In the Shadows

of Chineseness

Interview by Grace Hong

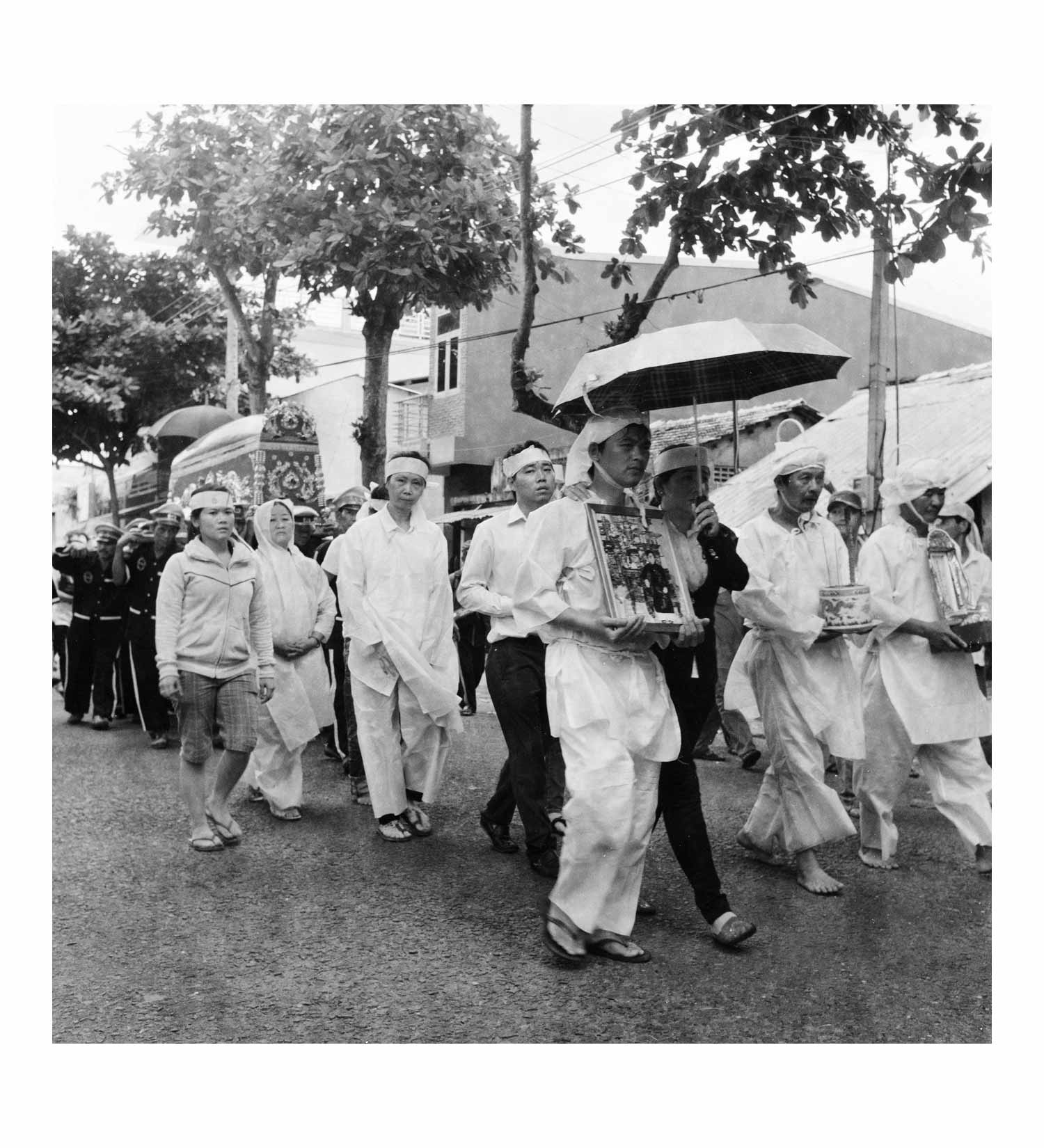

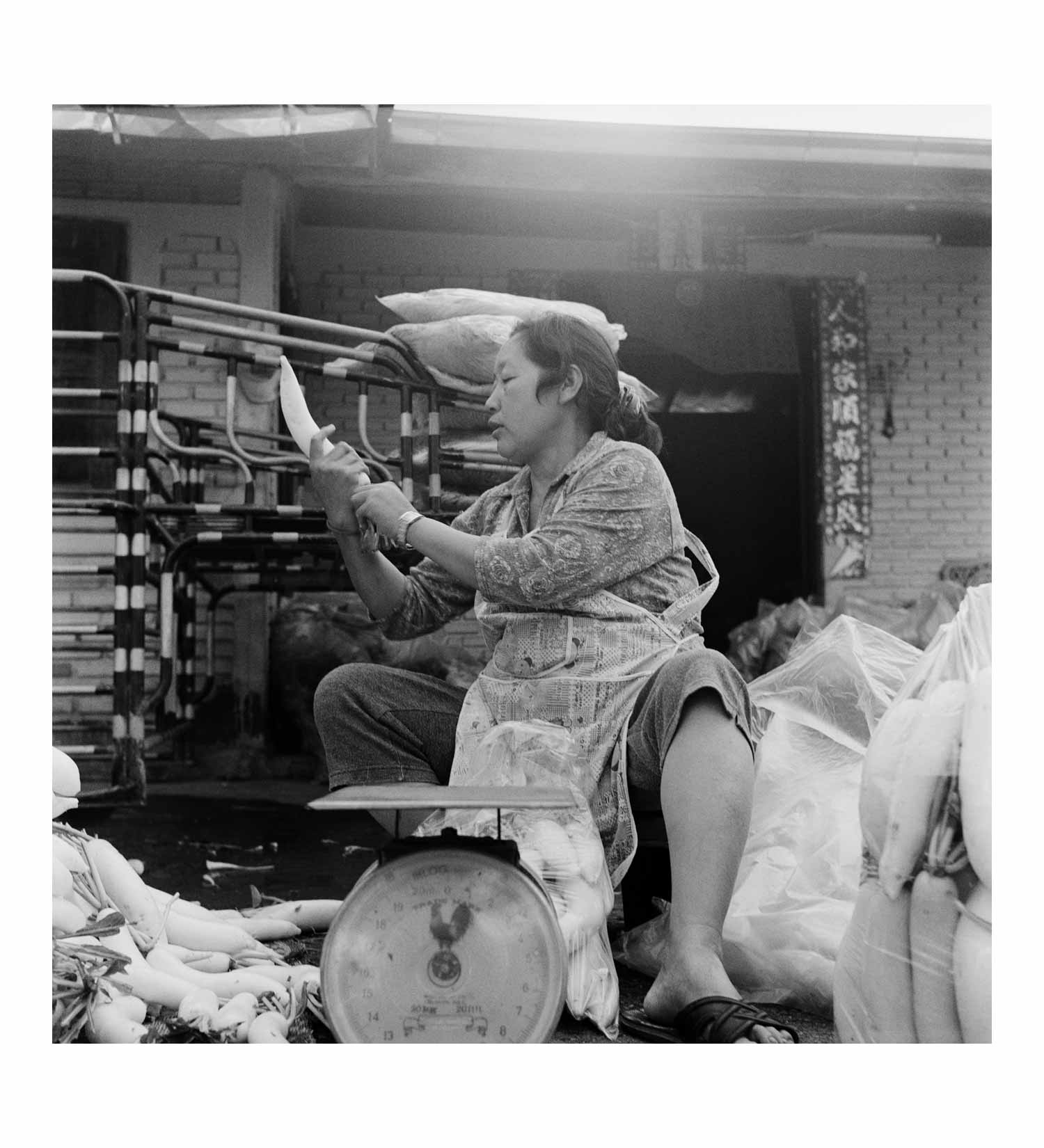

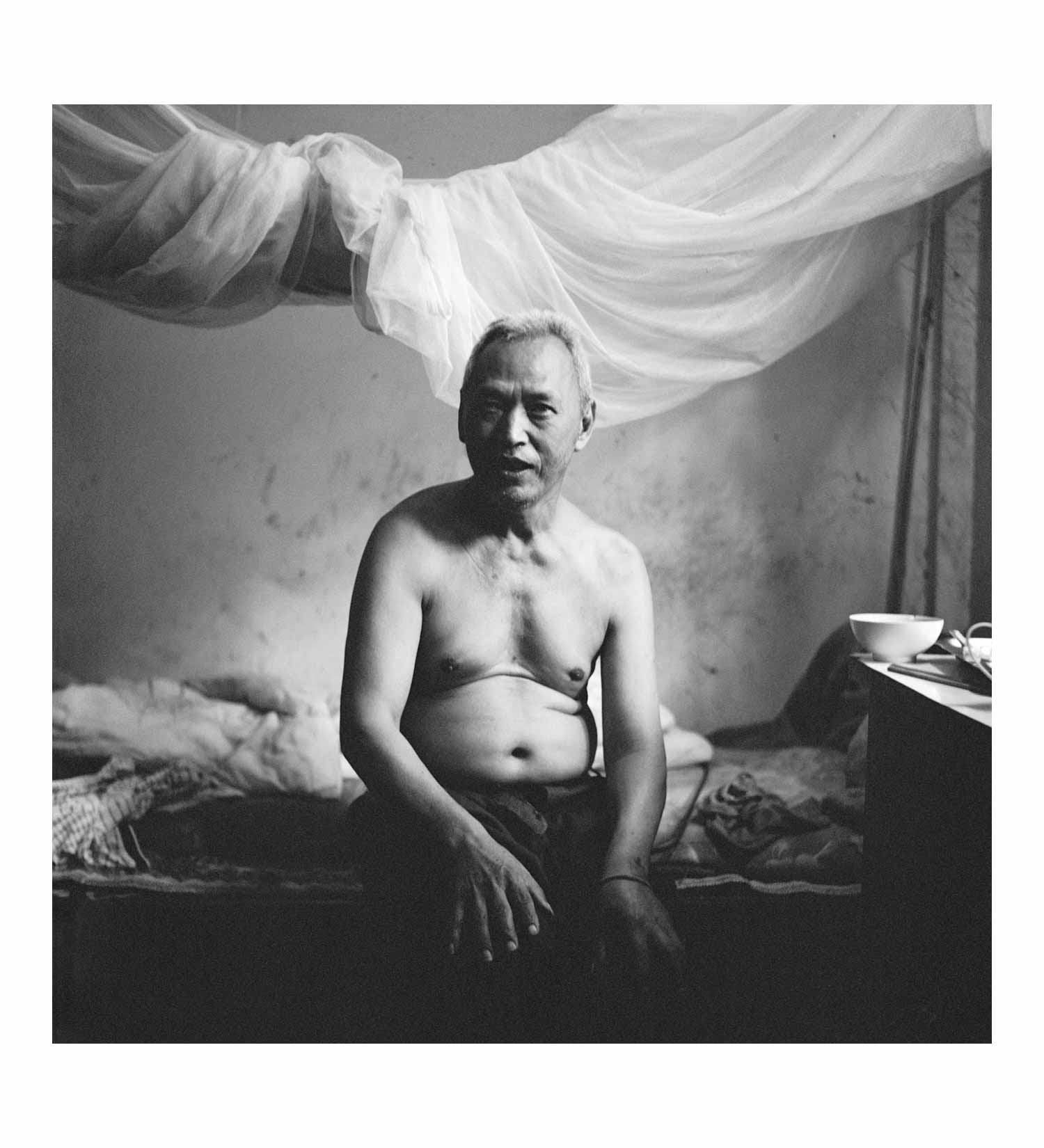

Photography by Zhuang Wubin

of Chineseness

Interview by Grace Hong

Photography by Zhuang Wubin

For many digital natives, the immediate solution to making things old is a turn to the black-and-white filter. Grainy, low-resolution footage with rough cuts set to whimsical music is the style du jour—from the casual Instagram user eager to generate memorabilia of trips overseas, to Kylie Jenner’s announcement of her daughter. By rendering high resolution images old and pixelated, a sense of authenticity is added; making the images seem more real when scrolling through a sea of the same. Consumers today purchase the latest in technology only to strive for an aesthetic of the past. In particular, the black-and-white photograph lends the easy familiarity of something from the archives. If something is stripped of colour, the assumption is that it must be old, and even valuable.

