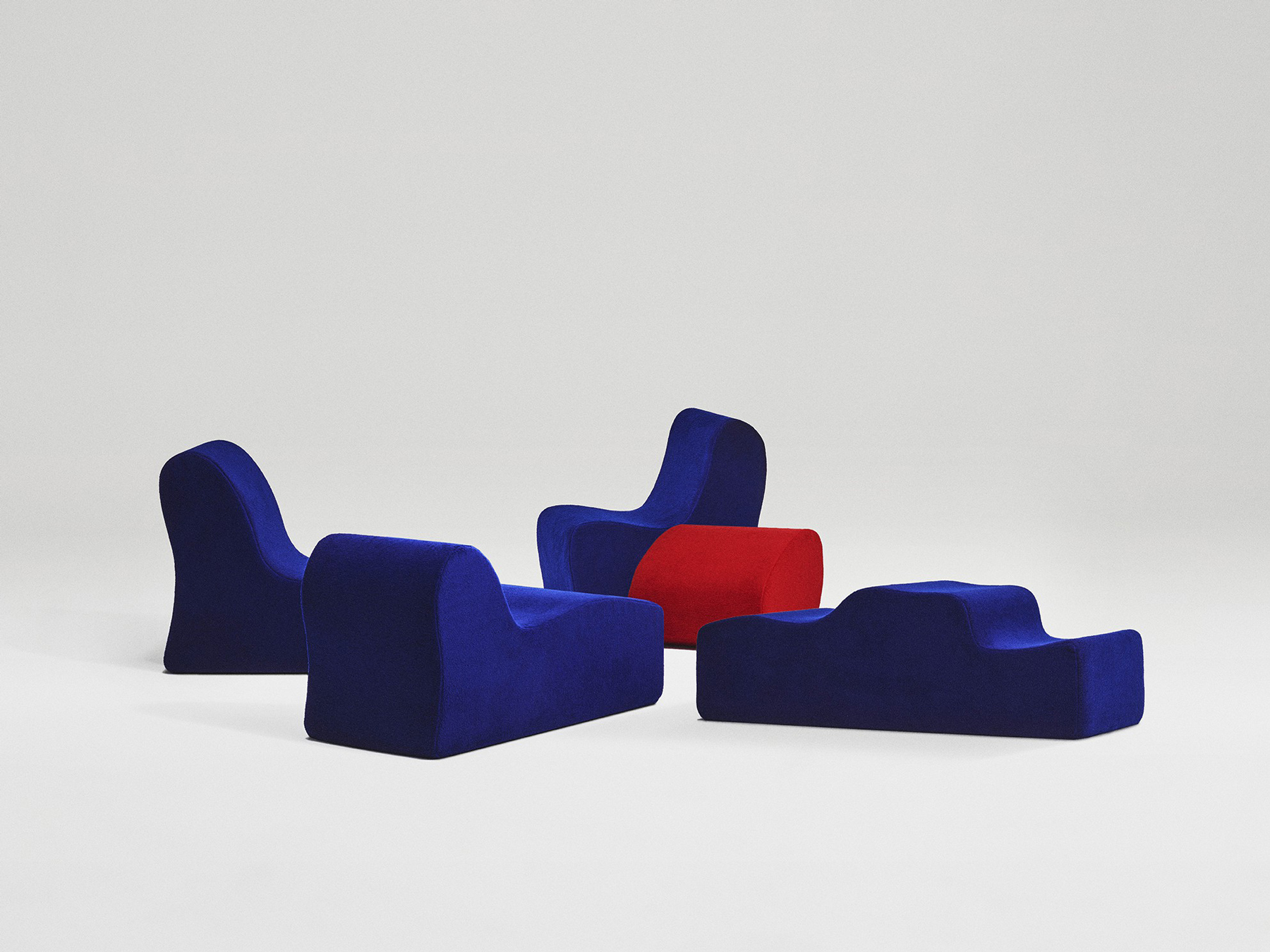

Raf Simons is no stranger to furniture design—prior to an astounding fashion debut with his eponymous menswear label, Simons trained in industrial design with a focus on furniture. Sometime during the next decade, Simons would search for a textile appropriate to a line of Fall/Winter coats for Jil Sander—one that ended with Danish fabric company Kvadrat. The brand commands a well-earned respect in the industry. With an emphasis on simplicity, innovation and design, the quality of their textiles is undeniable. Kvadrat fabrics upholster some of the most prominent architectural landmarks, including the Guggenheim Museum, the Walt Disney Concert Hall and Jean Nouvel’s 2010 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion. Far beyond conventional design applications, the Danish company also actively collaborates with artists such as Thomas Demand and Roman Signer in art installations. So a collaborative effort between Simons, with his endless creative energy, and Kvadrat, with their willingness for exploration, is unsurprising but welcome all the same.

