For her Spring/ Summer 18 collection, London-based designer Grace Wales Bonner revisited one of her literary favourites, James Baldwin, the queer African American writer of the widely acclaimed Giovanni’s Room—a novel detailing a tortured homoerotic love affair between the American protagonist and an Italian bartender. Known for her cerebral approach to fashion, programme booklets filled with literary and artistic references explained the many inspirations that informed Wales Bonner’s response to male sexuality: an essay by Pulitzer Prize winning writer Hilton Als, pictures from The Homoerotic Portraits of Carl Van Vechten, and snippets from the notebook of little known writer Gary Fisher, among others. Drawing inspiration from various sources, a large part of Wales Bonner’s designs involves a masterful negotiation of the conceptual terrains between intellectual and creative boundaries. From tropes of identity to mediums of expression, Wales Bonner never skews towards a single idea for a collection. These high-brow and sometimes obscure references as read on paper can often appear intimidating to an audience incapable of pinning down her central focus at first glance. Yet, these disparate ideas elide beautifully when they meet in the in-between, finding relief in her immaculately constructed clothes.

At just 26, newcomer Grace Wales Bonner’s decorated vision of menswear has quietly set ripples off in the industry, sweeping major accolades with relatively muted fanfare when set against the frantic frenzy surrounding contemporaries like Demna Gvasalia and Alessandro Michele. Through her eponymous label, Wales Bonner has consistently navigated the intricate and overlapping realms of ethnicity, sexuality, and masculinity, taking particular interest in the black male figure. Within a short span of three years, she has achieved considerable success, winning the 2014 L’Oreal Professional Talent Award, the 2015 Emerging Menswear Designer under the British Fashion Awards, and the coveted 2016 LVMH Prize, bestowing credence that any newcomer could only dream of.

In some sense, Wales Bonner’s upbringing played an important part in inspiring her exploration of race and ethnicity. Growing up in South London, the middle of three daughters to a Jamaican father and an English mother, Wales Bonner’s mixed heritage places her within a complex gamut of inter-racial identity. With a pale, cream-like complexion, her appearance often befuddles those who mistakenly associate race with skin colour. In an interview with The Guardian’s Lauren Cochrane, Wales Bonner remarked that she “had some pressure to prove [her] blackness” while growing up. Being neither “ "black" enough to be black, "white" enough to be white, a consideration that in itself reflects the inadequacies of nomenclature in explaining ethnicity, her identity falls outside the Manichean conception of those who see the world in black and white. Being of mixed heritage in a world that till today can barely grapple with the sensitivities of race means struggling to reconcile her genealogy with the way the world perceives her. Drawing inspiration from artists, writers, and musicians who explore black identity, Wales Bonner’s collections can be seen in part as an intuitive response to this conflict, every seam and thread weaving a dense narrative that speaks of a quiet, resolute reclamation of black culture that has long been misappropriated and sidelined.

Acknowledging that her “identity lies between the two different cultures,” Wales Bonner navigates her liminality “exploring the space between European ideals... and something very... directly African”. Inspired by artists like Kerry James Marshall and musicians such as Chevalier de Saint-Georges, she inherits a tradition of working within an established European framework while deconstructing its formalised structures through the lens of black identity, exploring an aesthetic interstitial state by mixing Western couture techniques with African workmanship. Conceptually, she also draws from Western and African ideas: for her graduate collection, she was inspired by the filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles and the 1970s film genre Blaxploitation, exploring the Black Aesthetics Movement that marked a sharp pivoting in the development of black visual culture which targeted mainly black audiences. She took these radical ideas and melded them with the influence of Coco Chanel, creating clothes that recalled film characters such as Super Fly and Foxy Brown—long duster coats paired with high-waisted trousers reimagined in bouclé tweed with sweet, hushed tones, a material typically associated with Chanel’s jackets and coats.

In the process of tracing her Afro-Caribbean heritage, Wales Bonner began to root for a definition by acquiring a thoughtful, academic approach towards design, distilling ideas into heavily referenced collections accompanied with highbrow bibliographies of scholarly import. For her graduate collection, she voluntarily turned in a 10,000-word dissertation to supplement the collection. All of her collections have been accompanied with handouts that explain her inspirations, drawing a list of references that one would expect to find in an academic essay rather than a fashion show press release.

In her 2015 collection, "Ebonics", she referenced highly acclaimed gay black writers in her presentation like Langston Hughes (leading man of the Harlem Renaissance) as well as James Baldwin. Wales Bonner has also drawn inspiration from historical figures such as Malik Ambar and Haile Selassie—the former, a 17th-century Ethiopian slave-turned-Indian-ruler and the latter, an Ethiopian ruler who resisted Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia—distilling a trove of knowledge into reference heavy, yet poetically stylish clothes.

