"To adopt an ecological way of thinking–one that supports the full ecology of the planet, human and nonhuman–is to recognise the terrible intimacy of the nonhuman with us, and to accept this difference that rubs up against an inside us."Rebecca Tamás, Strangers: Essays on the Human and Nonhuman (2020)

The beginning of 2021 was marked by an unusual cool spell in tropical Singapore. Temperatures dropped below 22 degrees Celsius in some parts of the country. But while the first half of January was uncharacteristically cold, meteorologists forecasted that Singapore would soon see the mercury spike to 34 degrees. Fluctuations like these are becoming more common. It’s no longer possible to pretend that climate change is not happening within our lifetimes.

Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene is a collection of essays focused on Singapore and the environment. In his introduction, editor Matthew Schneider-Mayerson points out that the “environment” is not an external concept from the reader. It cannot be thought of as a niche interest any longer. This is where the concept of the Anthropocene is useful. Rather than merely framing the book around the physical environment, the term “Anthropocene” invokes a sense of time that implicates us all. The term, which gained popularity in the 2000s, is an unofficial unit of geologic time. We now live in an epoch defined by the transformative effects of human activities on the earth.

Singapore makes for a unique opportunity to examine the Anthropocene. As pointed out by several writers in the book, our position as a “Garden City” exists because our relationship with nature is marked by human intervention. In one of the essays, “Feeding the Monkeys,” Michele Chong argues that the national narrative around gardens “reveals a bias” for nature which can be “tamed, controlled and manipulated.” It is perhaps for this reason that so many of the essays in the book focus on those who have reduced or no capacity to act, those who are traditionally excluded from mainstream definitions of “Singaporean.”

Chong’s essay on the long-tailed macaque zooms in on some of our interactions with the monkeys in recent years. Deemed public nuisances, the species has been a target for culling (selective slaughter) among increasing human encroachment on their territory. Chong poses a provocative question–what would Singapore’s built environment look like if we consciously designed it for humans and nonhumans? Can we imagine a city that isn’t predicated on the domination of humans over all other species?