Drawn together by a deep appreciation for craftsmanship, the resulting collection displays exceptional style, with great attention to detail and texture. Simons manages to translate the aesthetic sensibility of his fashion into pieces ultimately destined for a more domestic setting. While almost sculptural in quality, the resulting furniture does not seek to overpower or announce their presence in an interior space, asserting themselves instead through a quiet, refined elegance.

Curious about the intersection between fashion, furniture and textiles, Hettie Judah talks to Simons to find out more about the inspirations and process behind the collaboration.

At the point when you discovered Kvadrat you were at Jil Sander. How did you find out about these textiles?

For the Fall 2011 collection I was looking for a fabric that gave the possibility of doing garments that almost stood upright; the women’s collection of that season was linked to mid-century modernism when fabrics were much heavier and rougher because that was still in the period after the Second World War. I was thinking of going back to the original feel of all those fabrics, and that brought me to Kvadrat actually—to an environment completely away from fashion.

It was only when I got their textiles into our office and started to go through them, that I discovered other aspects of Kvadrat that fascinated me so much, such as the colouration, the high quality and the interesting impact of the melanges (mixed colours). I think their melanges are incredibly chic; they have timelessness and a kind of modesty.

The Kvadrat fabrics that I used in that collection are rougher and heavier fabrics than are used in the fashion business. The textiles were woven so compactly and there was a certain kind of thickness to them so that they perform almost as if they were contemporary bonded fabrics, but they looked more authentic. I think this authenticity was a combination of the fact that they are developed for furniture and that they were grounded in the north. That was very attractive to me, because the collection that we were dealing with was very feminine and we were dealing with almost couture-ish aspects from the mid century.

How did the idea of a textile collaboration with Kvadrat come about?

They just came and asked me. They contacted me through Peter Saville, their creative consultant. They knew that I did something with their fabrics and they came to Antwerp. We had a meeting and I decided immediately to do it.

How did you approach the collaboration, what was your experience like working with Kvadrat?

I’ve never worked with a Danish company before, but I was very aware and always a very big fan of Danish design—Hans Wegner and all these people. I think that same combination of strength, quality and modesty was definitely something that I found right away when I started working with the team and with Anders (Byriel); and you feel it all over the collection. In the early stage of collaboration my intention was not to create a shock effect, or to go away from what Kvadrat do—it was the opposite, for me it was very much about entering that world, showing how much I love it, showing how much I respect it but giving it a new kind of twist.

Do you think much about textiles in the context of furniture?

Actually I look around a lot—it is something deeply ingrained in me because I trained as an industrial furniture designer so I always follow design very intensely. When I look at the furniture produced by the major manufacturers, I see amazingly beautiful fabrics, but often I think they are very traditional—in their colouration or in their juxtapositions of colour; there are a lot of grey tones or beige tones.

Or, sometimes they become too experimental and you feel that it’s not going to last. Often with very modern designs they throw in a lot of synthetic fabrics to make it glamorous, but to me it starts to look object-like. It’s something I don’t like very much in relation to interiors. That’s what annoys me in the furniture business at times, that I think people are either very safe with their colourations or they go too experimental—like silver with purple.

I think that one thing that should never be forgotten when we think of fabric in relation to interiors is that whole domestic feeling. Whether you have a design orientation, an architectural orientation or you have something much more cosy and small and domestic. I think fabric in relation to interiors should relate to your body. I could not sit on a piece of furniture and feel comfortable at home when it’s this new, high-tech, shiny, glam-impact fabric, it just doesn’t feel right. It’s something I think that Danish design never had—Danish design always had that warmth to it, that human aspect.

What’s the difference between developing textiles in fashion and developing textiles for furniture?

The aspect of durability, the fact that they have to last, is the crucial difference between fabrics used in fashion and fabrics used in furniture. Not that we want to craft fabrics in fashion that are not going to last, but especially these days with fashion being so fast, it is not a problem if they don’t survive time. That is not the case with furniture. The crucial difference to working with a company that is developing fabrics for the fashion industry or for the furniture industry is that of time—the whole Kvadrat process is extremely, beautifully slow. The whole process in fashion is extremely ugly and fast. It’s such a huge difference.

You mentioned Hans Wegner—what historical inspirations from the design world did you have in working on this particular collection?