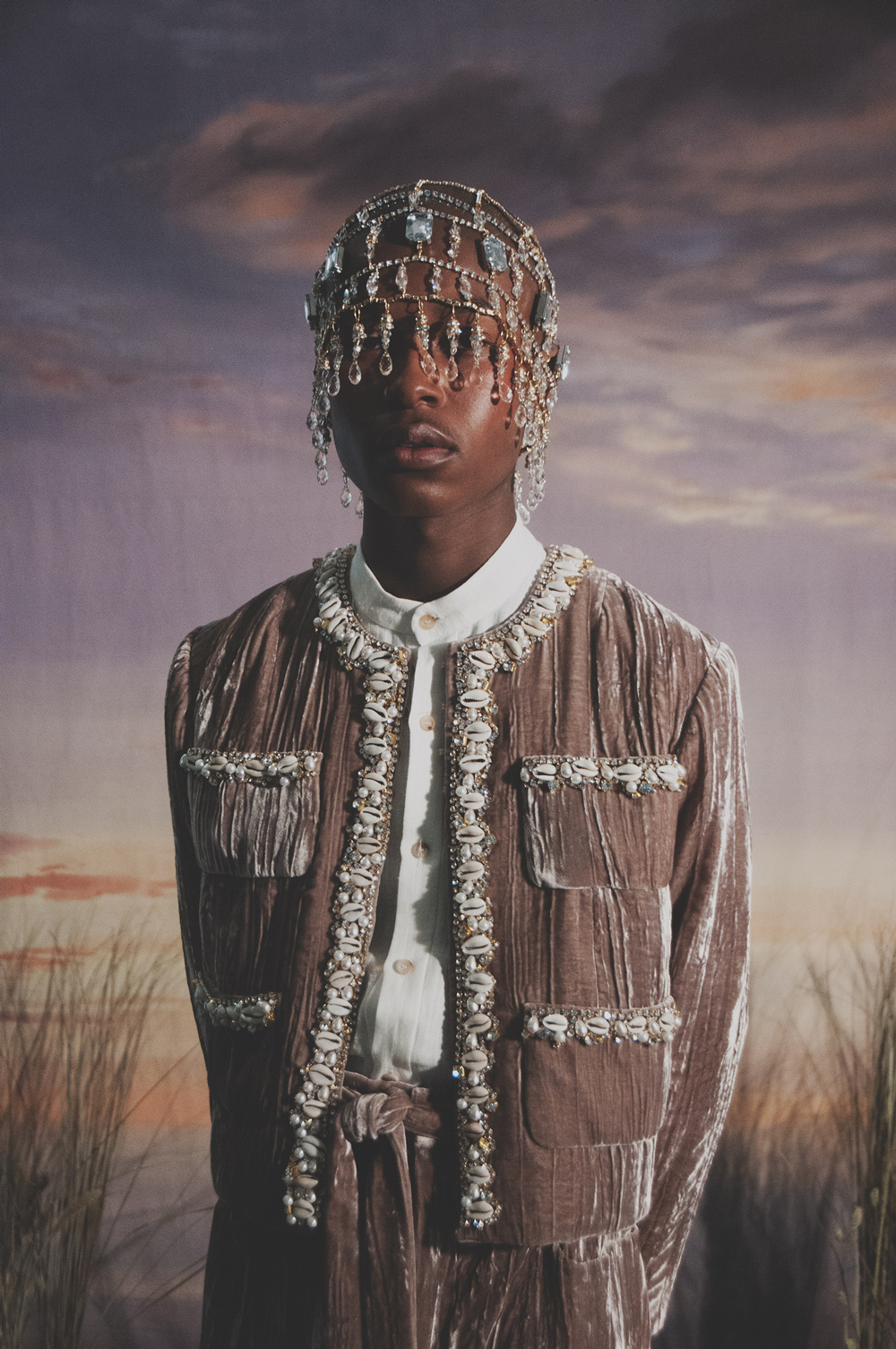

This laboured and academic approach has led to the creation of culturally specific clothes. Her collections often feature the use of cowrie shells as an embellishment and signifier of culture—the shells once being a currency in West Africa. Far from a token inclusion of symbolic identity—such as faux afros and synthetic dreadlocks—Wales Bonner celebrates black identity to the fullest, featuring a cast of predominantly black models as well as South Asian models (when exploring the Siddis, or Afro-Indians), reflecting the carefully deliberated decision of a designer seeking to reclaim cultural identities from the aftermaths of Eurocentric whitewashing. With black models wearing their heritage on their backs, Wales Bonner’s shows recall the poignant paintings of Kerry James Marshall and 2013 Turner Prize shortlist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye—incidentally a friend of Wales Bonner’s—their haunting paintings detail the intricacy, fragility, and dignity of black subjects, subverting the predominantly white tradition of portraiture while underlining a commitment to the beauty of blackness, both allusive and literal. Rather than exploiting culture superficially as a trope, these ideas inform the worldview of a designer who imbues them thoughtfully in her collections.

