Umbra

by Alexa Yong

Umbra

by Alexa Yong

In photography, finding the balance between highlights and shadows is crucial to ensure that the subject matter is illuminated in the best possible way. Rarely noticed, the shadow is one of life's constants and plays a vital role in the latest work of Dutch photographer Vivianne Sassen, whose extensive portfolio includes work for clients such as Acne Studios, 3.1 Phillip Lim and Carven.

At first glance, the subject matter appears straightforward and simple. Rothko-like colour studies in the desert, mirrors, body parts and silhouettes. They may seem unassuming—how exactly does one create art out of the ordinary? In Sassen's case, her intuition leads her to create a unique language, pushing her to invent new ways of looking at form. Characteristic of Sassen’s imagery is the way she draws the viewer’s attention to form, colour and composition. Her models take on body-bending poses, contrasting colours and cleverly positioned mirrors allow her to play with two and three-dimensionality. Shadows obscure the human form to create amorphous shapes that capture the imagination.

Like many of Sassen’s works, her new exhibition Umbra possesses a sort of visceral intelligence that is vastly greater than the sum of its parts. Commissioned by the Nederlands Fotomusuem in Rotterdam, the exhibition consists of six bodies of work—Axiom, Totem, Larvae, Carbon, Rebus and Soil—each of them exploring the connections between reality and abstraction through Sassen's signature treatment. London based curator and art writer Hansi Momodu-Gordon speaks to Sassen and unpacks the influences behind her award winning series, Umbra.

HMG: Last year your body of work Umbra was shown as a multi-part exhibition of still and moving images, with light projections and mirrors, and accompanied by a publication with poetry. Can you start by describing your inspiration for that project and how it came into being?

VS: The Netherlands Photo Museum in Rotterdam mentioned to me that they wanted to give me the assignment, supported by a collector, and actually it was kind of carte blanche. They told me I was completely free to do whatever I wanted to do, but they were interested in me doing something new, something unexpected, or at least something that would bring me out of my comfort zone.

It was also an opportunity to reflect on what you had previously done, and to do something new. At what point did you fixate on the idea of exploring the shadow—the title of the show means shadow, right?

Yes, Umbra means shadow in Latin. When they gave me this commission, I thought, well, I cannot do something completely new; it has to be somehow linked to my previous work. And I decided to investigate the shadow because the shadow has always been a very important part of my work. I was always wondering why... I thought there must be something there, a reason why I am so intrigued by the shadow. I think it’s partly because the shadow is about a kind of disclosure, or not revealing a very important part of something. That has always fascinated me, the things that you can’t see, the things that you can’t grasp.