I have a lifelong passion for that period of design creation—whether it is fashion, architecture or furniture—grounded in the mid-century. I always liked the idea of the mid-century, when people were dreaming about the future but there was still this kind of strong obsession with durability. I think that most things that were designed by amazing people in the 1950s and 1960s have really survived time in such a beautiful way.

It made me think a lot about working with Kvadrat, because a lot of the design that we were talking about was Danish design, which was very powerful in that period. It has this beautiful balance between a modernist approach and that sort of romance.

There were some people who were quite inspiring to me, such as the French architect/ designer Jean Royère; I’m extremely obsessed and interested in his work because he was the only male dominating design figure at that time who also dared to be very feminine—very feminine in the choice of his colouration, very feminine in the language of form… Then you would have somebody like Hans Wegner who dared to be very experimental but was still really rooted in the ideas of quality and modesty.

You would have people like (Charlotte) Perriand and (Jean) Prouvé who were fusing the idea of industrialising processes with the idea of domestic and avant-garde design, but were very socially aware: doing a lot of things relating to the public environment and schools and institutional buildings. I think that most of these people had a quality to them that is so lasting and so in balance with their time that even 50 years later it still feels so relevant.

Can we talk about designing the collection, and how you went about designing a textile collection?

We started with strong inspiration and a lot of imagery that was around people like Royère and Perriand and some of the Danes, and then we also brought in a lot of fabrics from fashion—fabrics that are completely unusable in the context of furniture because of how they are woven—bouclés and tweeds and all these kinds of materials. I was very fascinated by how the colouration process or weaving process in fashion textiles does not have the same limitations, and then seeing how we could transport that into the furniture environment by completely readapting the yarns and the qualities and the weaving process in order to make it durable.

I got quite obsessed with all the qualities that had an origin more in the kind of bouclé or tweed environment and we started to re-colour them or bring colours together that are unusual; like when the pink comes in with the black and all these unconventional combinations of colours. Because of the density that is needed for furniture in order to make it survive in the long run, it becomes even more interesting. What is fascinating is that some of the colourations on the tweeds almost have a painterly impact.

Were you inspired by specific garments from your fashion collections?

No. The only thing that relates back to the Jil Sander collections is the colouration of the unique colours and re-colourations in this collection. We were very strict about a particular blue or a particular orange. It’s something that I also introduced very firmly at Jil Sander because it was a brand that was originally defined by greys, marine and beige tones, and over the years I introduced a lot of colour into the brand.

During my time at Jil Sander and now at Dior, when it comes to colour, I like the idea of changing the way your eye looks at things. I’m interested in the intensity of a colour which is maybe present only in a very small amount. For example in the middle of a flower there is maybe a very specific strongly pigmented orange or pigmented blue or red.

With the melanges in this collection, you see then from a distance and think that it looks quite interesting, but them if you get up close you would notice a weird pink with that black and white, or a strongly pigmented electric blue—that’s what I’m fascinated with.

So you’re trying to find strong colours that have a kind of warmth or natural quality to them?

Yes. When you use colour it has to last in the context of furniture—when I need to make a decision on upholstering a sofa I can take a very long time to make that decision. I’m very different when I want to buy a pair of pants or a shirt—with that I just go for it, and if you’re not so convinced about it a couple of months later it’s not such a big problem. But purely from a practical point of view, the idea of upholstering a three-seater sofa and two months later you’re not sure about it anymore—to do it again is such a hassle.

This collaboration has taken a while to work on—you described it as a slow process?

It’s incredible—I think it’s almost two years now.

In this time you’ve had so much happening in your own life that it’s unbelievable that you’ve had the energy or time to continue with this collaboration.

Never in my life have I done only one thing—I get bored like hell if I do only one thing. I have always been doing several things at the same time—I was doing my own brand as well as, for example, art curation and teaching at the University in Vienna for 5 years—always combining different things. I get bored—I sound so spoilt when I say that, but it refreshes the brain so much when you’re always going from one environment to the other. I don’t like to look at fashion only from a fashion perspective, and I like the idea that when I’m doing something with Kvadrat, I don’t only approach it from a furniture perspective.

Is collaboration very important to your practice in general?

Yes, because I admire a lot of other creative people. My drive is partly the drive of other people’s creation. I was always interested in how things could come together with other people—an artist, another designer, furniture, education, when you come into contact with a younger generation. I’m obsessed with the idea of inter-generation communication; it’s something that I think is the ultimate activator of evolution. I don’t believe so much in the idea of looking in one direction.

Are you going to continue working with Kvadrat? Is there going to be another collection?

Yes, of course, it’s going to be an evolution—this is the start of things!