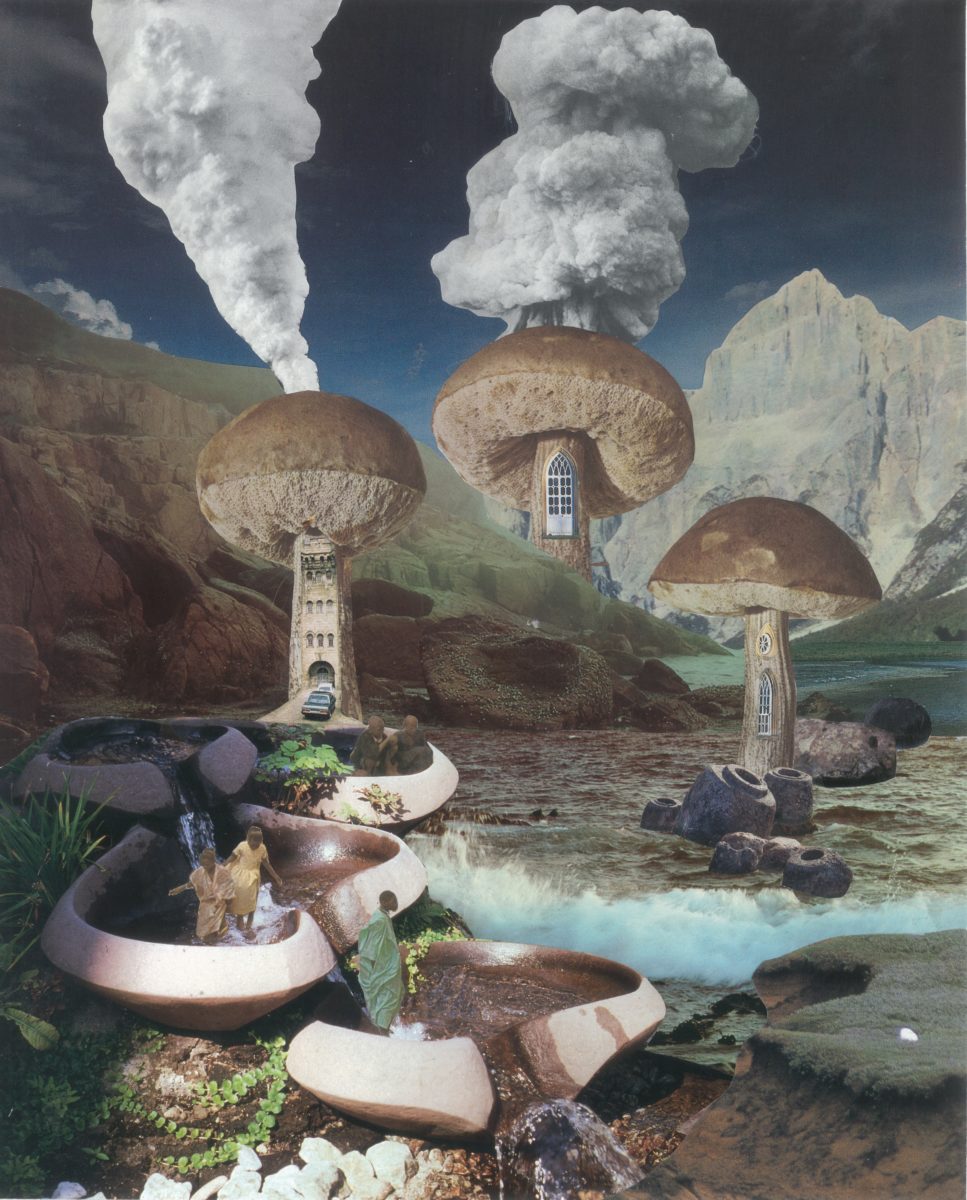

-(drop)-(pour)-(film-stills)_2018.jpg)

Other essays in the book also train their attention on the figure of the nonhuman in the Anthropocene. The collection’s titular essay by Neo Xiaoyun traces the history of the crab in both Singapore’s waters and its cuisine. Are current methods of cultivating crab ethical and does Singapore’s heavily meat-reliant cuisine need to adapt to address concern for the nonhuman? Lee Jin Hee’s essay on Javan mynahs, another species subject to culling, questions the demarcation between “invasive” and “native” species. As their names suggest, the birds originate from the Indonesian islands of Java and Bali. Since their introduction to Singapore in the 1920s, population numbers have exploded, triggering fears that they might disrupt “native” ecosystems. But given that ecosystems are in constant flux, what role should humans play in their conservation?

Non-Singaporeans also figure in the book, albeit tangentially. Sarah Novak’s look at land reclamation highlights the effect of the sand mining that reshapes Singapore’s coastline on communities in Cambodia and Vietnam. Heeeun Monica Kim’s “Loveable Lutrines” starts out as an essay on Singapore’s photogenic otter families but extends to become a discussion on climate refugees as our neighbours in Southeast Asia face the increasing effects from weather disasters brought about by climate change. Even the record rainfall and low temperatures from this January hit neighbouring Batam and Johor harder than they did Singapore. What should effective local action look like when Singaporeans are not the only beings impacted by our climate policies?

I am hesitant to expect from a book that raises thorny questions to also offer up complementary solutions. This line of thinking can stymie vital conversations before they even begin. Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene does not provide readers with a to-do list for climate action, but it is because the writers clearly do not back it. There is a liberal belief that a critical mass of individual action is the key to combating climate change. Aidan Mock addresses this briefly in “Singapore On Fire,” his essay on the fossil fuel industry. “Generally unfazed by individual lifestyle choices,” he redirects attention to systems put in place by policies and their importance in determining environmental outcomes. Bertrand Seah’s “Another Garden City Is Possible” outlines some of these key changes that need to occur for Singapore to effectively tackle the climate crisis. Focusing on decarbonising sectors like industry, transport, energy, and finance, Seah’s essay calls for radical change to the economy. None of these actions can be undertaken by individuals, no matter how dedicated they might be. Perhaps the only meaningful suggestion that the book makes for individuals is for them to band together to demand change, much like those assembled at the Singapore Climate Rally in 2019. Other possibilities exist, and they will need to be conceptualised collectively.

If anything, Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene is a time capsule of the ecological concerns facing Singapore now. The essays provide readers with tools to think with the environment and direction to situate ourselves within the world we inhabit. The friction between the human and nonhuman will keep coming up in the news–another forest cleared for a BTO development, a new technofuturist to farm vegetables, a more dangerous zoonotic virus. What will the next volume address? Will humankind have moved closer or further away from our climate goals? How many clear-eyed clarion calls will we need before we act?