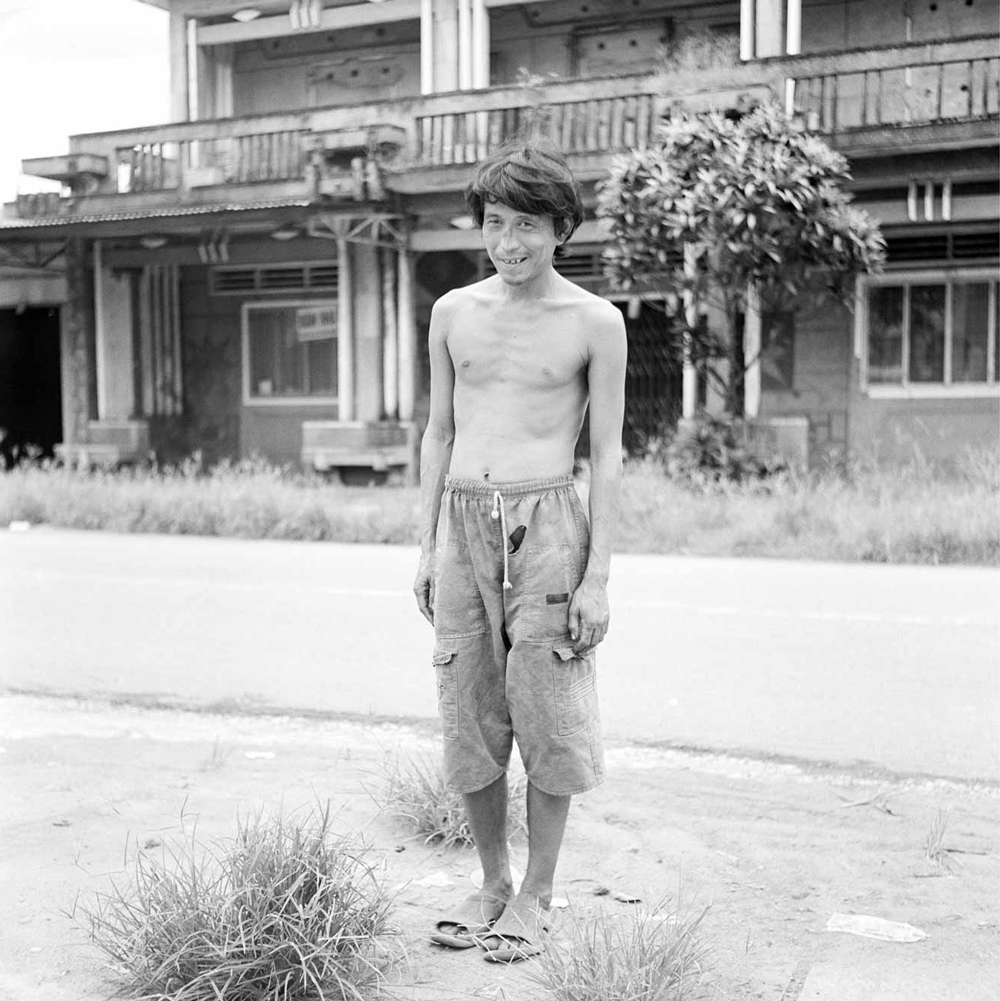

Silver Dollar, Larvae (2014).

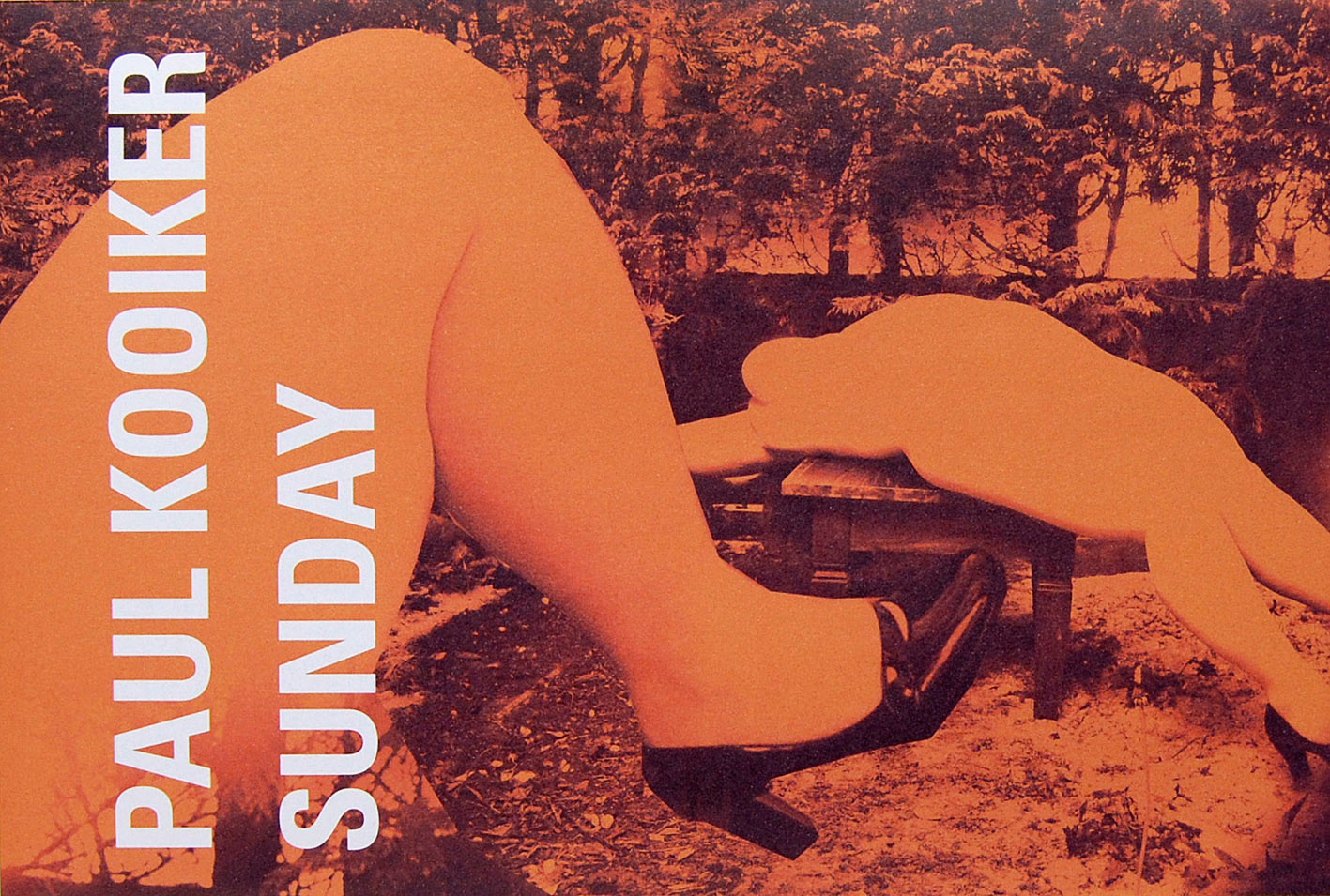

Axiom R03 (2014).

