For any active user of social media, it is not required knowledge to know the definition of a meme to comprehend and communicate with it. Before one gets to the meme, there is a set of steps: learn how to operate a smartphone or computer, install then navigate an app or program. But when we reach the actual meme, we get it. The understanding of a meme is instantaneous because we have been conditioned to read visual images, beginning with early exposure to popular culture through photographs and videos, as well as signs and symbols that we navigate in our lives. When British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term meme in The Selfish Gene (1976), he had intended it to mean a cultural parallel to biological genes—capable of reproduction in carrying information, replicating, and transmitting from person to person. The word meme comes from the Greek mimema, meaning “imitated.”

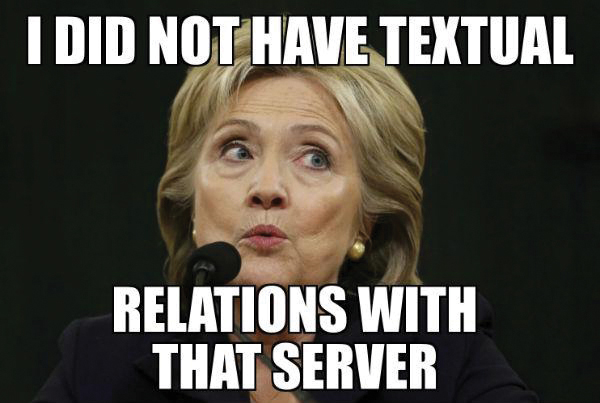

The Internet memes we are familiar with do not represent this original concept, since they are altered intentionally by us. Neither do they possess the ability to evolve, mutate at random or undergo natural selection. In that sense, the images we encounter outside of the digital screen are at times the memes Dawkins referenced (for example, the ubiquity of the human figure used to signal pedestrians crossing and its design variations). Internet memes hijack this original idea and are altered deliberately and creatively. However, Dawkins has clarified that at the point Internet memes go viral, its meaning returns to the term’s first definition; it is copied ad nauseum in the exact format (there are websites that provide the correct image in the precise low-resolution and the appropriate font) but evolve (through a change of text) and undergo natural selection (the best ones gain popularity and live on).

Setting the parameters of what memes and Internet memes are, memes featuring classical art with text fall into both categories. Images are usually taken from paintings and other visual artworks from the Classical, Medieval and Renaissance periods. But popular paintings from modern and contemporary art sometimes make the cut, think Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) and the $120,000 banana-taped-to-the-wall-and-titled Comedian (2020) by Maurizio Cattelan. These are known as image macros, a broad term that describes captioned images usually comprising a picture and a witty message in impact font, bold.

This bespectacled anime character is the protagonist from the 1990s Japanese anime TV series “The Brave Fighter of Sun Fighbird.” In a memorable scene, the humanoid character erroneously identifies a butterfly as a pigeon, and asks "Is this a pigeon?" The quote, along with a reaction image of the scene featuring the English-translated subtitle, has been widely used to express utter confusion. The meme has co-opted the image and intention of Magritte’s Treachery in this instance, extending the artist’s paradox through the character’s response but also paying homage to the metalanguage of both works.

However, before they are altered and become an Internet meme, the original artworks are borne from years of lineage, percolating through taste and sensibility over time. In this ambitious reading, can it be said that paintings reiterating popular subject matter certainly fulfil Dawkins’s first definition? For example, still lifes of flora and fauna, landscapes evoking the sublime, portraits of young women in various states of undress, and prominent figures including saints and royalty. Scroll through Instagram and one is greeted by roughly the same, generated by users all around the world immersed in the same visual language. The ennui across content and their creators is perhaps rooted in a similar concern the artists had, where a sequence of mastery laid at the feet of each creative—observing and emulating those around you before striking out on your own.

"The Internet meme is not a new phenomenon; the meme has been around for centuries and its study has been formalised within art history."

The Internet meme is not a new phenomenon; the meme has been around for centuries and its study has been formalised within art history. Among other tasks, the art historian identifies and classifies patterns in style, composition, technique, material, subject matter, then traces its dissemination through education and exposure, paying attention to the complicated relationships between student and master, patron and protégé, and its credibility lent through institution interest and market forces. The resultant exhibition text summarises—if you’re lucky—a narrative of how what you see came to be. Operating in meme culture requires some of the above skills executed on a smaller scale but quicker pace.

