For Everyone

by Simon Wu

Image courtesy Torso

by Simon Wu

Image courtesy Torso

I brought my green, medium-sized, Telfar bag on a trip to the dentist with my mother recently. She brought her pink, ruched, faux-leather Victoria Secret bag. The first time I showed my mother, a Burmese immigrant who now runs a sushi business, the “Bushwick Birkin,” she pulled at the seams, rubbing the vegan leather between her fingers, and asked me how much it cost. She got her bag from Victoria’s Secret (which she refers to in a shorthand as just Victoria, like a good friend) for $10, reduced from $90 after an army of coupons. When I told her $150, she gasped. “For that?”

My mother’s and my differences in taste can be roughly accounted for in age and geography but perhaps most significantly in class, my parents being middle-class immigrants while I’m a college-educated, gay twenty-something creative professional living in Brooklyn. Telfar’s brand slogan is “Not For You, For Everyone,” borne of Telfar Clemens’s love for the clothes of the “every person.” What relation does someone like my mother have to that “everyone”?

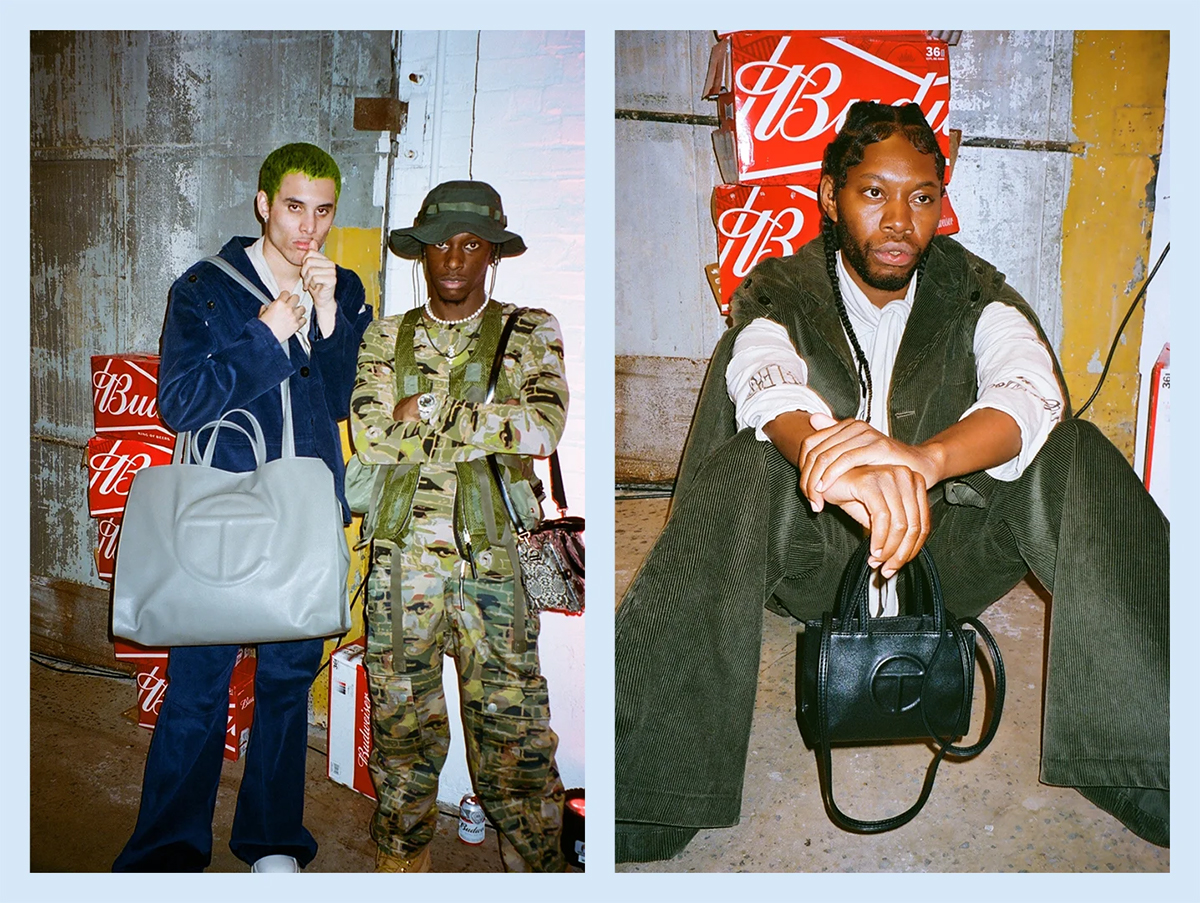

Telfar’s aesthetic is often drawn from the symbols and sensibility of working class people like my mother: the Talbots catalogues that belonged to his aunt, Budweiser, White Castle (he redesigned their uniforms in 2017), K-Mart, the newly arrived immigrant naïf (known in the West African diaspora as a Johnny Just Come). Avena Gallagher, his stylist and collaborator, has described how Clemens has always been interested “in what everybody wears rather than what the rare person wears.” This fetish for the authenticity of the working class isn’t particularly new (see Balenciaga refugee bag etc.), but Clemens’s appeal to the “everyone” feels different. It rides a political impulse towards “inclusion,” in the spirit of many young black/queer creatives who come from “everywhere.” Or he just wants to include all of his friends.

"It rides a political impulse towards “inclusion,” in the spirit of many young black/queer creatives who come from “everywhere.”"

Telfar’s Instagram account reposts almost anyone who poses with the bag, and people are very proud to show their bags off to display their allegiance. Part of Telfar’s appeal is a throwback to a flashier style of conspicuous consumption. It plays with the racialized connotations around the iconic possessions of the working class—gold chains, dollar bills, Hennessy, fast cars. Telfar retools this type of visibility in the service of a new racial and sexual vanguard, a virtual and real community of creatives who haven’t historically been represented in fashion.