At first it was irritating because I started seeing shadows everywhere; it became very obvious in a way, you know, and very literal, which was not the idea. And so I thought, I have to do something else in order to get into this realm and make new work on a more conscious level—because I had always used the shadow on a very subconscious level. I started reading a lot about the shadow, for instance Victor Stoichita’s A Short History of the Shadow, which is about the shadow in art history, and there were some really amazing stories in that book which I used later. But, it all became a bit too academic for me. I’m not an academic or intellectual in that sense, or an artist who works in a very conceptual way. At that point, I thought, well, the only way to truly investigate these shadows is to go within, to investigate my own shadows. I needed someone to help me because there was this gap between my thoughts and the images that I wanted to make. I decided to contact a friend of mine who is a writer and poet, Maria Barnas; who is also an artist. At that time she lived in Berlin, so we started this email conversation and I asked her to write some poems about the shadow. We had previously worked on some books together, and she had written about my work in a very poetic way.

"I’m always interested in the incidental, and so all of a sudden when you have things moving, light moving, and also yourself as an object taking part or becoming a part of this installation, a lot of unexpected things happen."Vivanne Sassen

So did she write the poetry before you created the images?

Some of them, yes, and with some I sent her the work first, because I also went into my archive looking for images which contained shadows in a literal but also a personal, intimate or emotional way. So I sent those to her, but at that point I also started writing to her about my personal shadows, my fears and longings, fantasies, my memories and... well, basically everything that reminded me of shadows somehow.

She took that material, my letters to her, and combined those texts with her own personal shadows. And so those poems are a mix of the two.

Was that the first time you had gone back into your own archive to reflect and create new work?

Yes, yes it was.

And how did your reassessment of those previous works inform the new photography that you made for the project?

That’s a good question. I think at some point I decided that there were numerous interpretations of shadows in my work. For instance, there was this body of work I made when I was very young, still in art school, in 96 or 97, and those were images that translated back to the idea of the Jungian shadow, which Carl Jung describes in his archetypes as that part of our personality that we are afraid or ashamed of, also combining the sexual aspect of lust and the body.

Back then, I did a lot of pictures of nudes and self-portraits. and I was still exploring my own sexuality and having my first relationships... So that was something I thought could have a place within the show, as a separate chapter. Afterwards I took some more pictures to complement that story.

Could you talk a little bit about what the experience was like within the installation, and some of the relationships you set up between the images and works in the space?

Yes, I’ll guide you through it. The museum in Rotterdam is in a very large industrial building, and they divided it into seven different spaces. When you walked in you entered a space with a Beamer installation, with a large mirror on one side, a large wall, and then on another side there was a projection of still images that were moving past horizontally. There were a lot of landscapes, so you had the feeling that you were almost in the landscape and images emerged from the line. The mirror was not opposite, but at a 90-degree angle from the installation.

Once you entered this room you became part of this installation yourself, so you would cast a shadow on the wall and would also see your own projection.

The installation format feels like a natural extension of the way in which you compose your images—there seems to be a conscious interaction between space and figure, sculpture and form, which can be played with. In the installation the viewer becomes the protagonist on a set of your devising, they walk around, and they cast shadows. What was your experience of creating shadows for the installation? Did you envisage it in the same way you might a photographic shoot or set?

I wouldn’t compare it to an actual photo set, but on the other hand, now that you’re saying it, maybe it is. I’m always interested in the incidental, and so all of a sudden when you have things moving, light moving, and also yourself as an object taking part or becoming a part of this installation, a lot of unexpected things happen. I think photography is quite limited in the way you perceive or view it, whereas with an installation like this it’s more of an experience. I found this very interesting to discover. I even made this kind of soundscape in collaboration with someone as part of this experience that you could enter and walk around in.

You first published Umbra as a folder of prints and a booklet of poems, and you’ve just made a second version of the book that was designed by Irma Boom. What was your experience of thinking through the sequencing of the images the second time around?