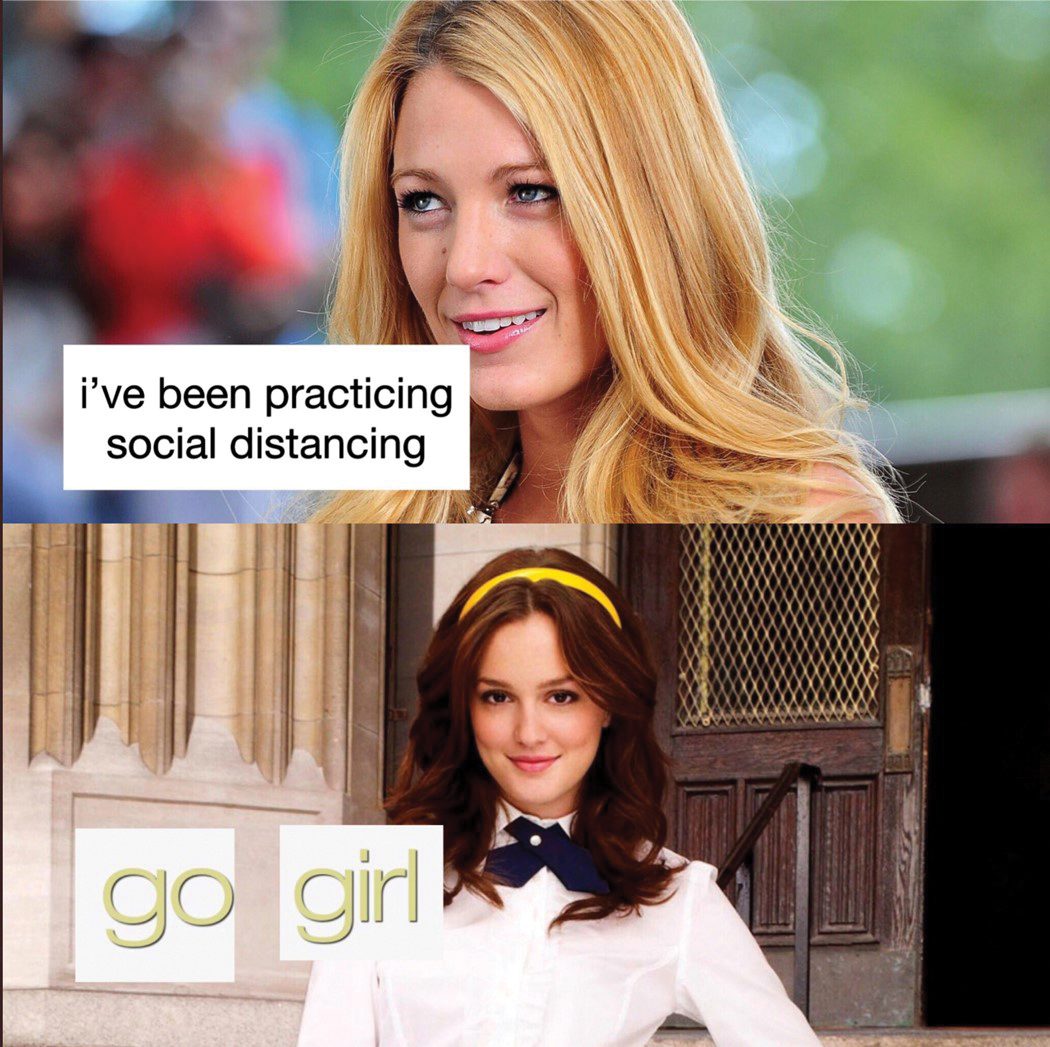

In April 2020, Gossip Girl title remixes began circulating on Twitter, comprising a two-paneled image macro in which characters from the U.S. drama television series, Serena and Blair, converse in a remixed version of the Gossip Girl title (which aired nearly 13 years ago). The actress who played Serena van der Woodsen, Blake Lively, shared her own spin via Instagram story, much to the delight of fans in their late twenties like this writer.

Are the resultant jokes astoundingly brilliant? No. But the perpetuation of meme culture in its easy adoption, mass appeal, and global accessibility does tell us where we are headed whether we like it or not. If art history asks how people make meaning in visual terms and, in turn, how we read and understand a world that is largely presented to us as visual information, then memes are impossible to ignore. Some of these have already dealt real world consequences, from hyperbolic accounts of the actress Mille Bobby Brown attacking others which resulted in the deletion of her Twitter to the rise of extremist symbols that found its way from 4Chan to the U.S. Capitol siege. On another note, in countries where youths form the cohort’s core, memes not only inject a sense of humour but emphasise the non-violent nature of their demonstrations. Pixels have been traded for paintbrushes in Myanmar and Thailand, where signs are often made with English translations to capture a wider audience. While the “okay” hand gesture has become a sign for white supremacy in the U.S., the three-finger-salute—with the thumb on the little finger—has become a call for solidarity among protestors, originally depicted in the Hunger Games books by Suzanne Collins.

Within the art world, Beeple’s $69 million auction result is an event participatory of a larger movement. Many evangelise the democratising nature of NFTs in according digital art value through sole ownership, but the price tag belies another revelation, that those who partake in meme culture already broke through the first barrier. Art is no longer reserved only for the highly educated to perceive but are now flattened images accessible and open to alteration for all; one does not need a specialised degree or expertise to decipher a contemporary artwork or spot the next emerging trend—the language of memes via both Dawkins’s original intention and the Internet’s version is knowledge enough.

Check out the following meme accounts on Instagram: @sgmuseummemes, @jerrygogosian, @classical_art_memes_official, @bradtroemel, @classicalfuck