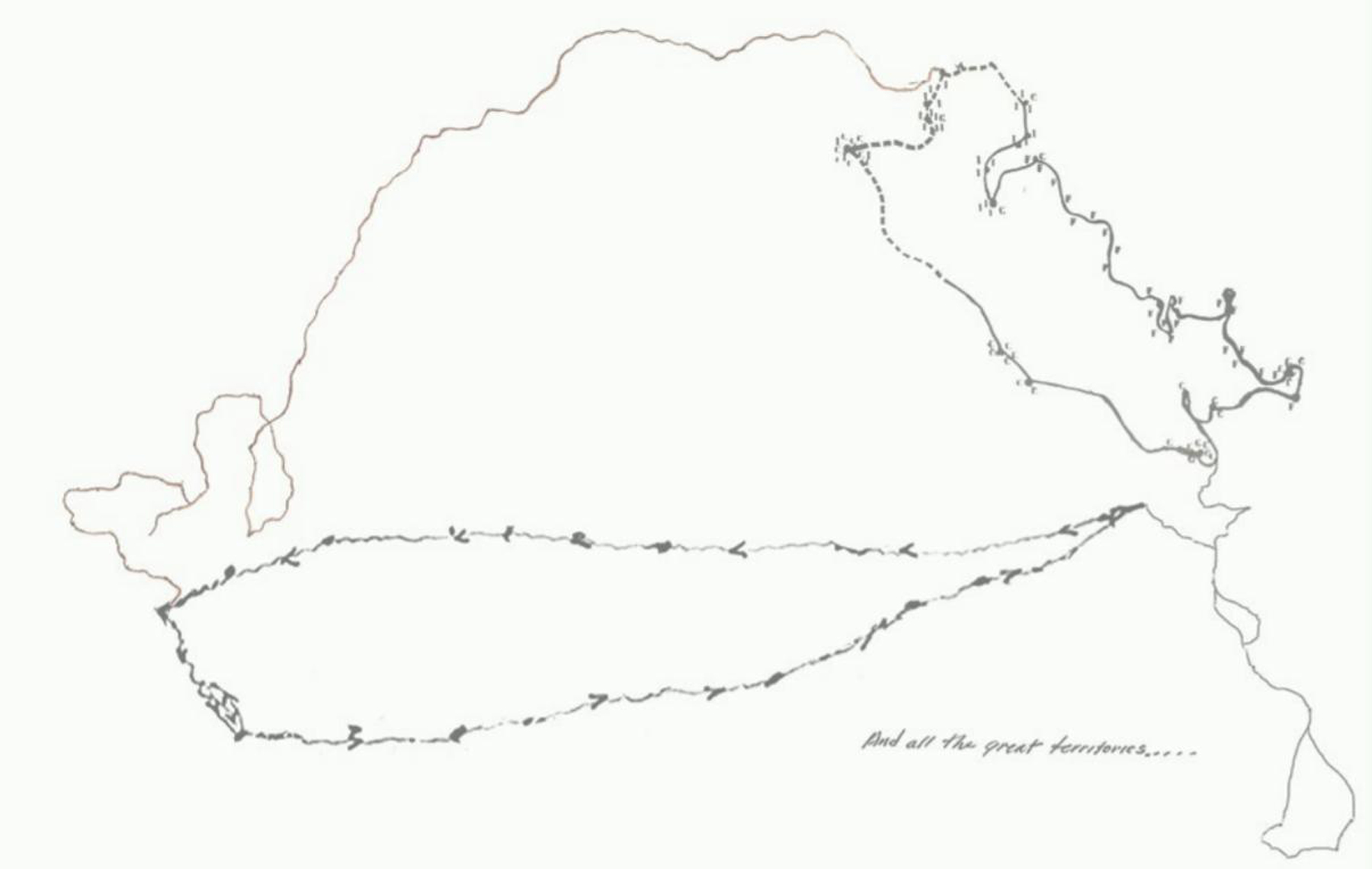

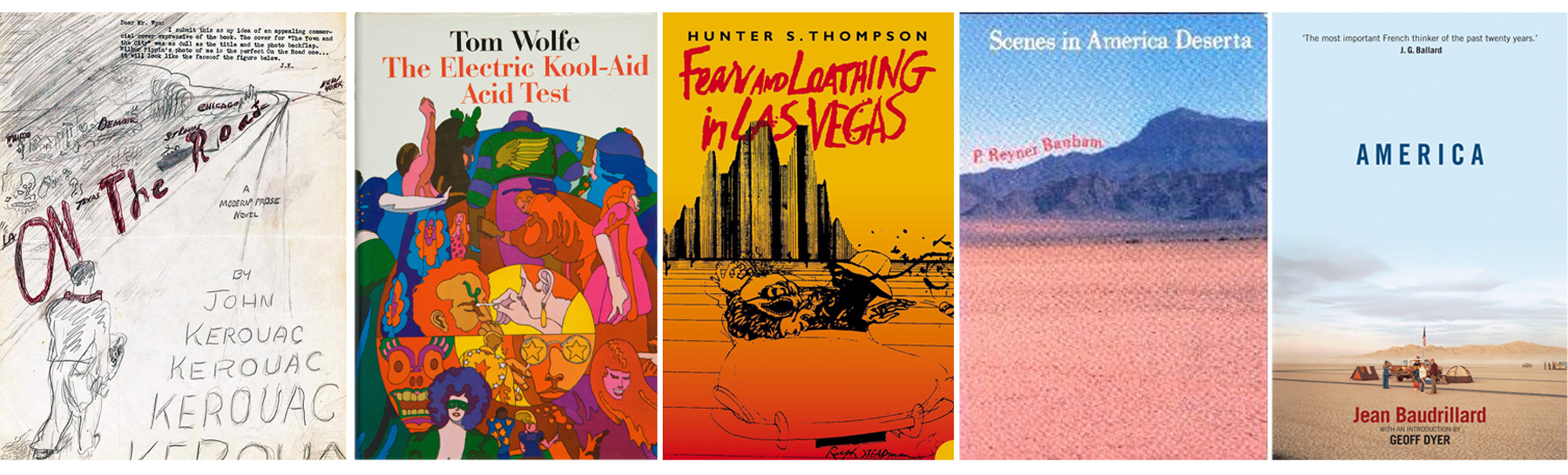

Travel soon became about the trip itself—a state of mind and lifestyle neither here nor there, legitimized by exception. America is the emblematic site for such gonzo-surveys of the end of the millennia. To throw off normalcy and search for something more real, a veritable population of restless youth set out in every direction, glimpsed through the semi-fictional, stream-of-consciousness literature by Jack Kerouac and a generation of postmodern writers.

On The Road begins in Paterson, New York where Sal Paradise meets Dean Moriarty. In three feverish weeks in his Manhattan apartment on West 20th Street, Kerouac narrated their escapades through Hollywood—Chicago—Denver—San Francisco—Mexico City and beyond; indelible visions of interstitial sub-urban landscapes. An interchangeable, infinite array of highway stops, gas stations and motel rooms.

Between Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and The Electric Kool Aid Test, authors Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe embellished the road trip genre with recreational drug use that produced a vivid, hysteric transcendence. Like a frontier allegory, Raoul Duke and Kesey’s Merry Pranksters conducted their savage, madcap excursions out West on the threshold of urbanity and reason: zooming across the Sonora desert to plunge into Las Vegas and all its artifice: boulevards, Bellagio, (Neon) Boneyard; from Perry Lane to La Honda to the cities.

