The Artist as Brand

by Kam Dhillon

The Artist as Brand

by Kam Dhillon

Consider art as the ultimate benchmark of connoisseurial consumerism through a chronological conflation of art historical moments such as Warhol's use of ‘cultural capital’ to demystify the success of art and fashion collaborations. By applying a lens to artists and designers like Bjarne Melgaard, Eckhaus Latta and Amalia Ulman, we detangle the artist playing as brand in a conflicted celebration and subversion of commerce in contemporary culture.

It's not easy to gauge the difference between an artist's complicity or ironic distance from corporate aesthetics, given the varying range of creative crossover projects occurring in contemporary critical art practices. Today, commercially fruitful art and fashion collaborations seem ubiquitous, as evidenced everywhere from Prada's Spring/ Summer 14 commission of six graffiti artists and Bottega Veneta's work with Alex Prager and Ryan McGinley to Louis Vuitton’s collaborations with the likes of Yayoi Kusama, Takashi Murakami and Richard Prince. Yet, there is also a return to artists probing fashion as a subject of both critique and celebration in their art practice today.

Appropriating the tropes of corporate visual dictums is no new artistic strategy; in fact, it emerged as a discourse at the height of media-obsessed, post-Vietnam age. Douglas Crimp's Pictures exhibition in 1974 privileged artists who culled images from a sea of representations, predominantly inspired by media and commercial advertising which increasingly became the signifiers of a lived American reality. Fast forward a few years, and branding and commerce have become directly implicated with the hand of the artist in a range of collaborative projects that really took off in the '80s. In 1985, Absolut Vodka initiated a long collaboration with contemporary artists. Beginning with Andy Warhol, the campaign went on to showcase the work of dozens of artists—a perfect example of the immense power of art to add value to a brand.

Is it just the artist’s cultural bravado that the fashion world finds so seductive? Maybe, but fashion’s flirtatious passes are returned with more than just a fleeting touch, with art bibles like FlashArt and ArtForum regularly featuring articles on radical designers such as Helmut Lang and Vivienne Westwood, and a smattering of ads from heavy-hitters like Saint Laurent Paris and Prada.

Fashion itself has grown more artistic, with ever more conceptual designs, daringly provocative advertising campaigns, and theatrically spectacular shows. Clothing labels like Calvin Klein initiated major campaigns featuring the kind of sumptuous art photography previously reserved for opulent and specialist fashion magazines. Sporting a logo but otherwise devoid of text, these advertisements aligned the brand firmly with image.

