How to design for the end of the world:

Gucci’s Epilogue

by Joshua Comaroff

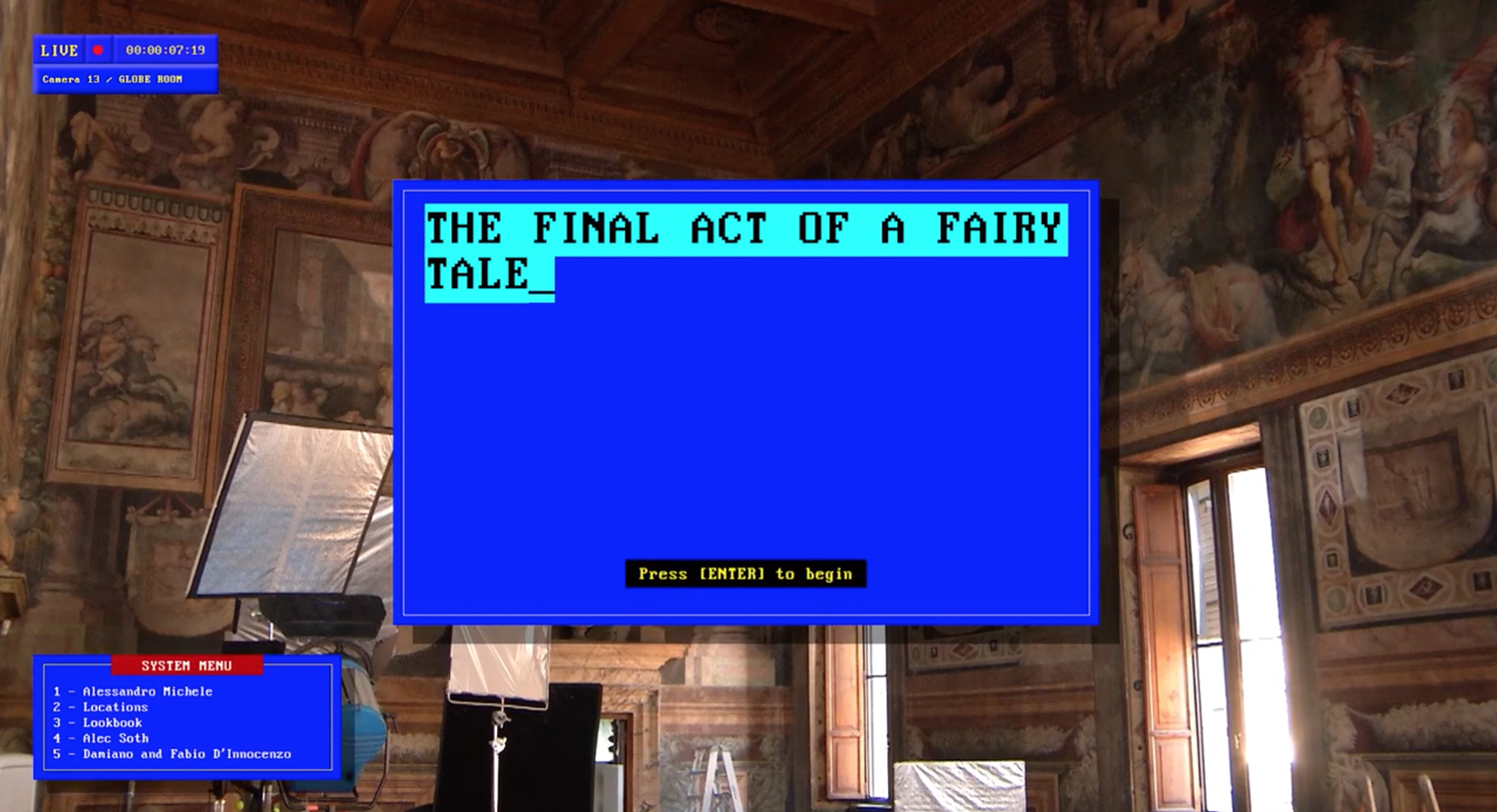

What does it mean for fashion—rocked by every conceivable type of crisis in its Very Bad Year—to contemplate its own end and afterlife? This is the question posed by Alessandro Michele in Epilogue, Gucci’s extraordinary non-show for Milan. This is described as something hilariously unaesthetic, and intentionally boring: the live stream of an ad campaign “created by the models themselves.” The result is not boring. It is an attempt by Gucci to bear its soul, and with it the ambiguities of design and commerce in a time of crisis. This is of no small consequence in an industry that has struggled to respond to revelations of various scandals: race and class discrimination, unsustainability, and irrelevance in the face of a pandemic. Michele’s work, evident from its title, is an attempt to capture the death-throes of an era as much as the end of another menswear week. It took place on the last day of the event and is also the third in a trilogy of presentations by the brand that attempt to fundamentally question the future of the industry. Epilogue calls this “the end of a fairytale,” a moment to “question the rules and traditions of fashion.” And to imagine something after. Michele is showing us The End, as it looks from the director’s chair of Gucci. There is little melancholy in this gesture. The Director appears less interested in mourning a lost world, so much as playing among its fallen columns. The composition of Epilogue recalls old MS-DOS software, with pop-up windows containing text—read in a robotic text-to-voice drone or by the designer and photographer—random imagery and looks modeled by their own creators. The whole impression is of something raw, like looking through the un-designed interfaces of a CCTV panel. Images appear side-by-side in faux-random juxtapositions, as if generated by a glitch in obsolete software. Blue crash screens and random number strings blink on from time to time. The entire venture seems on the verge of failure. And into this evolving pastiche, the voices of Michele and his collaborators speak about the excitements and difficulties of making art.