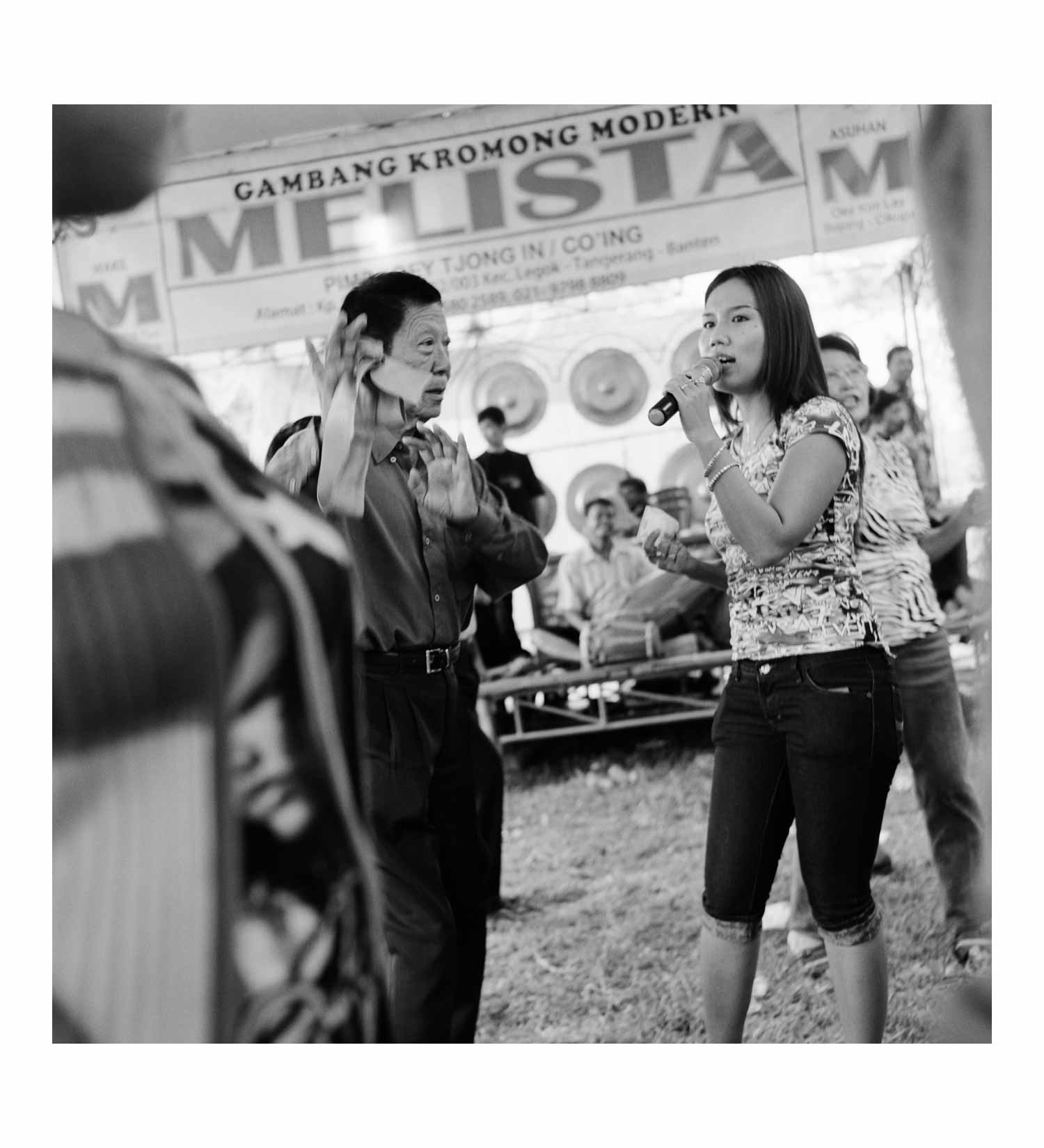

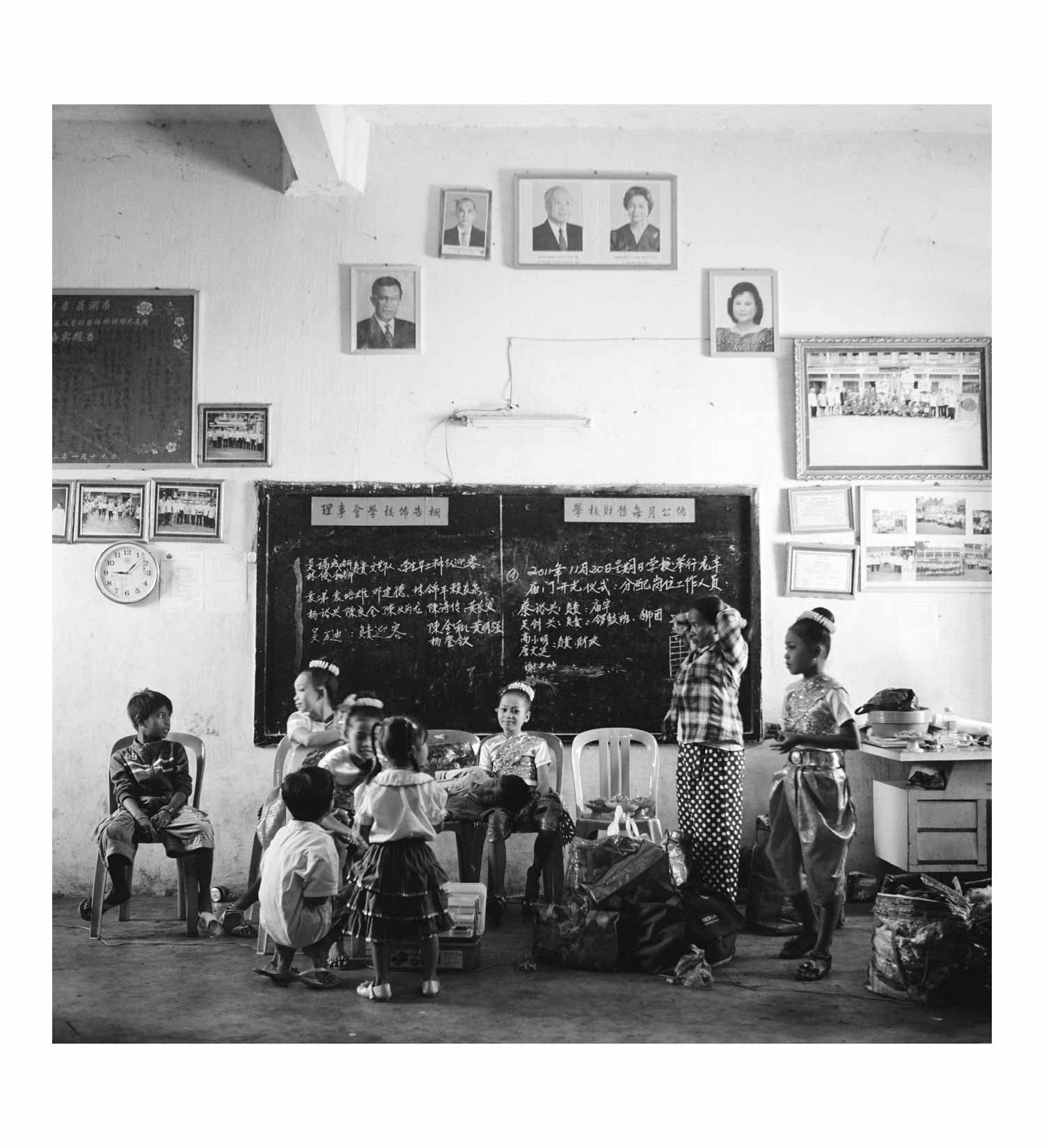

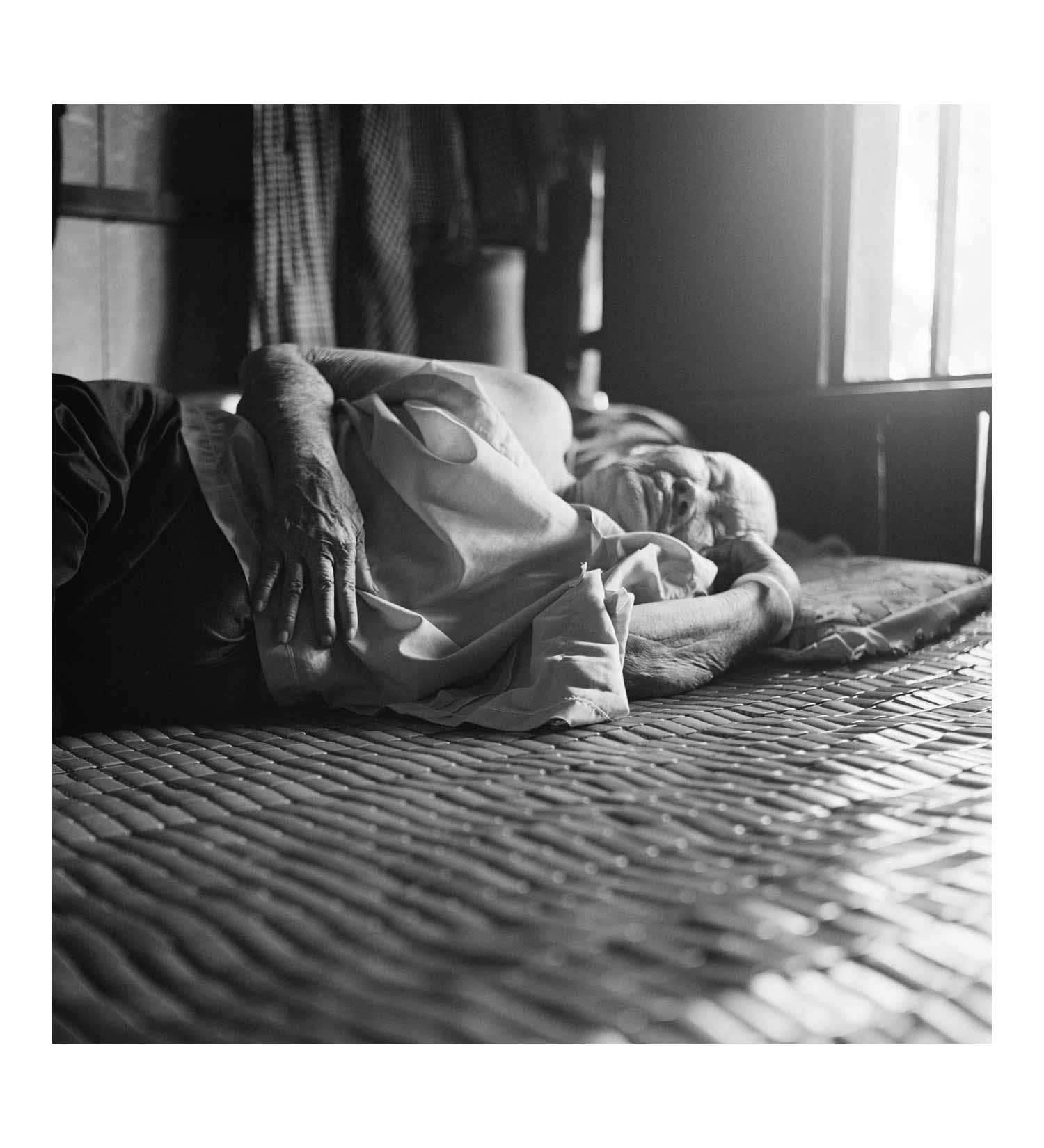

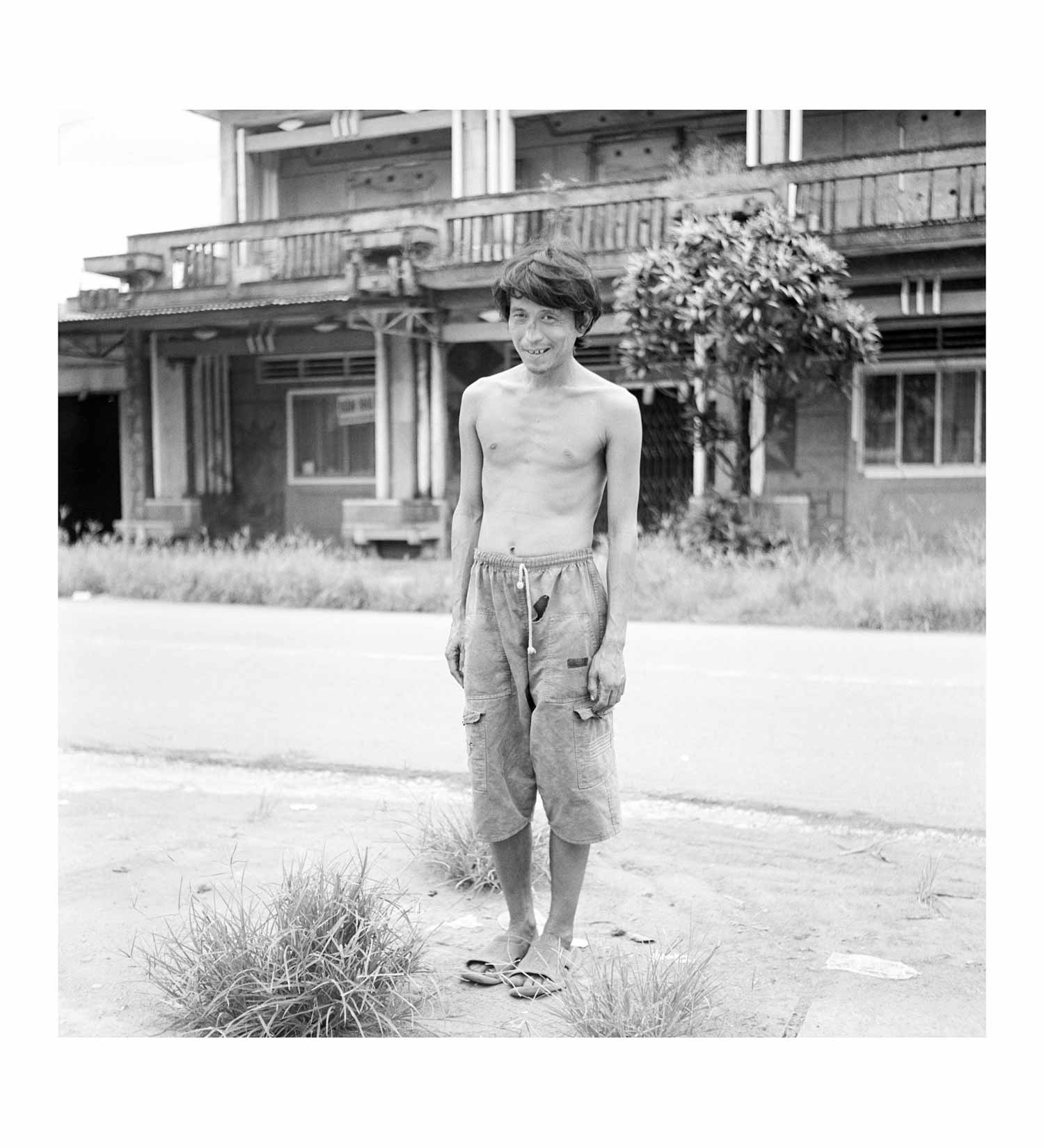

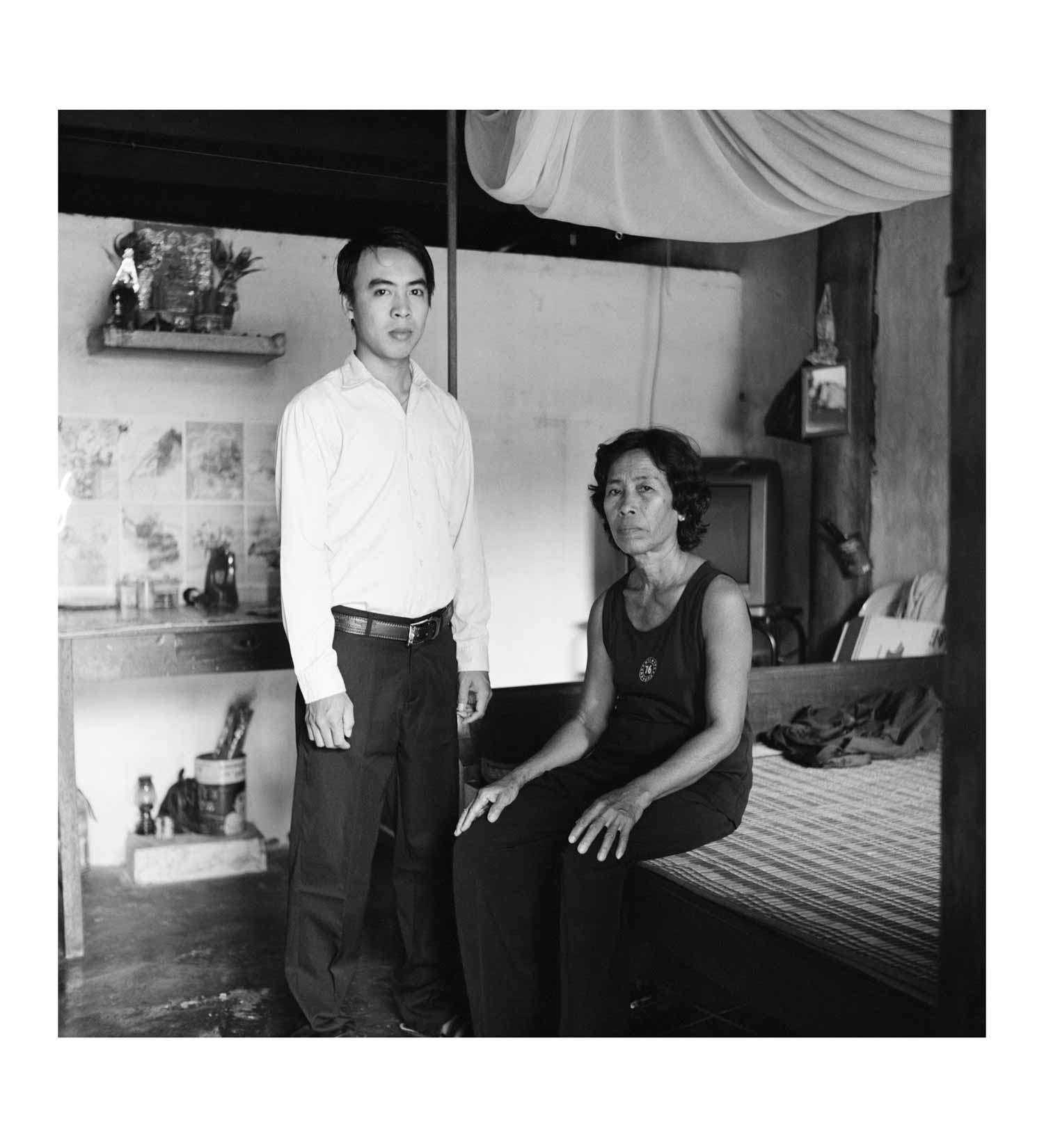

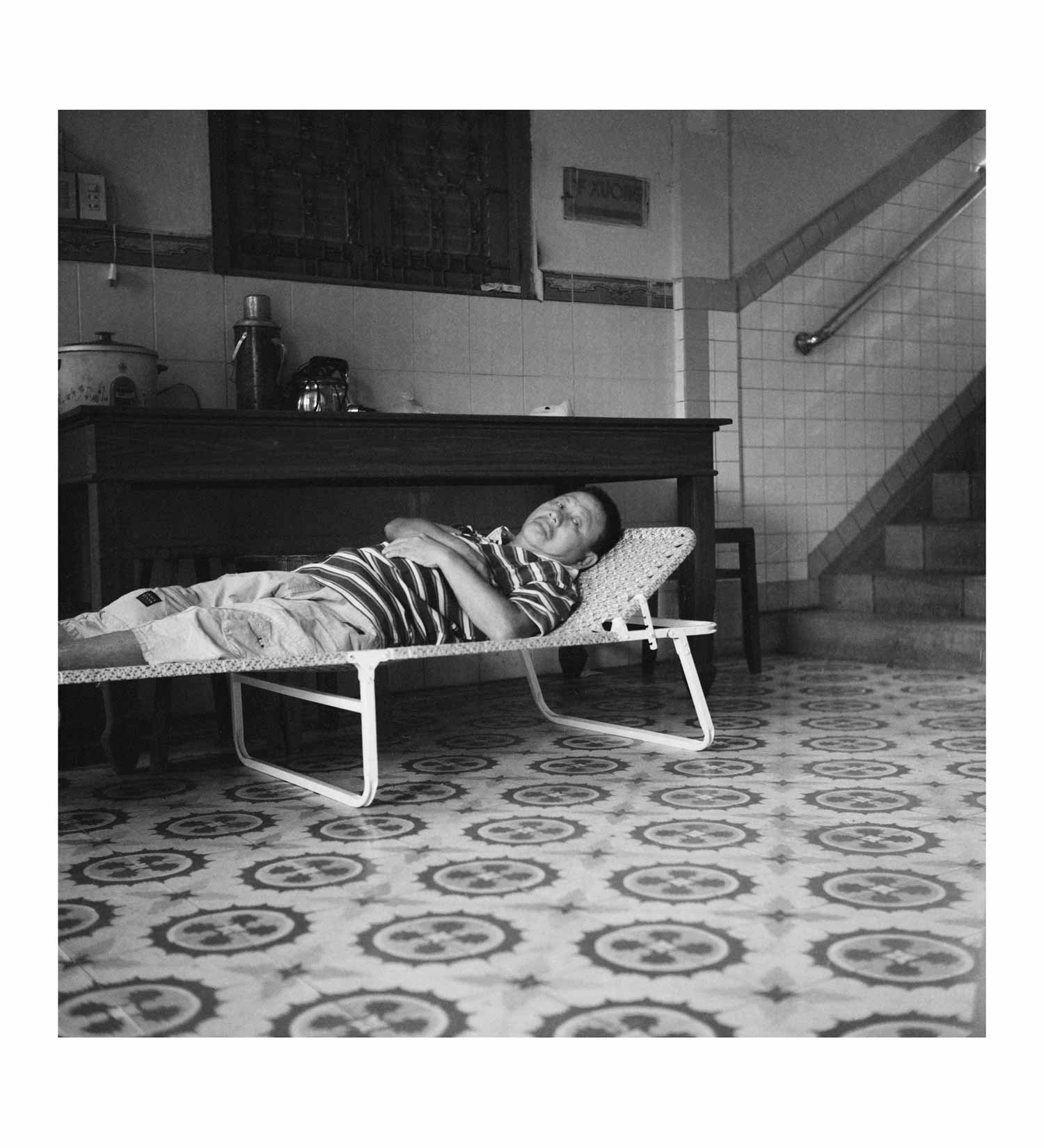

For Zhuang Wubin, perhaps this conceit works in his favour—the black and white photograph cues us to the historicising nature of his work. A writer, curator, educator and artist, Zhuang uses photography and text to visualise the longstanding 'Chinese' communities in Southeast Asia. Beginning in 2010, 小城故事 | Small-Town Stories: Living in the Shadows of Chineseness is an art project that features, at this stage, limited-edition black and white prints, field notes, as well as a box of photographs (made by Zhuang or purchased at different flea markets across the region) and artefacts which he affectionately refers to as a “portable museum”. At first glance, his body of work seems pulled from the