The thrill associated with this kind of flashy consumption comes from how it plays against the norms of an elite, white class that often prefers inconspicuous consumption. Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, in her book The Sum of Small Things, outlines a theory of the “aspirational class,” an NPR-tote carrying, yoga-practicing, Whole Foods-shopping group of neo-yuppies who find it gauche to flaunt wealth through brands, preferring instead to spend their money on “ethically” made goods and services. This is the difference between the adjunct creative writing professor at Yale making 30k a year who buys heirloom tomatoes at the farmer’s market and the carpenter who makes 100k a year. Knowledge and cultural capital trumps economics in the “aspirational class” because in the information economy they are gatekeepers to upward mobility.

Image courtesy by Charlie Engman

Who exactly are all of those people in the Telfar pictures? They are celebrities, like Lizzo and Selena Gomez, but most of them are aspiring creatives, black-adjacent, queer-allied stylists and artists and photographers and Instagram models. I’d think that they’re more like me than they are like my mother; more like the creative writing professor than the carpenter. Avant-garde culture of the type that surrounds me in Brooklyn or the art institutions I work within that shares a proximity to advanced capital—an intimacy to the absolute 1% of the world I didn’t dream of as a kid. Telfar’s high-fashion transformation of the “every person” sensibility (on top of charging $150 for a bag) paradoxically alienates it from its originators, like my mother, or at least renders it inscrutable to them.

But even if I bought my mom a Telfar bag, I don’t think she’d want to wear it. It doesn’t really go with her style. I enjoy my Telfar bag, I like the community that it brings me into; my mom loves Victoria’s Secret and PINK and their bags and clothes. We’re both interpolated in systems that exploit our desire to have taste and individuality in consumption. It’s fun. The rituals of retail have always been somewhere we could connect. When I was younger, at JCPenney or Old Navy or Macy’s she could ask for my opinions on blouses and skirts and (as her gay son) I could give my honest thoughts. She’s never been fazed by the threat of urbane taste as I moved to New York; she likes what she likes. So maybe sometimes I wear my Telfar bag with my mom’s sushi uniform and Dickie’s, ironically but also earnestly, and preempt its appropriation into high fashion in our makeshift version of the “everyone.”