This reads as nostalgic, a throw-back to a naïve moment in which the digital was beautifully awkward and unpolished. Pixels were evident, and a clear distinction maintained between the human and its simulation through imagery. At the same time, this rawness gives one an impression of intimacy; we are peeking at Michele’s screen, with its progress photos, diary entries, and “inspo” images. He calls it “looking inside the mechanism.” It feels like sitting in the control room: of media, of fashion, an ad agency, or of some crisis center. It could be any, and all. As with all creative attempts to reject aesthetics, Epilogue feels highly aestheticized. It is like a catalogue of anti-art appropriations: cables and tripods and temporary lighting, detuned and overexposed “raw” footage, crop marks and numerical image labels. Such imagery pervades the backdrop of the screen, in running shots of the beautifully floodlit Palazzo Sacchetti. (In an act of ostentatious social distancing, Gucci’s presentation was live-fed from Rome.) Half-ruined and blasted with yellow light, it must be a nod to Kubrick. Nothing much is happening. It’s the familiar lull before a show, with all of its nervous boredoms and small tasks. Masked workers walk to and fro and makeup is applied. It’s all deeply trivial but fascinating in the voyeuristic way that closed-circuit footage can be. We watch models get dressed, with clothes racks standing in silent rows. Epilogue’s play of visual fragments matches the aesthetic of the collection itself. The clothes are beautiful, certainly. But there is a distinct thrift-shop vibe—as if the looks were assembled by an immaculately tasteful Goodwill shopper, in some post-Capitalist idyll of collapse and rebirth. The clothes have the glamor of another dark and devalued era: hence the 1970s hausfrau smocks from a pre-flash-fashion moment in which tailoring was more intensive and gendering gentler. The combination of such references, old-looking but newly remade, are played against superimposed Gucci touches of leather and metalwork. The recessionary romance of this post-hippie-ism is amplified by the collection’s refusal to distinguish between gender or season. The crisis of our own moment, in which basic categories of self are reconsidered against a backdrop of immobilization and de-naturalization, comes to roost here in the rejection of traditional hallmarks of style.

"What is interesting is Michele’s suggestion that a ruthless transparency, a brutal light shone into the excesses of fashion’s own faded glamour, is a route forward from a crisis that looks to become endemic."

This anti-aesthetic—by now a hoary tradition of its own—embodies a very controlled understanding of the image and its production. This is a subject which Michele broaches directly in saying that he wishes to dissociate the narrative of the show, the productions of the house, from fashion’s phantasmagoric self-representations. This is likely the source of Epilogue’s referentiality. Michele’s program is one of originality without invention. As much, it is about pastiche and super-position. Hence, the frequent appearance of reference images, which appear to be as important to the “show” as the looks themselves. In this, we can detect some other clear influences, from the same 1970s New York milieu that embraced the visual repertoire of roughness. The gleeful celebration of the half-baked and the dull—hours of footage of “the makeup chair, the lighting rig and outside security”—is clearly Warhol. Specifically, it recalls his 1964 8-hour-plus stationary film of the Empire State Building. The influences of the Factory can also be felt in the overt fetishism of the camera, and the attempted exposure of commercial myth-making via its own devices. As in avant-garde theatre, Epilogue’s show takes place backstage. This revelation does not make the artifice any less powerful. What is interesting is Michele’s suggestion that a ruthless transparency, a brutal light shone into the excesses of fashion’s own faded glamour, is a route forward from a crisis that looks to become endemic. There is no redemption offered here—Michele is too knowing to push such sentimentality. But there is honesty. This raises many questions. Not least, we might ask whether this form of irony has the power to put high-commercial design retail onto a new footing. The techniques of Epilogue are new to fashion, but they are not new. Such techniques, in art and architecture, have often led not to a renaissance but to a morass of sterile self-contemplation. Pop-bricolage, auto-exposure, and anti-charisma form but one arsenal of techniques to reposition the industry in a new climate. This is rather different from the more participatory and activist approach of scandal-hit Dolce & Gabbana—who mounted a show at Humanitas University (note the name) where they have been funding coronavirus research. In fact, both are necessary. The industry will need to find new routes through design and aesthetic politics, as well as to its business practices and relations with a broader world. Michele has understood that the fairytale must end and is perhaps one of the few designers to propose a compelling alternative.