archives; photographs of people captured in their everyday lives, telling stories of their pasts. However, it is very much contemporary photography taken in recent years.

Small-Town Stories writes the unwritten histories of the rural and semi-urban Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Taking a cue from political scientist Mary Somers Heidhues’ investigation of the relationship between legitimacy and belonging, Small-Town Stories is borne of Zhuang’s interest in Chinese communities found in semi-rural towns and locales in the countryside. The first settlers arrived at these places as political refugees, indentured labour, and even mercenaries. Through the passage of time, these communities formed traditions, and cultures unique only to them, different from their past and present landscape. Reading his work, the understanding of identity—Chinese-ness in particular—becomes fluid, contingent on the here and now.

"Nostalgia doesn't help us in anything. It just blocks us from understanding the actual situation. In some way, this kind of work is to a certain scientific degree but there is a lot of fictional aspects to it."Zhuang Wubin

Previously, you have published a photobook titled Chinese Muslims in Indonesia (2011) while this current project is centers on small towns and rural areas of Southeast Asia. How did you arrive here?

For this work, the starting point was actually Mary Somers Heidhues’ paper that was published some 20 years back, in which she talked about the lack of research on the Chinese in rural areas. If you look at the general account of Chinese migration in Southeast Asia, typically it focuses on success stories, the usual rags-to-riches narrative.

For Singapore, it’s part of the national narrative for the new generation.

The rags-to-riches narrative is also fairly common in Southeast Asia. Heidhues’ point is that there is an over-emphasis on the successful Chinese who live in the major cities of the region. However, there are of course sizable Chinese communities in semi-rural areas, for instance, who are agriculturalists or small-time businessmen. The profile of the Chinese communities in Southeast Asia is obviously not so homogenous. Furthermore, in the major cities, there’s usually a lot of pressure to destroy and rebuild, so it is a little bit more difficult to visualise the Chinese experiences of the past. But if you visit the semi-urban spaces where the pace of development is slower, it is a bit easier to visualise the way things used to be, simply because there are still, old houses standing.

Is nostalgia a reason why you were attracted to it?

No, because I’m not interested in nostalgia. Nostalgia doesn’t help us in anything. It just blocks us from thinking about the reasons behind a certain phenomenon. In a way, my work is somewhat scientific but there are a lot of imaginative elements to it.

