Opening his eyes, Shiroe found himself surrounded by the quiet, luscious green, accompanied by the smell of moisture in the air, the bright sunlight and clear blue skies. This however, was no post-COVID travel to a dream destination. He soon found everything around him—ruins of nearby buildings, stationery cars and roads—to be wrapped or submerged in that same green. Overlooking the city from atop the ruins of a nearby building, surprise and shock gripped Shiroe as he saw the magnificent Silverleaf Tree of Akihabara, and more so, when a “status screen” appeared in front of him. With no option to log out, he quickly looked at his “Friends list” on the screen. Relieved to be able to contact his friend, Naotsugu, he runs to meet him near the Silverleaf Tree.

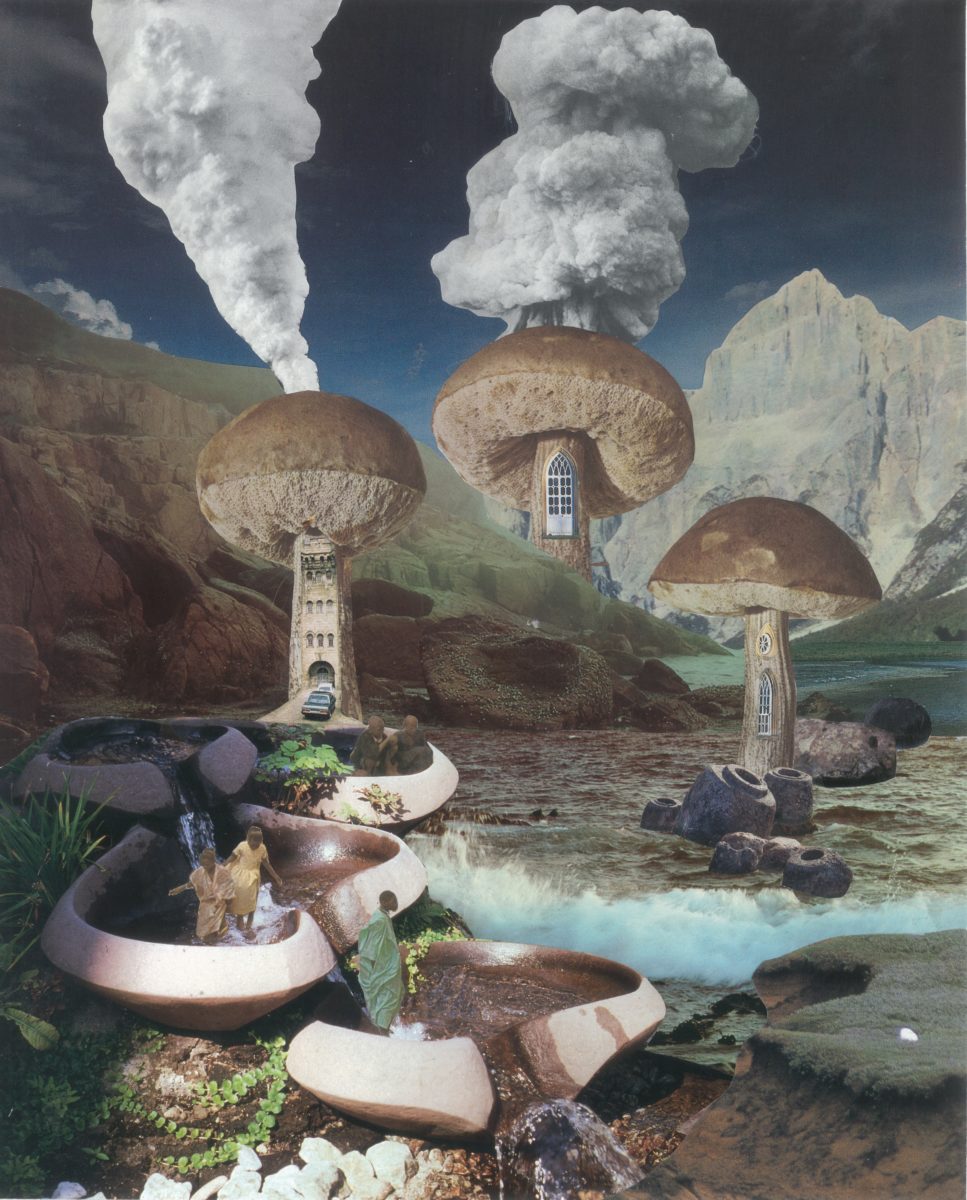

In the midst of idyllic lakes, greens and ruins, they touched, felt and smelled their surroundings, surmising that they were in their MMORPG world of Elder Tale, not as remote gamers, but in-person and donning their in-game avatars. Shiro (an Enchanter) and Naotsugu (from the “Guardian” class) soon learnt that they, together with 30,000 Japanese gamers who were logged in at the time of an expansion pack update, had suddenly been transported to, and were now stuck in Elder Tale. Together with another acquaintance, Akatsuki (from the “Assassin” class), they team up and find new friends from across different classes, ages, shapes and sizes along the way. They also formed a guild called Log Horizon, so as to face this world, which is for now, their new yet familiar reality.

The above is the plot of a Japanese manga and anime series titled Log Horizon. I’ve grown to be fascinated by this genre, which refers to fictional Japanese manga/anime known as isekai, meaning a different, strange and queer world. A typical storyline of would often involve protagonists who are otaku—a pejorative term referring to die-hard nerds being fanatical about popular culture and its attendant products. These protagonists often find themselves suddenly and unwillingly transported to this new world.

There are also significant isekai stories that depict gamers finding themselves unable to extricate or log out from an MMORPG game they have been involved in for a significant period of time, with no knowledge of what has happened to their bodies in real life revealed to the protagonist or audience. The story then follows their endeavours of learning to survive, flourish and belong through establishing friendships and solidarities in a place filled with magic and creatures, using their wit and knowledge from their previous worlds.