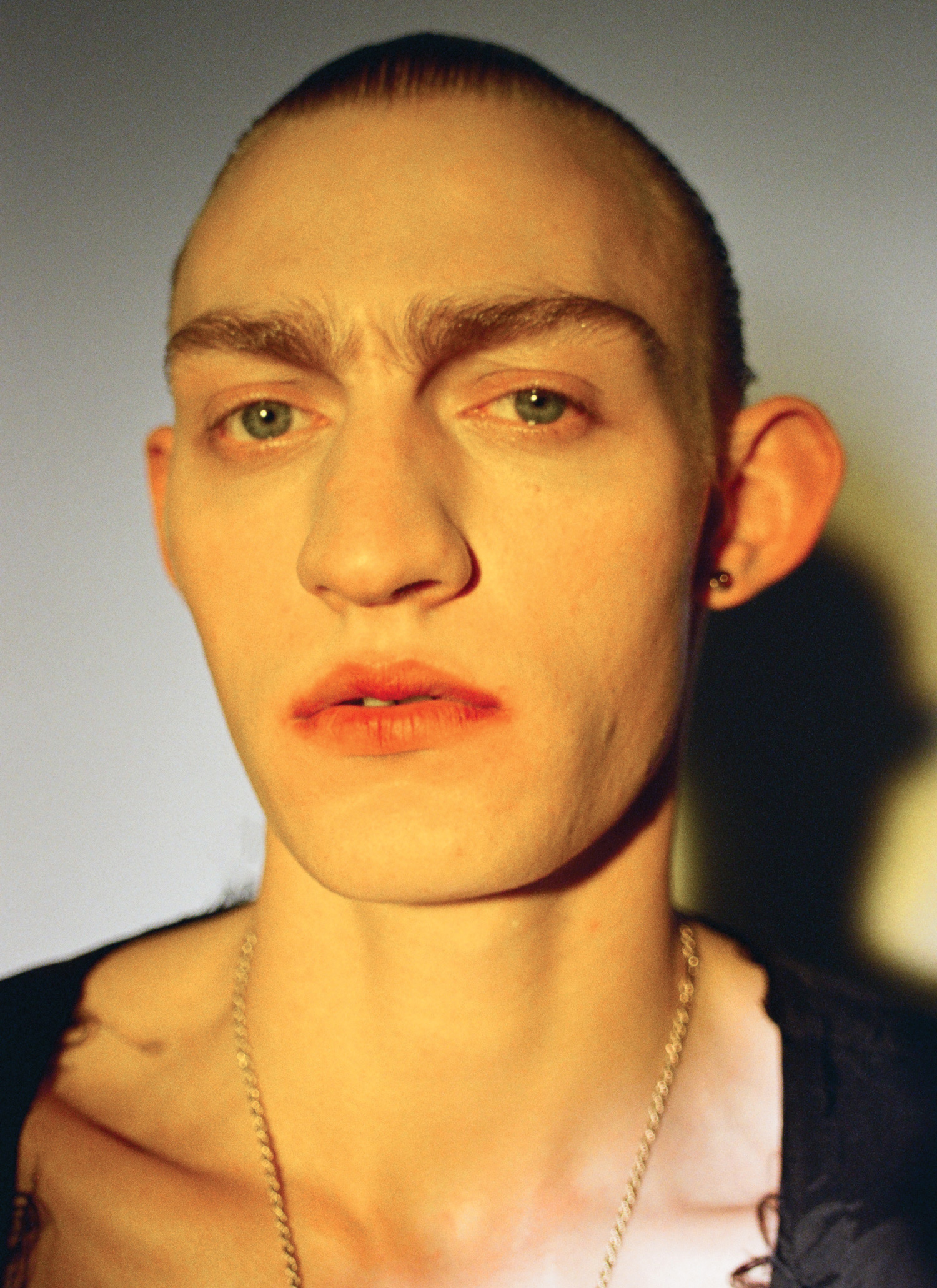

Beyond fashion embracing the visual language of high art, commerce remains a popular aesthetic project in critical art practice today. Norwegian artist Bjarne Melgaard and New York-based design duo Eckhaus Latta came together for the artist’s Ignorant Transparencies show at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise Gallery in New York. It’s a harmonic, creative union perfectly emblematic of a current synergy between art, fashion and in a larger part, commerce. Both the designers and artist are associated with the particular cultural cachet of the downtown New York art-scene. Though such collaborations seem organic and logical, it’s also a calculated strategy on each side to cash in on the brand power of the other’s media-perpetuated ‘coolness.’

Are these feverish couplings between art and fashion figures today simply symptomatic of a contemporary cultural condition completely rooted in the language of commerce? We live in the age of the interface, and commercial strategies infiltrate every corner of media, from product placement in music videos to advertorial content posing as traditional journalism. Even younger artists today, such as Amalia Ulman, devote entire artistic projects to probing commerce in culture. Ulman’s diverse artistic practice spans painting, poetry, essays, sculpture, video, Instagram uploads, a confessional Facebook presence, and Skype lectures.

Her manicured persona negotiates a hyper-real aesthetic of opulence, beauty and luxury. In an interview for a past issue of Kaleidoscope Magazine, the Serpentine director Hans-Ulrich Obrist asked Amalia who her heroes were. She responded with “Colette, Chopin, The Economist, Kusturica, Whit Stilman, Insomnia, artificially aided insomnia, yerba mate, Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers memorabilia, Homes & Gardens, french manicure, cashmere sweaters, Poundlands, Euro Stores, Dollar Stores, and Carla Bruni.”

These are all ripples of consumption that define our daily, contemporary existence, and it’s only accelerated by digital technologies. All of the things she mentioned are easily relatable for us as viewers and co-consumers. Thereby, her Instagram feed (a now archived component of her art practice) has become a visual extension of this strategy, where she consistently appeals to a sense of mass luxury and DIY prettiness through snapping spa days, facemasks and other beauty regimes.

These symbols of mass-luxury and accessible affluence are what Emily Segal (a brand consultant who is a part of the trend forecasting group K-Hole) identifies as a shift in how luxury is conceptualised. The old model of luxury was based on the consumption of rarefied goods, and is being replaced with an emergent model of luxury that is informational and based on how much control you have over big systems of information. So, Amalia Ulman taking selfies in an airplane bathroom might allude to a luxurious jet-set lifestyle of an artist with growing international demand, but by using toilet paper as make-shift, avant-garde apparel, it becomes an aspirational aesthetic yet wholly accessible to anyone who can afford a Ryanair ticket.

Though similar to the zeitgeist of the ‘Picture Generation,’ these artists are self-branded digital natives, who navigate the saturated flux of the digital terrain with relentless speed and steady track-pad conviction. Unbound by the technological limitations of their forebears, their searches for material are wild and multiple in direction, facilitated by multiple tabs, hyper-fast search engines with sophisticated algorithms, instant messaging and ubiquitous high-speed connections to the internet. This new trajectory, leading through appropriation, seems to be shifting into another ethos entirely, one not born in resistance to appropriation, but that has fully absorbed its tropes. Objects and images designed within corporations now exist as mere substance amidst a dense, delirious field of what French theorist Jean Baudrillard dubbed 'simulacra.'