What do you mean by that?

Because there are certain things we are not overly sure of. And within a family itself, there is a lot of new thinking, such as where did my ancestors come from? It then links to greater ancestors from somewhere else.

Going back to the small towns that you visited, can you tell us more about where you went?

The reason why I picked specific places to visit often has to do with what has been studied previously in terms of research. If you look at the wedding photograph, it took place at Tangerang (丹格朗), West Java, in the cina benteng (Chinese of the fort) community. Thus far, I have also visited the communities in the Mekong Delta, the bordering regions between Northern Thailand and Myanmar, south central Laos, Sabah in East Malaysia and Kampot, Cambodia. I use published research as a guide, so that I don’t have to start from scratch. However, I have also visited places that my friends across Southeast Asia have recommended, including Parakan in Central Java.

Who are these people? How did they get there?

The migratory experiences of the Chinese to the region of Southeast Asia are really varied. It is difficult to characterise in a simplistic way. Very often, the migratory experiences of our forefathers were quite contingent and not always within their control. For instance, I would have been born in the Philippines if my paternal grandfather got his way and ended up in Manila. The war forced him to go south towards Malaya.

Can you tell us more about the people in the pictures?

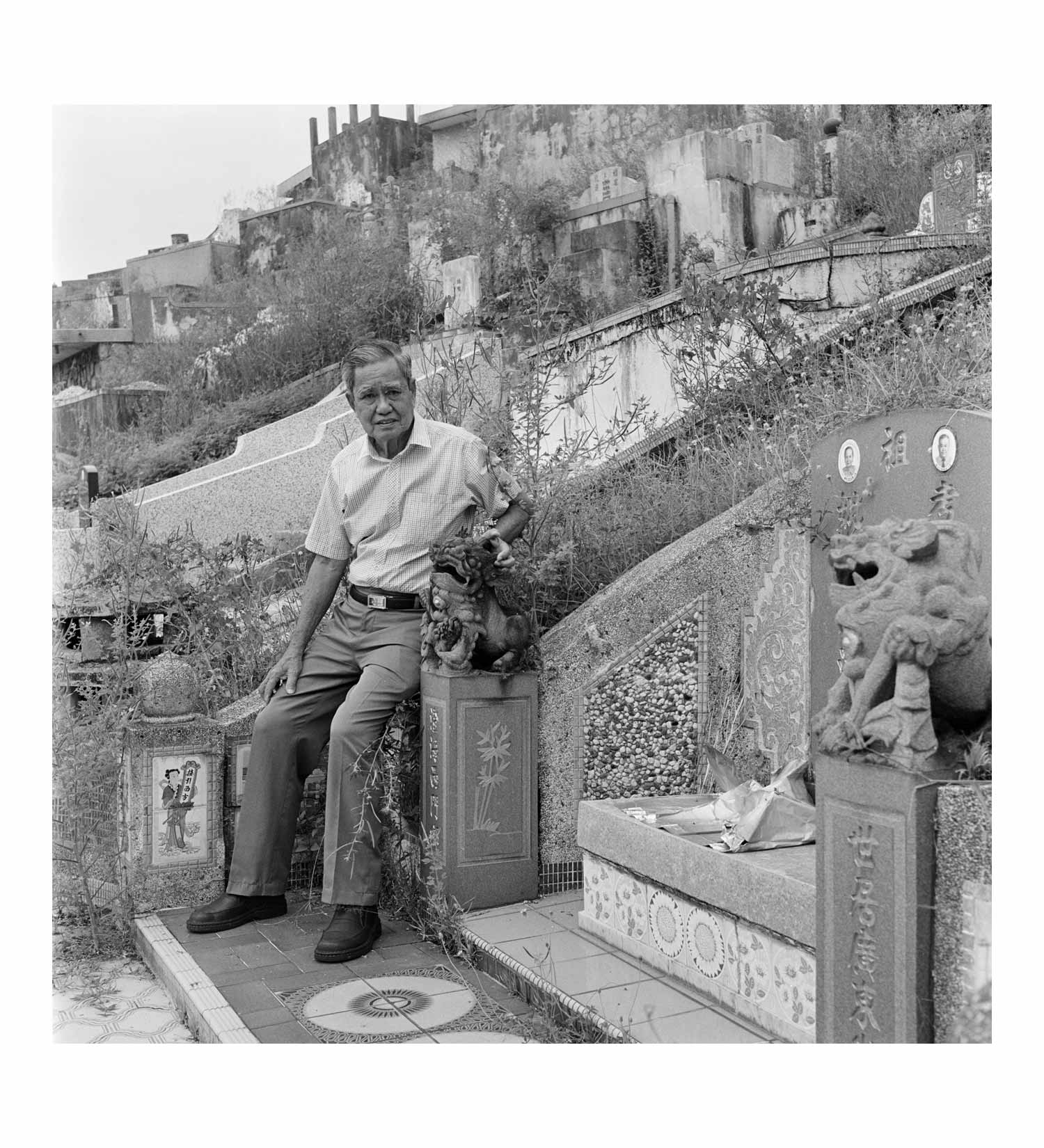

The image that you see of the pots and the photograph of the cemetery, they were shot in Chang Mai Province, Northern Thailand, bordering Myanmar. These are Yunnanese migrants, many of them former Kuomintang (KMT) soldiers who fought the civil war in China. When the Chinese Communist Party won in 1949, the Yunnanese soldiers flocked into Northern Burma, where they set up camp. Eventually, some of them were evicted to Thailand. For many decades, Thai and Burmese authorities could not extend complete control to the bordering regions between Thailand and Burma. When the KMT soldiers arrived, they brought their families as well. As communism took hold in China, there were also Yunnanese people involved in small businesses and trade who left because of fear and retaliation. Some of them would also end up in Thailand.

The image of the tomb, for instance, is taken in Chaiprakarn District, Chiang Mai Province. The Yunnanese villagers told me that even in the 1980s, people would not be able to enter this area so easily. There were Yunnanese soldiers guarding the entry and access of this area.

What do these families do?

Some of them are involved in the opium trade. Others are involved in farming. Interestingly, during the 1970s, with the Thai military struggling to control the communists in Thailand, they mobilised these KMT soldiers to fight for the government. In recognition of their contribution to Thailand, many of these KMT soldiers have since been given citizenship.

Looking at the grave, it looks like a wedding knot.