While sitcoms such as Big Bang Theory and Silicon Valley also depict nerds, they are categorically deemed as smart and productive for society, albeit socially awkward. Otaku protagonists in isekai stories however, are usually from the hikikomori communities, better known as “shut-ins.” In Japan, hikikomoris are commonly associated with males (even though one in three are females), ranging from their teens to their thirties, who withdraw from social activities, and often cease communicating with their families face-to-face over prolonged periods. Hikikomoris have also come to be widely understood as a condition or state of being, rather than a psychiatric or medical issue, as well as becoming a symbol (or caricature) of sorts that represent a generation of deviant, selfish and parasitic youths unwilling or unable to mature into economically independent adults and useful citizens of Japan. Their situation and presence have also been attributed to poor parenting and a lack of economic and social support structures.

My fascination with the isekai stories is the willingness and abilities of these hikikomoris to participate in another world, take up responsibilities and missions (inlife-or-death situations) either with existing friends or gradually through new friendships. In Log Horizon, some protagonists are subsequently revealed to be hikikomoris, struggling to meet the “grown-up” expectations in their original worlds. Yet in the new but familiar Akihabara in Elder Tale, they initiate to form a Round Table Alliance. These gamers soon realise facing new realities within this world entails more than the typical gaming activities, such as battling monster bosses and magical quests. Rather, as adventurers with magic and might in this world, they take on a superior leadership role and now have to collaborate, negotiating political and social realities (including inequalities) through extensive and thoughtful strategic thinking and action.

"My fascination with the isekai stories is the willingness and abilities of these hikikomoris to participate in another world, take up responsibilities and missions (inlife-or-death situations) either with existing friends or gradually through new friendships."

In the midst of living in the new, strange world, Shiroe and friends had to confront and rethink some of their old world assumptions and relations. One such instance was the gamers’ daily interactions with Elder Land’s non-playable characters (background characters with fixed scripts and functions in games), envisioning shared futures with them, including negotiations for equitable distribution of resources and abilities.