The second time around I thought it shouldn’t be so literal. In the exhibition, the installation which we were just talking about, Totem, is one of several installations within the show; others contain different set-ups and different work. So I thought it would be more interesting to mix the images up a bit instead of making them into separate chapters.

I think the first publication is much more about the poems than about the images. In the second publication it’s the other way around, the poems are a bit hidden because they are in folded paper, so you can read them and you can see them, but it’s a bit harder. There are still these different chapters, but they run through the whole book. You can kind of feel them by the way the book was designed and the paper that was used—some pictures are on matte paper and others on glossy paper, including the larger series which comes back several times within the book.

This is an extract from an interview published in 9 Weeks, a book of interviews and essays with Stevenson gallery artists by Hansi Momodu-Gordon.

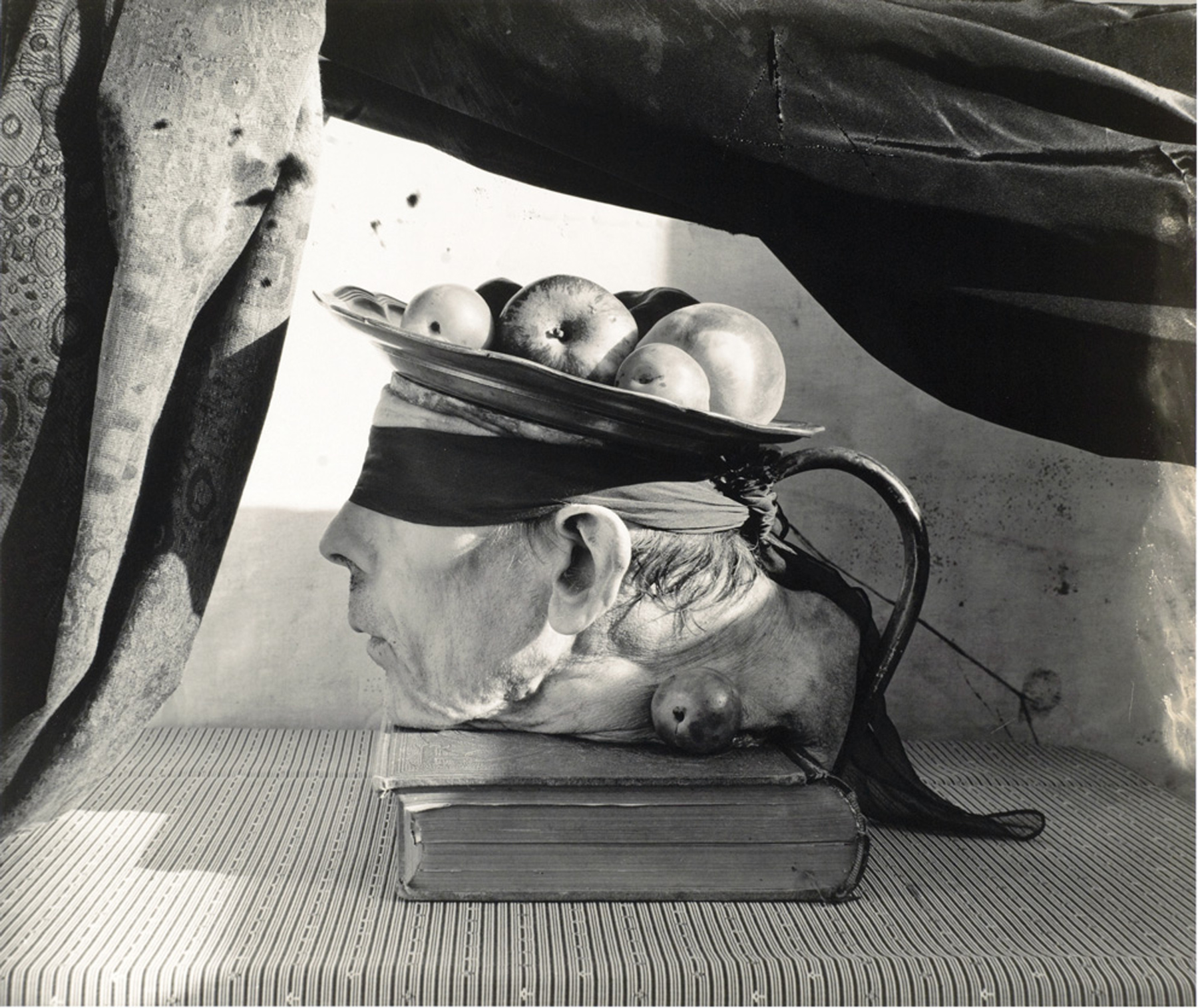

Mirte, Totem (2014).

Heine #02, Totem (2014).