I am not sure why there is a knot. I’m still trying to find the reason for that. Whenever I visit a new site, one of the first places I usually head to is the cemetery. This is because the cemetery can provide us a lot of historical information that even the nearby residents might not be able to offer, especially in places where only a few Chinese families remain and that there is very little documentation left. For instance, I visited the rural areas of Sumenep Regency on Madura Island, which is located off East Java. In the country roads, you would sometimes encounter a Chinese family at a T-junction. Sometimes, you would find a few houses that display Dutch and Chinese influences. These places are already quite far from Surabaya, the major city in East Java. There are no temples in these places and you would not be able to find documentation in this way. For the one or two Chinese families that remain, they typically operate a small shop selling different things. Others have already moved to the city of Sumenep or Surabaya.

Do they wonder why you want to take photos of them?

They are mostly open towards me. I guess they don’t really think about it. Some are naturally embarrassed, but I would be embarrassed too if somebody were to take a picture of me. In most cases, they are very welcoming.

Take this photograph of a Muslim in hijab; she lives at a cross junction of the country roads in Sumenep Regency. Her ancestors left a house and some land. If you look behind her, the windows remind me of Chinese houses in other parts of Southeast Asia. I started this project without trying to answer the question of Chineseness. However, as I revisit this photograph over the years, I started thinking about the politics of my intervention. She lives in this quiet, isolated place. If I do not show up at her place, she would not need to perform her Chineseness for my camera. She would look like any other Indonesian with her hijab. In some ways, I wonder if I’m replicating a certain kind of violence because she might just want to be identified as an Indonesian. Today, she has no need for Chineseness in the place where she lives, distanced from the communal politics in Indonesia. However, because I’m there looking for Peranakans or local-born Chinese Indonesians, she has to surface that part of her biography for me. On the other hand, she does have an Indonesian name and a Chinese name. Neither did she shy away from my questions. In this project, I always work with consent. Near her house, there is a family cemetery for the Chinese people who lived in the vicinity of this road junction. There, you would find Buddhists buried next to Muslims and Christians. You would find Peranakans of all religious faiths buried in the tiny cemetery.

Are they from the same family?

I suppose they had become somewhat related due to intermarriages. They had different surnames. Some of them were Muslims, so their tombs display both their Islamic and Chinese names. As I started thinking about my “violence” as a photographer, I also realised that Chineseness can be a type of performance as well. In Singapore, because of acculturation or the fact that Chinese remain the majority, it seems that the issue of Chineseness is not relevant to us. However, in places where the Chinese remain the minority, the issue takes on a different urgency, like the Indonesian-Chinese who experience on a daily basis different mechanisms that remind them of their otherness. It is hard to generalise about Chineseness, which has an element of contingency to the idea. On the other hand, the term “diaspora” is problematic because it implies an inability to be home. I think a migrant should have the right, within certain conditions and beyond a specific time frame, to become local, or to be accepted as local. However, in some cases, they are not allowed to be home, even though they have been three or four generations removed from their places-of-origin.

Some of the photographs are quite staged as well, would you give them the opportunity to represent themselves as the way they would like to be presented?

There is a common assumption that straight photography is conceptually naive. There are others who assume that we can see through the politics of a photographer and the sitters in a photograph. That’s not true. I met a different family at another T-junction in Sumenep Regency. They own a small convenience store. When I asked to make a portrait of all three members of the family together, the wife replied, “No, it’s very pantang (Malay for bad luck) for three persons to appear in one photograph. You cannot do that.”

Oh, I think the superstition goes that the middle person will die.

The only way I could do it was to photograph the father and the wife first, and then make another photograph of the father and his son. Nevertheless, if I just present the photograph without explanation, you wouldn’t know the negotiation that had already taken place. Hence, even though we might think of ethnographic photography as record, in truth it is a product of the desires between the photographer and the sitters. It is never a naive product.

You shoot in black-and-white, what are the choices that made that switch?

This question is about the format. Yes, my previous photobook, Chinese Muslims in Indonesia, was shot in digital colour from 2007 to 2009. By the end of 2010, I was bored with digital photography. I also wanted to pay tribute to analogue photography. On a practical level, colour negative is more expensive than black-and-white film. I find it very interesting to situate my work in the context of the contemporary because it seems that the contemporary (especially digital culture) readily allows anachronistic elements to co-exist, as though there is no issue in that kind of juxtaposition.

I can’t help but feel a sense of nostalgia because of the black-and-white nature of the print. How does shooting in black-and-white go with your personal dislike towards nostalgia?

What I would like to stress is that even in the small-towns and rural areas, there are changes taking place. Part of the work is to record these changes. I don’t feel any kind of nostalgia partly because I never grew up in these places. In any case, nostalgia is a strange idea to me. I guess it helps to have a certain detachment to my work. In short, I’m very wary that the project might come across as an attempt to celebrate a vague, romantic past. When it is exhibited, I cannot prevent a visitor from having nostalgic feelings towards the work. The danger is when nostalgia becomes part of a constructed impetus to mythicise the past, to erase the lived experiences of these rural and semi-urban places in order to romanticise them. This is clearly problematic to me. When I say I wish to pay tribute to a particular photographic format, I’m talking more about the way of working—the camera used, the ways of making images. In digital photography, it is easy to fade the saturation to make images look nostalgic. That is not the logic of this work.

Your previous book about Chinese-Muslims in Indonesia has a very specific context to the different elements. I was wondering what would be some comparisons between the two projects?

With every project that I do, I try to evolve my practice. My work on the Chinese Muslims was a personal attempt to figure out certain things. I wanted to do a project in Indonesia and I wanted to travel across the country. I decided to investigate a very specific topic. In a way, the photography is quite straightforward. This ongoing work about the encounters and reactions of Chineseness in small towns and semi-rural areas across Southeast Asia consists of different components, some of which are still being developed. Maybe it is a little bit too early to talk about my reflections. Nevertheless, I wish to briefly mention the box of artefacts that I have now incorporated into the work. This is where I have included the more imaginative aspects of this project, including short stories that I have written based on my fieldwork in Southeast Asia. They take the form of private letters that can be found in the different versions of the box installation. I have also included other materials that I have collected during fieldwork, such as name cards and wedding invites, nestling them amongst old family photographs that I have purchased in different flea markets across the region. In a way, the box is a self-contained “museum”, even though it actually references the way in which some people in the past would have kept precious objects and photographs related to the family. Here, I call it my “portable museum”.