These texts each depicted a disparate community, young and poor and wild, caught in a spasmodic exodus. Sal Paradise travelled alongside hitchhikers as lost as him, whereas The Merry Pranksters travelled on one lurid, beat-up schoolbus, each accessing remote psychological regions through ritualized substance abuse and increasingly toxic group dynamics. Who arrived anywhere? Post-idealistic journeys led to ennui and anticlimax.

These characters became alien to the communities and places they considered pathologically normal. This bewildered sense of dispossession is most pronounced and relished by the Europeans who came as retroactive historians of the New World’s miraculous modernity. Both Reyner Banham and Jean Baudrillard express morbid delight in their Los Angeles: An Architecture of Four Ecologies and America; Baudrillard pronounced it ‘utopia achieved’—'ou’ not, ‘topos’ place—a land so traversed to the point of dissolution.

END THOUGHTS

We have arrived at our present state from such historical trajectories. After all the true site of travel is a person’s singular internal reality. Having established the horizon, our sight might now return to the shores from which we gaze outward. Sedentary civilization is perhaps being superseded by nomadic patterns of a global, non-geographic form. This new tribe inhabits the states of limbo or ‘away’ in its various nuances. Their alternative lifestyles that fit in one suitcase on wheels produce a new kind of society, native to this liminal territory. Fleeting intersections take place in any city at any time, determined and documented in virtual space ad infinitum. Escapism is habitual and penciled into the agenda. Which points us towards the new plight of dwelling: refugees and jet set alike are caught in such a precarious dance, at home only for the hour or week, resting their heads against a window out onto the ceaselessly changing here.