Apart from the strong foundation of intellectual thought that grounds her collections, Wales Bonner’s clothes exist within a broader context of black creativity, her collections at the epicentre of impressive collaborations with black artists within and without her cabal of friends. For her F/W 17 collection, Wales Bonner drew from the creative energy of black artists, featuring sound systems from the Notting Hill Carnival (a festival celebrating Caribbean culture in the UK); soulful, light-weighted harmonies delivered by Sampha, and poetry written by Yiadom-Boakye—collectively dreaming up an eclectic vision of roaming street preachers, friars and renaissance men who were inspirations behind the collection.

While focusing on menswear, Wales Bonner also examines the concept of masculinity, particularly that of black masculine identity. Her ideas and the consequent execution, largely influenced by the writings of James Baldwin, contribute to a nascent but broadening conversation about black masculinity in pop culture. From Frank Ocean’s full-throated admission that his first love was a man on his debut album Channel Orange, to Barry Jenkin’s Oscar-winning film Moonlight—which details the coming-of-age of a persecuted black gay boy named Chiron—pop culture is increasingly fracturing the performative hyper masculinity of black male identity, introducing nuance and vulnerability in their renditions. In “Good Guy”, Ocean croons about being taken to a gay bar, while in Moonlight, a teenage Chiron gets jerked off by a heterosexual friend who is similarly drawn to Chiron, exploring the homoeroticism that exists between black males—a theme that filmmakers such as John Singleton, director of the similarly coming-of-age film Boyz N The Hood, have hitherto shied away from. The significance of these works are not just their introduction of the notion of queerness into the vernacular of black masculinity, but also the fact that they are driven by black artists themselves, echoing the oft-repeated abbreviation, F.U.B.U. — For Us, By Us.

In the same way that Barry Jenkins and Frank Ocean are pushing the boundaries of black masculine identity, Wales Bonner’s meditative collections hark back to an era of black male dandies dressing up in their Sunday best, embracing style as a way of life rather than a sign of weakness. “I feel like I’ve seen enough images of black men looking really aggressive, very hypersexualised or ‘street’. That’s not how I think about men at all. That’s not the men in my life,” explains Wales Bonner in an interview with Dazed. With offerings such as chocolate-toned crushed velvet suits embellished with handwoven cowrie shells and Swarovski crystals, Wales Bonner disturbs the masculine medium of tailoring by introducing femininity through cinched waists, flared trousers, blush pink bouclé and silk cummerbunds among other intricate details. While the Wales Bonner man inhabits the interstices between masculine and feminine, he defies the presumed linearity that exists in the in-between. Not necessarily homosexual or bisexual, the Wales Bonner man, at his very core, embraces his self-possessed flamboyance and decorated refinement as a way to express himself, subverting the hyper-masculine black male whose vision of style solely consists of low rise jeans, oversized hoodies, and a fresh pair of sneakers.

By evading a simplistic understanding of gender, Wales Bonner articulates the sense that queerness is not a locus but rather a vast indefinite space, echoing the thoughts of queer theorist José Muñoz that “queerness is not yet here ... We may never touch queerness”. Similarly, through her mediation of different aspects of African culture and subversively introducing them into traditionally Western constructs, one should be careful not to view her collections as a collectively singular point for universalising an alternative vision of black masculinity, for to do so would be to deny the contextual specificity of her collections. By referencing different facets of African culture and articulating varied visions of black masculinity, she simultaneously zeroes in on a distinct aspect of it while intimating a broader cosmos that exists beyond, portraying African culture as a vast, uncontainable creative expanse whose surface she has barely skimmed.

It would not be a stretch to imagine an illustrious future for the 26-year old who has accomplished so much in such little time. As buyers begin putting in orders for Wales Bonner’s designs for both female and male customers, Wales Bonner has gradually introduced female models into her runway shows, perhaps opening up further possibilities for herself in the realm of womenswear in the near future. Regardless of her plans for the future, putting her feverish rise and innovative ideas into context, you can’t help but feel like you are already peering into the future of fashion—culturally informed and politically attuned, Wales Bonner is ahead of her time when it comes to being responsible for her creative endeavours, something the industry can hopefully catch up with.