Background:

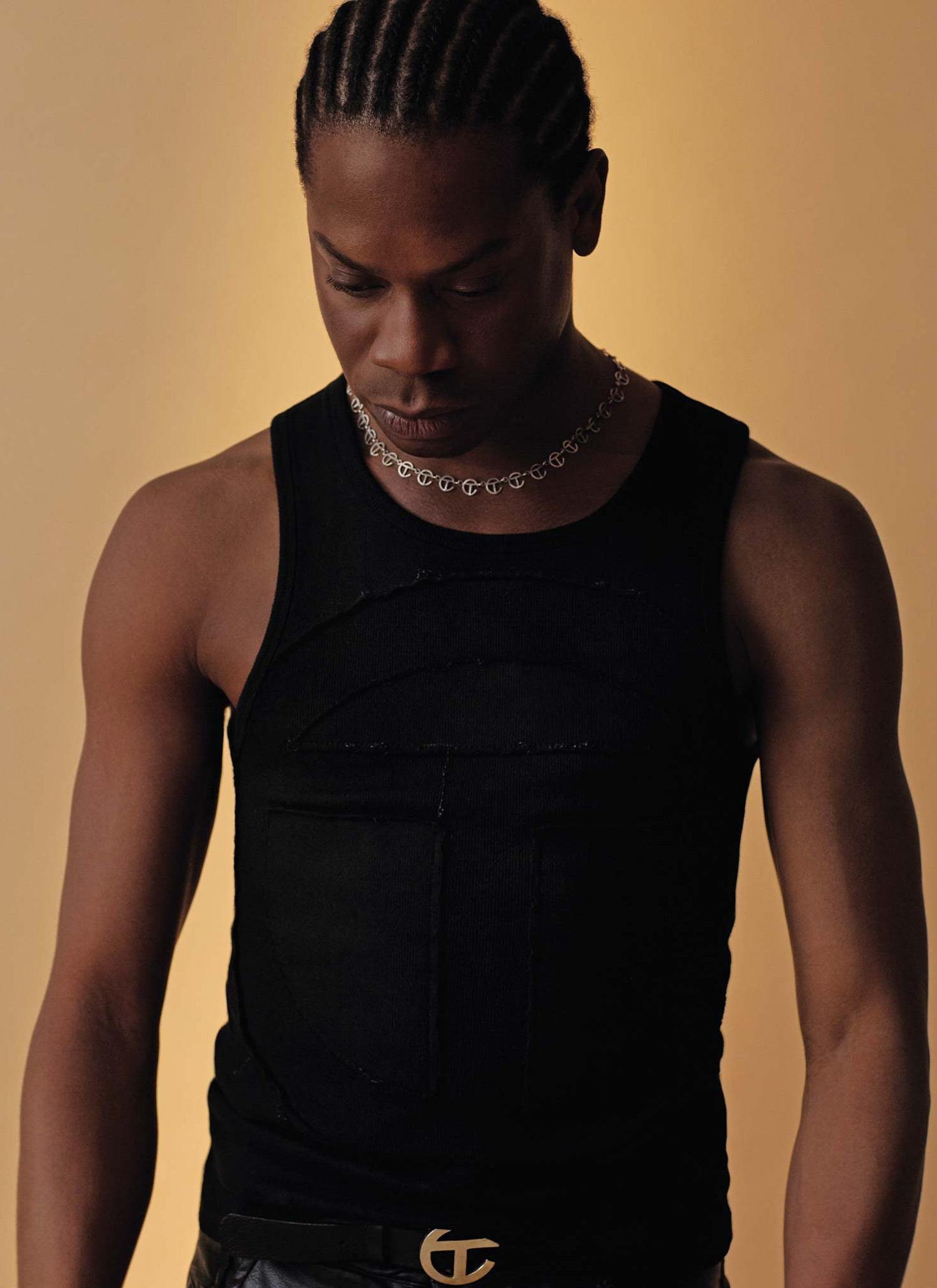

Telfar is a unisex fashion brand founded in 2005 by Telfar Clemens, a young Liberian-American and Queens native. Clemens, who is gay, describes his brand as “genderless, democratic, and transformative,” building his runway collections around a community of mostly queer POC creatives. The clothes are deliberately utilitarian, drawing inspiration from the standardized fashions of globalization. In past shows, Clemens has zealously repurposed the Budweiser logo, put Beats headphones on his models during runway shows, and redesigned the White Castle uniform. Clemens’s most popular product is the shopping bag, modeled off Bloomingdale's shopping bags which come in three sizes. Introduced in 2014, the Telfar bags are designed in vegan leather, branded with a signature “T” logo, and priced from $150 to $257. In the last few years, the bags have reached a near cult-status, frequently selling out on Telfar’s website. Their status as the it-bag for a new wave of creatives has led the Twittersphere to dub the bag the “Bushwick Birkin.”