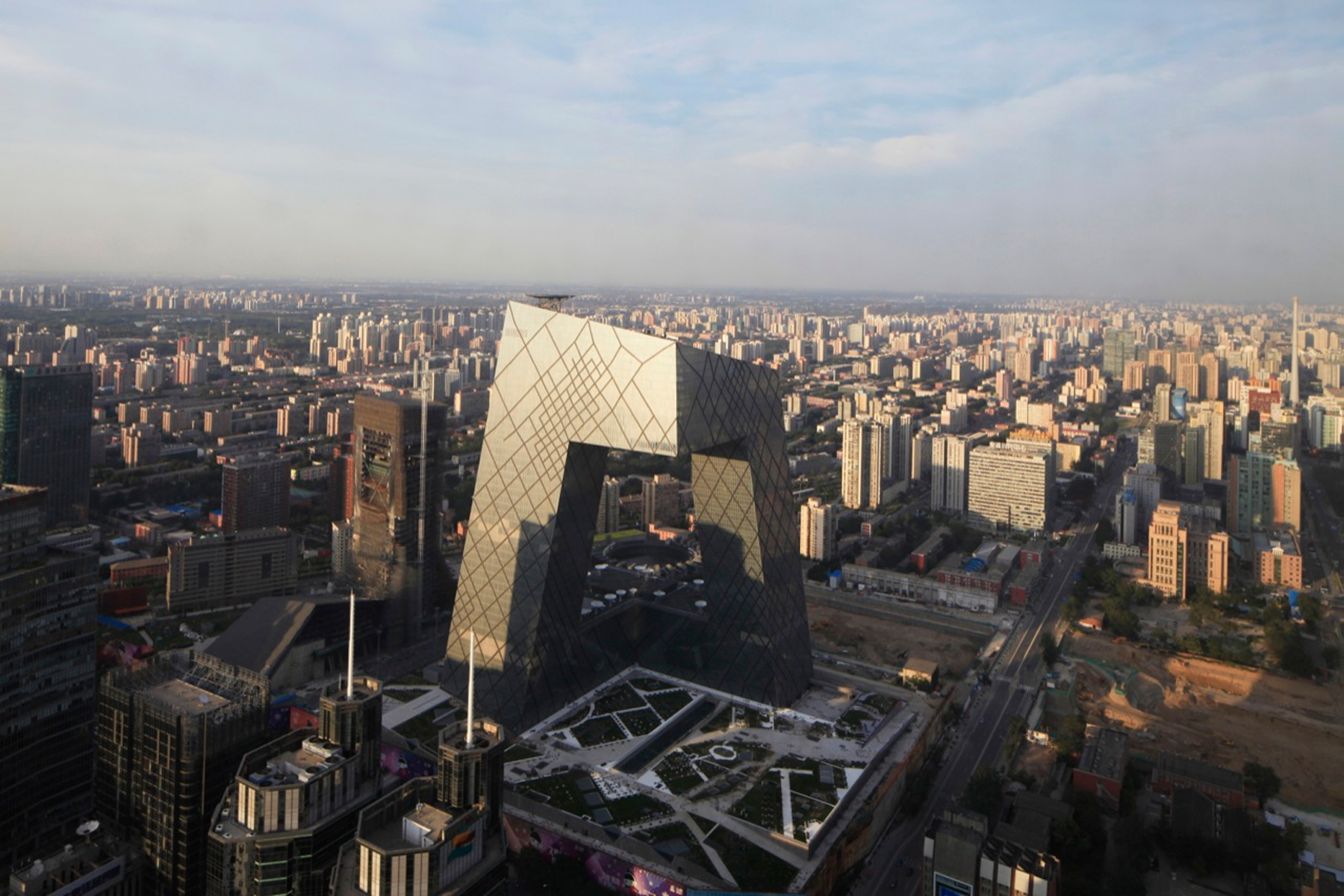

Being on the move produces a fitness and rigor in one’s faculties, as one exercises curiosity to look intently into the world seeking difference over familiarity with a measured naïveté. Our habits and discourse are changing to becoming increasingly relativistic and perhaps fragmented. Such cultural shifts should produce a new world order on the scale of systems and frameworks; while obsolete ones are waiting to be overthrown. By that word, travelers are the visionaries that might define the world of the future. The world beyond might have once been glimpsed through postcards and letters, but now appears in technicolor before us in an instant. It follows that en masse, travelers form a substantial intervening force in the urban landscape. It is through tourism that states are incentivized to emphasize and support local culture.

Furthermore this traffic gives rise to a third kind of landscape of the global generic; no-man’s lands between customs and boarding, duty free and outside of time, a parallel universe that mimics our neighbourhoods and cities with a sterile, abstract universality that is inexplicably comforting. The frequent traveler is often an unwittingly potent agent that realizes his influence too late. We see now that it is impossible to extricate sites such as Italy and California from these writers’ inscriptions.

So much for the innocence from which each bildungsroman sets out, for we come to this admission: that even the sands of the deserts are marked by our prodigal traces, and it is the destiny of territories to be cultivated by strangers.