The question perhaps is why their reluctance and difficulty to partake in their original reality transforms into a drive to survive and win, to become sociable and fulfil common tasks, or better yet, become significant figures in this new world. There are also occasions where protagonists rely on past “real” world experience revealing that they have been observant, and not as self-absorbed and clueless as one would expect of a hikikomori All these challenges are meted out with the possibility that dying on a quest may mean a true death with no reset or try again.

If hikikomoris and otakus have often been described as escaping from the real world as an easy and lazy cop out, then what are they running from? What could the isekai genre illuminate about protagonists who are understood as trapped yet are able to find a freedom to invest themselves in? What kind of futures did they envision to allow such a turnaround in this strangely familiar world?

The hikikomori phenomenon was understood to have materialised alongside the emergence of a new middle-class in postwar Japan. This shaped the population with its seductive narrative of a successful life with appropriate aspirations, goals and values, disseminated through social institutions such as family, school, and work. This narrative has been thwarted by economic crises and shrinking incomes that have cast doubts on the structurally deterministic relationship between a successful path and stable future. Against this backdrop, hikikomori could be seen as a reflection of exhaustion among the youths, manifesting in escapes’ towards “deviant” consumption patterns.

If I think of paths as lines oriented towards expected destinations alongside Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology and her description of lines as “a way of life”, the assumption promises that following specific lines leads to designated destinations in the future, reaching certain points along life’s course. This also means that as one moves through a chosen line, they lose sight of the other lines as they diverge along different paths. Deviance then, is the act of departing from these well-trodden paths; bodies unwilling or unable to follow the lines assumed to lead to ‘good’ futures.

Intricately entwined to futures is the notion of hope, and its attendant questions—how could hope be otherwise understood today, and how does one sustain and keep hope alive, for a future that cannot possibly be known? Here, I find anthropologist Hirokazu Miyazaki’s notion of hope refreshing. For him, hope is understood not as an emotional state of positive feeling about the future, nor a religious sense of expectation but characterised as a cognitive process through which the subject adapts available principles and skills so as to respond to adversity. This process of hope thus requires a “reorientation of knowledge” towards the future, as well as continuous processes of imaginations, discussions and persistent considerations of how problems might be surmounted and differences resolved. In this sense, we can also characterise the refusal of these attempts as hopelessness.

"Hope is understood not as an emotional state of positive feeling about the future, nor a religious sense of expectation but characterised as a cognitive process through which the subject adapts available principles and skills so as to respond to adversity."

Thinking about hikikomoris in the isekai stories then, one could perhaps read their inability or hopelessness as a refusal to travel down the lines and paths of the “real” world that most of us deem as natural. At the same time, it also lends plausibility to consider how they perceive the isekai life as holding more potential for hope. Hikikomoris in their “deviance” and loneliness, “escape” into a strange world to search for different forms of sociality. Ahmed describes how “deviants” tend towards others who are alike insofar as they also “pervert” lines of desire. Moving sideways and off the straight line, they come into contact with different bodies and worlds only to find new-old friends. In other words, such contacts in a new, queer world require following different lines of connections, associations, knowledges and desires.

Log Horizon expresses this through the various quests gamers embark on, and also demonstrates their cognitive commitments towards hope. This is seen in their willingness to respond to adversity through creative and shrewd planning, learning from failures, and gaining new knowledge and perspectives from the People of the Land, and surmounting problems together.

The isekai hence is more than just a world where humans, magical beasts and demons roam and live together with fluid sexualities, or one where those who face disabilities can now run and explore new places. In their old world where an emphasis on “strong” and “productive” citizens meant creating “winners” and “losers” such as the hikikomoris, the implication was that future and hope were unevenly distributed and in close proximity with ‘winners’.

If lines are a way of life that become paths leading to certain futures, Ahmed highlights how it also holds a paradox: lines are both created by being followed, and are followed by being created. Now free from the thick, deep and well-trodden paths, Elder Tale functions as that new yet familiar world holding hospitable space for speculative potentialities. We cheer on Shiroe and his friends as they create new lines that expand horizons, including working toward changing the rules of the world of Elder Tale. The grounds of Elder Tale after all, is big and wide enough for more than one line and path, and expansive and queer enough to allow curvy detours and turns.